3, Triq ix-Xatt

| 3, Marina Street, Marsaskala | |

|---|---|

3, Triq Ix-Xatt, Marsaskala | |

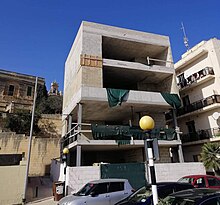

The building in 2017 | |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | Demolished |

| Type | Summer house |

| Architectural style | Vernacular |

| Location | Marsaskala, Malta |

| Address | 3, Triq Ix-Xatt |

| Coordinates | 35°51′53.0″N 14°33′44.5″E / 35.864722°N 14.562361°E |

| Current tenants | Redeveloped |

| Completed | 19th century |

| Owner | Stivala Group |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Limestone |

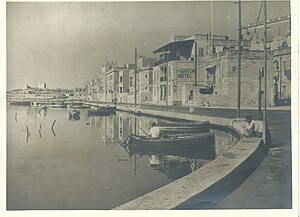

3, Triq ix-Xatt was a nineteenth-century building in Marsaskala, Malta. Built during the Crown Colony of Malta, it was a vernacular structure which appears in an iconic 1885 photo of the former fishing village - prior development into a residential and holiday location. It was among the few old buildings in the area at one time, which at some point became a residence until it became vacant.

Being at one side in a development zone and on another side in a conservation area made the latter irrelevant, according to some Planning Authority (PA) regulations. It thus became subjected to demolition and re-development, and the Superintendence for Cultural Property found no objection by claiming that it has vernacular characteristics with no detailed design.

The initial observation and decisions taken by the PA and the Superintendence have received waves of criticism to demolish the building, to replace it with another double purpose building - with NGOs, the local council, residents and parties spreading out information and opposition about the development. The building was demolished gradually in 2018.

Background

[edit]The location where the building existed until 2018 was originally a fishing village but gradually developed into a crowded building zone, as a holiday destination for locals and foreigners as well as permanent residence to others.[1] It was inhabited since pre-history and was a Roman port in antiquity.[2][3] Throughout Maltese history Marsaskala was prone to barbary attacks from the sea and was not safe to live and prosper. The nearby then villages, and later cities, of Żejtun and Żabbar were subject to similar landings from sea.[4]

Buildings erected in the area and in the immediate vicinity were generally fortified. A number of coastal defence structures were built in different centuries. Thus there was minimum interest to develop a community until well in the 19th century, with the exception of few farmhouses, when the course of events and situation in the Mediterranean Sea has changed drastically.[5]

History

[edit]Context

[edit]

According to Louis de Boisgelin (historian of the Order of St John), in 1805 there was nothing notable as for urban development in Marsaskala, apart from the port which was evidently used as a harbour.[6] By 10 March 1854, fishing in the zone required permission with respect to certain conditions.[7] Since the 1950s,[8] electricity also became available for private property at the request of the owners.[9] In 1969 it was observed that there was the first building boom in the area.[10] By the 1970s, sewage system was installed for most of the buildings of Marsaskala.[11]

The surrounding land remained mostly arable with traditional terraced fields at the backdrop of the summer residences until the 20th century, when permissions was granted to build apartment dwellings.[12] People from the Cottonera had built a number of summer residences in Marsaskala, also because in the 19th century the area was under the parish of Senglea. Marsaskala became a vice-parish of Żabbar by the early 20th century.[13] Another part of Marsaskala was part of Żejtun.[14]

In the 20th century, the area where the building stands saw a massive transformation. A government census taken on 26 April 1931 found a good number of habitable houses of the time were vacant throughout the year.[15] During WWII the few residents of the village were evacuated, leaving only the presence of the British military.[16] On 19 March 1949, Marsaskala was declared a parish of its own, when the villagers did not just return but there was also an increase in population.[17] In 1963 it was noted that most houses in Marsaskala were next to the sea, with the main reason being to enjoy the breeze in warm weather.[18]

The town experienced another significant change in 1982, from a rural and fishing village to a major tourist destination,[12] in which period was experiencing a "Villscape in transition".[19] the Jerma Palace Hotel was opened in the locality which led to a consequentialism further development; this has resulted in the change of use of the area, and sea activity took a minor role since the 1980s.[12][20] The hotel closed down in 2007 and other alternatives were sought by the Marsaskala Local Council to regenerate the area. The council has noted that cultural heritage was the prime reason for foreigners to visit the area but at the same time it was not being preserved.[21]

