Anthony Preston Smith

Anthony Preston Smith | |

|---|---|

| Born | January 6, 1812 |

| Died | August 17, 1877 (aged 65) |

| Resting place | Sacramento Historic City Cemetery |

| Occupation | horticulturalist |

| Known for | Smith's Pomological Gardens and Nursery |

Anthony Preston Smith (1812–1877), known as A.P. Smith, was a prominent horticulturalist best known for establishing Smith's Pomological Gardens and Nursery (commonly Smith's Gardens) in Sacramento, California.[1] The gardens were famous throughout California as a botanical wonder, introduced many new plant species to the state, and demonstrated the potential for horticulture, agriculture, and viticulture in the West.[1][2][3][4]

The gardens were destroyed by floods in the 1860s and 1870s. Looking back in 1881, the Sacramento Bee remarked that the gardens had been "to Sacramento what Golden Gate Park of recent years has been to San Francisco."[5]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Smith was born on January 6, 1812, in Rome, New York, the fifth of eight children of Anthony Smith (1778–1853), a farmer, and Paulina Preston (1781–1845).[6][7][8] In 1816, the family moved to Whiting, Vermont.[8] Smith's older brother, Sidney, was a partner in a dry-goods company in Troy, New York, and hired Smith as a clerk in 1835.[8]

In the early 1840s, Smith quit his brother’s firm to open his own horticulture farm. Among other things, Smith grew silkworm mulberry trees and experimented with silk farming.[8] While silk farming was on the decline,[9] the California gold rush was beginning.

In 1849, Smith partnered with 29 other men to purchase a barque, the William Ivy, and mining supplies.[8] They left from Boston, sailed "around the Horn," and arrived in San Francisco on July 7, 1849.[10] After trading and gambling during the 157-day voyage, Smith and five others had by then acquired full ownership of the ship and cargo.[8]

Smith’s Gardens

[edit]

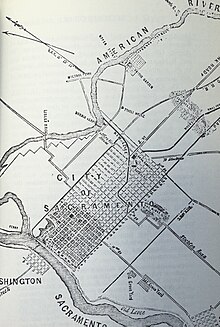

In December 1849, the partnership of A.P. Smith, M.A. Baker, and J.S. Barber, "nurserymen and gardeners," paid John Augustus Sutter Jr. $100 per acre for 50 acres of land on the south bank of the American River, about three miles east of Sutter's Fort.[8]

Smith immediately began improving the land, building a residence overlooking the river and planting gardens. Historian William Willis wrote in 1913, "As fast as [Smith] was able, he imported choice varieties of fruit and shade trees, ornamental shrubbery and plants."[6] Within a year, Smith was supplying vegetables and seeds to the burgeoning Sacramento market.[11][3] By 1852, a greenhouse and nursery were producing flowers, shrubs, and trees for transplanting, and Smith had started a peach orchard.[12][13][14] By then, the property was known as "Smith's Garden," though Smith marketed the project with the more scientific-sounding "Smith's Pomological Gardens and Nursery"---and it was truly a project of experimentation and scientific method.[12] Smith and his managers tested new plant species to find which could thrive outdoors in Sacramento's climate, and experimented with innovative irrigation, transplanting, grafting, and propagation techniques.

In 1853, Smith returned home to Vermont and persuaded his brother Sidney to return to Sacramento with him.[7] Sidney helped his brother operate a retail store in Sacramento at 40 J Street, which sold produce, seeds, and plants from the gardens.[5] Two of Smith's younger sisters, Tinnie and Carrie, also eventually moved into the garden residence.[7] One of his sisters taught at a nearby private school.

