Anti-Armenian sentiment in Turkey

Anti-Armenian sentiment or Armenophobia in Turkey has a long history dating back to the Ottoman Empire, something that eventually culminated in the Armenian genocide. Today, anti-Armenian sentiment is widespread in Turkish society. In a 2011 survey in Turkey, 73.9% of respondents admitted having unfavorable views toward Armenians.[2] According to Minority Rights Group, while the government recognizes Armenians as a minority group, as used in Turkey this term denotes second-class status.[3] The word "Armenian" is widely used as an insult in Turkey by both civilians[4][5][6] and by politicians.[7][4][5]

Expressions of anti-Armenian sentiment in Turkey include discrimination and violence towards Armenians, destruction and desecration of Armenian cultural heritage in Turkey, vandalism towards Armenian churches, monuments and signs in Armenian language, and denial of the Armenian genocide. As of 2024, denial of the Armenian genocide has been the policy of every government of Turkey.

History

[edit]The presence of Armenians in Anatolia is documented since the sixth century BCE, almost two millennia before Turkish presence in the area.[8][9] The Ottoman Empire effectively treated Armenians and other non-Muslims as second-class citizens under Islamic rule, even after the nineteenth-century Tanzimat reforms intended to equalize their status.[10] Although it was possible for Armenians to achieve status and wealth in the Ottoman Empire, as a community they were never accorded more than "second-class citizen" status and were regarded as fundamentally alien to the Muslim character of Ottoman society.[11]

By the 1890s, Armenians faced forced conversions to Islam and increasing land seizures, which led a handful to join revolutionary parties such as the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF, also known as Dashnaktsutyun).[12] In 1895, revolts among the Armenian subjects of the Ottoman Empire in pursuit of equal treatment led to Sultan Abdül Hamid's decision to massacre at least 100,000 of Armenians in the state-sponsored Hamidian massacres.[13]

In 1909, the authorities failed to prevent the Adana massacre, which resulted in a series of anti-Armenian pogroms throughout the district resulting in the deaths of 20,000–30,000 Armenians.[14][15][16] The Ottoman authorities denied any responsibility for these massacres, accusing Western powers of meddling and Armenians of provocation, while presenting Muslims as the main victims and failing to punish the perpetrators.[17][18][19] These same tropes of denial would be employed later to deny the Armenian genocide.[19][20]

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) came to power in two coups in 1908 and in 1913.[21] In the meantime, the Ottoman Empire lost almost all of its European territory in the Balkan Wars; the CUP blamed Christian treachery for this defeat.[22] Hundreds of thousands of Muslim refugees fled to Anatolia as a result of the wars; many were resettled in the Armenian-populated eastern provinces and harbored resentment against Christians.[23][24] In August 1914, CUP representatives appeared at an ARF conference demanding that in the event of war with the Russian Empire, the ARF incite Russian Armenians to intervene on the Ottoman side. The ARF declined, instead declaring that Armenians should fight for the countries in which they were citizens.[25] In October 1914, the Ottoman Empire entered World War I on the side of the Central Powers.[26]

Armenian genocide

[edit]

During the Ottoman invasion of Russian and Persian territory in late 1914, Ottoman paramilitaries massacred local Armenians.[27] A few Ottoman Armenian soldiers defected to Russia—seized upon by both the CUP and later deniers as evidence of Armenian treachery—but the Armenian volunteers in the Russian army were mostly Russian Armenians.[28][29][30] Massacres turned into genocide following the catastrophic Ottoman defeat by Russia in the Battle of Sarikamish (January 1915), which was blamed on Armenian treachery. Armenian soldiers and officers were removed from their posts pursuant to a 25 February order issued by Minister of War Enver Pasha.[27][31] In the minds of the Ottoman leaders, isolated incidents of Armenian resistance were taken as evidence of a general insurrection.[32]

In mid-April, after Ottoman leaders had decided to commit genocide,[33] Armenians barricaded themselves in the eastern city of Van.[34] The defense of Van served as a pretext for anti-Armenian actions at the time and remains a crucial element in works that seek to deny or justify the genocide.[35] On 24 April, hundreds of Armenian intellectuals were arrested in Constantinople. Systematic deportation of Armenians began, given a cover of legitimacy by the 27 May deportation law. The Special Organization guarded the deportation convoys consisting mostly of women, children, and the elderly who were subject to systematic rape and massacres. Their destination was the Syrian Desert, where those who survived the death marches were left to die of starvation or disease in makeshift camps.[36] Deportation was only carried out in the areas away from active fighting; near the front lines, Armenians were massacred outright.[37] The leaders of the CUP ordered the deportations, with interior minister Talat Pasha, aware that he was sending the Armenians to their deaths, taking a leading role.[38] In a cable dated 13 July 1915, Talat stated that "the aim of the Armenian deportations is the final solution of the Armenian Question."[39]

Historians estimate that 1.5 to 2 million Armenians lived in the Ottoman Empire in 1915, of whom 800,000 to 1.2 million were deported during the genocide. In 1916, a wave of massacres targeted the surviving Armenians in Syria; by the end of the year, only 200,000 were still alive.[40] An estimated 100,000 to 200,000 women and children were integrated into Muslim families through such methods as forced marriage, adoption and conversion.[41][42] The state confiscated and redistributed property belonging to murdered or deported Armenians.[43][44]

Post-genocide

[edit]After the genocide ended, following the Turkish War of Independence and the creation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, the Turkish government enacted on 15 April 1923 the "Law of Abandoned Properties" which confiscated properties of any Armenian who was not present on their property, regardless of the circumstances of the reason. While local courts were authorized to appraise the value of any property and provide an avenue for property owners to make claims, the law prohibited the use of any power of attorney by absent property holders, preventing them from filing suit without returning to the country.[45] In addition, the defendant in the case would be the state of Turkey which had created specially tasked committees to deal with each case.[46][47]

In addition to this law, the Turkish government continued revoking the citizenship of many people with a law on 23 May 1927 which stated that "Ottoman subjects who during the War of Independence took no part in the National movement, kept out of Turkey and did not return from 24 July 1923 to the date of the publication of this law, have forfeited Turkish nationality."[48][n 1] Additionally, a further law passed on 28 May 1928 stipulated that those who had lost their citizenship would be expelled from Turkey, not allowed to return, and that their property would be confiscated by the Turkish government, and Turkish migrants would be resettled in the properties.[48]

The incident of The Twenty Classes was a policy used by the Turkish government to conscript the male non-Turkish minority population mainly consisting of Armenians, Greeks and Jews during World War II. All of the twenty classes consisted of male minority population, including the elders and mentally ill.[49] They were given no weapons and quite often they did not even wear military uniforms. These non-Muslims were gathered in labor battalions where no Turks were enlisted. They were allegedly forced to work under very bad conditions. The prevailing and widespread point of view on the matter was that wishing to partake in the World War II, Turkey gathered in advance all unreliable non-Turkish men regarded as a “fifth column”.

On November 11, 1942, Turkey instaured the Varlık Vergisi, a tax mostly levied on non-Muslim citizens with the stated aim of raising funds for the country's defense in case of an eventual entry into World War II. The tax was supposed to be paid by all citizens of Turkey, but inordinately higher rates were imposed on the country's non-Muslim inhabitants, in an arbitrary and predatory way.[50] The underlying reason for the tax was to inflict financial ruin on the minority non-Muslim citizens of the country,[51] end their prominence in the country's economy[52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60] and transfer the assets of non-Muslims to the Muslim bourgeoisie.[61] It was a discriminatory measure which taxed non-Muslims up to ten times more heavily and resulted in a significant amount of wealth and property being transferred to Muslims.[62] It was imposed on the fixed assets, such as landed estates, building owners, real estate brokers, businesses, and industrial enterprises of all citizens, but especially targeted the minorities.

