2023 Hawaii wildfires

| 2023 Hawaii wildfires | |

|---|---|

Top: Lāhainā burning as seen from the ocean and harbor Middle: Burned cars and buildings Bottom: FEMA officials perform searches and Governor Josh Green reviews damage | |

| Date(s) | August 8–16, 2023 |

| Location | Hawaii, United States |

| Statistics | |

| Total fires | 4 |

| Total area | 17,000+ acres (6,880+ ha)[1] |

| Impacts | |

| Deaths | 102+[2] |

| Non-fatal injuries | 67+[3] |

| Missing people | 2[4] |

| Structures destroyed | 2,207[5] |

| Damage | $5.5 billion[6] |

| Ignition | |

| Cause | |

| Map | |

Centroids of fires detected by spaceborne infrared imaging on August 8–10. Some parts are perimeters. (map data) | |

In early August 2023, a series of wildfires broke out in the U.S. state of Hawaii, predominantly on the island of Maui. The wind-driven fires prompted evacuations and caused widespread damage, killing at least 102 people and leaving two people missing in the town of Lahaina on Maui's northwest coast. The proliferation of the wildfires was attributed to dry, gusty conditions created by a strong high-pressure area north of Hawaii and Hurricane Dora to the south.[11]

An emergency declaration was signed on August 8, authorizing several actions, including activation of the Hawaii National Guard, appropriate actions by the director of the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency and the Administrator of Emergency Management, and the expenditure of state general revenue funds for relief of conditions created by the fires.[12] By August 9, the state government of Hawaii issued a state of emergency for the entirety of the state.[11] On August 10, U.S. President Joe Biden issued a federal major disaster declaration.[13]

For the Lahaina fire alone, the Pacific Disaster Center (PDC) and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) estimated that over 2,200 buildings had been destroyed,[5][14][15] overwhelmingly residential[16][17] and including many historic landmarks in Lahaina.[18][19] The damage caused by the fire has been estimated at nearly $6 billion.[5][20] In September 2023, the United States Department of Commerce published the official damage total of the wildfires as $5.5 billion (2023 USD).[6]

Background

[edit]Wildfire risk

[edit]

The typical area burned by wildfires in Hawaii has increased in recent decades, almost quadrupling. Experts have blamed the increase on the spread of nonnative vegetation and hotter, drier weather due to climate change.[22]

During the 2010s and early 2020s, Clay Trauernicht, a botanist and fire scientist at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, and several other experts warned that the decline of agriculture in Hawaii meant that large areas of formerly productive land had been left unmanaged; nonnative invasive species like guinea grass were spreading rapidly and increasing the risk of large wildfires.[23][24][25][26][27] The state government failed to provide incentives or impose mandates to keep land clear of grass.[26][27] The state government also did not require all structure owners to maintain defensible space, a standard rule in fire-prone states like California.[27][28] The shrinking of the agricultural workforce reduced overall firefighting capacity; those workers had traditionally suppressed fires on the land they cared for, and were so effective that sometimes the counties called them for help.[23] In 2022, Trauernicht suggested that Hawaii follow Europe's example by subsidizing agriculture as a public good as a form of fire risk reduction.[24] In 2023, UH Manoa biogeography professor Camilo Mora estimated the cost of land restoration to mitigate wildfire risk at about $1 billion.[26] Despite these calls to action, the Hawaii State Legislature had been unable to make much progress; a 2022 bill to spend just $1.5 million on additional fire risk reduction measures died in a legislative committee.[26]

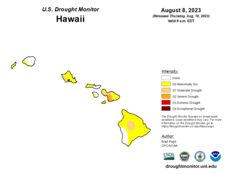

Around the time the fires occurred, twenty percent of the county of Maui was experiencing moderate drought (level 1 of 4), and sixteen percent of the county was under severe drought conditions (level 2 of 4).[29] A decrease in rainfall consistent with the predicted impacts of climate change had also been recorded in the Hawaiian Islands, according to the U.S. National Climate Assessment.[30] In the decades leading up to the fire, overdevelopment practices led to further water management challenges that reduced the availability of water for firefighting and exacerbated drought conditions.[31]

In June 2014, the Hawaii Wildfire Management Organization, a nonprofit organization, prepared a Western Maui Community Wildfire Protection Plan which warned that most of the Lahaina area was at extremely high risk for burning.[32][33]

In Maui County's 2020 Hazard Mitigation Plan, the county identified Lahaina, the most heavily impacted community in the August fires, as lying within a high risk zone for wildfire.[34]: 481–522

In its monthly seasonal outlook on August 1, 2023, the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) forecast "above normal" potential for significant wildland fires for Hawaii in August, concentrated on the islands' leeward sides. In addition to noting plentiful vegetation growth from the previous wet season and the expanding drought, the NIFC mentioned that "tropical cyclones can also bring windy and dry conditions depending on how they approach the island chain and can exacerbate fire growth potential".[35]: 1, 2, 7

The vulnerability of the islands to deadly wildfires was gravely underestimated in long term assessments. A year prior, the State of Hawaii Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan Report had detailed wildfire risks as one of the lowest threats for the state.[36] A 2021 Maui County assessment acknowledged the spike of wildfires in the state, but described funds as "inadequate" and heavily criticized the county fire department's strategic plan, claiming it said "nothing about what can and should be done to prevent fires."[37]

Weather factors

[edit]

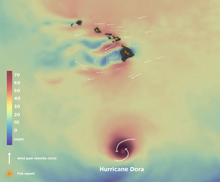

In early August 2023, a high-pressure system remained north of the Hawaiian Islands. This formed strong surface pressure north of the islands, and also sustained stabilization across the region, creating warm and sunny conditions. Concurrently, Hurricane Dora began to intensify to Category 4 strength, which helped to create a large pressure difference between the high-pressure area and the low-pressure cyclone.[38] This pressure difference aided in already significant trade winds moving southwest, and formed strong gradient winds over the islands.[38][39] (A similar phenomenon occurred during the October 2017 Portugal wildfires during the passage of Hurricane Ophelia.)[40] The exact significance of Hurricane Dora and how it impacted the fires themselves remains somewhat unclear. Meteorologists noted that the storm's center remained more than 700 miles (1,100 km) from the islands and that it remained relatively small in size; however it also remained "remarkably potent for a long time", logging more hours as a Category 4 hurricane than any other storm in the Pacific for over 50 years.[41] Philippe Papin, a hurricane specialist with the National Hurricane Center, argued that Hurricane Dora played only a minor role in "enhancing low-level flow over Maui at fire initiation time."[42]

By August 6, the National Weather Service identified a region of very dry air arriving from the East Pacific, greatly inhibiting the potential for rainfall.[43] A prominent descending capping inversion forced even more stabilization of the atmosphere, which led to enhanced wind gusts and very dry conditions between August 7 and 8.[43] As the day progressed, deep layer ridging combined with the existing pressure gradient created very strong wind gusts and caused humidity levels to be well below normal. The aforementioned cap was expected to only strengthen acceleration of wind due to terrain features near the islands.[44]

List of wildfires

[edit]

| Name | County | Acres | Start date | End date | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olinda | Maui | 1,081 | August 8 | September 28[a] | [45][46] |

| Kula | Maui | 202 | August 8 | September 28[a] | [45][47] |

| Lahaina | Maui | 2,170 | August 8 | September 3 | [48][49] |

| Pulehu | Maui | 3,268 | August 8 | August 12 | [50][51] |

Timeline

[edit]

During the first few days of August, a multitude of minor brush fires affected the Hawaiian Islands. Multiple brush fires burned on the island of Oʻahu, stretching fire department resources, but were quickly contained by August 4. The island's south and west sides remained abnormally dry or in drought because of the fire, as well as weather conditions.[52][53]