In 1854, Smith installed an impressive new irrigation system, drawing water from the American River with a ten-horsepower steam engine pump into a 7,000-gallon reservoir 16 feet above the gardens and then distributing the water throughout the 50-acre property. Smith's pump was more powerful than Sacramento’s main pump for the city reservoir.[15]

The State Agricultural Society, created in 1852, sponsored the first State Fairs beginning in 1854. Smith was a regular at the annual fairs, frequently exhibiting new products and earning top prizes, even toward the end of his life.[16] Smith was later elected an officer in the State Agricultural Society.[17]

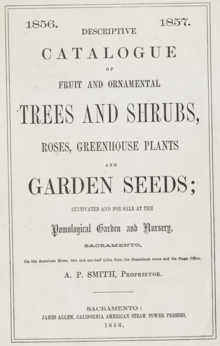

In 1856, Smith began publishing an annual catalog of his commercial offerings: Descriptive Catalogue of Fruit and Ornamental Trees and Shrubs, Roses, Greenhouse Plans, and Garden Seeds; Cultivated and for Sale at the Pomological Garden and Nursery, Sacramento. The catalog contained an introduction providing detailed best practices for customers and listed hundreds of different products from a stock of thousands of plants.[18] These offerings were the most extensive available on the West Coast.[19] Modern horticulture and viniculture experts are amazed at the vast number of varieties he had already imported in the 1850s and credit Smith for making important contributions to Sacramento’s leadership in the propagation of hardwood trees, roses, camellias, and grapes.[20][21][22][23]

In 1860, Smith presciently predicted, "wine is soon to become the first great staple of California, and ... our valley, together with the foot hills, [is] peculiarly adapted to the culture and rapid growth of the grape."[13]

Smith established specialized departments run by experienced professionals, employing many men in each department. James B. Saul managed the fruit and seed departments. William O’Brien managed the flower gardens and greenhouse.[15] Julius Pitois from Burgundy, France, managed the wine production.[13]

Smith opened the gardens to the public, hosted community events, and frequently invited guests to stay the night. Historian Winfield Davis writes, "No expense was spared in its adornment," and the gardens became a resort destination. The Southern Pacific Railroad and omnibuses (horse-drawn carriages) competed to ferry visitors to and from the gardens. Smith laid out hay and watered the roads to the gardens to minimize the dust for visitors. Shade trees lined the entrance to the gardens and cottage residence, which had a "pleasant suite of reception rooms." Smith laid out two miles of walking paths around the gardens, constructed with crushed sea shells he hauled upriver from San Francisco by schooner.[6][14]

The Sacramento Daily Union reported that "language cannot do justice to these grounds,"[13] but in 1860 the traveling poet Bayard Taylor tried:[24]

I must not leave Sacramento without speaking of the garden and nursery of Mr. A.P. Smith ... Our visit there was the crowning and culminating point of a glorious ride over the plain around the city...

An avenue, lined with locusts and arbor vitae, conducted us finally to a neat wooden cottage, the verandas of which were overrun with scarlet-fruited passionflowers. A clean gravel road enclosed a circle of turf, in the center of which grew willow, locust, and pomegranate trees, beyond which extended a wilderness of splendid bloom. Behind the house rose the fringe of massive timber that lines the American Fork. A series of stairs and balcony-terraces connected one cottage with another, forming an easy ascent to the very rooftops. A wild grapevine, which had so covered an evergreen oak that it resembled a colossal fountain pouring forth volumes of Bacchic leaves, stretched its arms from the topmost boughs, grasped the balconies, and ran riot up and down the roof, waving its tendrils above the chimneys.

Behind this Titanic bower were thickets of bay and willow, with a glimpse of the orange-colored river framed on the opposite side by a grand and savage setting. From the rooftop, the eye overlooked the whole glorious garden, the spires of the city, the yellow plain vanishing into purple haze, and the range of violet mountains in the east.

I was curious to see what had been done to introduce the trees and plants of other parts of the world into a climate so favorable to all, from Egypt to Norway. I found even more than I had anticipated. There, side by side, in the open air, grew natives of Mexico, Australia, the Cape of Good Hope, the Himalayas, Syria, Italy, and Spain. The plants were mostly very young, as sufficient time had not elapsed since the seeds were procured for them to reach full development, but their growth was all that could be desired. To my great delight, I found not only the Indian deodar and the funeral cypress of China but the cedar of Lebanon and the columnar cypress of Italy and the Orient. The exquisite Cape ericas and azaleas flourished as in their native air; the threadlike tamarisk of Africa, the Indian-rubber tree, the Australian eucalyptus, and the Japanese camellia were as lush and luxuriant as if rejoicing in their new home. In the conservatories, no artificial heat was required except for orchids and other tender tropical plants. What a spectacle of botanical splendor California will present fifty years from now! I would almost be content to live that long just to behold it.