Although the tax affected several non-Muslims groups in Turkey like Jews, Greeks, Armenians, Assyrians, some Kurds, and Levantines,[63] who controlled a large portion of the economy,[64] it was Armenians who were most heavily taxed.[65]

| Population group | Amount of taxes to be paid[66][67][68] |

|---|---|

| Christian Armenians | 232% |

| Jews | 179% |

| Christian Greeks | 156% |

| Muslims | 4.94% |

These taxes led to the destruction of the remaining non-Muslim merchant class in Turkey,[69][70][71] the lives and finances of many non-Muslim families were ruined.[72][73] The taxes were very high, some times higher than a person's entire wealth.[74] This resulted in a number of suicides of ethnic minority citizens in Istanbul.[75][76]

In September 1955, the state-sponsored Istanbul pogrom took place. The main target of the pogroms were Greeks, but Armenians were attacked as well.[77] The material damage was considerable, with damage to 5317 properties. The American consulate estimates that 59% of the businesses were Greek-owned, 17% were Armenian-owned, 12% were Jewish-owned, and 10% were Muslim-owned; while 80% of the homes were Greek-owned, 9% were Armenian-owned, 3% were Jewish-owned, and 5% were Muslim-owned.[78]

In 1974 new legislation was passed that stated that non-Muslim trusts could not own more property than that which had been registered under their name in 1936.[79][80][81][82] As a result, more than 1,400 assets (included churches, schools, residential buildings, hospitals, summer camps, cemeteries, and orphanages) of the Istanbul Armenian community since 1936 were retrospectively classified as illegal acquisitions and seized by the state.[83][81][84] Under the legislation, the Turkish courts rendered Turkish citizens of non-Turkish descent as "foreigners", thereby placing them under the same legal regulations of any foreign company or property holder living outside of Turkey who was not a Turkish national.[85] The provisions further provided that foundations belonging to non-Muslims are a potential "threat" to national security.[85] The process involved returning any property acquired after 1936, whether through lottery, will, donation, or purchase, to their former owners or inheritors. If former owners had died leaving no inheritors, the property was to be transferred to specified governmental agencies such as the Treasury or the Directorate General of Foundations.[86]

On 3 May 1984, a hit-team headed attack undertaken by Grey Wolves member[87] Abdullah Çatlı and paid for by the Turkish National Intelligence Organization.[88][89][90][91] committed the Alfortville Armenian Genocide Memorial bombings, an attack on a heavily Armenian populated district of Alfortville, Val-de-Marne, Île-de-France.[90] The target chosen for the attack was a memorial dedicated to the victims of the Armenian genocide on the rue Étienne Dolet which was inaugurated on 24 April 1984, the 69th anniversary of the Armenian genocide.[90] The Turkish press denounced the monument as a "monument of hate".[90][92] About a week after the inauguration, three bombs were reported to have exploded on 3 May 1984, resulting in thirteen injuries, two of them serious.[91][93] The monument, made of Khachkar stone, was severely damaged in the blasts.

Contemporary

[edit]

"The new generations are being taught to see Armenians not as human, but [as] an entity to be despised and destroyed, the worst enemy. And the school curriculum adds fuel to the existing fires."

Anti-Armenian sentiment persists in Turkey on institutional and social levels. Turkish professor Cenk Saraçoğlu argues that anti-Armenian attitudes in Turkey "are no longer constructed and shaped by social interactions between the 'ordinary people' ... Rather, the Turkish media and state promote and disseminate an overtly anti-Armenian discourse."[95]

The term 'Armenian' is frequently used in politics to discredit political opponents.[7] In 2008, Canan Arıtman, a deputy of İzmir from the Republican People's Party (CHP), called President Abdullah Gül an 'Armenian'.[4][5] Arıtman was then prosecuted for "insulting" the president.[4][7][96] Similarly, in 2010, Turkish journalist Cem Büyükçakır approved a comment on his website claiming that President Abdullah Gül's mother was an Armenian.[97] Büyükçakır was then sentenced to 11 months in prison for “insulting President [Abdullah] Gül”.[97][98][99]

In February 2004, the journalist Hrant Dink published an article in the Armenian newspaper Agos titled "The Secret of Sabiha Hatun" in which a former Gaziantep resident, Hripsime Sebilciyan, claimed to be Sabiha Gökçen's niece, implying that the Turkish nationalist hero Gökçen had Armenian ancestry.[100][101][102] The mere notion that Gökçen could have been Armenian caused an uproar throughout Turkey as Dink himself even came under fire, most notably by newspaper columnists and Turkish ultra-nationalist groups, which labeled him a traitor.[citation needed]

In 2010, during a football match between Bursaspor and Beşiktaş J.K., fans of Bursaspor chanted: "Armenian dogs support Beşiktaş".[4] The chant was presumably in reference to the fact that Alen Markaryan, the leader of the Beşiktaş fan base, is of Armenian descent.[103][104][105]

In March 2015, the mayor of Ankara, Melih Gökçek, filed a formal complaint on defamation charges against journalist Hayko Bağdat because he called him an Armenian. The complainant's petitioned that the statements by the journalist are "false and include insult and libel".[106] Gökçek stated that the term "Armenian" meant "disgust".[107] Gökçek sued Bağdat for 10,000 liras under a civil lawsuit. In another case Bağdat was initially sentenced to 105 days imprisonment for insulting Gökçek with the term Armenian. The sentence was converted into a fine of 1,160 Turkish Lira.[108]

In September 2015, during the Kurdish–Turkish conflict, a video was released which captured police in Cizre announcing on a loudspeaker to the local Kurdish population that they were "Armenian bastards".[109][110] A few days later, in another instance, the Cizre police made repeated announcements on loudspeaker saying "You are all Armenians" (external link of video).[6][111] The police had also announced: "Armenian offspring, tonight will be your last night".[112] On September 11, towards the end of the siege, the police made a final announcement saying: "Armenian bastards, we will kill you all, and we will exterminate you".[112]

"For decades, the governments in Turkey tried to wipe Anatolia of any traces of Armenian identity. Murders and forced immigration were not sufficient. Names of towns, streets, even recipes were altered. Their churches became mosques. They attempted to rewrite history. Now, [they are] telling the people of Cizre, under curfew for nine days, 'You are all Armenians.' This shows us the fabricated 'one nation, one belief’ has collapsed. They have failed to destroy the Armenian ghosts of history."

On 9 September 2015, a crowd of Turkish youth rallying in Armenian populated districts of Istanbul chanted "We must turn these districts into Armenian and Kurdish cemeteries."[113]

During the official state funeral of Turkish serviceman Olgun Karakoyunlu in 2015, a man exclaimed: "The PKK are all Armenians, but are hiding. I am Kurdish and a Muslim, but I am not an Armenian. The end of Armenians is near. God willingly, we will bring an end to them. Oh Armenians, whatever you do it is in vain, we know you well. Whatever you do will be in vain."[114] Similarly, in 2007, a state-appointed imam, presiding over a funeral of a Turkish soldier killed by the PKK, said that the death was due to "Armenian bastards".[115]

In January 2016, when Aras Özbiliz, an ethnic Armenian soccer player, was transferred to the Beşiktaş J.K. Turkish soccer team, a broad hate campaign arose throughout various social media outlets. Çarşı, the supporter group for Beşiktaş, released a statement condemning the racist campaign and reaffirming that it was against racism.[116] The hate campaign also prompted various politicians, including Selina Doğan of the Republican People's Party, to issue a statement condemning it.[117]

In March 2016, a parade conducted in Aşkale, initially dedicated to Turkish martyrs of World War I, turned into "a hate show" and a "hate-filled propaganda against the Armenians."[118][119] During the parade, Enver Başaran, the mayor of Aşkale, expressed gratitude to the "glorious ancestors who extirpated the Armenians".[119]

In April 2016, Barbaros Leylani, the head of the Turkish Worker's Union in Sweden, referred to Armenians as "dogs" in a public speech in Stockholm, and added: "Turks awaken! Armenian scums must be finished, die Armenian scums, die, die!" (external link of speech (in Turkish))[120][121] Juridikfronten, a Swedish watchdog organization, filed a report to the police due to an "incitement to racial hatred". Thereafter, Leylani resigned from his post.[120]

Incidents of violence against Armenians

[edit]

Hrant Dink, the editor of the Agos weekly Armenian newspaper, was assassinated in Istanbul on January 19, 2007, by Ogün Samast. He was reportedly acting on the orders of Yasin Hayal, a militant Turkish ultra-nationalist.[124][125] For his statements on Armenian identity and the Armenian genocide, Dink had been prosecuted three times under Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code for "insulting Turkishness."[126][127] He had also received numerous death threats from Turkish nationalists who viewed his "iconoclastic" journalism (particularly regarding the Armenian genocide) as an act of treachery.[128]