A number of building blocks, in the vicinity of Triq ix-Xatt and close to sea, were deemed an eyesore and unsustainable to the village in 2010.[22] This and other formalized the question whether Marsaskala has adopted Bugibbisation, which happens when a large concentration of buildings overshadow the characteristics of a traditional Maltese village.[12] Most traditional old houses in Marsaskala have been destroyed and replaced with economical accommodation for the growing demand of the population; this has led a rapid destruction of much of the heritage of Marsaskala, of which since the 21st century the urban area barely portrays what used to be a fishing village.[23] A proposed regeneration for Marsaskala in 2008 supported the idea of a "Transit Village" with a hybrid transformation.[24]

Area

[edit]

The first group of houses in Marsaskala were constructed around the mid-19th century, during the Crown Colony of Malta, and some were built to be used for the primary sector such as fishing, but also for leisure. Other working activities involved farming and collecting salt from pans at the sea shore.[12] The most prominent buildings were those next to the shore. Some of these houses were used almost only for summer.[25] These houses were generally small with plenty of space in front and behind.[26]

In the 1970s several British people lived in the proximity of the building and a road, Triq ix-Xatt, in front of the building was constructed partially by land reclamation to accommodate more access to traffic and pedestrians.[27] At this point, the first wave of food stores and restaurants catered for the population who lived there and its visitors.[9] Several of the early buildings in Triq ix-Xatt were not spared from modifications to accommodate restaurants, cafeterias and take-aways.[12] At this point, a natural sandy beach in Triq ix-Xatt was lost forever as it has become too spoilt to dare to swim.[12] Some of the cultural buildings in Triq ix-Xatt were demolished or partially demolished for similar reasons, as this made well for greater income to the developers.[22]

In the 1990s, the remaining empty land on one side of the building was developed with the erection of the Brighton Hotel. The place became much frequented because of the Brighton Pizzeria; this also has since made an impact in the whereabouts of the building because of the litter the clients left.[12][28] Some of the traditional houses in the street were demolished and replaced by modern buildings, described as being mediocre in terms of architecture and aesthetic design.[29]

Building

[edit]

The building at 3, Triq ix-Xatt (Marina Street),[30][31] Marsaskala, was located between the front of scheduled Villa Apap Bologna with its adjoint chapel and the main promenade of the village.[32] It was built sometimes in the 19th century but its exact date and other details are unknown.[32] The Planning Authority was requested by the Local Council and others to make a study about the details of the building but these were not carried out.[32] It is established that the building appeared on site since the earliest and all photos know of the site.[33] The first photo taken of the area, showing the building, is in a nostalgic photograph of 1885.[34] It is generally described as of being vernacular architecture, meaning it may had no architect or general planning.[35] The latter implies that it was built for convenience to the owners for specific purpose close to the sea.[36] It is known to have been one of the few early sea-side houses.[37] It has been described as one of the oldest residential properties in Marsaskala.[32][38][39][40] It was entirely located within the Urban Conservation Area (UCA).[32] It originally had wooden apertures and a prominent balcony looking towards the sea.[41]

Until more buildings became on demand and some roads were required to be constructed, patrons of summer houses freely walked from their doorsteps on natural coast formation to the sea for a swim.[42]

In the late 2010s the residence was sold and left vacant by the new patron. The building was left to dilapidate and without maintenance, but remained intact.[32][43][44][45][46][47][48]

A document of the Planning Authority, dated July 2006, includes the site in the Entertainment Priority Area.[49] The Local Council installed rustic designed electric lamps in 2010 in the centre of the village, and this included one lamp attached on the building as it is in the immediate vicinity.[50] The lamps were noted by the Planning Authority in 2016.[51]

The site is detached from other building, with four streets surrounding it. The four streets are Triq ix-Xatt, It-Tieni Trejqa, Triq Sant’ Anna and It-Tielet Trejqa.[52][53] Having four corners, it had the sight of two principals roads from two balconies, with one wide balcony at the front and a smaller one at the back. It had a number of apertures, some of which were walled up over the years, with the remaining apertures having modern black aluminium frames, which replaced other apertures. Similar to other early buildings, it had a wide front terrace, looking towards the sea, where the main entrance stood.[54]

The 19th-century building was originally part of number of old buildings within the Conservation Area of Marsaskala.[55] The building was adequate to be embellished for different use, including a restaurant.[41][56] The building is found in an area of high economic income for development, at the seaside of Marsaskala where a chain of restaurants operate. It thus had become profitable to develop the site. Even if so, the decision was regretted by conservationists and locals as this led to the loss of another vernacular structure.[56]

Application

[edit]| External image | |

|---|---|

Architect

[edit]The Planning Authority has received an application (PA/02240/17) from Architect Christopher "Chris" Mintoff, on behalf of developer Michael Stivala, for the complete demolition of the building at 3, Triq ix-Xatt, and to be replaced by another higher structure.[57] The new building is proposed to cater for a restaurant, with a residence on the top floors having a separate entrance.[53]

