Rifaximin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Xifaxan, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604027 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | < 0.4% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 6 hours |

| Excretion | Fecal (97%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.111.624 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

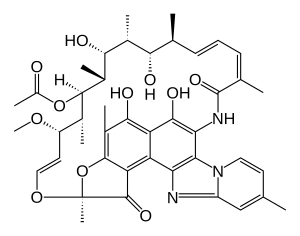

| Formula | C43H51N3O11 |

| Molar mass | 785.891 g·mol−1 |

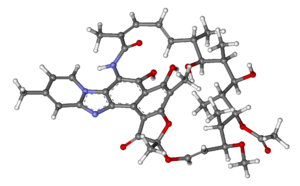

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 200 to 205 °C (392 to 401 °F) (dec.) |

| |

| |

| | |

Rifaximin, sold under the brand name Xifaxan among others, is a non-absorbable, broad-spectrum antibiotic mainly used to treat travelers' diarrhea. It is based on the rifamycin antibiotics family. Since its approval in Italy in 1987, it has been licensed in more than 30 countries for the treatment of a variety of gastrointestinal diseases like irritable bowel syndrome and hepatic encephalopathy. It acts by inhibiting RNA synthesis in susceptible bacteria by binding to the RNA polymerase enzyme. This binding blocks translocation, which stops transcription.[4] It was developed by Salix Pharmaceuticals.[3][5][6]

Medical uses

[edit]Travelers' diarrhea

[edit]Rifaximin is used to treat travelers' diarrhea caused by E. coli bacteria in people aged twelve years of age and older. It treats travelers' diarrhea by stopping the growth of the bacteria that cause diarrhea. Rifaximin will not work to treat travelers' diarrhea that is bloody or occurs with fever.[7]

Irritable bowel syndrome

[edit]Rifaximin is used for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). It possesses anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties, and is a non-absorbable antibiotic that acts locally in the gut. These properties make it efficacious in relieving chronic functional symptoms of non-constipation type irritable bowel syndrome.[8] It appears to retain its therapeutic properties for this indication, even after repeated courses.[9][10] It is particularly indicated where small intestine bacterial overgrowth is suspected of involvement in irritable bowel syndrome. Symptom relief or improvement can be obtained for global irritable bowel syndrome symptoms, including: abdominal pain, flatulence, bloating, and stool consistency. A drawback is that repeated courses may be necessary for relapse of symptoms.[10][11]

Clostridioides difficile infection

[edit]Rifaximin may also be a useful addition to vancomycin when treating people with relapsing C. difficile infection.[12][13] However, the quality of evidence of these studies was judged to be low.[14] Because exposure to rifamycins in the past may increase risk for resistance, rifaximin should be avoided in such cases.[15]

Hepatic encephalopathy

[edit]Rifaximin is used to prevent episodes of hepatic encephalopathy (changes in thinking, behavior, and personality caused by a build-up of toxins in the brain in adults who have liver disease). It treats hepatic encephalopathy by stopping the growth of bacteria that produce toxins and that may worsen the liver disease. Although high-quality evidence is lacking, it appears to be as effective as, or more effective than, other available treatments for hepatic encephalopathy (such as lactulose), is better tolerated, and may work faster.[11][16] It prevents reoccurring encephalopathy and is associated with high patient satisfaction. People are more compliant and satisfied to take this medication than any other due to minimal side effects, prolonged remission, and overall cost.[17] The drawbacks are increased cost, and lack of robust clinical trials for hepatic encephalopathy without combination lactulose therapy.[18]

Other uses

[edit]Other uses include treatment of: infectious diarrhea, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, inflammatory bowel disease, and diverticular disease.[19][11][20][21] It is effective in treating small intestinal bacterial overgrowth regardless of whether it is associated with irritable bowel syndrome or not.[22] It has also shown efficacy with rosacea, ocular rosacea which also presents as dry eyes for patients with co-occurrence with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).[23]

