Anne Azgapetian

Anne Azgapetian (May 26, 1888 — September 1, 1973), also seen as Ann Azgapetian and later as Anne Heald or Aya Heald, was a Red Cross worker during World War I, and a lecturer and fundraiser after the war, and a writer. She was born in Russia, married an Armenian general, and lived in the United States most of her life.

Early life

[edit]Anne Azgapetian was born in Grodno, now part of Belarus.[1] She moved to the United States with her family, and attended school in Indianapolis, Indiana.[2] She was naturalized as a United States citizen in 1893. She sometimes identified herself as Lithuanian.[3] In 1915, she married diplomat Mesrop Nevton Azgapetian, also a naturalized American citizen; he was born in Istanbul and educated at Columbia University. Soon they left New York for World War I.[4]

War work

[edit]Anne Azgapetian worked as a Russian Red Cross nurse in the war, through pregnancy and the birth of her daughter in 1916.[5][6] She witnessed thousands of war orphans finding safety and food in American refugee camps run by Near East Relief.[7] She was awarded the Medal of St. Stanislaus in Russia, and a gold medal from the Shah of Persia, in recognition of her contributions.[3]

Lecture tour in the United States

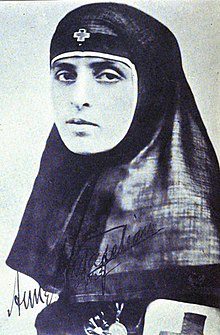

[edit]Azgapetian made an extended lecture tour of the United States beginning with her husband in 1918,[3] raising funds for postwar relief.[8][9] "Lady Ann Azgapetian, little woman, dressed in gray, wearing on her head the veil of the Red Cross madonna, and carrying on her waist decorations in ribbon and bronze, stands before us," as one American report described her appearance in 1922.[7] She spoke to churches,[10] women's organizations, and professional and political conventions, including the National Education Association[11] and the National Woman's Party.[12] She also participated in pageants and parades in the cause of Armenian war relief.[13]

Writings

[edit]Azgapetian wrote at least four plays: In 1930, she wrote a three-act play, Commandments.[14] She wrote two plays under the name "Anne Azgapetian Heald": the one-act Ravenduz (1960) and another three-act drama, The Eleventh Commandment.[15] Under the name "Aya Heald"[16] she wrote another play, What Reward? (1954),[17] and a novel, Shadows Under Whiteface (1956).[18]

Later life

[edit]Anne Azgapetian and her family stayed in the United States after 1918. Her husband died in 1924, leaving her a widow with two young children.[19] She sold Armenian handicrafts to raise money, in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1925[20] and in Palm Beach, Florida, in 1926.[21] She moved to Lake Placid, New York, in the mid-1920s, and was described as "an experienced actress" in addition to her other pursuits.[16]

Anne Azgapetian married again, to Willis Heald, after 1930. She died in 1973, aged 85 years.[22] Her daughter Araxie Azgapetian Dunn (1916-2012) was a businesswoman in Lake Placid, New York.[23] Her son Ahzat Victor Azgapetian (1919-1978) was a scientist involved in the space industry.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ Victoria Martínez, "Faces of Diversity in American First-Wave Feminism" A Bit of History (November 7, 2018).

- ^ "Noblewoman to Visit Richmond" Richmond Item (June 1, 1921): 2. via Newspapers.com

- ^ a b c "To Speak for Near East Relief Fund" Baltimore Sun (January 24, 1919): 4. via Newspapers.com

- ^ "Don't Fail to Hear Noted Speaker" Wellsboro Agitator (May 11, 1921): 1. via Newspapers.com

- ^ "Gamma Phi Beta's Share in Near East Relief" The Crescent of Gamma Phi Beta (March 1922): 178-183.

- ^ "Gives Armenia's Thanks for U. S. Relief" Los Angeles Herald (January 22, 1920): B-15. via California Digital Newspaper Collection

- ^ a b F. K. S., "Listening In: Cross Versus Crescent" The Epworth Herald (May 20, 1922): 492.

- ^ "The Story of Armenia Brings Unusual Gifts" The New Near East (June 1921): 7.

- ^ "B. O. Receipts for N. E. R." The New Near East (October 1921): 16.

- ^ "Persian Princess Speaks in Church Wednesday Evening" Palladium-Item (May 31, 1921): 4. via Newspapers.com

- ^ Proceedings (National Education Association 1922): 1296-1297.

- ^ Photograph published in The Suffragist (Jan.-Feb. 1921): 343; now in the Records of the National Woman's Party, Library of Congress.

- ^ "Lady Azgapetian Arrives in Indianapolis to Aid Pageant" The Indianapolis News (August 29, 1922): 10. via Newspapers.com

- ^ Library of Congress, Copyright Office, Catalog of Copyright Entries (US Government Printing Office 1929): 379.

- ^ Library of Congress, Copyright Office, Catalog of Copyright Entries (US Government Printing Office 1967): 13.

- ^ a b Hudson Tanner, "Placid Mirror" Adirondack Daily Enterprise (February 13, 1956): 2. via NewspaperArchive.com

- ^ Library of Congress, Copyright Office, Catalog of Copyright Entries (US Government Printing Office 1954): 116.

- ^ "Murder Story at Whiteface" The Post-Standard (April 22, 1956): 36. via Newspapers.com

- ^ Untitled brief news item, The News-Herald (May 16, 1925): 13. via Newspapers.com

- ^ Advertisement, Poughkeepsie Eagle-News (May 11, 1925): 3. via Newspapers.com

- ^ Advertisement, Palm Beach Post (January 22, 1926): 29. via Newspapers.com

- ^ "United States Social Security Death Index"" database, FamilySearch, U.S. Social Security Administration, Death Master File, database (Alexandria, Virginia: National Technical Information Service).

- ^ "Araxie Dunn" Lake Placid News (March 30, 2012).

- ^ "Computers May Hire, Fire Personnel in Near Future, Expert Predicts" Los Angeles Times (October 21, 1965): 176. via Newspapers.com

External links

[edit]- A grandchild of Anne Azgapetian maintains a family history website, Azgapetian.org Archived 2021-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, with many photographs of Lady Anne and other relatives.