Not less remarkable was the superior luxuriance shown by plants from the Atlantic States when transferred to the Pacific. The locust, especially, doubles the size of its leaves, and its pinnated tufts rival those of the sago palm. The paulownia spreads a tremendous shield, and even the evergreens, especially the thuya, manifest a new vitality. Roses grow so large that they suggest peonies yet lose none of their fragrance or beauty. I never beheld a more exquisite bouquet of half-blown roses than the one Mr. Smith’s gardener cut for my companion. Great beds of wistaria, heliotrope, and mignonette ran wild like weeds, while lemon verbena grew into bushes taller than our heads. The breezes, heavy with excess of perfume, flowed languidly through the garden, creating an atmosphere that could only be compared to the nutmeg orchards of Ceylon.

The property rapidly increased in value. In 1855, Smith declined an offer of $75,000.[8] By 1859, the orchard production alone was grossing more than $70,000 per year.[19]

Floods and Bankruptcy

[edit]Early Sacramento was repeatedly flooded in the late 1800s. Rain and snowmelt in 1861 and 1862 overwhelmed the levee on the American River and flooded most of Sacramento for weeks. Smith’s gardens were devastated. His residence and many work sheds were swept away. About 500 feet of land along the riverbank of the gardens was undercut and washed away. One to six feet of sand and mud covered the gardens. Nearly all fruit trees were killed.[6]

The flood ruined Smith financially. Smith had just obtained a $10,000 mortgage in 1859.[25] Beginning in 1862, his creditors began foreclosing on his salvageable property.[26] Smith was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1863. He remained on the property, but for several years his production continued to be sold by his creditors. [27]

A dispute between his creditors led to a landmark California Supreme Court decision: Robinson v. Russell (1864) 24 Cal. 467. The court held that, while trees are normally considered part of real estate and an interest of a mortgagee of the land, Smith's trees were grown as an agricultural product with the intention of being extracted and sold. Therefore, the sheriff was able to dig up and sell Smith’s trees through execution to satisfy the claims of priority creditors of Smith’s business.

Smith worked to restore the gardens in the 1860s and nearly succeeded.[28] After 1862, when levee reconstruction plans were being adopted, Smith made strenuous efforts for the levee to protect his property, but he failed.[6] Then another devastating flood in 1871–72 washed everything away again.[6][14]

An 1880 lawsuit alleged that upstream hydraulic mining was partially responsible for 1861-62 flooding by filling the river with accumulating sand and mud. Smith’s gardens were considered 'high ground' when his partnership purchased the land in 1849. Smith had complained about sand accumulation around his pump in the 1850s. Sidney testified at the 1880 trial.[29]

Later life

[edit]Smith continued to innovate throughout his life. Even after the 1861–62 floods, he continued to exhibit new varieties of fruits, vegetables, and flowers and showed pigs at the state fairs; experimented with silk farming; negotiated a contract to export fruit to China[30]; and even patented an innovation in ladders.[31]

In the 1860s, Smith led an effort to create the American River School District.[32]

After being sick for several months, Smith died on August 17, 1877.[1] He was buried in the Pioneer Grove section of the Sacramento Historic City Cemetery.[33]

Legacy

[edit]When Smith died, his once-glorious gardens had diminished to a small, run-down fruit farm. Smith is now mostly forgotten. His gardens are gone without any historical marker, and he has no eponyms remembering him. In 1958, the Sacramento County Historical Society observed, "even the memory of this local bit of arcadia soon faded into oblivion for all but a few local antiquarians."[14]

In the 1940s, Smith's former property was annexed by the City of Sacramento and developed as the River Park neighborhood by oilman John Sandburg and developer Louis Carlson. Sandburg and Carlson named most of the streets in River Park after themselves, their family, friends, and business associates. No street names, plaques, or monuments commemorate Smith, although the neighborhood has many fruit trees, camellias, roses, and, fittingly, a garden club.[34]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Another Pioneer Gone". Sacramento Bee. 17 August 1877. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ "A Fruitful Garden". Los Angeles Star. 20 June 1857. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

...the famous Smith Gardens...