Special caution

[edit]People should avoid rifaximin if they are allergic to any of rifabutin, rifampin, and rifapentine. It may cause attenuated vaccines (such as typhoid vaccine) not to work well. Health-care professionals should be informed about its usage before receiving immunization.[24] Pregnant or breastfeeding women should avoid rifaximin: it can harm the fetus.[25] Caution is required in people with cirrhosis who have a Child–Pugh score of C.[11]

Side effects

[edit]Rifaximin has an excellent safety profile due to its lack of systemic absorption. Clinical trials did not show any serious adverse events while using rifaximin. There were no deaths while using it in the clinical trials.[9][10][26]

The most common side effects include nausea, stomach pain, dizziness, fatigue, headaches, muscle tightening, and joint pain. It may also cause reddish discoloration of urine.[27]

The most serious side effects of rifaximin are:

- Clostridioides difficile-associated diarrhea

- Drug-resistant bacterial superinfection

- Severe allergic reactions including hives, rashes and itching

Interactions

[edit]As rifaximin is not significantly absorbed from the gut, the great majority of this drug's interactions are negligible in people with healthy liver function, so healthcare providers usually do not worry about drug interactions unless liver impairment is present.[9] It may decrease the effectiveness of warfarin, a commonly prescribed anticoagulant, in people with liver problems.[28]

Pharmacology

[edit]Rifaximin is a semisynthetic broad spectrum antibacterial drug, derived through chemical modification of the natural antibiotic rifamycin.[29] It has very low bioavailability due to its poor absorption after oral administration. Because of this local action within the gut and the lack of horizontal transfer of resistance genes, the development of bacterial resistance is rare, and most of the drug taken orally stays in the gastrointestinal tract where the infection takes place.[30]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Rifaximin interferes with transcription by binding to the β-subunit of bacterial RNA polymerase.[11] This results in the blockage of the translocation step that normally follows the formation of the first phosphodiester bond, which occurs in the transcription process.[31] This in turn results in a reduction of bacteria populations, including gas-producing bacteria, which may reduce mucosal inflammation, epithelial dysfunction, and visceral hypersensitivity. Rifaximin has broad spectrum antibacterial properties against both gram positive and gram negative anaerobic and aerobic bacteria. As a result of bile acid solubility, its antibacterial action is limited mostly to the small intestine and less so the colon.[11] A resetting of the bacterial composition has also been suggested as a possible mechanism of action for relief of irritable bowel syndrome symptoms.[32] Additionally, rifaximin may have a direct anti-inflammatory effect on gut mucosa via modulation of the pregnane X receptor.[32] Other mechanisms for its therapeutic properties include inhibition of bacterial translocation across the epithelial lining of the intestine, inhibition of adherence of bacteria to the epithelial cells, and a reduction in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines.[33]

Availability

[edit]In the United States, Salix Pharmaceuticals holds a US Patent for rifaximin and markets it under the brand name Xifaxan.[3] In addition to receiving FDA approval for travelers' diarrhea and (marketing approved for)[34] hepatic encephalopathy, rifaximin received FDA approval for irritable bowel syndrome in May 2015.[35] No generic formulation is available in the US and none has appeared due to the fact that the FDA approval process was ongoing. If rifaximin receives full FDA approval for hepatic encephalopathy it is likely that Salix will maintain marketing exclusivity and be protected from generic formulations until 24 March 2017.[34] In 2018, a patent dispute with Teva was settled which delayed a generic in the United States, with the patent set to expire in 2029.[36]

Rifaximin is approved in many countries for GI disorders.[37] In August 2013, Health Canada issued a Notice of Compliance to Salix Pharmaceuticals for the drug product Zaxine.[38] In India, it is available under the brand names Ciboz and Xifapill.[39][40] In Russia and Ukraine the drug is sold under the name Alfa Normix (Альфа Нормикс), and under the name Flonorm in Mexico, produced by Alfa Wassermann S.p.A. (Italy).[41] In 2018, the FDA approved a similar drug by Cosmos Pharmaceuticals called Aemcolo for traveler's diarrhea.[42]