At 5:00 a.m. HST (UTC 15:00) on August 7, the National Weather Service's office in Honolulu issued a red flag warning for the leeward portions of all the islands until the morning of August 9, highlighting that "very dry fuels combined with strong and gusty easterly winds and low humidities will produce critical fire weather conditions through Tuesday night". East winds of 30–45 miles per hour (48–72 km/h) with gusts over 60 miles per hour (97 km/h) were forecast.[54] In Maui County, officials reported gusts up to 80 miles per hour (130 km/h) in the Upcountry Maui area.[55]

Maui

[edit]

On August 4, 2023, at 11:01 a.m. HST (UTC 21:01), the first of many small fires ignited on Maui. A 30-acre brush fire was reported adjacent to the Kahului Airport in a field. By 9:29 p.m. HST (UTC 07:29), the fire was reported 90% contained,[56][57][58] but many flights out of the airport were delayed to August 11.[59]

On August 8, 2023, intense winds knocked down numerous utility poles. By 4:55 p.m. HST (UTC 02:55), "about 30 downed poles" had been reported on Maui, resulting in "at least 15 separate outages impacting more than 12,400 customers". By that time, there had been no power in some parts of West Maui since 4:50 a.m. HST (UTC 14:50).[60]

Kula

[edit]The first significant fire of the event was reported at 12:22 a.m. HST (UTC 10:30) on August 8 near Olinda Road in the community of Kula, in Upcountry Maui.[61] Evacuations of nearby residents were announced beginning at 3:43 a.m. (UTC 13:43).[62][63] As of August 9, the fire had burned approximately 1,000 acres (400 ha).[55] Approximately 544 structures were exposed, 96% of which were residential,[64] and 16 burned.[65] Concurrent electrical grid sensor data and security camera footage reported by The Washington Post indicate that a downed power line, hit by a tree, may have caused this fire.[8]

Lahaina

[edit]

The most significant fire of the complex of events began from a brush fire ignited in West Maui near the town of Lahaina on the morning of August 8.[66][67][68][69] During the early morning hours of August 8, significant straight-line winds began to impact the town of Lahaina.[70] Peak wind gusts that exceeded 80 miles per hour (130 km/h) began to cause minor damage to homes and buildings in Lahaina, and subsequently, a power pole was snapped along Lahainaluna Road, across the street from the Lahaina Intermediate School near the northeast side of town.[70]

A three-acre (1.2 ha) brush fire was reported at 6:37 a.m. HST (UTC 16:37) as the downed power line sparked flames to dry grass near the road.[32][71][61] Evacuations were ordered minutes later in the areas around Lahaina Intermediate School. Maui County Fire Department immediately responded, and by 9:00 a.m HST (UTC 19:00), the fire was announced fully contained.[72]

As wind gusts continued to batter the town, the fire was thought to have been extinguished.[9] By 3:30 p.m. HST (UTC 01:30), the fire had flared up again, and forced the closure of Lahaina Bypass (Route 3000), with more evacuations nearby following.[32][73] Residents on the west side of town received instructions to shelter in place.[71]

The wildfire rapidly grew in both size and intensity.[70] Wind gusts pushed the flames through the northeastern region of the community, where dense neighborhoods were.[74][75] Hundreds of homes burned in a matter of minutes, and residents identifying the danger attempted to flee in vehicles while surrounded by flames.[76] As time progressed, the fire moved southwest and downslope towards the Pacific coast and Kahoma neighborhood.[73] Firefighters were repeatedly stymied in their attempts to defend structures by failing water pressure in fire hydrants; as the melting pipes in burning homes leaked, the network lost pressure despite the presence of working backup generators.[77]

At 4:46 p.m. HST (UTC 02:46), the fire reportedly crossed Honoapiʻilani Highway (Hawaii Route 30) and entered the main part of Lahaina,[32] forcing residents to self-evacuate with little or no notice.[73] At this time, bumper-to-bumper traffic developed.[70] By 5:45 p.m. HST (UTC 03:45), the fire had reached the shoreline, when the United States Coast Guard first learned of people jumping into the ocean at Lahaina to escape the fire.[32] Survivors later recalled getting trapped in a traffic jam and realizing they needed to go into the water when cars around them either caught fire or exploded.[78][79]

Officials said that civil defense sirens were not activated during the fire[71] even though Hawaii has the world's largest integrated outdoor siren warning system, with over 80 sirens on Maui alone meant to be used in cases of natural disasters.[80] Several residents later told journalists that they had received no warning and did not know what was happening until they encountered smoke or flames.[71][81] There had been no power or communications in Lahaina for much of the day,[73] and authorities issued a confusing series of social media alerts which reached a small audience.[82]

The death toll stood at 67 on August 11, but that number reflected only victims found outside buildings, because local authorities had waited for FEMA to send its specialized personnel to search building interiors. According to federal officials, many of the victims found outside "were believed to have died in their vehicles".[83] The fire burned 2,170 acres (880 ha) of land.[16][14] PDC and FEMA estimated that 2,207 buildings had been destroyed, with a total of 2,719 exposed to the fires,[5] and set the damage estimate at $5.52 billion as of August 11. The next day, Governor Josh Green announced the damage was close to $6 billion.[20][84] Many historic structures were destroyed, including Waiola Church and Pioneer Inn.[85] 86% of burned structures in Lāhaina were residential.[16][64]

As of August 12[update], at least 93 people had been confirmed dead in and around Lahaina[86] with only 3% of the area searched.[87][88] The number of dead was expected to rise further as FEMA search-and-rescue specialists searched the interiors of burned-down buildings. Very few victims had been identified.[17][89]

By August 24[update], with 100% of the single-story, residential properties searched of the disaster area, 115 casualties had been confirmed with an additional 388 people missing.[90][91] On September 7[update] officials reported that 99% of the area had been searched, with the death toll unchanged at 115 and the missing count reduced to 110.[92] The disaster area remained restricted to authorized personnel due to unstable structures, exposed electrical wires, and potentially toxic ash and debris. The following day, the missing count was further reduced to 66 people.[93] On September 15, the death toll was reduced from 115 to 97 as officials reported that DNA findings discovered that some of the remains came from the same victims. The number of missing persons was also reduced to 31 with only 1 addition to the list.[94]

On September 25 a small number of residents were allowed to enter North Lahaina for the first time in over 6 weeks.[95] Officials planned to remove restrictions for all areas of the city over the next one to two months, pending cleanup efforts by the EPA.[96]

The Lahaina fire's death toll was the largest for a wildfire in the U.S. since the Cloquet fire of 1918, which killed 453 people.[97][15][98]

Pūlehu-Kīhei

[edit]

On the same night as the Kula and Lahaina fires, another major fire sparked near Pūlehu Road, north of Kīhei. The fire quickly spread in the direction of the prevailing winds, and by early August 9, the large fire entered northeast portions of Kīhei, resulting in an evacuation order for multiple communities nearby. Within the following days, firefighters fully contained the fire and all residents were advised that it was safe to return.[99]

Other fires

[edit]A small, single acre fire ignited on August 11, which led to the evacuation of Kāʻanapali in West Maui before it was contained that same day.[100][101] Another fire in Kāʻanapali would ignite again on August 26 and have an evacuation order placed and lifted on the same day.[102]

Hawaiʻi Island

[edit]In Hawaiʻi County, neighborhoods in the North and South Kohala districts of the Island of Hawaiʻi were evacuated due to rapidly spreading brush fires.[103] On August 9, several other brush fires broke out near the communities of Nā'ālehu and Pāhala; those fires were quickly brought under control.[103] Hawaiʻi County Mayor Mitch Roth said there were no reports of injuries or destroyed homes on the Big Island.[104]

Oʻahu

[edit]On August 16, a large brushfire sprung up on the outskirts of Wahiawā on Oʻahu. Though it did not burn near any houses, the fire threatened local unhoused people as well as the Kūkaniloko Birth Site, a location registered under the National Register of Historic Places and near-thousand year old site that is the location of the births of Hawaiian chiefs.[105]

Impact

[edit]

The governor of the state of Hawaii, Josh Green, referred to the Lahaina wildfires as the "worst natural disaster" in the history of Hawaii.[b][108] It is the fifth deadliest wildfire in United States history, and the most lethal wildfire in the country since the Cloquet fire of 1918, which killed 453 people.[109][110]