At the time of the application, Mintoff was the President of the Chamber of Architects (Maltese: Kamra tal-Periti) of Malta.[58] He has criticised the Planning Authority for its weak and nonsense policies over its development decisions, saying it goes as far as issuing permits against building regulations and having its functioning operating in a "bureaucratic mess".[59] As of 2019 Mintoff is no longer the President of the Chamber of Architects, and has continued to constructively criticise demolition and development policies.[60]

Developer

[edit]The developer, Michael Stivala, is the chairperson of Stivala Group.[61] He is also the General-Secretariat of the Malta Developers’ Association (MDA),[62] and simultaneously a member of the council of the Malta Hotels and Restaurants Association (MHRA).[63] He is known for his lobbying for further construction, with the Government of Malta and the Planning Authority.[64] Stivala is a construction and hospitality co-developer with his other family members. One of the branches of his shared ST Group company is the ST Properties Ltd which focuses on mixed-use development. The group claims to invest in economical sustainable development which yields good income.[65] Stivala (August 2018) has criticised environmentalists and supportive politicians for their agenda against overdevelopment, and in response to this John Consiglio (August 2018) has rebutted him by saying that he is a main contributor for the "Uglification of Malta".[64]

Planning Authority

[edit]| Application | PA/02240/17 (Full Development) |

|---|---|

| Applicant | Michael Stivala (o.b.o. Stivala Group) |

| Architect | Christopher Mintoff |

| Notice | Yes (On Site and Government Gazette) |

| Case Officer | Roderick Livori |

| Endorsement | Robert Vella |

| Objectors | Yes (Local Council, NGOs, Public, ..) |

| Decision | Approved |

As per law, the application was sent by an Architect, Christopher Mintoff, on behalf of Stivala, and it was received on October 4, 2016.[57] The application was left pending while studies were underway and was considered as a valid application on March 27, 2017.[57] During this time, the case officer inspects the place, sets meetings with the Architect and Developer, and informs about the results to pertinent authorities.[66]

It has been observed that the site falls within the Urban Conservation Area (UCA) and within the Development Zone.[57] A decision had to be taken before July 21, 2017, as a target date by the Case Officer Roderick Livori, who has a bachelor's degree in geography.[57] The proposed application was first published in the Malta Government Gazette on April 2, 2017, as a Legal Notice requirement, and appeals could be received until May 12, 2017.[57] The same Legal Notice was attached to the main façade of the building.[67]

Livori presented a draft report to Robert Vella, who on June 1 decided to endorse it.[57] The report was discussed with the commission or board during the agenda which took place in the same month on the 21st, which made the decision to grant the permission on the same day.[57] Another notice, non-executive, was available on July 20, 2017, and a final decision was taken in the same month on the 26th, with a decisive post on September 27, 2017.[57] The application was approved and works were given the go ahead from March 5, 2018.[57]

It is common for the Planning Authority to give permission for demolition when the bad practice of using cement, that makes the building deteriorates, takes place. This is a common option for developers in Malta to take for justifying demolition.[68]

Superintendence

[edit]

On 21 June 2017,[72] it was revealed that the Superintendence for Cultural Heritage (SCH) has not opposed the complete demolition and development.[73] The Superintendent Anthony Pace did not consider the building of having any heritage value, and this gave way for its demolition.[74]

Even so, opposition by the SCH is irrelevant as the 2016 Development and Planning Act allows the Planning Authority to ignore recommendations by the SCH.[75] This act, to ignore the SCH, has been used from the beginning of its creation. Other vernacular building, even of architectural and historic value, have been destroyed by permission of the Planning Authority.[68] In March 2018 it was announced, by Minister Owen Bonnici (Ministry for Justice, Culture and Local Government), that Pace will be terminating his position as a superintendent and the vacant role to be filled by Joe Magro Conti.[76]

Reactions

[edit]Marsaskala Local Council

[edit]In 2017, the Local Council has described the building of being a local and national heritage, irrelevant of the decision, and recommended the Planning Authority to review its decision.[32] The Council commented:[77]

Għaldaqstant, il-Kunsill Lokal ta’ Marsaskala se jieħu r-responsabbilta’ sabiex

jipprova jissalvagwardja din il-landmark li żgur li hija ta’ importanza għal

Patrimonju Kulturali mhux biss ta’ Marsaskala imma ta’ Malta kollha.