İbrahim Şahin and 36 other alleged members of Turkish ultra-nationalist Ergenekon group were arrested in January, 2009 in Ankara. The Turkish police said the roundup was triggered by orders Şahin gave to assassinate 12 Armenian community leaders in Sivas.[129][130] According to the official investigation in Turkey, Ergenekon also had a role in the murder of Hrant Dink.[131]

Sevag Balikci, a Turkish soldier of Armenian descent, was shot dead on April 24, 2011, the day of the commemoration of the Armenian genocide during his military service in Batman.[132] It was later discovered that killer Kıvanç Ağaoğlu was an ultra-nationalist.[133] Through his Facebook profile, it was uncovered that he was a sympathizer of nationalist politician Muhsin Yazıcıoğlu and Turkish agent / contract killer Abdullah Çatlı, who himself had a history of anti-Armenian activity, such as the Armenian Genocide Memorial bombing in a Paris suburb in 1984.[134][135][136] His Facebook profile also showed that he was a Great Union Party (BBP) sympathizer, a far-right nationalist party in Turkey.[134] Testimony given by Sevag Balıkçı's fiancée stated that he was subjected to psychological pressure at the military compound.[137] She was told by Sevag over the phone that he feared for his life because a certain military serviceman threatened him by saying, "If war were to happen with Armenia, you would be the first person I would kill."[137][138]

On February 26, 2012, on the anniversary of the Khojaly Massacre, the Atsız Youth led a demonstration took place in Istanbul which contained hate speech and threats towards Armenia and Armenians.[139][140][141][142] Chants and slogans during the demonstration include: "You are all Armenian, you are all bastards", "bastards of Hrant [Dink] can not scare us", and "Taksim Square today, Yerevan Tomorrow: We will descend upon you suddenly in the night."[139][140]

In November, 2012 the ultra-nationalist ASIM-DER group (founded in 2002) had targeted Armenian schools, churches, foundations and individuals in Turkey as part of an anti-Armenian hate campaign.[143]

On 23 February 2014, a group of protesters carrying a banner that said, "Long live the Ogun Samasts! Down with Hrant Dink!" paraded in front of an Armenian elementary school in Istanbul and then marched in front of the main building of the Agos newspaper, the same location where Hrant Dink was assassinated in 2007.[144][145]

Armenian genocide denial

[edit]

The Turkish government continues to aggressively deny the Armenian genocide. This position has been criticized in a letter from the International Association of Genocide Scholars to – then Turkish Prime Minister, now President – Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.[147]

In 2004, Belge Films, the film's distributor in Turkey pulled the release of Atom Egoyan's Ararat film, about the Armenian genocide, after receiving threats from the Ülkü Ocakları, an ultra nationalist organization.[148][149][150][151] This organization was behind similar threat campaigns against the Armenian community in the past. In 1994, hate mail signed by Ülkü Ocakları was sent to Armenian owned businesses and private homes describing Armenians as 'parasites' and that the massacres of the past will resume.[152] The letters also concluded by saying: "Do not forget: Turkey belongs only to the Turks. We will free Turkey of this exploitation. Don’t force us to send you to Yerevan! So leave now, before we do! Or else, it will boil down, as our Prime Minister (Tansu Çiller.) said, to: ‘either you put an end to it, or else we will.’ That is a final warning!"[152]

On 20 February 2015, the Mayor of Bayburt Mete Memis called the deeds of Turkish soldiers who massacred Armenians a hundred years ago "heroism". He made a congratulatory statement on the 97th anniversary of Bayburt's sacking, in which its Armenian resident were massacred and exiled as part of the Armenian genocide, claiming that 97 years ago, the Turkish soldiers in Bayburt had "written their name in history for defending the homeland."[153]

In August 2020 the statue of Komitas in Paris has been vandalized. The inscription "it is false" has been written in red ink on the plinth of the Armenian Genocide Memorial.[154][155]

Textbooks controversies

[edit]School textbooks in Turkey have been criticized for their negative depictions of Armenians and explicit denial of the Armenian Genocide and other Ottoman-era massacres.

Education in Turkey is centralized: its policy, administration and content are each determined by the Turkish government. Textbooks taught in schools are either prepared directly by the Ministry of National Education (MEB) or must be approved by its Instruction and Education Board. In practice, this means that the Turkish government is directly responsible for what textbooks are taught in all schools, even private education or those that are dedicated to ethnic minorities.[156][157] The state uses this monopoly to promote the official position of Armenian Genocide denial.[158][159]: 105

In 2014, Taner Akçam, writing for the Armenian Weekly, discussed 2014–2015 Turkish elementary and middle school textbooks that the MEB had made available on the internet. He found that Turkish history textbooks are filled with the message that Armenians are people "who are incited by foreigners, who aim to break apart the state and the country, and who murdered Turks and Muslims." The Armenian Genocide is referred to as the "Armenian matter", and is described as a lie perpetrated to further the perceived hidden agenda of Armenians. Recognition of the Armenian Genocide is defined as the "biggest threat to Turkish national security".[156]

Textbooks have also included demonization of Armenians, presenting them as enemies.[160][161] Historian Tunç Aybak states, "These officially distributed educational material reconstruct the history in line with the denial policies of the government portraying the Armenians as the back stabbers and betrayers who are regarded as a threat to the sovereignty and identity of the modern Turkey. The racialization of the Armenian ‘problem’ has now become an integral part of the official denial strategy sponsored by the Turkish government and intellectuals of geopolitical state craft and sustained through the institutions of the Turkish state.[160]

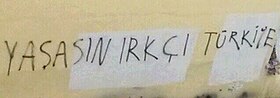

Vandalism

[edit]

In 2002, a monument was erected in memory of Turkish-Armenian composer Onno Tunç in Yalova, Turkey.[162] The monument to the composer of Armenian origin was subjected to much vandalism over the course of the years, in which unidentified people had taken out the letters on the monument. In 2012 Yalova Municipal Assembly decided to remove the monument. Bilgin Koçal, the former mayor of Yalova, informed the public that the memorial had been destroyed by time and that it would shortly be replaced with a new one in the memory of Tunç.[163][164][165]

In February 2015, graffiti was discovered near the wall of an Armenian church in the Kadıköy district of Istanbul saying, "You’re Either Turkish or Bastards" and "You Are All Armenian, All Bastards".[166][167][168] It is claimed that the graffiti was done by organizing members of a rally entitled "Demonstrations Condemning the Khojali Genocide and Armenian Terror." The Human Rights Association of Turkey petitioned the local government of Istanbul calling it a "Pretext to Incite Ethnic Hate Against Armenians in Turkey".[166][169] In the same month banners celebrating the Armenian genocide were spotted in several cities throughout Turkey. They declared: "We celebrate the 100th anniversary of our country being cleansed of Armenians. We are proud of our glorious ancestors." (Yurdumuzun Ermenilerden temizlenişinin 100. yıldönümü kutlu olsun. Şanlı atalarımızla gurur duyuyoruz.)[146][170]

In March 2015, graffiti was discovered on the walls of an Armenian church in the Bakırköy district of Istanbul which read "1915, blessed year", in reference to the Armenian genocide of 1915. Other slurs included "What does it matter if you are all Armenian when one of us is Ogün Samast," which was in reference to the slogan "We are all Armenian" used by demonstrators after the assassination of Hrant Dink.[171] The administrator of the church remarked "This type of thing happens all the time."[171]

In September 2015, a 'Welcome' sign was installed in Iğdır and written in four languages, Turkish, Kurdish, English, and Armenian. The Armenian portion of the sign was protested by ASIMDER who demanded its removal.[172] In October 2015, the Armenian writing on the 'Welcome' sign was heavily vandalized.[173] The Armenian portion of the sign was ultimately removed in June 2016.[174]

In April 2018, a graffiti reading “This homeland is ours” was inscribed on the wall and a pile of trash was also dumped in front of the Armenian Surp Takavor Church in Kadıköy district. Kadıköy Municipality condemned and described the action as a “racist attack” in a Twitter post, saying the necessary work has been initiated to clear the writing and remove the trash.[175]

Official statements

[edit]On 5 August 2014, then Prime Minister, now President of Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, in a televised interview on NTV news network, remarked that being Armenian is "uglier" even than being Georgian, saying "You wouldn't believe the things they have said about me. They have said I am Georgian ... they have said even uglier things - they have called me Armenian, but I am Turkish."[176][177][178]