Casualties

[edit]| Date | Fatality | Missing | % searched |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13-Aug | 96 | ||

| 14-Aug | 99 | 25% | |

| 15-Aug | 106 | ||

| 16-Aug | 111 | ||

| 19-Aug | 114 | 85% | |

| 21-Aug | 115 | ||

| 22-Aug | 115 | 1,000-1,100[112] | |

| 24-Aug | 115 | 388[113] | |

| 29-Aug | 115 | 100% | |

| 18-Sep | 97[114] | ||

| 29-Sep | 98 | 12[115] | |

| 14-Nov | 100 | 4[116] | |

| 13-Feb 2024 | 101 | 2[4] | |

| 24-Jun 2024 | 102 | 2[2] |

As of June 24, 2024[update], there were 102 confirmed deaths due to the Lahaina fire on Maui,[2] all of whom have been identified.[117][118] An additional two individuals remain unaccounted for as of February 14, 2024.[4] Among the dead was confirmed to be a Filipino national who was a naturalized U.S. citizen.[119] The death toll in West Maui made it the deadliest wildfire and natural disaster ever recorded in Hawaii since statehood.[22][120]

As of August 18[update], at least 67 people were injured in the fires.[3] On August 9, at least twenty individuals were reported hospitalized at a Maui hospital. Six additional individuals, three of whom had critical burns, were reportedly transported by air ambulance from Maui to hospitals on Oʻahu.[121]

On August 17, 60 survivors were found alive sheltering inside a single home.[122]

At times after the fire, the reported number of casualties was thought to be as high as 115. Using DNA testing, it was eventually established that the total number of casualties was 102. [123]

Damage

[edit]

The main Maui wildfire burned much of the community of Lahaina, where more than 2,200 structures were damaged or destroyed, including much of the downtown Lahaina Historic District centered on Front Street.[5][68][67] 96% of burned structures were residential.[17] The 3.4-square-mile area (8.8 km2) was the commercial, residential, and cultural center of the community.[124] On August 17, Governor Green noted that the fire temperature had reached 1,000 °F (538 °C), since it was hot enough to melt granite counters and engine blocks.[125] Puddles of melted aluminum have been seen underneath burned-out vehicles.[125]

Although PDC and FEMA had initially estimated total damage at around $5.52 billion,[5] catastrophe modeling firm Karen Clark & Co. estimated on August 16 that insured property losses would be only $3.2 billion.[126] Real estate experts expressed concern that many Lahaina homes were uninsured or underinsured and surviving owners might not have sufficient financial resources to build new homes in compliance with the state's current building code.[127] Many Native Hawaiians were able to afford to live in Lahaina only because they had inherited paid-off homes from previous generations, and since they had not needed mortgage loans to purchase their homes, they were not required to carry homeowners insurance coverage.[127]

The Lahaina Historic District, which was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1962 and was the capital of the Kingdom of Hawaii for 35 years, suffered extensive fire damage.[128] Among the structures destroyed were:

- The Waiola Church, which celebrated its 200th anniversary in May 2023, lost its main sanctuary, annex, and social hall.[128][129] Waiola Church's cemetery is the burial ground for members of the Hawaiian Royal Family, including Queen Keōpūolani, who founded the church in 1823.[129]

- The Lahaina Jodo Mission, a Buddhist temple in northern Lahaina. Established in 1912 and stood on its current location since 1932.[128]

- The Pioneer Inn, a landmark town hotel constructed by George Alan Freeland in 1901.[128]

- The Nā ʻAikāne Cultural Center, a local cultural center which once housed a soup kitchen for striking plantation workers during an International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) strike against the Pioneer Mill.[128]

- The Old Lahaina Courthouse, which first operated in 1860 as a customs house for trade and whaling ships. The building's roof was completely destroyed.[130] The Old Lahaina Courthouse stands in heavily damaged Lahaina Banyan Court Park.

- The Lahaina Heritage Museum and its collection, which were housed inside the Old Courthouse building, were also destroyed. The collection included items that spanned Lahaina's history, including artifacts from the area's ancient Hawaiian period, the Hawaiian Kingdom and monarchy, the plantation period, and the town's whaling era. Copies of the museum's documents had been digitized and stored online prior to the fire.[130]

- The Baldwin Home Museum, which was constructed in 1834 and 1835 as the home of American missionaries Dwight Baldwin and Charlotte Fowler Baldwin, burned to the ground.[130] The Baldwin Home was the oldest house on the island of Maui.[128][130] Historic items lost in the house fire included Baldwin's medical instruments he used to vaccinate much of Maui's population against smallpox in the 1800s, seashell collections, and the family's furniture and rocking chairs from the East Coast.[128][130]

- The Wo Hing Society Hall, built in the early 1910s to serve the growing Chinese population in Lahaina. It was restored and turned into the Wo Hing Museum in the 1980s.[131]

The fire also destroyed several cell towers in affected areas, causing service outages and 9-1-1 emergency telephone services to be rendered unavailable.[132] The wildfire that burned near the community of Kula, located in Maui's Upcountry, destroyed at least two homes.[99]

The Maria Lanakila Catholic Church in Lahaina, which had been dedicated in 1858. Contrary to early reports, the main church building and steeple were not destroyed and survived the fire largely intact, though the roof and interior may have sustained some damage.[128][129]

The Lahaina Civic Center, venue for the Maui Invitational Tournament, a prominent early-season college men's basketball event, has so far escaped significant damage, although it had to be evacuated after earlier serving as an evacuation center. The 2023 tournament, scheduled for November, was moved to Honolulu at the Stan Sheriff Center instead.[133]

Environment

[edit]

Lahaina's famous banyan tree, the largest banyan tree in the United States, had most of its foliage charred, though was left standing after the fire.[134] A video taken on August 11 showed local officials watering the tree to aid its recovery. At least some green foliage appeared to be present and the roots, trunks, and branches of the tree were largely undamaged.[135]

On August 11, unsafe water alerts were issued as early as 3 p.m. (01:00 UTC) warning residents of Lahaina and Upper Kula, with instructions to not drink or use tap water for daily activities, even after boiling, and all residents were requested to limit water use.[136][137][138][139] Following earlier deployments on August 9, further potable water tankers were set up at locations across the island.[140] Some scientists have also warned that charred soils, toxic contaminated top soil and other debris could run off into the shoreline and cause marine habitats and coral to be damaged.[141]

Evacuations

[edit]The fires prompted mass evacuations of thousands of residents and visitors from Lāhaina, Kāʻanapali, Kīhei, and Kula.[142] The U.S. Coast Guard confirmed that they had rescued 17 people who had jumped into the sea in Lahaina to escape the fires.[143] As of August 12, more than 1,400 people on Maui remained in shelters.[144][145] Vacationing San Francisco mayor London Breed was among those evacuated from Maui.[146]

An estimated 11,000 people flew out of Maui via Kahului Airport on August 9, 2023.[104]

American, Southwest, Hawaiian, and Alaska Airlines had added additional flights to their routes into Kahului Airport by August 10 to help evacuate people from the island, and American replaced a narrow-body Airbus A321 with a wide-body Boeing 777 to further boost capacity.[147] All four airlines had also reportedly waived fare cancellation penalties and fare-difference fees for affected passengers,[147] and Hawaiian and Southwest offered temporary $19 interisland flights until August 11.[148][149] By August 13, 2023, over 46,000 visitors had flown out of Maui via Kahului Airport.[150]

Hawaiian state officials created plans to house visitors along with thousands of displaced Maui residents at the Hawaii Convention Center in Honolulu, Oʻahu[104] and over 100 had stayed as of August 10.[151]

After the fire swept through Lahaina on August 8, Maui County blocked public access to all of West Maui with checkpoints on Route 30/340 (Honoapiʻilani Highway, the only highway in and out of the area). Over the next three days, the blockade created a desperate situation for residents of still-intact communities who ran low on medicine, food, and fuel, while other residents and tourists who suddenly found themselves outside of the blockade wished to retrieve their belongings. On August 11, 2023, the County reopened the checkpoint on Route 30 at Māʻalaea to help ameliorate these issues. Within five hours, the checkpoint was closed again, reportedly because of attempts to enter the sealed-off portion of Lahaina.[152][153]