(Meanwhile, the Local Council of Marsaskala will take responsibility to

try to safeguard this landmark that is for sure of importance for

Cultural Patrimony not just for Marsaskala but for Malta at a whole)

The Local Council has filed to appeal of the proposal in June 2018, and on that day it planned to urgently meet on May 18, 2018.[32][78]

The Council initially opposed any change to the historic building, irrelevant to its condition.[79] The Councillor said that the Architect of the developer has misguided the Local Council by purposely allowing the prescription date for appeal of development to pass.[80]

The Local Council has discussed the application during a meeting when the public was able to attend and everything was broadcast live on the internet.[81][82] The Local Council was surprised with the decision of the Planning Authority case officer that gave the permission.[83]

NGOs

[edit]

Heritage NGOs, such as Din l-Art Ħelwa (National Trust of Malta) and Flimkien għal Ambjent Aħjar (Together for a Better Environment), have opposed the demolition of the building.[36][45] The NGOs believe that vernacular buildings, whether in urban development or in rural environment, should be preserved as a main Maltese characteristic in architectural heritage which generally gives character to a given village. The NGOs observed that such buildings are being demolished by developers and replaced by non-contextual buildings with a building style not traditional to Maltese built environment. The NGOs believe that, if the developers are willing, such a building could be preserved and converted into a number of possibilities such as accommodation in hospitality services and catering. The NGOs fear that not enough is being done to preserve vernacular architecture and when such buildings are demolished it changes the typical area where the building stood. The NGOs believe that the building in Marsaskala has contributed to the architectural development of the village.[56][84]

The executive president of Din l-Art Ħelwa, Maria Grazia Cassar, became a militant spokesperson against the demolition of vernacular buildings in rural and urban environment. She said that such buildings are pertinent to be retained. A meeting was set up by Din l-Art Ħelwa where the Prime Minister, Leader of the Opposition and other distinguished people were invited. The meeting took place right after the 2017 general election which was thought to be an ideal period to set mutual understandings. The NGO presented its views against the permissions lately given by the Planning Authority, but the response was a set-back for the organisation.[85]

Flimkien għal Ambjent Aħjar requested an investigation into the granting of the permission.[86]

Residents

[edit]People from Marsaskala opposed the demolition of the building, together with rejecting any replacement building, independent and irrelevant to the opinion of the superintendence. The main reason behind the objection by Marsaskala residents was to maintain the old building and restore it. Some official objections by individuals, numbering at least 18, were presented to the Planning Authority. Driven by the outrage of many other residents, the Marsaskala Local Council has shown opposition and supported similar views of the objectors.[43]

Media

[edit]More people were informed through the media and social network.[87] On April 26, 2017, the Malta Today revealed the planning application proposal. Journalist James Debono of Malta Today had reported the proposal and remained following all pertinent steps about the building.[32] On June 22, 2017, In-Nazzjon reported, on the front page, that the Planning Authority has approved the full application.[38]

Political views

[edit]Back in 2005, then Councillor of Marsaskala Owen Bonnici (later Minister for Justice, Culture and Local Government) has criticized the Nationalist Government for any development which changes the remaining characteristics of the fishing village.[88]

In May 2011, prior to the application, Carmel Cacopardo of Democratic Alternative has described Marsaskala as a "Concrete Jungle" saying that many houses have been replaced by unsympathetic buildings. According to public discussion online this happens because of political interventions that intervene to favour the developers with the entities responsible for building regulations.[89]

The Superintendent, Pace, was harshly criticized for his passive role and laissez-faire (let it be) attitude as superintendent by the Democratic Party.[90]

Decision

[edit]

Demolition

[edit]The proposed development was approved, without modifications from the original planning.[43][91]

Replacement

[edit]A modern contemporary building was approved by the Planning Authority with a visible modern twist.[32] The ground floor will be ideal for a busy two-floors restaurant, and capable of adapting to catering needs.[92] It will be one of a series of food and beverages places in Marsaskala.[10]

The top floor will have its own entrance leading to a maisonette.[92] The building will be higher than the older one, but not more than other buildings on the side. It will partially hide the landmark view of a scheduled villa at the back but the villa is considerably on an upper ground.[84][93] The building height of the street and the old core, according to local planning, is supposedly two floors[94] in Triq Sant Anna and three floors in Triq ix-Xatt.[95] However, several buildings along the street have more floors, at a maximum of four floors, and this put a legal challenge for the authorities to allow similar permissions.[55]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wilson 2000, p. 138