On 3 June 2015, during an election campaign speech in Bingöl directed against opposition party HDP, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan stated that the "Armenian lobby, homosexuals and those who believe in 'Alevism without Ali' – all these representatives of sedition are [the HDP’s] benefactors."[179]

On 24 June 2015, after a concert by Tigran Hamasyan in Ani, a ruined medieval Armenian city-site situated in the Turkish province of Kars, the president of Ülkü Ocakları of the Kars district, Tolga Adıgüzel, threatened to 'hunt down' Armenians in the streets of Kars.[180][181]

After the June 2015 Turkish general election, when three Armenian MPs were elected to the Grand National Assembly, Hüseyin Sözlü, the mayor of Adana, reacted in a Twitter post: "Manukyan's nephew in Adana must be very happy now. His three cousins have entered the Parliament. They are from the AKP, the CHP and the HDP."[181][182] Sözlü alluded that the three Armenian MPs were related to Matild Manukyan, a Turkish-Armenian businesswoman who is known to have owned several brothels.[181]

Media

[edit]The Ankara Chamber of Commerce included a documentary, accusing the Armenian people of slaughtering Turks, with its paid tourism advertisements in the June 6, 2005 edition of the magazine Time Europe. The magazine later apologized for allowing the inclusion of the DVDs and published a critical letter signed by five French organizations.[183][184] The February 12, 2007, edition of Time Europe included an acknowledgment of the truth of the Armenian genocide and a DVD of a documentary by French director Laurence Jourdan about the genocide.[185]

Influence on Turkish national identity

[edit]The Armenian genocide itself played a key role in the destruction of the Ottoman Empire and the foundation of the Turkish republic.[186][187][188][189] From the founding of the republic, the genocide has been viewed as a necessity and raison d'état.[190][191] Many of the main perpetrators, including Talaat Pasha, were hailed as national heroes of Turkey; many schools, streets, and mosques are still named after them.[192][193][194] Historian Erik-Jan Zürcher argues that, since the Turkish nationalist movement dependent on the support of a broad coalition of actors that benefited from the genocide, it was impossible to break with the past.[195] Turkish historian Doğan Gürpınar says that acknowledging the genocide would bring into question the foundational assumptions of the Turkish nation-state.[196]

The mass confiscation of Armenian properties was an important factor in forming the economic basis of the Turkish Republic while endowing the Turkish economy with capital. The appropriation led to the formation of a new Turkish bourgeoisie and provided the opportunity for lower class Turks (peasantry, soldiers, and laborers) to rise to the ranks of the middle class.[197] Turkish historian Uğur Ümit Üngör asserts that "the elimination of the Armenian population left the state an infrastructure of Armenian property, which was used for the progress of Turkish (settler) communities. In other words: the construction of an étatist Turkish "national economy" was unthinkable without the destruction and expropriation of Armenians."[198]

Turkish nationalists have taken to trials people like the Nobel Prize–winning Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk, the Turkish novelist Elif Shafak, and the late Hrant Dink[199] for acknowledging the existence of the Armenian genocide, accusing them of insulting Turkey.

See also

[edit]- Anti-Armenian sentiment

- Anti-Armenian sentiment in Azerbaijan

- Armenia–Turkey relations

- Armenian genocide

- Armenian genocide denial

- Armenian genocide recognition

- Armenian question

- Armenians in the Ottoman Empire

- Armenians in Turkey

- Confiscation of Armenian properties in Turkey

- Hidden Armenians

- Neo-Ottomanism

- Racism and discrimination in Turkey

- Terminology of the Armenian genocide

- Turkish nationalism

- Turkish textbook controversies

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Law No. 1042 of the Republic of Turkey, 23 May 1927

- References

- ^ a b "Khojali: A Pretext to Incite Ethnic Hatred". Armenian Weekly. 22 February 2015.

- ^ "Turkish citizens mistrust foreigners, opinion poll says". Hürriyet Daily News. 2 May 2011.

- ^ "Minority Rights Group International: Turkey: Armenians". Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ a b c d e Özdoğan, Günay Göksu; Kılıçdağı, Ohannes (2012). Hearing Turkey's Armenians: Issues, Demands and Policy Recommendations (PDF). İstanbul: Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation (TESEV). p. 26. ISBN 978-605-5332-01-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ a b c "CHP deputy Arıtman unapologetic as Gül denies Armenian roots". Today's Zaman. 22 December 2008. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ a b c d "Grew up Kurdish, forced to be Turkish, now called Armenian". al-monitor.com. 9 October 2015. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ a b c Schrodt, Nikolaus (2014). Modern Turkey and the Armenian Genocide: An Argument About the Meaning of the Past. Springer. p. 10. ISBN 978-3-319-04927-4.

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (1993). Looking Toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History. Indiana University Press. pp. 3, 30. ISBN 978-0-253-20773-9.

- ^ Suny 2015, p. xiv.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 26–27, 43–44.

- ^ Communal Violence: The Armenians and the Copts as Case Studies, by Margaret J. Wyszomirsky, World Politics, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Apr., 1975), p. 438

- ^ Suny 2015, p. 105.

- ^ "Hamidian (Armenian) Massacres (1894-1986)".

- ^ Raymond H. Kévorkian, "The Cilician Massacres, April 1909" in Armenian Cilicia, eds. Richard G. Hovannisian and Simon Payaslian. UCLA Armenian History and Culture Series: Historic Armenian Cities and Provinces, 7. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers, 2008, pp. 339-69.

- ^ Adalian, Rouben Paul (2012). "The Armenian Genocide". In Totten, Samuel; Parsons, William S. (eds.). Century of Genocide. Routledge. pp. 117–56. ISBN 978-0-415-87191-4.

- ^ Adalian, Rouben Paul (2010). "Adana Massacre". Historical Dictionary of Armenia. Scarecrow Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-8108-7450-3.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 127–129, 133, 170–171.

- ^ Göçek 2015, pp. 62, 150.

- ^ a b Maksudyan, Nazan (2019). ""This Is a Man's World?": On Fathers and Architects". Journal of Genocide Research. 21 (4): 540–544 [542]. doi:10.1080/14623528.2019.1613816. S2CID 181910618.

Turkish nationalists were following the pattern that was firmly established after the Hamidian massacres, though new research might take the chronology of unpunished crimes and denial further back to the first half of the nineteenth century. In each and every case of violence against the non-Muslims, the first reaction of the state – even though the regime changed, along with the involved actors – was denial.

- ^ Göçek 2015, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 154–155, 189.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 137.

- ^ Suny 2015, p. 185.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Suny 2015, p. 218.

- ^ a b Suny 2015, pp. 243–244.

- ^ Dadrian 2003, p. 277.

- ^ Kaligian 2014, p. 217.

- ^ Suny 2015, p. 236.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. 225.

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 244–245. "Any incident of Armenian resistance, any discovery of a cache of arms, was transformed into a vision of a coordinated widespread Armenian insurrection... Deportations ostensibly taken for military reasons rapidly radicalized monstrously into an opportunity to rid Anatolia once and for all of those peoples perceived to be an imminent existential threat to the future of the empire."

- ^ Akçam, Taner (2019). "When Was the Decision to Annihilate the Armenians Taken?". Journal of Genocide Research. 21 (4): 457–480 [457]. doi:10.1080/14623528.2019.1630893. S2CID 199042672.

Most scholars placed the possible date(s) for a final decision at the end of March (or beginning of April).

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Ihrig 2016, p. 109.

- ^ Dadrian 2003, p. 274.

- ^ Kaiser, Hilmar (2010). "Genocide at the Twilight of the Ottoman Empire". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 383. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

The Armenian deportations were not the result of an Armenian rebellion. On the contrary, Armenians were deported when no danger of outside interference existed. Thus Armenians near front lines were often slaughtered on the spot and not deported. The deportations were not a security measure against rebellions but depended on their absence.

- ^ Suny 2009, p. 945. "A newly minted doctor of history, Fuat Dündar, showed with his careful reading of Ottoman archival documents how the deportations had been organized and carried out by the Turkish authorities, and—most shocking of all—that Minister of the Interior Talat, the chief initiator, had been aware that sending people to the Syrian desert outpost of Der Zor meant certain death."