On September 25 officials cleared a small area in North Lahaina for reentry, the first time in over 6 weeks that residents had been allowed back into the city.[95] Visiting residents were provided with personal protective equipment and urged not to disturb the ash, which may contain hazardous materials such as asbestos and lead.[95]

Wildlife and pets

[edit]The Maui Humane Society stated that there is an estimated 3,000 animals from Lahaina that were currently missing after the fires as of August 16. As of August 14, the society had received about 367 lost animal reports and some dual reported with the society and on the "Missing Pets of Maui" Facebook page created by the society which has about 6,400 members.[154] Any found animals are checked for any identification and scanned for a microchip, with the society urging that found deceased animals should not be moved or destroyed so that they can be cataloged and checked for any identification.[155]

Animal welfare advocates and the Maui Police were working in tandem to search the burned areas for lost, injured or deceased animals, with dozens of feeding and drinking stations set up to draw out animals.[156] After the fire in order to make room for animals that were impacted by the fires, the Humane Society, and the only open-admission animal shelter on the island airlifted over 100 shelter animals to Portland, Oregon.[157] Veterinarians and staff members of the Kīhei Veterinary Clinic, the Humane Society, and the Central Maui Animal Clinic and volunteers coordinated care for the found animals as well as disbursing free medical care, food and animal medication to island residents. Donations and care were also extended to the Maui Police Department's K-9 unit that are working with recovery efforts and housing for the animals.[154]

Scientists with the National Science Foundation and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began to prep for studies that would monitor and document any changes in water quality due to soil erosion and other effects of the fire that can affect the island's waterways and ecosystems. Others expressed thanks that areas such as the Maui Bird Conservation Center was spared from the majority of the fires, as it housed a large portion of the alalā flock.[158][159]

Legal proceedings

[edit]Within two weeks of the Maui wildfires, lawyers from California, Florida, Oregon, Texas, and Washington had come to Maui to sign up wildfire victims as plaintiffs.[160] Chief Disciplinary Counsel Bradley Tamm (the state's primary lawyer regulator) warned Hawaiians to be careful: "It’s a feeding frenzy. There are sharks both in the water and on the land".[160] Hawaiian Electric Industries Inc., the primary electric utility for Maui, became a significant focus of such litigation. By August 14, at least one lawsuit had been filed against Hawaiian Electric, and the company experienced a decline in its stock value.[161][162] A state circuit judge asserted he had the judicial right to end an impasse over who will have priority on payments – victims or the insurers. The order said although the insurance companies have a separate subrogation suit in Honolulu, the Maui court has the jurisdiction to resolve the issue to reach a “…just, efficient and economic determination of all the Maui Fire Cases.” The judge scheduled a “status conference” for August 2024 to determine the cause of the issues and resolve them.[163]

On August 9, 2023, a deputy attorney general representing the Board of Land and Natural Resources filed a petition for a writ of mandamus to the Hawai'i Supreme Court, alleging that a Hawaii circuit court judge's rulings regarding private water usage had restricted the amount of water available to fight the fires. This claim was disputed by the responding Sierra Club, who requested the Supreme Court to sanction the Attorney General for filing the petition under false pretenses. The attorney representing Maui County stated during the hearing that a lack of water was never an issue during the wildfires.[164] The Supreme Court denied the petition.[165]

On October 4, 2023, a filing with the Hawaii Public Utilities Commission showed that Hawaiian Electric was underinsured against its potential liability exposure for the Maui wildfires, with only about $165 million in liability insurance coverage.[166] According to ALM's Law.com, as of October 5, 2023, more than 35 lawsuits had been filed against Hawaiian Electric and other defendants.[167] Most but not all had been filed in Hawaii state circuit courts, especially the Second Circuit based in Wailuku (which has jurisdiction over Maui County).[167][168] In response, Hawaiian Electric retained California law firm Munger, Tolles & Olson as its lead defense counsel.[167] The same law firm had previously worked for Pacific Gas and Electric on litigation arising out of the 2018 California wildfires, in which its attorneys had billed their time in 2019 at rates between $400 and $1,400 per hour.[169]

On March 11, 2024, U.S. District Judge Jill Otake ordered the remand of 90 lawsuits back to state court.[170] The defendants had removed the cases to the federal district court in Honolulu on the basis of a 2002 law[171] which authorized federal jurisdiction over civil actions arising out of the deaths of at least 75 natural persons at a "discrete location".[170] Judge Otake held that the Lahaina fire was not a "discrete location" because the fatalities were spread out over seven square miles (18.1 km²).[170]

In July 2024, a tentative agreement was reached and Hawaiian Electric Industries, along with the State of Hawaii, Maui County, Kamehameha Schools and others would agree to pay thousands of plaintiffs and victims over $4 billion to settle the lawsuits.[172] A state circuit judge asserted he had the judicial right to end an impasse over who will have priority on payments – victims or the insurers. The order said although the insurance companies have a separate subrogation suit in Honolulu, the Maui court has the jurisdiction to resolve the issue to reach a “…just, efficient and economic determination of all the Maui Fire Cases.” The judge scheduled a “status conference” for August 2024 to determine the cause of the issues and resolve them.[163]

Response

[edit]Aug. 9: Hawaii Army National Guard Chinook drops water on the wildfire

Aug. 10: Hawaii Air National Guard offload supplies from a C-17 Globemaster III

Aug. 12: FEMA video footage of response and recovery

Aug. 21: President Biden visits Maui and speaks at Lahaina Civic Center

Federal government

[edit]U.S. President Joe Biden ordered the mobilization of "all available federal assets" to help respond to the wildfires. In a statement, Biden noted that the United States Navy Third Fleet and the United States Coast Guard were supporting "response and rescue efforts". The United States Department of Transportation was working with commercial airlines to help evacuate tourists from Maui.[173] To help with the ongoing Coast Guard search and rescue operation, the United States Navy sent in Helicopter Maritime Strike Squadron Three Seven (HSM-37) and two MH-60R Seahawk helicopters, with the United States Indo-Pacific Command standing ready to provide additional assistance as needed.[174][175] Meanwhile, the U.S. 25th Infantry Division from Schofield Barracks on Oʻahu was deployed alongside the Hawaii National Guard to Maui and Hawaii Island to assist with fire suppression support, search and rescue operations, and traffic control.[176]

President Biden approved the state of Hawaii's request for a major disaster declaration on August 10, making federal funding available for recovery efforts in the affected areas.[177] On August 10, FEMA initiated deployment of Urban Search and Rescue Task Force personnel from around the United States to Maui. Washington State Task Force 1 sent 45 specialists along with a 5-member K-9 team.[178][179] Each human member of the K-9 team works with a canine partner, a FEMA-certified human remains detection dog.[179] The same task force had previously deployed to Maui in 2018 to assist with the aftermath of Hurricane Lane.[179] On August 10, Nevada Task Force 1 was initially asked to send one K-9 handler and dog, who left that same day. The request was amended to four more specialists, then on top of that, a full 45-member task force team, all of whom flew out on August 11.[180]

FEMA initially provided $700 payments as one of several types of federal assistance available to survivors of the wildfire, which was meant to address immediate needs such as food, water, and clothing.[181]

California sent 11 members of Urban Search and Rescue task forces based in the cities of Sacramento, Riverside, and Oakland, and six employees of the California Governor's Office of Emergency Services.[182] On August 15, California announced that it was increasing its deployment to 101 people, including an incident management team of 67 Cal Fire employees.[183] Among the new personnel arriving on Maui were forensic anthropologists from Chico State who had helped identify victims of the Camp Fire (2018).[184]