- ^ Evans 1971, p. 198

- ^ Atauz 2008, p. 354

- ^ Marsaskala Local Council 2014

- ^ My Guide Malta 2018

- ^ Kerdu 1805, p. 21

- ^ Proclamations 1853, pp. 28, 29

- ^ Cilia 2002, pp. 33, 34

- ^ a b Time & Tide 1971, p. 29

- ^ a b Balls 1969, pp. 76–78

- ^ National Gov. Pub. 1975, p. 96

- ^ a b c d e f g h Baldacchino 2013, p. 99

- ^ Attard 2017a, pp. 2–4

- ^ Zen 2009a

- ^ Government Census 1932, p. xxiii

- ^ Pullicino 2012, p. 92

- ^ Bonnici & Cassar 2004, p. 227

- ^ Rose 1963, p. 139

- ^ Young 1983, pp. 35–41

- ^ Independent 2016

- ^ Marsaskala Local Council 2012

- ^ a b Holden & Fennell 2013, p. 204

- ^ Vella 2017

- ^ Studio Malta 2008

- ^ Scerri

- ^ Restoration Directorate 2012

- ^ Vella 2014

- ^ Baldacchino 2013, p. 96

- ^ Debono 2017g, p. 6

- ^ Independent 2008

- ^ Dietrich 2010, p. 152

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Debono 2017c, p. 8

- ^ Mamo 2017

- ^ Zen 2009b

- ^ Cassar 2017a, pp. 10, 11

- ^ a b Cassar 2017b

- ^ Independent 2013

- ^ a b Attard 2017b, pp. 1–2

- ^ Borg 2017a

- ^ Borg 2017b

- ^ a b Independent 2017c, p. 9

- ^ Tayar 2000, pp. 51, 52

- ^ a b c Debono 2017b

- ^ Urpani 2017

- ^ a b Carabott 2017a

- ^ Independent 2017a

- ^ Debono 2017a

- ^ Net 2017

- ^ Mapping Unit 2006b, p. 1071

- ^ Marsaskala Local Council 2010

- ^ MEPA 2016

- ^ Planning Authority 2017b, p. 8874

- ^ Nelson 1978, p. 127

- ^ a b Sultana 2017, pp. 1–2

- ^ a b c Cassar 2017c

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Livori 2017

- ^ Vassallo 2015

- ^ Martin 2015

- ^ Mintoff 2019

- ^ Cassar 2017

- ^ Bonnici 2019

- ^ Debono 2014

- ^ a b Consiglio 2018

- ^ Stivala 2018

- ^ Martin 2017

- ^ PA 2017

- ^ a b Debono 2016

- ^ PA & MTA 2018, pp. 1–8

- ^ Mifsud 2017

- ^ MDA 2018

- ^ Board Minutes 2017, p. 1

- ^ Grech 2017b, pp. 1–10

- ^ Fenech 2017

- ^ Torpiano & Zammit 2019

- ^ Times 2018

- ^ One 2017

- ^ Carabott 2017c, p. 5

- ^ Grech 2017a, pp. 1–8

- ^ Grech 2017c, pp. 1–4

- ^ Grech 2017d, p. 1

- ^ Grech 2017e, p. 1

- ^ Times 2017

- ^ a b Grech 2017g

- ^ Cassar 2018, p. 2

- ^ TVM 2017

- ^ Net News 2017

- ^ Bonnici 2005

- ^ Cacopardo 2010

- ^ Independent 2017b

- ^ Malta Today 2017

- ^ a b Grech 2017f, pp. 1–6

- ^ Carabott 2017b

- ^ Mapping Unit 2006a, p. 1068

- ^ MEPA 2005

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- Atauz, Ayse Devrim (2008). Eight Thousand Years of Maltese Maritime History: Trade, Piracy, and Naval Warfare in the Central Mediterranean. University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813031798. OCLC 163594113.

- Baldacchino, Godfrey (2013). Global Tourism and Informal Labour Relations: The Small Scale Syndrome at Work. Routledge. ISBN 9781134730667.

- Balls, Bryan (1969). Traveller's Guide to Malta: A Concise Guide to the Mediterranean Islands of Malta, Gozo, and Comino (2nd ed.). T. Cox. ISBN 9780092082108. OCLC 123136362.

- Bonnici, Joseph; Cassar, Michael (2004). A Chronicle of Twentieth Century Malta. Book Distributors Limited. ISBN 9789990972276. OCLC 255311524.

- Evans, John Davies (1971). The prehistoric antiquities of the Maltese Islands: a survey. Athlone Press. ISBN 9780485110937. OCLC 161646.

- Government Census (1932). Census of the Maltese Islands, Taken. Valletta: Government Printer. OCLC 314900144.

- Proclamations (1853). Laws and Regulations of Police for the Island of Malta and Its Dependencies (in English and Italian). From the Library of Modern and Contemporary History, Rome: nella Stamperia di Governo, Malta.

- Holden, Andrew; Fennell, David A. (2013). The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and the Environment. Routledge. ISBN 9780415582070.