Dadrian 2003, p. 275. "As diplomat after diplomat from allied Germany and Austria (as well as American Ambassador to Turkey Henry Morgenthau) repeatedly averred, by dispatching the victim population to these deserts the Turks were dispatching them to death and ruination. Even the Chief of Staff of the Ottoman Fourth Army in control of these areas in his memoirs debunked and ridiculed the pretense of 'relocation.'" - ^ Dadrian & Akçam 2011, p. 18.

- ^ Morris, Benny; Ze'evi, Dror (2019). The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey's Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924. Harvard University Press. p. 486. ISBN 978-0-674-91645-6.

- ^ Ekmekçioğlu 2016, p. 4.

- ^ Akçam 2012, pp. 289–290, 331.

- ^ Dixon 2010, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Akçam 2012, p. 341. "On the basis of existing Interior Ministry Papers from the period, it can confidently be asserted that the goal of the CUP was not the resettlement of Anatolia's Armenian population and their just compensation for the property and possessions that they were forced to leave behind. Rather, the confiscation and subsequent use of Armenian property clearly demonstrated that Unionist government policy was intended to completely deprive the Armenians of all possibility of continued existence."

- ^ Gilbert Gidel; Albert Geouffre de Lapradelle; Louis Le Fur; André Nicolayévitch Mandelstam; Cómité des réfugiés arménins (1929). Confiscation des biens des réfugiés arméniens par le gouvernement turc (in French). Le Fur. pp. 87–90.

- ^ Lekka, Anastasia (Winter 2007). "Legislative Provisions of the Ottoman/Turkish Governments Regarding Minorities and Their Properties". Mediterranean Quarterly. 18 (1): 135–154. doi:10.1215/10474552-2006-038. ISSN 1047-4552. S2CID 154830663.

- ^ Baghdjian 2010, p. 191.

- ^ a b Der Matossian, Bedross (6 October 2011). "The Taboo within the Taboo: The Fate of 'Armenian Capital' at the End of the Ottoman Empire". European Journal of Turkish Studies. 37. doi:10.4000/ejts.4411. ISSN 1773-0546. S2CID 143379202.

- ^ Melkonyan, Ruben. "ON SOME PROBLEMS OF THE ARMENIAN NATIONAL MINORITY IN TURKEY" (PDF). p. 2.

- ^ "Varlik vergisi (asset tax) - one of the many black chapters of Turkish history..." Assyrian Chaldean Syriac Association. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ Nowill, Sidney E. P. (December 2011). Constantinople and Istanbul: 72 Years of Life in Turkey. Matador. p. 77. ISBN 978-1848767911."In reality, the idea was to reduce the influence of the minority non-Turkish citizens to the country's affairs."

- ^ Ince, Basak (April 2012). Citizenship and Identity in Turkey: From Atatürk's Republic to the Present Day. I. B. Tauris. p. 75. ISBN 978-1780760261."These quotations reveal that the real reason for the Wealth Tax was the elimination of non-Muslims from the economy."

- ^ Ince, Basak (April 2012). Citizenship and Identity in Turkey: From Atatürk's Republic to the Present Day. I. B. Tauris. p. 75. ISBN 978-1780760261."However, the underlying reason was the elimination of minorities from the economy, and the replacement of the non-Muslim bourgeoisie by its Turkish counterpart."

- ^ C. Fortna, Benjamin; Katsikas, Stefanos; Kamouzis, Dimitris; Konortas, Paraskevas (December 2012). State-Nationalisms in the Ottoman Empire, Greece and Turkey: Orthodox and Muslims, 1830-1945 (SOAS/Routledge Studies on the Middle East). Routledge. p. 195. ISBN 978-0415690560."... an attempt was being made by means of the Wealth Tax to eliminate the minorities who occupied an important place in Turkey's commercial life."

- ^ Akıncılar, Nihan; Rogers, Amanda E.; Dogan, Evinc; Brindisi, Jennifer; Alexieva, Anna; Schimmang, Beatrice (December 2011). Young Minds Rethinking the Mediterranean. Istanbul Kultur University. p. 23. ISBN 978-0415690560."The first visible attempt in order to remove minorities from economic life was the implementation of 'Wealth Tax' in 1942 which was accepted in the National Assembly with the claim of balancing and distributing properties of minorities. The actual aim behind the scenes was to impoverish the non-Muslim minorities and eliminate them from the competition in the national economy. Instead, the RPP government tried to create a new wealthy Turkish Muslim bourgeoisie."

- ^ Turam, Berna (January 2012). Secular State and Religious Society: Two Forces in Play in Turkey. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 43. ISBN 978-0230338616."With the introduction of the Varlik Vergisi (capital tax) in 1942, which aimed to confiscate the property and assets of non-Muslims, an attempt was made to bring the national economy also under the control of Muslim citizens."

- ^ Çetinoğlu, Sait (2012). "The Mechanisms for Terrorizing Minorities: The Capital Tax and Work Battalions in Turkey during the Second World War". Mediterranean Quarterly. Vol. 23. DUKE University Press. p. 14. doi:10.1215/10474552-1587838. S2CID 154339814."The aim was to destroy the economic and cultural base of these minorities, loot their properties and means of livelihood, and, at the same time "turkify" the economy of Turkey."

- ^ Egorova, Yulia (July 2013). Jews, Muslims and Mass Media: Mediating the 'Other. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 978-0253005267."That tax was instrumental in transferring the control of the market from the non-Muslim groups to the Muslims."

- ^ Brink-Danan, Marcy (December 2011). Jewish Life in Twenty-First-Century Turkey: The Other Side of Tolerance (New Anthropologies of Europe). Indiana University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0253223500."Varlik Vergisi is commonly translated as "Capital Tax" or "Wealth Tax" we might, however, consider an alternate translation of varlik as "presence" which focuses attention on the devaluation- both financial and political of minority presence during this time"

- ^ Guttstadt, Corry (May 2013). Turkey, the Jews, and the Holocaust. Cambridge University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0521769914."... We will use it to eliminate the foreigners who control the market and hand the Turkish market over the Turks." "The foreigners to be eliminated" referred primarily to the non-Muslims citizens of Turkey."

- ^ Şakir Dinçşahin, Stephen Goodwin, "Towards an Encompassing Perspective on Nationalism: The Case of Jews in Turkey during Second World War, 1939-1945"

- ^ Kuru, Ahmet T.; Stepan, Alfred (21 February 2012). Democracy, Islam, and Secularism in Turkey. Columbia University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-231-53025-5.

- ^ Nowill, Sidney E. P. (December 2011). Constantinople and Istanbul: 72 Years of Life in Turkey. Matador. p. 77. ISBN 978-1848767911."Those mainly afflicted were the Greeks, Jews, Armenians, and, to some extent, foreign-passport Levantine families."

- ^ Güven, Dilek (2005-09-06). "6-7 Eylül Olayları (1)". Türkiye. Radikal (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 4 November 2005. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

Nitekim 1942 yılında yürürlüğe giren Varlık Vergisi, Ermenilerin, Rumların ve Yahudilerin ekonomideki liderliğine son vermeyi hedeflemiştir...Seçim dönemleri CHP ve DP'nin Varlık Vergisi'nin geri ödeneceği yönündeki vaatleri ise seçim propagandasından ibarettir.

- ^ Smith, Thomas W. (August 29 – September 2, 2001). Constructing A Human Rights Regime in Turkey: Dilemmas of Civic Nationalism and Civil Society (PDF). American Political Science Association Annual Conference San Francisco. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-03-18.

One of the darkest events in Turkish history was the Wealth Tax, levied discriminatory against non-Muslims in 1942, hobbling Armenians with the most punitive rates.

- ^ Corry Guttstadt: Turkey, the Jews, and the Holocaust. Cambridge University Press, 2013. p. 75

- ^ Andrew G. Bostom: The Legacy of Islamic Antisemitism: From Sacred Texts to Solemn History. Prometheus Books; Reprint edition, 2008. p. 124

- ^ Nergis Erturk: Grammatology and Literary Modernity in Turkey. Oxford University Press, 2011. p. 141

- ^ Kasaba, Reşat (June 2008). The Cambridge History of Turkey (Volume 4). Cambridge University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0521620963."But in its application it differentiated between Muslim and non-Muslim taxpayers, and levied far heavier taxes on non-Muslims, leading to the destruction of the remaining non-Muslim merchant class in Turkey."