By August 16, the number of FEMA cadaver dogs deployed to the scene had increased to 40,[185] and Governor Green explained that the searchers were in a "race against time" to recover remains before they could be degraded by the next rainstorm.[186] Each dog could only work for about 15 to 20 minutes in the tropical heat before rotating into an air-conditioned truck to cool down.[187] The dogs also had to wear booties to shield their paws from asphalt temperatures exceeding 150 °F (66 °C) and still-hot embers, but the booties themselves required frequent replacement.[187]

Meanwhile, on August 15, a federal Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Team (DMORT) arrived on the island to assist with the identification and processing of the large number of remains.[188] The DMORT brought along a portable morgue in the form of 22.5 short tons (20,400 kg) of equipment and supplies, and nine Matson shipping containers were seen outside the Maui Police Department's Forensic Facility in Wailuku.[189]

On August 17, a five-member National Response Team from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives arrived on Maui to investigate the cause and origin of the Lahaina fire.[190] The team included an electrical engineer from the Fire Research Laboratory.[190]

On August 21, President Biden and First Lady Jill Biden arrived at Kahului Airport, where they met with Governor Josh Green, his wife Jaime, as well as members of Hawaii's congressional delegation. The Bidens then boarded Marine One where they were given an aerial tour of the devastation. Biden then went to Lahaina where he met with first responders as well as local and state officials and FEMA administrator Deanne Criswell. The Bidens walked through the ruins of the town seeing the area firsthand. They also took part in a blessing by island elders. Biden then spoke to the community and met with survivors at the Lahaina Civic Center.[191]

By August 25, the FEMA Urban Search and Rescue task forces had searched 99% of the disaster area, and they wrapped up their work and returned home to the mainland United States.[192]

State government

[edit]Hawaii Lieutenant Governor Sylvia Luke, who was serving as acting governor in the absence of Governor Josh Green while he was traveling outside of Hawaii, issued an emergency proclamation and activated the Hawaii National Guard.[67] The Hawaii National Guard, together with the U.S. 25th Infantry Division from Schofield Barracks on Oʻahu, deployed to Maui and Hawaii Island to assist with fire suppression support, search and rescue operations, and traffic control. Two UH-60 Blackhawk and one CH-47 Chinook helicopters were also deployed to support fire suppression efforts.[176]

As of August 9, 2023[update], the Hawaii Tourism Authority was asking all visitors on Maui for non-essential travel to leave the island and strongly discouraged any further non-essential travel to the island.[104][193]

Previously closed to prioritize emergency services, access to West Maui via Honoapiʻilani Highway for residents with proof of residency and visitors with proof of hotel reservations was resumed beginning at 12 p.m. (UTC 22:00) on August 11.[194] However, at 4 p.m. (UTC 02:00) access was again restricted due to reports of people accessing restricted areas despite hazardous conditions.[195] Access was reopened the following day through Waihee (from the north) only.[17]

On August 11, Hawaii Attorney General Anne Lopez announced that her department would conduct a "comprehensive review of critical decision-making and standing policies" surrounding the wildfires.[196]

On August 16, Governor Josh Green announced his intention to create a moratorium on the sale of land damaged and destroyed by the fires. While acknowledging there may be legal challenges to such a moratorium, he asked "please don't approach them with an offer to buy land. Please don't approach their families to tell them that they are going to be better off if they make a deal, because we're not going to allow it."[197]

On August 31, Attorney General Lopez disclosed in an interview that her office had hired UL's Fire Safety Research Institute to conduct an independent investigation on behalf of the state government, and the UL investigators had been on scene on Maui since August 24.[198]

International assistance

[edit]Japan

[edit]Japan pledged $2 million of aid, with $1.5 million given to the American Red Cross and $500,000 given to the Tokyo-based nonprofit organization Japan Platform.[199]

South Korea

[edit]South Korea pledged $2 million of aid in support relief efforts. The pledge included a $1.5 million donation to the Hawai‘i Community Foundation and $500,000 of supplies purchased from local Korean markets.[200][201]

Taiwan

[edit]The Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office in Honolulu announced a $500,000 cash donation to the Hawai‘i Community Foundation to support relief efforts.[202]

Hungary

[edit]A container city on the island of Maui is being built from foldable container units.[203]

Fundraising and donations

[edit]Due to multiple GoFundMe fundraising efforts for those that were affected by the fires, the site put together a hub to gather all of the verified fundraisers, and added that by August 18 there had been more than 250,000 donors and $30 million raised through the site for those affected.[204] Other organizations, communities and businesses across the United States held donation drives and fundraisers where proceeds and the items would be donated to specific nonprofits or groups.[205][206] All twelve professional sports teams from the Los Angeles area donated $450,000 to relief efforts.[207] In addition, proceeds from the October 8 preseason game at the Stan Sheriff Center in Honolulu between the Los Angeles Clippers and the Utah Jazz will go towards the Maui Strong Fund.[208]

The Hawaiian Mission Houses Archives has uploaded items to their digitization project relevant to Lahaina's history such as photos, journals, drawings, and letters to aid in the recovery of historic sites.[209]

Concerns about preparedness

[edit]A lack of adequate warning and preparation has also come into focus.[210] Despite Hawaii's advanced integrated outdoor siren warning system, on Maui, 80 of these sirens, designed for tsunamis and other disasters, remained silent as the fires burned. The Hawaii Emergency Management Agency attributed the lack of activation to the fires' rapid progression and existing ground response coordination. And while residents received other alerts, such as mobile phone notifications, the intensity and urgency of these messages were deemed insufficient.[211][212][213] At least one analyst compared them unfavorably to high-priority tsunami warnings, suggesting a possible alarm fatigue among residents, where frequent, less urgent alerts can diminish the perceived significance of real threats.[213] The administrator of the Maui County Emergency Management Agency, Herman Andaya, defended the decision not to activate the emergency sirens in an August 16 press conference; he argued that the outdoor sirens exist only on the coastline and are normally used to warn residents to flee tsunamis by heading to the mountainside, which would have sent them straight into the fire.[214] Andaya resigned the next day effective immediately, citing health reasons.[215]

The Lahaina wildfires also exposed gaps in the state's wildfire preparedness. In a 2021 report, Hawaii officials ranked wildfire risk as "low" despite increasing fire acreage and dangers from drought and non-native grasses. The report criticized inadequate funding and lack of fire prevention strategies. Previous wildfires served as a warning, but risks were not adequately addressed. Hawaii's fire management budgets had not kept pace with growing threats, according to the Hawaii Wildfire Management Organization. Non-native, flammable grasses remained widespread, increasing fire risk. The climatologist Abby Frazier emphasized Hawaii's extreme wildfire vulnerability and called for more serious fire prevention efforts. The 2021 Maui County report had recommended fire hazard risk assessment and replacing non-native grasses, but it is unclear if these recommendations were implemented.[216][217]

A state official for the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources delayed the request of the release of water by the West Maui Land Co. to protect its holdings until it was too late.[218] In early September, it was reported that residents of numerous communities around the state of Hawaii had become deeply worried about the risk of losing their own homes to wildfires, after seeing how Lahaina had been so suddenly destroyed.[219][220]

New warning programs

[edit]In July 2024, Hawaiian Electric implemented its first public safety power shutoff plan (PSPS) by identifying fire-prone areas on each island whose history of fires, winds, dry vegetation levels and other factors put them at risk. A PSPS might be issued because of drought, high winds (40-50 mph) and low humidity by broadcasting messages on the PSPS at least 24 hrs. in advance.[221] In the rest of the US wildfire vulnerable areas, particularly in California, PSPS plans have been implemented .[222] Hawaiian Electric also began the installation of 52 weather stations on four islands: 23 on Maui, 15 on Hawai’i Island, 12 on O‘ahu and two on Moloka‘I in fire- susceptible areas to more effectively predict and react to wildfires. The solar-powered stations provide temperature, humidity and wind data that will help determine whether the utility should actuate a public safety power shutoff (PSPS). The meteorological data will be shared with the National Weather Service and other weather forecasters to better predict fire risks state-wide. About half of the $1.7 million invested in the project will be paid through the US Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.[223]