- Kerdu, Pierre Marie Louis de Boisgelin de (1805). Ancient and modern Malta, as also, the history of the knights of St. John of Jerusalem. From Oxford University.

- Nelson, Nina (1978). Malta. Batsford. ISBN 9780713409413. OCLC 4491231.

- Pullicino, Philo (2012). The Road to Rome. MPI Publishing. ISBN 9780954490638. OCLC 881062291.

- Rose, Harold (1963). Your guide to Malta. A. Redman. OCLC 252434434.

- Tayar, Aline P'nina (2000). "A View from the Balcony". How Shall We Sing?: A Mediterranean Journey Through a Jewish Family. Sydney: Picador. ISBN 9780330362115. OCLC 50696540.

- Wilson, Neil (2000). Malta. Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781864501193. OCLC 1028322778.

Documents

[edit]Minutes

- Grech, Josef (20 July 2017a). "Minuti - Laqgha tal-Kunsill Lokali Marsaskala" (PDF) (in Maltese). Marsaskala Local Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2018.

- Grech, Josef (23 June 2017b). "Minuti - Laqgħa b'urġenza tal-Kunsill Lokali Marsaskala" (PDF) (in Maltese). Local Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2018.

- Grech, Josef (27 July 2017c). "Minuti - Laqgħa b'urġenza tal-Kunsill Lokali Marsaskala" (PDF) (in Maltese). Local Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2018.

- Grech, Josef (16 June 2017d). "Agenda - Laqgha tal-Kunsill Lokali Marsaskala" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2018.

- Grech, Josef (17 May 2017e). "Agenda - Laqgha tal-Kunsill Lokali Marsaskala" (PDF). p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2018.

- Grech, Josef (25 May 2017f). "Minuti - Laqgha tal-Kunsill Lokali Marsaskala". Archived from the original on 6 January 2018.

Reports

- Board Minutes (21 June 2017). Case Number: PA/02240/17 - Report Name (Report). Planning Authority. p. 1. Archived from the original on 12 March 2019.

- Livori, Roderick (2017). "PA Case Details (PA/02240/17): This application has been approved by the EPC/MEPA Board". Planning Authority (PA). Archived from the original on 12 March 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- Mapping Unit (July 2006a). "Southern Malta Local Plan: Marsascala Building Heights". MEPA. Archived from the original on 11 January 2018.

- Mapping Unit (July 2006b). "Southern Malta Local Plan: Marsascala - North Policy Map". MEPA. Archived from the original on 11 January 2018.

- Marsaskala Local Council (2010). "Rapport Amministrattiv" (PDF) (in Maltese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2018.

- MEPA (2005). South Malta Local Plan - Public Consultation Comments (within scheme) (Report). pp. 43, 44.

- National Gov. Pub. (1975). Report on the working of government departments. Valletta: Department of Information. OCLC 2906135.

- PA (2017). "Multiple Imaging: PA/02240/17". Planning Authority (PA). Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- PA; MTA (2018). "Breaktime from Excavation and Demolition Works" (PDF). Planning Authority and Malta Tourism Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2018.

- Studio Malta (Spring 2008). "Marsaskala Action Plan: A Transit Village for a Sustainable Community" (PDF). Projects Development and Co-ordination Unit (PDCU): Ministry for Urban Development & Roads (MUDR). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2018.

- Sultana, David (3 August 2017). "Re: Appeal from refusal for PA 3726/16". Floriana: Environment and Planning Review Tribunal (EPRT). Archived from the original on 1 July 2018.

Journals

[edit]Academic

- Cilia, George (2002). "Il-Kebbies tal-Fanali f'Wied il-Ghajn" (PDF). L-Imnara (in Maltese). 7 (1). Ghaqda Maltija tal-Folklor. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2019.

- Young, Bruce (March 1983). "Touristization of traditional Maltese fishing-farming villages: A general model". Tourism Management. 4 (1). Elsevier Ltd: 35–41. doi:10.1016/0261-5177(83)90048-1.

Gazettes

- Planning Authority (5 April 2017). "Planning Authority Notices" (PDF). The Malta Government Gazette (19, 754). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2018.

- Planning Authority (5 April 2017a). "Full Process - Full Development Applications" (PDF). The Malta Government Gazette (19, 754). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2018.

- Planning Authority (26 July 2017b). "Full Process - Full Development Applications" (PDF). The Malta Government Gazette (19, 838). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2018.

Magazines

- Attard, Anton (July 2017a). "Il-Kult ta' Sant'Anna" (PDF). Flimkien: Ħolqa Bejnietna - Parroċċa Sant'Anna (in Maltese) (300). Marsaskala: Parish Pastoral Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2018.

