Austro-Hungarian fortifications on the Italian border

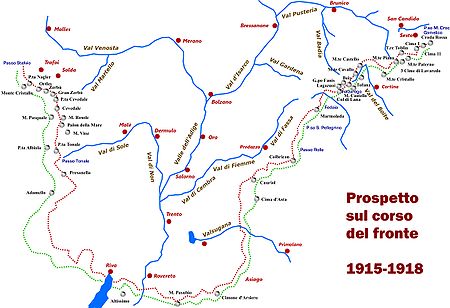

The Austro-Hungarian fortifications on the Italian border were constructed in the 19th and early 20th centuries to protect against invasion from Italy. Most were built in what is today the Trentino-Alto Adige region; some built outside this territory were ceded to Italy after 1866. By the First World War many of them were obsolete, but nevertheless played a role in deterring and containing Italian assaults.[1][2]

Terminology

[edit]Generally, in Austrian military terminology these defensive structures were not referred to as forts. The terms used to describe them were werk ('works'), sperre ('barrier') or straßensperre ('roadblock'). Defence districts were referred to as 'rayons'. Originally there were only two, divided into subrayons or sections. Over the course of the First World War, however, more and more subrayons and sections were replaced by rayons.

Construction

[edit]Before 1866

[edit]Before the Second Italian War of Independence the main Austrian fortifications in Italy were the Quadrilatero in the Po valley.[3] In addition to these strongpoints the Franzensfeste Fortress (1833-1838) was built to guard the southern approaches to the Brenner Pass[4] and the Nauders road barrier (1838–40) to guard the Reschen Pass.[5][6] Doss Trento was also fortified from 1848 to 1859.[7]

After 1859, the most important passes along the new border with Italy between Lake Garda and Switzerland were fortified, as was Riva del Garda and the road to Trento. These fortifications mostly consisted of large multi-storey structures of natural stone, with cannon mounted behind embrasures. The introduction of rifled firearms soon rendered their design obsolete, but they provided shelter for the guns, which was important in a mountain environment. It was also assumed that the Italians would not try to manoeuvre heavy artillery up into the mountains to threaten these installations. Among the structures dating from this period were de:Forte Ceraino, de:Forte Rivoli and de:Forte Monte, but these were built in territory that passed to Italy in 1866.[8][9]

1866-1900

[edit]

After the Third Italian War of Independence Austria also fortified the new eastern border with the Veneto. From 1870 to 1873 a group of defensive works was erected at Civezzano to block the route to Trento from the Brenta valley. From 1878 to 1883 the defences of Trento itself were expanded in what became known as the Trientiner style, using a light and economical construction method, with most guns placed in open batteries. A Gruson gun turret was built at the San Rocco works.[10][11] Defences were also upgraded at Fort Hensel, built between 1881 and 1890, which blocked the it:Val Canale near Malborgeth on the southern border of Carinthia[12][13] and the Kluže Fortress further east in present-day Slovenia.

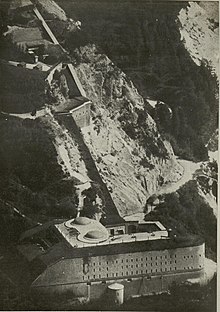

From 1884 onwards, many new defences were built according to a relatively uniform scheme overseen by Field Marshal Julius Ritter von Vogl.[14] In particular, the passes in the Dolomites and the Brenta were fortified for the first time, as was the Predil Pass in modern Slovenia. Lardaro was reinforced with the new Corno works;[15] the defences of Trento were expanded with the Romagnano and Mattarello works[16] and the Riva fortress was reinforced with the new batteria di mezzo.[17] The Vogl works were compact integrated structures combining armament and accommodation in a single block. They were mostly built of concrete, with the front clad with granite blocks. The armament consisted of mostly three or four 12-cm cannons behind armoured embrasures, and two to four 15-cm mortars in armored rotating domes on the roof.[18] The works were surrounded by a ditch that could be swept by fire from several caponiers. For close defense, 11 mm mitrailleuses were initially used and machine guns installed from 1893. Because of their embrasures and being built several stories high they had a marked elevation above ground.