- ^ Brink-Danan, Marcy (December 2011). Jewish Life in Twenty-First-Century Turkey: The Other Side of Tolerance (New Anthropologies of Europe). Indiana University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0253223500."Further, the Varlik Vergisi, an excessive tax instituted during World War II, pilfered small Jewish (and other minority) businesses to the point of bankruptcy"

- ^ Ince, Basak (April 2012). Citizenship and Identity in Turkey: From Atatürk's Republic to the Present Day. I. B. Tauris. p. 76. ISBN 978-1780760261."Due to the law, most non-Muslim merchants sold their properties and vanished from the markets."

- ^ Kasaba, Reşat (June 2008). The Cambridge History of Turkey (Volume 4). Cambridge University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0521620963."As a consequence of Varlık Vergisi and the labour camps, the lives and finances of many non-Muslim families were ruined."

- ^ Egorova, Yulia (July 2013). Jews, Muslims and Mass Media: Mediating the 'Other. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 978-0253005267."..., by the time that tax was abolished the major Greek, Armenian and Jewish merchant figures were shaken and dislocated."

- ^ Bayir, Derya (January 2013). Minorities and Nationalism in Turkish Law. Routledge. ISBN 978-1409420071.

- ^ Nowill, Sidney E. P. (December 2011). Constantinople and Istanbul: 72 Years of Life in Turkey. Matador. p. 78. ISBN 978-1848767911."The Varlık resulted in a number of suicides of ethnic minority citizens in Istanbul, indeed, I saw one myself. One evening while on a ferryboat I saw a man jump off the stern into the Bosphorus current."

- ^ Guttstadt, Corry (May 2013). Turkey, the Jews, and the Holocaust. Cambridge University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0521769914."Some people committed suicide in despair."

- ^ de Zayas, Alfred (August 2007). "The Istanbul Pogrom of 6–7 September 1955 in the Light of International Law". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 2 (2): 138. ISSN 1911-0359.

- ^ Hür, Ayşe (2008-09-07). "6–7 Eylül'de devletin 'muhteşem örgütlenmesi'". Taraf (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 2014-09-11. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ Varlık, Yasemin (2 July 2001). "Tuzla Ermeni Çocuk Kampı'nın İzleri". Bianet (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 6 December 2006.

- ^ Oran, Baskın (26 January 2007). "Bu kadarı da yapılmaz be Hrant!". Agos (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 1 March 2012.

- ^ a b Peroomian 2008, p. 277.

- ^ Susan, Fraser (28 August 2011). "Turkey to return confiscated property". The Guardian.

- ^ Bedrosyan, Raffi (17 April 2012). "Revisiting the Turkification of Confiscated Armenian Assets". Armenian Weekly.

- ^ Bedrosyan, Raffi (6 December 2012). "'2012 Declaration': A History of Seized Armenian Properties in Istanbul". Armenian Weekly.

- ^ a b Atılgan et al. 2012, p. 67.

- ^ Oran 2006, p. 85.

- ^ Atkins, Stephen E. (2004). Encyclopedia of modern worldwide extremists and extremist groups / äc Stephen E. Atkins. Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Greenwood Press. p. 110. ISBN 9780313324857.

- ^ Grosscup, Beau (1991). The new explosion of terrorism. Far Hills, NJ: New Horizon Pr. p. 297. ISBN 9780882820743. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ Ergenekon document reveals MİT’s assassination secrets Archived August 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Today's Zaman, 19 August 2008

- ^ a b c d Permanent Peoples' Tribunal (1985). Gerard Libaridian (ed.). A Crime of Silence: The Armenian Genocide. London: Zed Books. ISBN 9780862324230.

- ^ a b British Broadcasting Corporation. Monitoring Service (1984). Summary of World Broadcasts: Non-Arab Africa, Issues 7631-7657. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ Davidian, David (1989). Addressing Turkish genocide apologists : [on UNIX UseNet World Wide Computer Network. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Published by the Social Democratic Party of Armenia. ISBN 9781877935015.

- ^ The Middle East, Issues 111-122. IC Publications. 1984.

- ^ Şahan, İdil Engindeniz; Fırat, Derya; Şannan, Barış. "January-April 2014 Media Watch on Hate Speech and Discriminatory Language Report" (PDF). Hrant Dink Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-07. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ Saraçoğlu, Cenk (2011). Kurds of Modern Turkey: Migration, Neoliberalism and Exclusion in Turkish Society. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 175. ISBN 9780857719102.

- ^ Bekdil, Burak. "How Turkish are the Turks?". Hurriyet.

- ^ a b "11-Month Prison Sentence for 'Gul is Armenian' Comment". Armenian Weekly. November 6, 2010.

- ^ "Haberin Yeri Site Kurucusu Büyükçakır'a 11 Ay Hapis". Bianet (in Turkish). 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Turkish Journalist, Publisher Receive 11-Month Prison Sentence for Calling Gul Armenian". Asbarez. November 7, 2010.

- ^ Dink, Hrant (2004-02-06). "Sabiha Hatun'un Sırrı". Agos.

- ^ "Sabiha Gökçen or Hatun Sebilciyan?". Hürriyet. 2004-02-21. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ Kalkan, Ersin (2004-02-21). "Sabiha Gökçen mi Hatun Sebilciyan mı?". Hürriyet (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 2007-08-27. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ Cengiz, Orhan Kemal (10 December 2010). "'Armenian dogs support Beşiktaş' they say, but…". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Kerpiççiler, Cem (9 June 2013). "Canlı yayında cacık yaparsan taraftarı anlayamazsın!" (in Turkish). Posta.

- ^ Bir, Ali Atif (7 December 2010). "İğrenç slogan: "Ermeni köpekler, Beşiktaş'ı destek". Bugün. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Ankara mayor files complaint against journalist for calling him 'Armenian'". Today's Zaman. 24 March 2015.

- ^ "Columnist faces court for insulting Ankara mayor by calling him 'Armenian'". Today's Zaman. 27 September 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-09-27. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ "Armenian-origin columnist fined for 'insulting' Ankara mayor - Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News. 7 December 2015. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ Kivanc, Umit (10 September 2015). "Bildiklerimiz, bilmediklerimiz". Radikal.

- ^ "Impressions from Cizre: 'There is no PKK here, we are the people and we defend ourselves'". Sendika. 18 September 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Polis, Cizre'de halka böyle seslendi: Hepiniz Ermenisiniz". Cumhurriyet. 11 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Cizre "The Curfew" Report" (PDF). European Association of Lawyers for Democracy & World Human Rights. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-06. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ "Armenian-Populated Districts of Istanbul Attacked". Asbarez. 9 September 2015. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "'PKK'lıların hepsi Ermeni!'" (in Turkish). Sabah. 2 September 2015.

Bu PKK'lıların hepsi Ermeni, kendilerini saklıyorlar. Ben Kürdüm, Müslümanım ama ben Ermeni değilim. Ermenilerin sonu gelecek. Allah'ın izniyle sizin sonunuzu getireceğiz. Ne etseniz boş ey Ermeniler, biz sizi biliyoruz. Ne yapsanız boş Ermeniler

- ^ "Unearthing the past, endangering the future". Economist. 18 October 2007.

- ^ "çArşı'dan ırkçılığa karşı mesaj" (in Turkish). Demokrat Haber. 22 January 2016. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ "Selina Doğan'dan Aras Özbiliz'e tepki gösterenlere: Lefter de bir Rumdu!" (in Turkish). Demokrat Haber. 21 January 2016. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ Bulut, Uzay (5 April 2016). "Turkish Mayor: Our 'Glorious Ancestors Extirpated Armenians'". Clarion Project.

- ^ a b "Kurtuluş töreninde canlandırılan Ermeni katliamı çocukları korkuttu" (in Turkish). Dogan Haber Ajansi. 3 March 2016. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Insulting remarks about Armenia forces resignation in Sweden". Fox News. 11 April 2016.

- ^ "Turkish-Azerbaijani tandem engaged in anti-Armenian racist activities in Europe's heart". Armenpress. 11 April 2016.

- ^ "Samast'a jandarma karakolunda kahraman muamelesi". Radikal (in Turkish). 2 February 2007. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007.

- ^ Watson, Ivan (12 January 2012). "Turkey remembers murdered journalist". CNN.

- ^ Harvey, Benjamin (2007-01-24). "Suspect in Journalist Death Makes Threat". The Guardian. London. Associated Press. [dead link]

- ^ "Turkish-Armenian writer shot dead". BBC News. 2007-01-19. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007.

