Black Coffee (play)

| Black Coffee | |

|---|---|

| |

| Written by | Agatha Christie |

| Date premiered | 8 December 1930 |

| Place premiered | United Kingdom |

| Original language | English |

Black Coffee is a play by the British crime-fiction author Agatha Christie which was produced initially in 1930. The first piece that Christie wrote for the stage, it launched a successful second career for her as a playwright. In the play, a scientist discovers that someone in his household has stolen the formula for an explosive. The scientist calls Hercule Poirot to investigate, but is murdered just as Poirot arrives with Hastings and Inspector Japp.

The successful play was adapted as a film in 1931. In 1998, 22 years after Christie's death, it was re-published in the United Kingdom and the United States in the form of a novel. The novelisation was undertaken by the Australian writer and classical music critic Charles Osborne, with the endorsement of the Christie estate.

Writing and production

[edit]Agatha Christie began writing Black Coffee in 1929, feeling disappointed with the portrayal of Hercule Poirot in the previous year's play Alibi, and being equally dissatisfied with the motion-picture adaptations of her short story The Coming of Mr. Quin and her novel The Secret Adversary as The Passing of Mr. Quin and Die Abenteurer GmbH.[1] According to the foreword to the current HarperCollins edition of Black Coffee in its novelised form, she finished writing the play in late 1929.

She mentions Black Coffee in her 1977 life story, Autobiography, describing it as "a conventional spy thriller ... full of cliches, it was, I think, not at all bad".[2] Nonetheless, her literary agents had advised her to forget the play entirely and she was willing to do so until a friend connected with the theatre suggested that it might be worth producing.

Christie wrote in her autobiography that the debut performance of Black Coffee took place at the Everyman Theatre in Hampstead. However, no record exists of such a staging and she was undoubtedly confusing it with the true opening production at the Embassy Theatre in Swiss Cottage (now London's Central School of Speech and Drama) on 8 December 1930.[3] The production ran in that theatre only until 20 December. On 9 April 1931 it re-opened at the St Martin's Theatre (later to be the second home of Christie's most enduring stage work The Mousetrap), where it ran until 1 May before transferring to the Wimbledon Theatre on 4 May. It then went to the Little Theatre on 11 May, finally closing there on 13 June 1931.

Poirot was played initially by the well-known character actor Francis L. Sullivan who became a good friend of the author. She approved of his portrayal despite the fact that physically he was far too tall for the dapper little Belgian detective. (Sullivan stood six feet, two inches in height.)[4] Also in the premiere cast was (Sir) Donald Wolfit, playing Dr. Carelli. Wolfit would become renowned in England as an actor-manager, best remembered for his vivid interpretations of Shakespearean roles and other big-scale classical parts. John Boxer played Captain Hastings and Richard Fisher Inspector Japp.[5]

Unlike most other Christie plays, Black Coffee did not transfer to the New York stage.[6]

Plot

[edit]

Scientist Sir Claud Amory is developing a formula for a new type of atomic explosive. He discovers that the formula has been stolen from his safe and rings Hercule Poirot asking for his help. While waiting for Poirot to arrive, Amory gathers the members of his household: his sister Caroline, his niece Barbara, his son Richard, Richard's Italian wife Lucia, his secretary Edward Raynor, and Lucia's old friend Dr. Carelli. As Lucia serves black coffee, Amory locks them in the house and offers a deal: after one minute, the lights will go off. Whoever stole the envelope containing the papers should put it on the table, following which no questions will be asked. If the papers are not there, Amory will pursue and prosecute the thief.

After the lights return, everyone is pleasantly surprised to see the envelope on the table. Poirot arrives and Richard tells him that the matter is resolved. However, Sir Claud is found dead in his chair and the envelope is empty. Lucia implores Poirot to investigate, but Richard reminds her that his father commented on the bitter taste of the coffee she had served him. Poirot surmises that Sir Claud's coffee was poisoned with hyoscine, which is confirmed by the family doctor. As Poirot starts interrogating the family members, he establishes that Sir Claud had already been poisoned when he had everybody locked in the room.