Conspiracy theories

[edit]Following the fires, a variety of conspiracy theories about them were posted to social media, notably by far-right conspiracy theorist Stew Peters. Some contained doctored images or images and videos of other unrelated events presented as being from the fires, often ostensibly demonstrating that a directed-energy weapon or "space laser" was involved.[224][225][226][227] There have also been mentions of famous individuals' estates in Hawaii that have not been damaged from the fires, prompting unsubstantiated accusations of blame.[228] Other posts have claimed that wildfires do not occur naturally or that vegetation is not left standing in a natural fire.[229][230] Real Raw News, a fake news website, promoted falsehoods about U.S. Marines attacking a FEMA convoy fleeing the wildfires[231][232] and arresting FEMA deputy administrator Erik Hooks.[233]

Researchers from Microsoft, Recorded Future, the RAND Corporation, NewsGuard and the University of Maryland found that a Chinese government-directed disinformation campaign used the disaster to attempt to sow discord in the US.[234] Lahaina residents were discouraged from going to the agencies for assistance by disinformation from people who regularly spread Russian propaganda.[235]

See also

[edit]- 2023 Canadian wildfires

- 2023 Greece wildfires

- List of wildfires in the United States

- Wildfires in the United States

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "FIRMS US/Canada". Fire Information for Resource Management System US/Canada. NASA. Archived from the original on August 11, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Lahaina Wildfire Death Toll Now At 102". Honolulu Civil Beat. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ a b Daily Operations Briefing Thursday, August 17, 2023 8:30 a.m. ET FEMA National Watch Center (PDF) (Report). Federal Emergency Management Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Maui police confirm identity of 101st wildfire victim, a 76-year-old who boated from California in the 1970s". Fox News. The Associated Press. February 14, 2024. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Pacific Disaster Center and the Federal Emergency Management Agency releases Fire Damage. County of Maui (Report). August 12, 2023. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ a b National Centers for Environmental Information; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (September 11, 2023). "U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters 1980-2023" (PDF). NOAA NCEI Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters. United States Department of Commerce. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 11, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Bogel-Burroughs, Nicholas; Kovaleski, Serge F.; Hubler, Shawn; Mellen, Riley (August 15, 2023). "How Fire Turned Lahaina Into a Death Trap". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Sacks, Brianna (August 15, 2023). "Power lines likely caused Maui's first reported fire, video and data show". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 15, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ^ a b Mike Baker; Glenn Thrush (October 2, 2024). "Lahaina Inferno Emerged From Smoldering Remnants of Quelled Fire". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Spectrum News Staff. "Hawaii Island police investigate arson as cause of the Kaʻū wildfire". Spectrum News. Archived from the original on September 2, 2023. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ a b Shalvey, Kevin; Arancio, Victoria; El-Bawab, Nadine; Deliso, Meredith (August 9, 2023). "'I was trapped': Maui fire survivors speak out as emergency declared". [[ABC News]]. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "Office of the Governor – News Release – Emergency Proclamation for Maui Air Travel and Hurricane Dora". governor.hawaii.gov. Archived from the original on August 9, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ Alvarez, Priscilla; Klein, Betsy (August 10, 2023). "Biden says 'every asset that we have will be available' to Hawaii residents affected by wildfires". CNN. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "August 11, 2023 Maui wildfire news". CNN. August 12, 2023. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Rush, Claire; Dupuy, Beatrice; Sinco Kelleher, Jennifer (August 12, 2023). "Death toll from Maui wildfire reaches 89, making it the deadliest in the US in more than 100 years". Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Pacific Disaster Center and the Federal Emergency Management Agency releases Fire Damage". County of Maui. August 12, 2023. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "'Indescribable grief': Loved ones identify family of 4 killed while fleeing Lahaina wildfire". Hawaii News Now. August 12, 2023. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "Death toll from Maui fires rises to 53, governor says, and more than 1,000 structures have burned". Associated Press. August 10, 2023. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "Maui County raises death toll to 55". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. August 10, 2023. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ a b Rush, Claire; Dupuy, Beatrice; Sinco Kelleher, Jennifer (August 12, 2023). "As death toll from Maui fire reaches 93, authorities say effort to count the losses is just starting". Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ Roy, David P.; De Lemos, Hugo; Huang, Haiyan; Giglio, Louis; Houborg, Rasmus; Miura, Tomoaki (December 1, 2024). "Multi-resolution monitoring of the 2023 maui wildfires, implications and needs for satellite-based wildfire disaster monitoring". Science of Remote Sensing. 10: 100142. Bibcode:2024SciRS..1000142R. doi:10.1016/j.srs.2024.100142. ISSN 2666-0172.

- ^ a b Fuller, Thomas (August 9, 2023). "Maui Town Is Devastated By Deadliest Wildfire to Strike Hawaii". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 9, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ a b Gomes, Andrew (July 13, 2019). "Shuttered plantations' fallow land poses huge risk of fires". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Archived from the original on September 16, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Wessendorf, Cynthia (November 11, 2022). "Why Hawai'i's Wildfires Are Growing Bigger and More Intense". Hawaii Business Magazine. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ Anguiano, Dani (August 10, 2023). "Hawaii wildfires: how did the deadly Maui fire start and what caused it? Rapidly moving fires that exploded on Tuesday night on the island of Maui have killed dozens and displaced thousands". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Bush, Evan (August 17, 2023). "Left unchecked, Maui's nonnative grasses turned into wildfire fuel". NBC News. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c Frosch, Dan; Elinson, Zusha; Carlton, Jim; Mai-Duc, Christine (August 25, 2023). "Everybody Knew the Invasive Grass of Maui Posed a Deadly Fire Threat, but Few Acted". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 25, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ California Public Resources Code Section 4291 Archived March 30, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Jones, Judson (August 10, 2023). "Hawaii Wildfires: Update from Judson Jones". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Ramirez, Rachel (August 9, 2023). "Why did the Maui fire spread so fast? Drought, nonnative species and climate change among possible reasons". CNN. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ Klein, Naomi; Sproat, Kapuaʻala (August 17, 2023). "Why was there no water to fight the fire in Maui?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Frosch, Dan; Carlton, Jim (August 12, 2023). "Hawaii Officials Were Warned Years Ago That Maui's Lahaina Faced High Wildfire Risk". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 11, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023. All times are from the infographic included in the cited article.

- ^ Pickett, Elizabeth; Grossman, Ilene (2014). Western Maui Community Wildfire Protection Plan (PDF). Kamuela, Hawaii: Hawaii Wildfire Management Organization. p. 55. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 15, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ Maui Emergency Management Agency (August 2020). Hazard Mitigation Plan Update (Report). County of Maui, Hawai'i. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "National Significant Wildland Fire Potential Outlook: Outlook Period – August through November 2023" (PDF). National Interagency Fire Center. August 1, 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 4, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ "State of Hawai'i Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan - Base Plan" (PDF). February 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ Gordon, Isabelle; Chapman, Scott; Bronstein, Casey; Tolan, Allison (August 11, 2023). "Hawaii underestimated the deadly threat of wildfire, records show". CNN. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ a b O’Leary, Maureen (November 28, 2023). "2023 Atlantic hurricane season ranks 4th for most-named storms in a year". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

The strong gradient between a high pressure system to the north and Dora to the south was a contributing factor to the wind-driven, fast-moving wildfires in Hawaii.

- ^ Iati, Marisa; Dance, Scott; Hassan, Jennifer (August 9, 2023). "Wildfires burning in Hawaii, fanned by intense winds, force evacuations". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 9, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ Ramos, Alexandre M.; Russo, Ana; DaCamara, Carlos C.; Nunes, Silvia; Sousa, Pedro; Soares, P. M. M.; Lima, Miguel M.; Hurduc, Alexandra; Trigo, Ricardo M. (March 17, 2023). "The compound event that triggered the destructive fires of October 2017 in Portugal". iScience. 26 (3): 106141. Bibcode:2023iSci...26j6141R. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2023.106141. ISSN 2589-0042. PMC 10006635. PMID 36915678.