- Cassar, Maria Grazia (January 2018). "Asking Politicians to Listen" (PDF). Vigilo (49). Din l-Art Ħelwa. ISSN 1026-132X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- Time & Tide (1971). "Malta". Time & Tide. 52. Time and Tide Publishing Company. ISSN 0040-7828. OCLC 11561154.

News

[edit]- MEPA (10 November 2016). "Marsascala Sodium Lamps to Metal Halide lamps UIF". Malta Environment and Planning Authority (MEPA) - News Details. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019.

Newspapers

- Attard, Alex (22 June 2017b). "Permess ghal bini ta' erba' villel f'zona ODZ fil-Kalkara u f'Marsaskala: L-Awtorita tal-ippjanar tapprova biex l-eqdem binja f'Marsaskala tinbindel fi propjeta' kummercjali, restorant u parti minnha tkun residenzjali". In-Nazzjon (in Maltese). No. 14, 707. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017.

- Carabott, Sarah (24 June 2017c). "Council appeals demolition of one of town's oldest buildings". Times of Malta.

- Cassar, Maria Grazia (12 July 2017a). "Demolition of irreplaceable buildings - protecting the vernacular". The Malta Independent. No. 6, 135. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018.

- Cassar, Maria Grazia (12 July 2017c). "Demolition of irreplaceable buildings - protecting the vernacular". The Malta Independent. No. 6, 135. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018.

- Debono, James (26 April 2017c). "Restaurant proposed instead of old building in Marsaskala". Malta Today. No. 519. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018.

- Debono, James (21 June 2017g). "Marsascala's Oldest building set for demolition". Malta Today. No. 543. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018.

- Independent (31 July 2017c). "TMID Editorial: Environment and heritage - The little old house in Marsascala". The Malta Independent. No. 6, 151. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018.

Online news

- Bonnici, Julian (30 July 2019). "Keith Schembri's Company Is Heading Design Of St Julian's Property Long Accused Of Breaching Planning Permits". Lovin Malta.

- Bonnici, Owen (10 December 2005). "Farm fishing in Marsascala". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018.

- Borg, Amy (21 June 2017a). "marsaskala leqdem bini" (in Maltese). Net News. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018.

- Borg, Amy (21 June 2017b). "marsaskala leqdem bini 2" (in Maltese). Net News. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018.

- Cacopardo, Carmel (21 May 2010). "The concrete jungle at Marsascala". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018.

- Carabott, Sarah (18 May 2017a). "19th century Marsascala building has no outstanding features, says Cultural Heritage Superintendent: It formed part of a row overlooking the bay". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018.

- Carabott, Sarah (10 May 2017b). "Old Marsascala building may be wrecked for restaurant". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018.

- Cassar, Joanne (25 October 2017). "Stivala Group secured bonds fully allocated". The Malta Independent. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020.[1]

- Consiglio, John (4 August 2018). "Building uglification". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018.

- Debono, James (25 September 2014). "MEPA board unanimously rejects Sliema beach concessions: MEPA rejects applications for beach concessions on Ghar id-Dud and Qui-Si-Sana coastline". Malta Today. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018.

- Debono, James (30 November 2016). "Tower rises instead of rubble in Gozo: A modern version of a knight's tower has been built in place of a pile of rubble in Zebbug, Gozo, after the Planning Authority approved the 'reconstruction' of a two-storey building". Malta Today. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018.

- Debono, James (28 April 2017a). "Restaurant proposed instead of old building in Marsaskala". Malta Today. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018.

- Debono, James (21 June 2017b). "Marsascala's oldest building set for demolition: The Planning Authority has approved the demolition of Marsascala's oldest building to make way for a restaurant and a new dwelling". Malta Today. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018.

- Fenech, Gerald (7 July 2017). "Partit Demokratiku questions how it is that the Superintendent of Cultural Heritage has remained silent". Malta Winds. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017.

- Grech, Helena (29 July 2017g). "Change of heart: Marsascala local council not appealing demolition of 100-year-old building". The Malta Independent. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018.

- Independent (5 September 2008). "Pedestrianisation Pilot project in Marsascala this weekend". The Malta Independent. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018.

- Independent (2 June 2013). "The Marsascala of my childhood". The Malta Independent. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018.

- Independent (21 August 2016). "Jerma Palace, set to be demolished, makes it to Telegraph's list of 14 'fascinating' hotels". The Malta Independent. Archived from the original on 9 January 2018.

- Independent (24 June 2017a). "Marsascala local council decides to appeal demolition of old building". The Malta Independent. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018.

- Independent (6 July 2017b). "Why has Superintendent of Cultural Heritage remained silent, PD asks". The Malta Independent. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017.