1900-1915

[edit]

In the years before the First World War, the Riva fortress was strengthened with the Garda and Tombio works and Ladaro with the Carriola work. The Tonale Pass, previously fortified with only one old works, was expanded into a cluster of fortifications with five works of different sizes while Folgaria and Lavarone southeast of Trento were also expanded and strengthened.[19]

Developments in the technology of artillery led to new design parameters for fortifications, able to withstand increased calibre and penetration of modem shells. Increasingly, structures were built underground. 10-cm howitzers in rotating armored domes were now standard, together with machine guns for replacing both can in embrasures and machine guns close defense. Typical of this design was the works at Valmorbia, unfinished when Italy declared war in May 1915.[20]

Rayon of Tyrol

[edit]The Rayon of Tyrol Came under the Tyrol State Defense Command:

Subrayon I

[edit]Border section 1 - Stilfserjoch Barrier: Ortler with the Gomagoi (1860–62) roadblock protecting the road from the Stelvio Pass to the Vinschgau and the Reschen Pass and Nauders roadblock (1838-1840) blocking the Inn Valley to the north and the road to Landeck and Vorarlberg.[21]

Subrayon II

[edit]Border section 2 - Tonale Barrier: barriers guarding the Tonale Pass. Strino (1860-1862), Tonale (1907–10), Presanella (1910–12) Pejo (1908-1910) and Mero (1905-1910/12). The role of these works was to block the Tonale pass road and to protect the Sulztal (Val di Sole) and the Adige valley, preventing Trento from being cut off from the north.[22][23]

Subrayon III

[edit]

Border section 3 - Lardaro Barrier: south of the Adamello-Presanella group, Larino (1860-1861), Danzolino (1860 to 1862), Corno (1890 to 1894), Revegler (1860-1862) and Carriola (1911-1915). The Lardaro lock secured the Giudicarie to the north and the confluence of the Valdaone to the east. This covered the rear of the Riva fortress and the flank of Trento.[24][25][26]

Border section 3 - the Riva Fortress securing the roads around Lago d'Ampola and Lago di Ledro to Trento and the Adige Valley. Riva had the following structures:

- San Nicolo Battery (1860-1862)

- Monte Brione middle battery (1898-1900)

- Monte Brione North Battery (1860-1862, 1911–1915)

- Nago road block (1860-1862)

- Garda (1905 to 1909)

Blocking group Ponale consisted of:

- Ponale roadblock (1904-1918)

- Bellavista battery (1909)

- Ponale defensive wall

- Tombio outer works (1907-1910)

Border section 4 - The Fortress of Trento and the Adige Barrier (Etschtalsperre), countering threats from the south (Adige Valley) and southeast from the Valsugana.

Fortress of Trento major structures:

- Buco di Vela road block (1860-1862)

- Doss di Sponde battery (1860-1862)

- Mattarello (1897-1900)

- Candrai (1879-1882)

- Mandolin

- Casara (1880-1881)

- Martignano (1878-1880)

- Civezzano (1870-1873)

- Celva (1915)

- Cimirlo (1881-1882)

- Roncogno (1880-1882)

- San Rocco (1880-1884, 1902)

- Brussa ferro (1881-1882)

- Doss Fornas (1882-1883)

- Romagnano (1892-1915)

There were also many smaller works, armored machine-gun positions and concrete infantry strongpoints.

The Val di Non barrier consisted of the large Rocchetta roadblock (1860–64)[27] securing Mezzolombardo (Welschmetz) in the Non Valley against the Val di Sole if a breakthrough over the Tonale Pass succeeded.

The Adige-Arsa Barrier consisted only of the unfinished Valmorbia works (1912-1915, also referred to as "Forte Pozzacchio") in Vallarsa. Further projects (Mattassone/Coni Zugna/Pasubio/Cornale and Vignola) did not get beyond the planning phase.[28]

Border section 5 - Folgaria/Lavarone/Sette Comuni built between 1907 and 1913 and among the most modern fortresses in Austria-Hungary. It was in front of the line of the older works (Tenna, Colle delle benne, Mattarello and Romagnano) from the Vogl construction period.