In January 2025, The FDA granted tentative approval to an abbreviated new drug application for a generic of Bausch Health's Xifaxan (rifaximin).[43]

References

[edit]- ^ "Rifaximin international". Drugs.com. 2 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ "Product monograph brand safety updates". Health Canada. February 2024. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Xifaxan- rifaximin tablet". DailyMed. 1 October 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Koo HL, DuPont HL (January 2010). "Rifaximin: a unique gastrointestinal-selective antibiotic for enteric diseases". Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 26 (1): 17–25. doi:10.1097/MOG.0b013e328333dc8d. PMC 4737517. PMID 19881343.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Xifaxan (Nfaximin) NDA #021361". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Xifaxan (rifaximin) NDA #022554". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 26 July 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ DuPont HL (July 2007). "Therapy for and prevention of traveler's diarrhea". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 45 (Suppl 1): S78 – S84. doi:10.1086/518155. PMID 17582576.

- ^ Kane JS, Ford AC (2016). "Rifaximin for the treatment of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome". Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 10 (4): 431–442. doi:10.1586/17474124.2016.1140571. PMID 26753693. S2CID 13607138.

- ^ a b c Ponziani FR, Pecere S, Lopetuso L, Scaldaferri F, Cammarota G, Gasbarrini A (July 2016). "Rifaximin for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome - a drug safety evaluation". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 15 (7): 983–991. doi:10.1080/14740338.2016.1186639. PMID 27149541. S2CID 25426888.

- ^ a b c Song KH, Jung HK, Kim HJ, Koo HS, Kwon YH, Shin HD, et al. (April 2018). "Clinical Practice Guidelines for Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Korea, 2017 Revised Edition". Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 24 (2): 197–215. doi:10.5056/jnm17145. PMC 5885719. PMID 29605976.

- ^ a b c d e f Iorio N, Malik Z, Schey R (2015). "Profile of rifaximin and its potential in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome". Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology. 8: 159–167. doi:10.2147/CEG.S67231. PMC 4467648. PMID 26089696.

- ^ Johnson S, Schriever C, Galang M, Kelly CP, Gerding DN (March 2007). "Interruption of recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea episodes by serial therapy with vancomycin and rifaximin". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 44 (6): 846–848. doi:10.1086/511870. PMID 17304459.

- ^ Garey KW, Ghantoji SS, Shah DN, Habib M, Arora V, Jiang ZD, et al. (December 2011). "A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study to assess the ability of rifaximin to prevent recurrent diarrhoea in patients with Clostridium difficile infection". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 66 (12): 2850–2855. doi:10.1093/jac/dkr377. PMID 21948965.

- ^ Nelson RL, Suda KJ, Evans CT (March 2017). "Antibiotic treatment for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (3): CD004610. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004610.pub5. PMC 6464548. PMID 28257555.

- ^ Huang JS, Jiang ZD, Garey KW, Lasco T, Dupont HL (June 2013). "Use of rifamycin drugs and development of infection by rifamycin-resistant strains of Clostridium difficile". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 57 (6): 2690–2693. doi:10.1128/AAC.00548-13. PMC 3716149. PMID 23545528.

- ^ Lawrence KR, Klee JA (August 2008). "Rifaximin for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy". Pharmacotherapy. 28 (8): 1019–1032. doi:10.1592/phco.28.8.1019. PMID 18657018. S2CID 25662917. Free full text with registration at Medscape.

- ^ Kimer N, Krag A, Gluud LL (March 2014). "Safety, efficacy, and patient acceptability of rifaximin for hepatic encephalopathy". Patient Preference and Adherence. 8: 331–338. doi:10.2147/PPA.S41565. PMC 3964161. PMID 24672227.

- ^ Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, Cordoba J, Ferenci P, Mullen KD, et al. (August 2014). "Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver". Hepatology. 60 (2): 715–735. doi:10.1002/hep.27210. PMID 25042402. S2CID 3155213.