Poirot finds a duplicate key to the safe and some letters written to Sir Claud telling him to stay away from "the child of Selma Goetz." Poirot discovers that this child is Lucia, whose mother Selma Goetz was an international spy. Lucia confesses that Carelli was blackmailing her. He wanted her to steal the documents and made the duplicate key for this purpose. She claims that she stole hyoscine for herself, intending to commit suicide before Richard found out her secret. In a fit of hysteria, she admits to murdering Sir Claud. Richard claims that she is taking his blame on her. Poirot reveals that neither of them is guilty.

Once alone with Hastings and Inspector Japp, Poirot explains that when the lights went off, Lucia threw away the duplicate key. Poirot finds the formula, torn into pieces and hidden in a vase. Poirot sends Hastings and Inspector Japp on some errands. Poirot complains that he feels famished due to the heat. Raynor serves them both whisky. Poirot accuses Raynor of the theft and murder. Raynor mockingly accepts the accusations, but Poirot has difficulty talking or listening to him. Raynor tells him that his whisky has been poisoned as well. Once Poirot passes out, Raynor retrieves the formula and puts it back in the envelope. As he turns to escape, he is apprehended by Hastings and Japp. Poirot surprises him by getting up, revealing that he exchanged his poisoned cup for another one with the help of Hastings. After Raynor is arrested, Poirot leaves the place, but not before reuniting Richard and Lucia.

Reception

[edit]The Times reviewed the work in its issue of 9 December 1930, saying that, "Mrs Christie steers her play with much dexterity; yet there are times when it is perilously near the doldrums. Always it is saved by Hercule Poirot, the great French [sic] detective, who theorizes with the gusto of a man for whom the visible world hardly exists. He carries us with him, for he does not take himself too seriously, and he salts his shrewdness with wit. For a ruthless investigator he is an arrant sentimentalist; but that is one of the ways in which Mrs Christie prevents her problem from becoming tedious. Mr Sullivan is obviously very happy in the part, and his contribution to the evening's entertainment is a considerable one. Mr Boxer Watsonizes pleasantly, and Miss Joyce Bland, as a young lady who must wait until the very end before knowing a moment's happiness, contrives to excite our sympathy for her distress. The remainder of the cast is rather serviceable than exciting.[7]"

The Observer's issue of 14 December 1930 contained a review by "HH" in which he concluded that, "Miss Agatha Christie is a competent craftsman, and her play, which is methodically planned and well carried out and played, agreeably entertains."[8]

The Guardian reviewed the play in its issue of 10 April 1931. The reviewer stated that, "Miss Christie knows the ropes, keeps to the track, sets her Herculean protector in defence of innocence, and unmasks the real villain at eleven o’clock. One must be something of a ritualist to find enchantment in such matters. Mr. Francis Sullivan makes a large, guttural, amiable sleuth of the sagacious Hercules [sic]. He is wise not to imitate Mr. Charles Laughton who gave us such a brilliant study of the Belgian some time ago. He makes his own portrait and does it with a competent hand." The reviewer praised others in the cast by name and concluded, "the company conduct themselves with a proper sense of the ceremonial involved in a detective play. But it is surely permissible to be surprised that adult people can be found in fairly large numbers to sit undismayed through the execution of such ritual as this."[9]

Two days later, Ivor Brown reviewed this second production in The Observer when he said that, "If you are one of those playgoers who are eternally excited by a corpse in the library and cross-examination of the family, all is well. If not, not. To me the progress of detection seemed rather heavy going, but I start with some antipathy to murdered scientists and their coveted formulae. Black coffee is supposed to be a strong stimulant and powerful enemy of sleep. I found the title optimistic. "[10]

The Times reviewed the play again when it opened at the Little Theatre in its issue of 13 May 1931. This time it said that, "Its false scents are made for the triumph of the omniscient Belgian detective, complete according to the best tradition with unintelligent foil; and if they appear sometimes to be manufactured with a little too much determination and to be revived when they seem most likely to be dissipated, they may be allowed because they just succeed in maintaining our sympathy with distressed beauty and our interest in the solution of a problem. Though much of the dialogue is stilted, the complacent detective has an engaging manner.[11]"

Credits of London production

[edit]The director was André van Gyseghem.