- ^ Robert Mahoney (2006-06-15). "Bad blood in Turkey" (PDF). Committee to Protect Journalists. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2007.

- ^ "IPI Deplores Callous Murder of Journalist in Istanbul". International Press Institute. 2007-01-22. Archived from the original on 3 March 2007.

- ^ Committee to Protect Journalists (2007-01-19). "Turkish-Armenian editor murdered in Istanbul". Archived from the original on 25 January 2007.

Dink had received numerous death threats from nationalist Turks who viewed his iconoclastic journalism, particularly on the mass killings of Armenians in the early 20th century, as an act of treachery.

- ^ Turkish police uncover arms cache, The Wall Street Journal, Jan. 10, 2009

- ^ "Ergenekon Arrests Preempt Coup Plan, Operation "Glove"". news.eirna.com. 13 January 2009. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Montgomery, Devin (2008-07-12). "Turkey arrests two ex-generals for alleged coup plot". JURIST. Archived from the original on 2008-12-26. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ "Armenian private killed intentionally, new testimony shows". Today's Zaman. 2012-01-27. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ "Sevag Şahin'i vuran asker BBP'li miydi?" (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ a b "Halavurt: "Sevag 24 Nisan'da Planlı Şekilde Öldürülmüş Olabilir"". Bianet (in Turkish). May 4, 2011. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

:Translated from Turkish: "On May 1, 2011, after investigating into the background of the suspect, we discovered that he was a sympathizer of the BBP. We also have encountured nationalist themes in his social networks. For example, Muhsin Yazicioglu and Abdullah Catli photos were present" according to Balikci lawyer Halavurt.

- ^ "Title translated from Turkish: What Happened to Sevag Balikci?". Radikal (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

Translated from Turkish: "We discovered that he was a sympathizer of the BBP. We also have encountered nationalist themes in his social networks. For example, Muhsin Yazicioglu and Abdullah Catli photos were present" according to Balikci lawyer Halavurt.

- ^ "Sevag'ın Ölümünde Şüpheler Artıyor". Nor Zartonk (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

Title translated from Turkish: Doubts emerge on the death of Sevag

- ^ a b "Fiancé of Armenian soldier killed in Turkish army testifies before court". News.am. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ "Nişanlıdan 'Ermenilerle savaşırsak ilk seni öldürürüm' iddiası". Sabah (in Turkish). 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

Title translated from Turkish: From the fiance: If we were to go to war with Armenia, I would kill you first"

- ^ a b "Azeris mark 20th anniversary of Khojaly Massacre in Istanbul". Hurriyet. February 26, 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

One banner carried by dozens of protestors said, 'You are all Armenians, you are all bastards.'

- ^ a b "Inciting Hatred: Turkish Protesters Call Armenians 'Bastards'". Asbarez. February 28, 2012. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

'Mount Ararat will Become Your Grave' Chant Turkish Students

- ^ "Khojaly Massacre Protests gone wrong in Istanbul: 'You are all Armenian, you are all bastards'". National Turk. 28 February 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Protests in Istanbul: "You are all Armenian, you are all bastards"". LBC International. 2012-02-26. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Ultra-nationalist group targets Turkey's Armenians". Zaman. 28 November 2012. Archived from the original on 29 November 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Agos'un önünde ırkçı eylem (English: In front of Agos a racist act)". BirGun. 23 February 2014. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014.

- ^ "EMO İstanbul Seçimlerinde faşist provokasyon". Turnusol (in Turkish). 23 February 2014.

- ^ a b Barsoumian, Nanore (23 February 2015). "Banners Celebrating Genocide Displayed in Turkey". Armenian Weekly.

- ^ "INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF GENOCIDE SCHOLARS". Archived from the original on April 16, 2006. Retrieved 27 February 2023. from the International Association of Genocide Scholars to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, June 13, 2005

- ^ "Egoyan award winning film not shown yet in Turkey". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 2008-02-02.

- ^ "Gray Wolves Spoil Turkey's Publicity Ploy on Ararat". Archived from the original on 2011-09-12. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ Ülkü Ocaklari: Ararat Yayinlanamaz (in Turkish)

- ^ Ülkü Ocaklari: ARARAT'I Cesaretiniz Varsa Yayinlayin ! (in Turkish)

- ^ a b Hofmann, Tessa (2002). Armenians in Turkey Today: A Critical Assessment of the Situation of the Armenian Minority in the Turkish Republic (PDF). Brussels: The EU Office of Armenian Associations of Europe.

- ^ "Turkish Mayor of Bayburt Calls Armenian Holocaust Heroism". Haberler. 20 February 2015. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ French MP Valerie Boyer condemns the profanation of Komitas statue in Paris, by Siranush Ghazanchyan, Public Radio of Armenia, August 31, 2020

- ^ Komitas statue vandalized in Paris, Panorama.am, August 31, 2020

- ^ a b Akcam, Taner (4 December 2014). "Akcam: Textbooks and the Armenian Genocide in Turkey: Heading Towards 2015". Armenian Weekly. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Ekmekçioğlu 2016, p. 7.

- ^ Göçek 2015, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Dixon 2010, pp. 103–126.

- ^ a b Aybak 2016, p. 13.

- ^ Galip, Özlem Belçim (2020). New Social Movements and the Armenian Question in Turkey: Civil Society vs. the State. Springer International Publishing. p. 186. ISBN 978-3-030-59400-8.

Additionally, for instance, the racism and language of hatred in officially approved school textbooks is very intense. These books still show Armenians as the enemies, so it would be necessary for these books to be amended...

- ^ BÜYÜKFURAN ARMUTLU, İbrahim (2002-06-11). "Onno Tunç anıtı açıldı". Hürriyet (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ "Turkish municipality destroys monument of Armenian musician, composer". Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ Helix Consulting LLC. "Monument to Armenian musician Onno Tunc destroyed in Turkey". Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ "Onno Tunç anıtını yıktık çünkü ..." Sabah (in Turkish). 30 April 2012. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ a b "İHD: Hocalı mitinginin amacı ırkçı nefreti kışkırtmak". IMC. 20 February 2015. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015.

- ^ Gunes, Deniz (20 February 2015). "Kadıköy esnafına ırkçı bildiri dağıtıldı" (in Turkish). Demokrat Haber. Archived from the original on 2015-02-21. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "İHD: Mitingin amacı ırkçı nefreti kışkırtmaktır" (in Turkish). Yüksekova Haber. 20 February 2015.

- ^ "Khojali: A Pretext to Incite Ethnic Hatred". Armenian Weekly. 22 February 2015.

- ^ "Irkçı afişte 1915 itirafı!". Demokrat Haber (in Turkish). 23 February 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-02-24. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ a b Karatas, Zeynep (25 March 2015). "İstanbul-based Armenian church daubed with hate messages". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 2015-03-27. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Kurdish Mayor of Igdir Installs 'Welcome' Sign in Armenian". Asbarez. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "İlçe girişindeki Ermenice yazıyı tahrip ettiler" (in Turkish). CNN Turk. 12 October 2015.

- ^ "Armenian Signboards Removed in Igdir". Asbarez. 21 June 2016.

- ^ Racist graffiti inscribed on Kadıköy church wall

- ^ Altintas, Baris (6 August 2014). "PM uses offensive, racist language targeting Armenians". Zaman.

- ^ Taylor, Adam (6 August 2014). "Is 'Armenian' an insult? Turkey's prime minister seems to think so". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Turkey's Erdogan accused of inciting racial hatred for comment on Armenian descent". The Republic. 6 August 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-08-12.

- ^ "Journalists, Armenians, gays are 'representatives of sedition,' Erdoğan says". Hürriyet. 3 June 2015.

- ^ "Ülkücü başkan coştu: "Sokaklarda Ermeni avına mı çıkalım?"" (in Turkish). Birgun. 24 June 2015.

Yoksa bizler de Kars caddelerinde Ermeni avına mı çıkalım?

- ^ a b c Kursun, Gunal (9 July 2015). "Textbook examples of hate crimes, hate speech and racism in Turkey". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 2015-07-11. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ Cengiz, Orhan Kemal (7 July 2015). "Hate speech freely targets Armenians". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 2015-07-09. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- ^ "In Turkey, a Clash of Nationalism and History", The Washington Post, 2005-09-29

- ^ "Time carries documentary, adopts policy on Armenian Genocide". February 3, 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-06-05.