- ^ a b Morrison, A.E. (11 May 1935). "Agricultural History of County is Traced From Time of Indians". Sacramento Bee. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ "Sacramento Was Site of State's First Nursery". Sacramento Bee. 21 October 1950. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ a b "Sidney Smith - Death of an Aged Citizen Yesterday". Sacramento Bee. 21 November 1891. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Willis, William Ladd (1913). History of Sacramento County, California. Historic Record Company.

- ^ a b c Records of the Families of California Pioneers (Vol. II) (PDF). Daughters of the American Revolution. p. 345.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Davis, Winfield J. (1890). An illustrated History of Sacramento County, California. Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co. p. 473-74. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ Landry, David. "History of Silk Production". Mansfield Historical Society. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ "Marine Journal - Port of San Francisco". Weekly Alta California. 12 July 1849. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ Morrison, A.E. (1932-02-03). "Seven Men One Time Owned All County's Farms". Sacramento Bee. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ a b "Smith's Gardens - Beautiful Show of Camellias". California Farmer and Journal of Useful Sciences. 6 March 1857. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d "City Intelligence - Two Hours at Smith's". Sacramento Daily Union. 29 May 1860. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d Sacramento County Historical Society (October 1958). "Smith's Gardens, Sacramento's Showplace of a Century". Golden Notes. 5 (1). Sacramento Public Library, Sacramento Room.

- ^ a b "Fruit, &c". Sacramento Daily Union. 25 July 1856. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ "State Fair - Additional Awards of Premiums". Sacramento Bee. 30 September 1874. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

A.P. Smith: Step-ladder for picking fruit, special premium recommended

- ^ "State Agricultural Society". Sacramento Bee. 1 February 1861. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ Descriptive Catalogue of Fruit and Ornamental Trees and Shrubs, Roses, Greenhouse Plans, and Garden Seeds; Cultivated and for Sale at the Pomological Garden and Nursery, Sacramento. Sacramento: James Allen, California American Steam Power Presses. 1856. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ a b "Smith's Pomological Gardens". California Farmer and Journal of Useful Sciences. 2 December 1859. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ McPherson, E. Gregory; Luttinger, Nina (March 1998). "History of Sacramento's Urban Forest" (PDF). Journal of Arboriculture. 24 (2): 72. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ Christopher, Thomas (2002-05-01). In Search of Lost Roses. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226105962.

- ^ Pinney, Thomas (1989). A History of Wine in America. University of California Press. p. 264. ISBN 0520254295. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ Shepard, Iva Gard (8 March 1952). "Largest Capital Camellia Show This Weekend Marks Tree's Centennial". Sacramento Bee. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ Taylor, Bayard (15 March 1860). "Pictures of California - Ten Years Later". Sacramento Bee. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ "Robinson v. Russell (1864)". Casetext. California Supreme Court. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ "Sheriff's Sale, California Wines". Sacramento Bee. 9 October 1862. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ "G.L. Suydam & Co., Successors to A.P. Smith & Co". Sacramento Bee. 3 January 1863. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ "Smith's Pomological Gardens". Sacramento Bee. 16 May 1863. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ "Gold Run Case". Sacramento Bee. 19 November 1881. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ "For China". Sacramento Bee. 16 May 1870. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ "Improvement in ladders". Google Patents. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ "Supervisors, Yesterday". Sacramento Bee. 8 January 1869. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ "Database Project". Sacramento Historic City Cemetery. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ Vincent, Richard (April 2020). "RP History Corner" (PDF). River Park Review. 20 (2): 5. Retrieved 27 January 2025.