Lavarone Group (Lafraun):

- Gschwent (Italian: Forte Belvedere, 1909–1912)

- Lusern (Italian: Campo di Luserna, 1907–1910)

- Verle (Italian: Forte di Busa di Verle, 1907–1911)

- Vezzena 1907–1912)

Folgaria Group (Vielgereuth):

- Serrada (Italian: Dosso del Sommo, 1912–1915)

- Sommo (Italian: Sommo alto, 1912–1915)

- Sebastiano (also Cherle, 1909–1913)

Border section 6 - Valsugana - external works at Caldonazzo and Levico:

- Tenna (1884)

- Colle delle benne (1884)

- Busa Grande (1915)

Subrayon IV

[edit]Border section 7 - Kreuzberg Pass to Lusia Pass (Fiemme Valley)

Border section 8 - Lusia Pass to Monte Mesola. The Rolle Pass barrier consisted of the Paneveggio barrier, Dossaccio (1889-1892, 1912) and Albuso (1889-1892, 1912) blocking the Rolle Pass, the Travognolo Valley and the route from Fassa to the Fiemme Valley. Further back in the Pellegrino valley was the Moena barrier (1897-1899).

Subrayon V

[edit]Border section 9 - Monte Mesola to Gottrestal.

The Buchensteintal Barrier consisted only of the la Corte (1897-1900) and the Ruaz road barrier (1897-1900). They blocked the way from Alleghe to Canazei and the Pordoi Pass to Corvara.

Valparola Pass Barrier The Tre Sassi barrage (1897-1900) blocked access to the Val Badia.

Ampezzo Blocking Group consisting of Plätzwiese (1889-1894) securing the Stolla Valley and the Höhlensteintal as well as the Landro (1884-1892), securing the road from Cortina d'Ampezzo to Toblach and the Puster Valley.[29][30]

Border section 10 - Gottrestal to the Carinthian border with the Sexten Barrier. Haideck (1884-1889) and Mitterberg (1884-1889) secured Sexten and the Kreuzberg Saddle.[31][32]

Rayon of Carinthia

[edit]In the Rayon of Carinthia, the subrayons were called sections. In 1915 he was under the command of Franz Rohr von Denta. The border from Krn to the Mediterranean Sea was not fortified and therefore not included in this scheme.

Section I

[edit]Kreuzberg Pass - Plöcken Pass - Stranigerspitze/Monte Cordin

Section II

[edit]Straningerspitze/Monte Cordin - Naßfeld Pass - Shinouz/it:Monte Scinauz

The Malborgeth Barrier consisted only of Fort Hensel "A" (1881-1884) and "B" (1881 to 1890) near the village of Malborgeth in the Canale Valley. They blocked the road from Pontafel to Tarvis and Villach in Carinthia. "Fort Hensel" was not referred to as a work, but as a fort because it was named after a person and not, as was more common, after a location. It was named after Captain it:Friedrich Hensel, who fell here in 1809 in the war against Napoleon.[33]

Section III

[edit]

Shinouz/it:Monte Scinauz- Predil Pass - Rombon

In the Seebachtal, the Predil / Battery Predilsattel (1897 to 1899) and Raibl (1885 to 1887, also called Seewerk Raibl, Raiblsee or Seebachtalsperre bei Raibl ) works blocked access through the Seebachtal and the Predilpass to Carinthia. Shortly after the factory directly on the Predilpass, there was also the Oberbreth / Predil depot (1850) on the Krainer side.

Section IV

[edit]Rombon - Krn

Fort Hermann (1897-1900) and Flitscher Klause (1880-1882) above Bovec (Flitsch) (in modern Slovenia) prevented a breakthrough into Austria from the Isonzo valley via the Predil Pass. Unusually "Fort Hermann" was not referred to as a works but as a fort. It was named after captain de:Johann Hermann von Hermannsdorf, who fell here in 1809 in the war against Napoleon.[34][35][36]

See also

[edit]- Italian fortifications on the Austro-Hungarian border

- Mines on the Italian front (World War I)

- Séré de Rivières system

- Viktor Dankl von Krasnik

- Alpine Wall

References

[edit]- ^ Ivan Bruno Zabeo (2016). Dolesi al fronte. La prima guerra mondiale. Mazzanti Libri - Me Publisher. p. 41. ISBN 978-88-98109-85-2. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ Alexander Jordan (2008). Krieg um die Alpen: Der Erste Weltkrieg im Alpenraum und der bayerische Grenzschutz in Tirol. Duncker & Humblot. pp. 272–3. ISBN 978-3-428-52843-1. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ Geoffrey Wawro (1997-09-13). The Austro-Prussian War: Austria's War with Prussia and Italy in 1866. Cambridge University Press. pp. 89–. ISBN 978-0-521-62951-5. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "Franzensfeste Fortress". museums-southtyrol.it. Museums of South Tyrol. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "Festung Nauders". nauders.tirol.gv.at. Gemeinde Nauders. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Oswald von Gschliesser (1965). Tirol---Österreich: gesammelte Aufsätze zu deren Geschichte. Wagner. p. 133. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Riccardo Gasperi (1968). Per Trento e Trieste l'amara prova del 1866: Storia politico-militare del 1866, con particolare riguardo alla spedizione Medici nella Valsugana. Comitato provinciale per il cinquantenario dell'unione del Trentino all'Italia. p. 19.