- Malta Today (23 June 2017). "Council to appeal PA's decision greenlighting demolition of Marsascala's oldest building: The 'historic landmark' is earmarked for a restaurant and a new dwelling". Malta Today. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018.

- Mamo, Matthew (23 June 2017). "Il-Kunsill Lokali ta' Marsaskala se jappella kontra l-qerda ta' binja antika". Net News (in Maltese). Archived from the original on 28 July 2018 – via MaltaNews Today.

- Martin, Ivan (12 November 2015). "Architect furious over building permit issued without his knowledge on land he owns". Times of Malta.

- Martin, Ivan (5 May 2017). "Exponential growth in heritage watchdog's workload: From 40 cases in 2013 to 5,000 last year". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018.

- Mintoff, Christopher (24 June 2019). "Want to be a contractor? Just get some equipment: Industry built on amateurs, and a new illogical rule - former chamber president". Times of Malta.

- Mifsud, Nigel (4 July 2017). "Construction sites allowed to continue excavation and demolition to avoid danger". TVM. Archived from the original on 26 August 2018.

- Net (21 June 2017). "F'Marsaskala approvat permess biex titwaqqa' l-eqdem binja". Net News (in Maltese). Archived from the original on 14 July 2018.

- One (23 June 2017). "Il-Kunsill Lokali ta' Marsaskala kontra t-twaqqiegħ ta' binja antika". One News (in Maltese). Archived from the original on 15 January 2018.

- Times (23 June 2017). "Marsascala council refuses to accept PA decision: Appeal tries to save oldest building in the village". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017.

- Times (7 March 2018). "New Superintendent of Cultural Heritage before the end of the month: Project aimed to place more sites in Malta on Unesco list launched". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018.

- Torpiano, Alex; Zammit, Giovanni (9 November 2019). "Gozo: a wave of destruction". Times of Malta.

- TVM (22 June 2017). "Ħarsa lejn l-istejjer ewlenin fil-ġurnali". TVM (in Maltese). Archived from the original on 28 August 2018.

- Urpani, David Grech (2017). "Marsascala Local Council Opposes Demolition Of Town's Oldest Building: They're not having any of it". Lovin Malta. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018.

- Vassallo, Raphael (29 June 2015). "Poised for an architectural revolution: Chris Mintoff, chairman of the KTP [Chamber of Architects], welcomes high-rise development as a challenge to architects, but warns against a short-termist approach". Malta Today.

Other

[edit]Websites

- Cassar, Maria Grazia (8 October 2017b). "Protecting the Vernacular: The Demolition of Irreplaceable Buildings". Din l-Art Ħelwa (National Trust of Malta). Archived from the original on 23 July 2018.

- Dietrich, Jörg (June 2010). "Triq Ix-Xat (Marina Street)". Panaorama Street Line. Marsascala, Malta. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018.

- Marsaskala Local Council (2012). "The Regenarationof the Tourism Market in Marsaskala". European Regional Development Fund (ERDF): Application Description. Archived from the original on 25 November 2013.

- Marsaskala Local Council (2014). "Marsaskala". Active Aging. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018.

- MDA (2018). "Tourism Areas exempt from demolition and excavation works in summer". Malta Developers Association. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018.

- My Guide Malta (2018). "Marsaskala in Malta". My Guide Network. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018.

- Net News (23 June 2017). "Il-Kunsill Lokali ta' Marsaskala qabel b'mod unanimu li jappella kontra d-deċiżjoni tal-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar biex titwaqqa' waħda mill-eqdem binjiet fil-lokalità". Facebook. Archived from the original on 26 August 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- Restoration Directorate (2012). "St. Anne's Chapel, Marsascala". Government of Malta. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018.

- Scerri, John. "Wied il-Ghajn (Marsascala)". malta-canada.com (in Maltese). Archived from the original on 29 July 2018.

- Stivala, Carmelo (2018). "Stivala Group Finance p.l.c." Gżira: Stivala Group of Companies. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018.

- Vella, Fiona (11 August 2014). "Il-ġrajja ta' Grabiel". Leħen Ir-Ramla (in Maltese) (16). Għaqda Bajja San Tumas. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018.

- Zen, Suki (18 April 2009a). "The Three Crosses". Anecdotes from Malta. Archived from the original on 5 August 2018.

- Zen, Suki (29 May 2009b). "Old Abandoned Buildings in Marsascala". Anecdotes from Malta. Archived from the original on 9 January 2018.

Dissertations

- Vella, Alexia (2017). A study of residents' opinion on land-use change in Marsaskala (B. Sc.). University of Malta. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to 3, Triq ix-Xatt at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 3, Triq ix-Xatt at Wikimedia Commons