- Francis L. Sullivan as Hercule Poirot

- Donald Wolfit as Dr. Carelli

- Josephine Middleton as Miss Caroline Amory

- Joyce Bland as Lucia Amory

- Lawrence Hardman as Richard Amory

- Judith Menteath as Barbara Amory

- André van Gyseghem as Edward Raynor

- Wallace Evennett as Sir Claud Amory

- John Boxer as Captain Arthur Hastings

- Richard Fisher as Inspector Japp

Cast of 1931 production

[edit]- Francis L. Sullivan as Hercule Poirot

- Josephine Middleton as Miss Caroline Amory

- Dino Galvani as Dr. Carelli

- Jane Milligan as Lucia Amory

- Randolph McLeod as Richard Amory

- Renee Gadd as Barbara Amory

- Walter Fitzgerald as Edward Raynor

- E. Vivian Reynolds as Sir Claud Amory

- Roland Culver as Captain Arthur Hastings

- Neville Brook as Inspector Japp

Adaptations

[edit]

1931 film

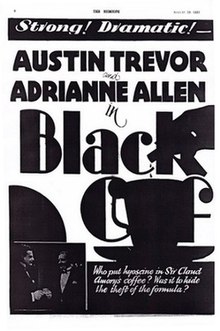

[edit]The play was adapted into a motion picture, also entitled Black Coffee, in 1931, with Austin Trevor in the role of Poirot. Running to 78 minutes, the motion picture was produced by Julius S. Hagan and released on 19 August 1931 by Twickenham Film Studios. This was one of three appearances that Trevor made as Poirot, having also appeared in Alibi (1931) and Lord Edgware Dies (1934). It is now considered a lost film.[13][14]

Novel

[edit]Like The Unexpected Guest (1999) and Spider's Web, the script of the play was turned into a novel by Charles Osborne. The novelisation was copyrighted in 1997 and published in 1998. Kirkus Reviews called it "pleasantly serviceable" with a "suitably genteel" atmosphere.[15] Publishers Weekly deemed it a "welcome addition to the Christie canon."[16]

References

[edit]- ^ Morgan, Janet. Agatha Christie, A Biography. (Page 177) Collins, 1984 ISBN 0-00-216330-6

- ^ Christie, Agatha. An Autobiography. (Pages 433 -434). Collins, 1977. ISBN 0-00-216012-9

- ^ Agatha Christie – Official Centenary Celebration (Page 78). 1990. Belgrave Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-00-637675-4.

- ^ Book and Magazine Collector. Issue 174. September 1998

- ^ Lachman, Marvin (2014). The villainous stage : crime plays on Broadway and in the West End. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9534-4. OCLC 903807427.

- ^ Haining, Peter. Agatha Christie – Murder in Four Acts (Page 26). 1990. Virgin Books. ISBN 1-85227-273-2.

- ^ The Times 9 December 1930 (Page 12)

- ^ The Observer 14 December 1930 (Page 18)

- ^ The Guardian 10 April 1931 (Page 11)

- ^ The Observer 12 April 1931 (Page 15)

- ^ The Times 13 May 1931 (Page 13)

- ^ Official Centenary Celebration (Page 78)

- ^ Aldridge, Mark (2016). Agatha Christie on Screen. Springer.

- ^ Sanders, Dennis (1989). The Agatha Christie companion : the complete guide to Agatha Christie's life and work. Len Lovallo. New York: Berkley Books. ISBN 0-425-11845-2. OCLC 20660363.

- ^ BLACK COFFEE | Kirkus Reviews.

- ^ "Black Coffee by Charles Osborne, Agatha Christie". www.publishersweekly.com. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

External links

[edit]- Black Coffee at the official Agatha Christie website

- Black Coffee (1931) at IMDb

- Le Coffret de Laque (1932) at IMDb