- ^ Henson, Bob; Masters, Jeff (August 10, 2023). "What caused the deadly Hawai'i wildfires? » Yale Climate Connections". Yale Climate Connections. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ @pppapin (August 10, 2023). "Plenty of media talking #Hurricane #Dora influence on #MauiFires, so worth a deep dive quantifying overall TC impact by removing vortex. Result Dora played a *very* minor role, slightly enhancing low-level flow over Maui at fire initiation time" (Tweet). Retrieved August 15, 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ a b US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "Text Products for AFD Issued by HFO". forecast.weather.gov. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "Text Products for AFD Issued by HFO". forecast.weather.gov. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ a b Upcountry Maui Is Entering The Next Phase Of Fire Recovery. But Anxiety Persists Honolulu Civil Beat

- ^ 9/25 Maui Wildfire Disaster Update Archived September 29, 2023, at the Wayback Machine mauicounty.gov. Maui County.

- ^ 9/14 Maui Wildfire Disaster Update Archived September 29, 2023, at the Wayback Machine mauicounty.gov. Maui County.

- ^ 9/03 Maui Wildfire Disaster Update Archived September 4, 2023, at the Wayback Machine mauicounty.gov. Maui County.

- ^ 9/02 Maui Wildfire Disaster Update Archived September 5, 2023, at the Wayback Machine mauicounty.gov. Maui County.

- ^ "8/25 County of Maui Wildfire Disaster Update". mauicounty.gov. Maui County. Archived from the original on August 26, 2023. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ "WFIGS 2023 Interagency Fire Perimeters to Date". National Interagency Fire Center. Archived from the original on September 9, 2023. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ^ "2 Oahu brush fires contained after burning 250 acres". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. August 4, 2023. Archived from the original on August 5, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "Multiple blazes, including 2 brush fires, keep Oahu fire crews busy". Hawaii News Now. August 4, 2023. Archived from the original on August 7, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ NWS Honolulu (August 7, 2023). "Red Flag Warning". Iowa Environmental Mesonet. Iowa State University. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Tanji, Melissa; Thayer, Matthew (August 9, 2023). "Maui on fire: Fierce winds fuel damaging fires in Lahaina, Upcountry". The Maui News. Archived from the original on August 9, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Landing operations at Kahului Airport back to normal after brush fire Archived August 12, 2023, at the Wayback Machine Hawaii News Now

- ^ Flights landing at Maui's airport while MFD fights nearby fire Archived August 12, 2023, at the Wayback Machine KHON-TV

- ^ "On Friday, August 4th, 2023... - Maui County Fire Department". Maui County Fire Department. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023 – via Facebook.

- ^ "SFO reports Hawaii fires causing handful of flight delays - CBS San Francisco". CBS News. August 9, 2023. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ Kalahele, Kiana (August 8, 2023). "More than 30 downed power poles reported on Maui; thousands without power". Hawaii News Now. Archived from the original on August 11, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Sacks, Brianna (August 12, 2023). "Hawaii utility faces scrutiny for not cutting power to reduce fire risks". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "Fire Department advising immediate proactive evacuation of residents of Pi'iholo and Olinda roads". County of Maui. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

With the potential risk of escalating conditions from an Upcountry brush fire, the Fire Department is strongly advising residents of Piʻiholo and Olinda roads to proactively evacuate.

- ^ "County of Maui - Shortly after midnight this morning a..." County of Maui. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023 – via Facebook.

- ^ a b County of Maui [@countyofmaui] (March 12, 2023). "The Pacific Disaster Center (PDC) and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) released the following damage assessment maps from multiple wildfires in Maui County" – via Instagram.

- ^ Baker, Mike (August 12, 2023). "Hawaii Wildfires: Update from Mike Baker". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ Yan, Holly; Maxouris, Christina; Jackson, Amanda; Lynch, Jamiel (August 9, 2023). "'It's apocalyptic': People jump into the ocean to flee Maui wildfires as patients overwhelm hospitals and 911 gets cut off". CNN. Archived from the original on August 9, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c Sinco Kelleher, Jennifer; McAvoy, Audrey; Weber, Christopher (August 9, 2023). "Wildfire on Maui kills at least 6, damages over 270 structures as it sweeps through historic town". Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 9, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ a b "Much of historic Lahaina town believed destroyed as huge wildfire sends people fleeing into water". Hawaii News Now. August 9, 2023. Archived from the original on August 9, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ Bogel-Burroughs, Nicholas; Kovaleski, Serge F.; Hubler, Shawn; Mellen, Riley (August 15, 2023). "How Fire Turned Lahaina Into a Death Trap". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 15, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Bogel-Burroughs, Nicholas; Kovaleski, Serge F.; Hubler, Shawn; Mellen, Riley (August 15, 2023). "How Fire Turned Lahaina Into a Death Trap". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c d DiFeliciantonio, Chase; Parker, Jordan (August 11, 2023). "Maui fire: Questions raised if officials reacted quickly enough to save residents". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "Lahaina fire declared 100% contained; water conservation urged due to power outages". County of Maui. August 8, 2023. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

Maui Fire Department declared the Lahaina brush fire 100% contained shortly before 9 a.m. today.

- ^ a b c d Lin, Rong-Gong; Petri, Alexandra E.; Winton, Richard (August 11, 2023). "Chaos and terror: Failed communications left Maui residents trapped by fire. Scores died". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "Maui fire timeline and warnings: Forecast through engulfment". KHON2. August 17, 2023. Archived from the original on August 22, 2023. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- ^ "Maui Hawaii Fire Imagery". storms.ngs.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- ^ Video shows family's terrifying escape from Maui wildfires | CNN, August 12, 2023, archived from the original on August 14, 2023, retrieved August 14, 2023

- ^ Baker, Mike; Browning, Kellen; Bogel-Burroughs, Nicholas (August 13, 2023). "As Inferno Grew, Lahaina's Water System Collapsed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ Samuel, Henry (August 12, 2023). "Exploding cars and bodies in the harbour: How Hawaii's inferno chased holidaymakers into the sea". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ Slater, Joanna (August 12, 2023). "After 5 hours in ocean, Maui fire survivor feels 'blessed to be alive'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ Sanchez, Ray (August 12, 2023). "Hawaii has a robust emergency siren warning system. It sat silent during the deadly wildfires". CNN. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ Bogel-Burroughs, Nicholas; Albeck-Ripka, Livia; Mayorquin, Orlando (August 10, 2023). "Some in Lahaina Say Maui Fires Reached Them Before Evacuation Orders". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ Rebecca Boone; Jennifer Sinco Kelleher; Audrey Mcavoy-Associated Press (August 15, 2023). "In deadly Maui wildfires, communication failed. Chaos overtook Lahaina along with the flames". KITV Island News. Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ^ Petri, Alexandra E.; Winton, Richard; Dolan, Jack; Kaleem, Jaweed; Lin, Summer (August 11, 2023). "Death toll in Maui fires rises to 67, expected to climb". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "Losses from West Maui fire approach an estimated $6 billion, Hawaii governor says". CNN. August 12, 2023. Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ Schaefers, Allison (August 9, 2023). "Century-old Pioneer Inn among property casualties of West Maui wildfires". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "VIDEO: Lahaina fire fatalities rise to 93; Green said toll will 'continue to climb'". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. August 12, 2023. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ "Hawaii Wildfires: The Latest Developments on Maui". Honolulu Magazine. August 12, 2023. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "Maui fires live updates: Death toll rises as search for missing goes on". NBC News. August 12, 2023. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ Yamamura, Kevin (August 12, 2023). "Hawaii Wildfires: Update from Kevin Yamamura". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "8/24 County of Maui Wildfire Disaster Update". County of Maui. August 24, 2023. Archived from the original on August 29, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- ^ "Maui releases list of hundreds reported missing after Lahaina fire". Hawaii News Now. HNN Staff. August 25, 2023. Archived from the original on August 26, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ "MPD Requests Public To File Unaccounted For Missing Person Report". County of Maui. September 4, 2023. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ Number of Missing in Maui Wildfires Drops to 66, from Hundreds Archived September 9, 2023, at the Wayback Machine The New York Times