- ^ Ferdinand Mayer (1875). Geschichte des k.k. [i.e. kaiserlich-koeniglichen] Infanterie-Regimentes Nr.39. Рипол Классик. p. 548. ISBN 978-5-87706-982-4. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Arthur Janke (1874). Reise-Erinnerungen aus Italien, Griechenland und dem Orient: Mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der militairischen Verhältnisse. Schneider. p. 29. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "Forte San Rocco a Trento: segnalazione per la Lista Rossa". italianostra.org. Italia Nostra. Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "San Rocco". fortificazione.net. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Weiss, Ulrike. Il Forte Hensel a Malborghetto 1881-1916. Fortress Books.

- ^ "Fort Hensel". kick-fortification. Österreichische Gesellschaft für Festungsforschung. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Rassegna storica del Risorgimento: organo della Società nazionale per la storia del Risorgimento italiano. S. Lapi. 2008. p. 6. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ "Werk Corno". trentinograndeguerra.it. Museo Storico Italiano della Guerra. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "Hauptwerk Mattarello". kuk-fortification.net. Österreichische Gesellschaft für Festungsforschung. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "Mittelbatterie Riva". trentinograndeguerra.it. Museo Storico Italiano della Guerra. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "15 cm Panzermörser". kuk-fortification.net. Österreichische Gesellschaft für Festungsforschung. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "Beschreibung der / Description of the Sperre Folgaria – Lavarone". kuk-fortification.net. Österreichische Gesellschaft für Festungsforschung. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ "Werk Valmorbia". kuk-fortification.net. Österreichische Gesellschaft für Festungsforschung. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ Südtiroler Schützenbund (2005). Tirol vor und im 1. Weltkrieg: der Erste Weltkrieg 1914-1918, die Tiroler Front 1915-1918. Arkadia. p. 165. ISBN 978-88-8300-029-4. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "On the Paths of the Great War". pontedilegnotonale.it. Consorzio Pontedilegno-Tonale. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "Saccarana". fortificazione.net. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Heinz von Lichem (1980). Gebirgskrieg 1915-1918: Ortler, Adamello, Gardasee. Athesia. pp. 297–8. ISBN 978-88-7014-175-7. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "Werk Danzolino". kuk-fortification.net. Österreichische Gesellschaft für Festungsforschung. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ "Straßensperre Revegler". kuk-fortification.net. Österreichische Gesellschaft für Festungsforschung. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Marco Milanese (2020-07-31). APM – Archeologia Postmedievale, 22, 2018. L'archeologia della Prima Guerra Mondiale. Scenari, progetti, ricerche / The archaeology of the First World War. Research background, projects and case studies. All'Insegna del Giglio. pp. 107–. ISBN 978-88-7814-959-5. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "Werk Valmorbia". kuk-fortification.net. Österreichische Gesellschaft für Festungsforschung. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ "Werk Plätzwiese". kuk-fortification.net. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ "Werk Landro". kuk-fortification.net. Österreichische Gesellschaft für Festungsforschung. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ "Werk Haideck". kuk-fortification.net. Österreichische Gesellschaft für Festungsforschung. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ "Werk Mitterberg". kuk-fortification.net. Österreichische Gesellschaft für Festungsforschung. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ "Fort Hensel". kuk-fortification.net. Österreichische Gesellschaft für Festungsforschung. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Jahrbuch der Kaiserlich-Koniglichen Geologischen Reichsanstalt. Aus der K. K. Hof-und Staats-Druckerei. 1858. p. 357. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Franz Bersin (1875). Laibacher Schulzeitung. Organ des krainischen Landes-Lehrervereins. Red. Joh(ann) Sima. Kleinmayr & Bamberg. p. 229. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ "Fortification Fort Hermann". potmiru.si. Ustanova »Fundacija Poti miru v Posočju«. Retrieved 16 October 2020.