- ^ Time magazine: Carries documentary, adopts policy on Armenian Genocide, Pseka, archived from the original on 2007-09-28

- ^ Bloxham 2005, p. 111. "The Armenian genocide provided the emblematic and central violence of Ottoman Turkey's transition into a modernizing nation state. The genocide and accompanying expropriations were intrinsic to the development of the Turkish Republic in the form in which it appeared in 1924."

- ^ Kévorkian 2011, p. 810. "This chapter of the history treated here [the trials] clearly illustrates the incapacity of the great majority to consider these acts punishable crimes; it confronts us with a self-justifying discourse that persists in our own day, a kind of denial of the "original sin," the act that gave birth to the Turkish nation, regenerated and re-centered in a purified space."

- ^ Göçek 2015, p. 19. "... what makes 1915–17 genocidal both then and since is, I argue, closely connected to its being a foundational violence in the constitution of the Turkish republic... the independence of Turkey emerged in direct opposition to the possible independence of Armenia; such coeval origins eliminated the possibility of acknowledging the past violence that had taken place only a couple years earlier on the one hand, and instead nurtured the tendency to systemically remove traces of Armenian existence on the other."

- ^ Suny 2015, pp. 349, 365. "The Armenian Genocide was a central event in the last stages of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the foundational crime that along with the ethnic cleansing and population exchanges of the Anatolian Greeks made possible the formation of an ethnonational Turkish republic... The connection between ethnic cleansing or genocide and the legitimacy of the national state underlies the desperate efforts to deny or distort the history of the nation and the state's genesis."

- ^ Aybak 2016, p. 14.

- ^ Akçam 2012, p. xi.

- ^ Hofmann, Tessa (2016). "Open Wounds: Armenians, Turks, and a Century of Genocide by Vicken Cheterian". Histoire sociale/Social history. 49 (100): 662–664. doi:10.1353/his.2016.0046. S2CID 152278362.

The foundation of the Turkish republic and the CUP's genocide perpetrators are to this day commemorated with pride. Mosques, schools and kindergartens, boulevards and public squares in Turkey continue to bear the name of high ranking perpetrators.

- ^ Kieser 2018, p. xii. "[Talat Pasha's] legacy is present in powerful patterns of government and political thought, as well as in the name of many streets, schools, and mosques dedicated to him in and outside Turkey... In the eyes of his admirers in Turkey today, and throughout the twentieth century, he was a great statesman, skillful revolutionary, and farsighted founding father..."

- ^ Avedian 2012, p. 816. "Talaat and Cemal, both sentenced to the death in absentia for their key involvement in the Armenian massacres and war crimes, were given posthumous state burials in Turkey, and were elevated to the rank of national heroes."

- ^ Zürcher 2011, p. 316. "Many of the people in central positions of power (Şükrü Kaya, Kazım Özalp, Abdülhalik Renda, Kılıç Ali) had been personally involved in the massacres, but besides that, the ruling elite as a whole depended on a coalition with provincial notables, landlords, and tribal chiefs, who had profited immensely from the departure of the Armenians and the Greeks. It was what Fatma Müge Göçek has called an unspoken "devil's bargain." A serious attempt to distance the republic from the genocide could have destabilized the ruling coalition on which the state depended for its stability."

- ^ Gürpınar 2013, p. 420. "...the official narrative on the Armenian massacres constituted one of the principal pillars of the regime of truth of the Turkish state. Culpability for these massacres would incur enormous moral liability; tarnish the self-styled claim to national innocence, benevolence and self-reputation of the Turkish state and the Turkish people; and blemish the course of Turkish history. Apparently, this would also be tantamount to casting doubt on the credibility of the foundational axioms of Kemalism and the Turkish nation-state."

- ^ Üngör & Polatel 2011, p. 80.

- ^ Ungor, U. U. (2008). Seeing like a nation-state: Young Turk social engineering in Eastern Turkey, 1913–50. Journal of Genocide Research, 10(1), 15–39.

- ^ Schleifer, Yigal (2005-12-16). "Freedom-of-Expression Court Cases in Turkey Could Hamper Ankara's EU Membership Bid". Archived from the original on 21 February 2006. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Akçam, Taner (2012). The Young Turks' Crime against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15333-9.

- Aybak, Tunç (2016). "Geopolitics of Denial: Turkish State's 'Armenian Problem'" (PDF). Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies. 18 (2): 125–144. doi:10.1080/19448953.2016.1141582. S2CID 147690827. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-07-20. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- Atılgan, Mehmet; Eren, Onat; Mildanoğlu, Nora; Polatel, Mehmet (2012). 2012 Beyannamesi: İstanbul Ermeni vakıflarının el konan mülkleri (in Turkish). Uluslararası Hrant Dink Vakfı Yayınları. ISBN 9786058657007.

- Avedian, Vahagn (2012). "State Identity, Continuity, and Responsibility: The Ottoman Empire, the Republic of Turkey and the Armenian Genocide". European Journal of International Law. 23 (3): 797–820. doi:10.1093/ejil/chs056.

- Baghdjian, Kevork K. (2010). A.B. Gureghian (ed.). The Confiscation of Armenian properties by the Turkish Government Said to be Abandoned. Printing House of the Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia. ISBN 978-9953-0-1702-0.

- Bloxham, Donald (2005). The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-922688-7.

- Dadrian, Vahakn N. (2003). "The Signal Facts Surrounding the Armenian Genocide and the Turkish Denial Syndrome". Journal of Genocide Research. 5 (2): 269–279. doi:10.1080/14623520305671. S2CID 71289389.

- Dadrian, Vahakn N.; Akçam, Taner (2011). Judgment at Istanbul: The Armenian Genocide Trials. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-0-85745-286-3.

- Dixon, Jennifer M. (2010). "Education and National Narratives: Changing Representations of the Armenian Genocide in History Textbooks in Turkey". International Journal for Education Law and Policy. 2010 Special Issue: 103–126. Archived from the original on 2021-03-04. Retrieved 2023-02-27.

- Ekmekçioğlu, Lerna (2016). Recovering Armenia: The Limits of Belonging in Post-Genocide Turkey. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-9706-1.

- Göçek, Fatma Müge (2015). Denial of Violence: Ottoman Past, Turkish Present and Collective Violence Against the Armenians, 1789–2009. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-933420-9.

- Gürpınar, Doğan (2013). "Historical Revisionism vs. Conspiracy Theories: Transformations of Turkish Historical Scholarship and Conspiracy Theories as a Constitutive Element in Transforming Turkish Nationalism". Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies. 15 (4): 412–433. doi:10.1080/19448953.2013.844588. S2CID 145016215.

- Ihrig, Stefan (2016). Justifying Genocide: Germany and the Armenians from Bismarck to Hitler. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-50479-0.

- Kaligian, Dikran (2014). "Anatomy of Denial: Manipulating Sources and Manufacturing a Rebellion". Genocide Studies International. 8 (2): 208–223. doi:10.3138/gsi.8.2.06. S2CID 154744150.

- Kévorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85771-930-0.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2018). Talaat Pasha: Father of Modern Turkey, Architect of Genocide. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-8963-1.

- Oran, Baskın (2006). Türkiye'de azınlıklar: kavramlar, teori, Lozan, iç mevzuat, içtihat, uygulama (in Turkish) (3rd ed.). İstanbul: İletişim. ISBN 978-975-05-0299-6.

- Peroomian, Rubina (2008). And those who continued living in Turkey after 1915: the metamorphosis of the post-genocide Armenian identity as reflected in artistic literature. Yerevan: Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute. ISBN 978-99941-963-2-6.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (2009). "Truth in Telling: Reconciling Realities in the Genocide of the Ottoman Armenians". The American Historical Review. 114 (4): 930–946. doi:10.1086/ahr.114.4.930.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (2015). "They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else": A History of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6558-1.

- Üngör, Uğur Ümit; Polatel, Mehmet (2011). Confiscation and destruction: The Young Turk Seizure of Armenian Property. New York: e Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4411-3578-0.

- Zürcher, Erik Jan (2011). "Renewal and Silence: Postwar Unionist and Kemalist Rhetoric on the Armenian Genocide". In Suny, Ronald Grigor; Göçek, Fatma Müge; Naimark, Norman M. (eds.). A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 306–316. ISBN 978-0-19-979276-4.