- ^ Piccin A, Gulotta M, di Bella S, Martingano P, Crocè LS, Giuffrè M (February 2023). "Diverticular Disease and Rifaximin: An Evidence-Based Review". Antibiotics. 12 (3): 443. doi:10.3390/antibiotics12030443. PMC 10044695. PMID 36978310.

- ^ Bianchi M, Festa V, Moretti A, Ciaco A, Mangone M, Tornatore V, et al. (April 2011). "Meta-analysis: long-term therapy with rifaximin in the management of uncomplicated diverticular disease" (PDF). Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 33 (8): 902–910. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04606.x. PMID 21366632.

- ^ Kruse E, Leifeld L (April 2015). "Prevention and Conservative Therapy of Diverticular Disease". Viszeralmedizin. 31 (2): 103–106. doi:10.1159/000377651 (inactive 9 December 2024). PMC 4789966. PMID 26989379.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2024 (link) - ^ Triantafyllou K, Sioulas AD, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ (2015). "Rifaximin: The Revolutionary Antibiotic Approach for Irritable Bowel Syndrome". Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (3): 186–192. doi:10.2174/1389557515666150722105340. PMID 26202193.

- ^ Weinstock LB, Steinhoff M (May 2013). "Rosacea and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: prevalence and response to rifaximin". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 68 (5): 875–876. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.11.038. PMID 23602178.

- ^ "Rifaximin Oral: Uses, Side Effects, Interactions, Pictures, Warnings & Dosing - WebMD". www.webmd.com. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ Mahadevan U (August 2006). "Fertility and pregnancy in the patient with inflammatory bowel disease". Gut. 55 (8): 1198–1206. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.078097. PMC 1856272. PMID 16849349.

- ^ Robertson KD, Nagalli S (2022), "Rifaximin", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32966000, retrieved 28 June 2022

- ^ "Rifaximin Side Effects". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Hoffman JT, Hartig C, Sonbol E, Lang M (May 2011). "Probable interaction between warfarin and rifaximin in a patient treated for small intestine bacterial overgrowth". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 45 (5): e25. doi:10.1345/aph.1P578. PMID 21505109. S2CID 12214785.

- ^ Brufani M, Cellai L, Marchi E, Segre A (December 1984). "The synthesis of 4-deoxypyrido[1',2'-1,2]imidazo[5,4-c]rifamycin SV derivatives". The Journal of Antibiotics. 37 (12): 1611–1622. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.37.1611. PMID 6526730.

- ^ Taylor DN (December 2005). "Poorly absorbed antibiotics for the treatment of traveler's diarrhea". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 41 (Supplement_8): S564 – S570. doi:10.1086/432953. PMID 16267720.

- ^ "Rifaximin". DrugBank. 22 March 2017.

- ^ a b Pimentel M (January 2016). "Review article: potential mechanisms of action of rifaximin in the management of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 43 (Suppl 1): 37–49. doi:10.1111/apt.13437. PMID 26618924.

- ^ Lee KJ (October 2015). "Pharmacologic Agents for Chronic Diarrhea". Intestinal Research. 13 (4): 306–312. doi:10.5217/ir.2015.13.4.306. PMC 4641856. PMID 26576135.

- ^ a b "Product Details for NDA 022554". Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

- ^ "FDA approves two therapies to treat IBS-D" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Linnane C. "Bausch Health stock soars 8.6% premarket on news of patent settlement". MarketWatch. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ "Investors | Salix Pharmaceuticals". Salix Pharmaceuticals.

- ^ "Zaxine product information". health-products.canada.ca. 7 November 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ "Brands". Zydus Healthcare Limited. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "Trade Marks Journal" (PDF). The Government of India, Trade Mark Registry. 20 March 2017.

- ^ "Alfa Normix". Russian medical server.

- ^ "Cosmo to give Bausch Health a run for its money with FDA nod for Xifaxan rival". FiercePharma. 20 November 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ "MSN". www.msn.com. Retrieved 17 January 2025.