- ^ MPD/FBI Credible List of Unaccounted For Individuals (9/15/2023) Archived September 20, 2023, at the Wayback Machine Maui Police Department

- ^ a b c "First of thousands of Lahaina residents return to homes destroyed by deadly wildfire". The Associated Press. Lahaina, Hawaii. September 26, 2023. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Victoria Lozano, Alicia (September 25, 2023). "Maui residents get a close-up look at the burn scar where their homes once stood". ABC News. Lahaina, Hawaii. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Clark, Cammy (August 13, 2023). "Lāhainā Fire deadliest US wildfire since Cloquet blaze in 1918; death toll likely to rise". Big Island Now. Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ "Death toll from Maui wildfires rises to 89, officials say". The Washington Post. August 12, 2023. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "Hawaii responds as deadly wildfires across 2 islands destroy communities". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. August 9, 2023. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Kaanapali flare up now 100% contained, Mayor Bissen said Archived August 12, 2023, at the Wayback Machine KITV

- ^ Fire prompts evacuations in West Maui community of Kaanapali Archived August 12, 2023, at the Wayback Machine NBC News

- ^ "New Maui brush fire forces brief evacuation of Lahaina neighborhood". CBS News. August 26, 2023. Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ a b "Hawaii island battling new fire in Kau, along with 3 blazes in Kohala". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. August 9, 2023. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Death toll from Maui fires rises to 53, governor says, and more than 1,000 structures have burned". Maui News. August 10, 2023. Archived from the original on August 11, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "HFD responds to large brushfire in Wahiawa". KITV. August 16, 2023. Archived from the original on August 17, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ USGS (September 4, 2009), PAGER-CAT Earthquake Catalog, Version 2008_06.1, United States Geological Survey, archived from the original on July 17, 2020, retrieved August 3, 2018

- ^ Sommerlad, Joe (August 11, 2023). "A brief history of natural disasters in Hawaii, from tsunamis to wildfires". The Independent. Archived from the original on August 11, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ Thebault, Reis; Brulliard, Karin; Slater, Joanna (August 11, 2023). "Hawaii's worst fires leave Lahaina in ruins as death toll rises to 53". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on August 11, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ Carli, Lorraine (August 12, 2023). "Maui wildfire one of deadliest in US history". National Fire Protection Association. Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ Rogers, Paul (November 22, 2018). "Camp Fire is deadliest U.S. wildfire in 100 years; eerily similar to 1918 inferno that killed 453". East Bay Times. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ "Press Releases". County of Maui. Archived from the original on September 5, 2023. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "County of Maui provides update on individuals still unaccounted for". Maui County. Archived from the original on September 19, 2023. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ "County of Maui releases validated list of names of individuals who remain unaccounted for following". Maui County. Archived from the original on October 5, 2023. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ "Hawaii officials say DNA tests drop Maui fire death count to 97". Abc27. September 18, 2023. Archived from the original on October 5, 2023. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

further testing showed they had multiple DNA samples from some of the victims

- ^ "MPD Press Releases". County of Maui. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ Fortin, Jacey; Hassan, Adeel. "As Search for Maui Victims Goes On, Names of Dead Slowly Emerge". The New York Times. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ "Identities of Maui Wildfire Disaster Victims". County of Maui. September 17, 2023. Archived from the original on September 18, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ Debusmann Jr, Bernd (August 16, 2023). "Hawaii wildfires: Why identifying the victims could take years". BBC News. Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ^ "One Filipino among fatalities in Hawaii wildfire – DFA". The Philippine Star. August 18, 2023. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- ^ Hoffman, Riley (August 11, 2023). "Maui fire deadliest natural disaster in state's history". ABC News. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "Fires on Hawaii's Maui island kill at least 6 as blazes force people to flee flames". CBS News. August 9, 2023. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "Maui wildfire miracle with 60 survivors found in single home as death toll hits 111". The Independent. August 17, 2023. Archived from the original on August 17, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ Fortin, Jacey; Hassan, Adeel (August 9, 2024). "Death Toll of Maui Wildfire Now at 102" – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Hu, Alex (October 25, 2023). "Maui's Herculean Task". City Journal. Archived from the original on October 17, 2023. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Blair, Chad (August 17, 2023). "Hawaii Governor Commits To Rebuild Lahaina For Local Residents First". Honolulu Civil Beat. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ Foster, Lauren (August 17, 2023). "Maui Wildfire Losses Mount. Homeowners in Every State Will Pay a High Price". Barron's. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Corkery, Michael; Cowan, Jill (August 10, 2023). "Maui Had a Housing Shortage Even Before the Wildfires". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hurley, Timothy (August 10, 2023). "Lahaina's historic and cultural treasures go up in smoke". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c Hurley, Timothy (August 11, 2023). "Maria Lanakila still stands, but Waiola Church is gone". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Archived from the original on August 11, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Hubler, Shawn (August 10, 2023). "The historic town of Lahaina, and its legacy, is in ashes smoke". Archived from the original on August 11, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ "CNN Live Updates: Maui Wildfires". CNN. August 9, 2023. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Boyette, Holly; Yan, Amanda; Jackson, Jamiel; Lynch, Chris (August 9, 2023). "At least 6 dead as Maui wildfires overwhelm hospitals, sever 911 services and force people to flee into the ocean". CNN. Archived from the original on August 9, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ "Maui Invitational Partners with Allstate". Allstate Maui Invitational.

- ^ Truesdale, Jack; Heaton, Thomas (August 10, 2023). "Lahaina Emerges From 'Devastating' Fire As Relief Begins To Arrive". Honolulu Civil Beat. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ 081123 Lahaina, HI-Oldest Banyan tree burnt, crispy officials try watering.mp4, August 11, 2023, archived from the original on August 13, 2023, retrieved August 13, 2023

- ^ "Unsafe Water Advisory for Lahaina Water System". County of Maui. August 11, 2023. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

The Lahaina water system experienced wildfire impacts and may have fire related contamination […] DO NOT DRINK-DO NOT BOIL YOUR WATER Failure to follow this advisory could result in illness.

- ^ "Unsafe water advisory issued for Upper Kula and Lahaina areas affected by wildfires". County of Maui. August 11, 2023. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "Unsafe Water Advisory for Upper Kula Water System potentially affected areas". County of Maui. August 12, 2023. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ "Maui County: Tap water unsafe to drink in some areas". Hawaii News Now. August 11, 2023. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "Potable water tanker locations for Upcountry and West Maui". County of Maui. August 9, 2023. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ Canon, Gabrielle (August 18, 2023). "'Coral are going to die': Maui wildfires take toxic toll on marine ecology". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ Napuunoa, Nicole; Ufi, Elizabeth; Rodriguez, Max; Lopez, Lucy (August 8, 2023). "Effects from Maui fires felt deeply across islands". KHON2. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ Sangal, Aditi; Powell, Tori B; Meyer, Matt; Hammond, Elise; Lau, Chris; Raine, Andrew (August 11, 2023). "Live updates: Maui wildfires death toll rises, Lahaina 80% destroyed". CNN. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "Lahaina, Pulehu and Upcountry Maui Fires Update No. 20, 2:05 a.m." County of Maui. August 12, 2023. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ "Over 1,400 in emergency shelters on Maui as hundreds more displaced residents seek shelter elsewhere". Hawaii News Now. August 12, 2023. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ "SF Mayor London Breed among Bay Area travelers impacted by devastating Hawaii wildfires". ABC7 San Francisco. August 10, 2023. Archived from the original on August 11, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Josephs, Leslie (August 11, 2023). "Airlines add flights to get travelers off of Maui after deadly wildfires". CNBC. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "Hawaiian Air adds flights, offers $19 fares as visitor evacuations from Maui continue". Hawaii News Now. August 9, 2023. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ Leff, Gary (August 9, 2023). "Southwest Airlines Running $19 Flights From Maui, $1 Pet Fares As Lahaina Burns Down". View from the Wing. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.