Yalda Night

| Yalda/Chellé Night | |

|---|---|

Table of Chelle Night | |

| Observed by | |

| Significance | Longest night of the year in Northern Hemisphere[rs 1] |

| Date | December 21 (20 in leap year) |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Yule, Nowruz, Tirgan, Chaharshanbe Suri |

| Yaldā/Chella | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | |

| Reference | 01877 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2022 (17th session) |

| List | Representative |

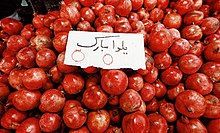

Yaldā Night (Persian: شب یلدا, romanized: shab-e yaldâ or Chelle Night (also Chellah Night, Persian: شب چلّه, romanized: shab-e chelle) is an ancient festival in Iran,[1] Afghanistan,[2] Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan that is celebrated on the winter solstice.[3] This corresponds to the night of December 20/21 (±1) in the Gregorian calendar, and to the night between the last day of the ninth month (Azar) and the first day of the tenth month (Dey)[rs 2] of the Iranian solar calendar.[rs 2]The longest and darkest night of the year is a time when friends and family gather together to eat, drink and read poetry (especially Hafez) and Shahnameh until well after midnight. Fruits and nuts are eaten and pomegranates and watermelons are particularly significant. The red colour in these fruits symbolizes the crimson hues of dawn and the glow of life. The poems of Divan-e Hafez, which can be found in the bookcases of most Iranian families, are read or recited on various occasions such as this festival and Nowruz. Shab-e Yalda was officially added to UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists in December 2022.[4]

Names

[edit]The longest and darkest night of the year marks "the night opening the initial forty-day period of the three-month winter",[rs 1] from which the name Chelleh, "fortieth", derives.[rs 2] There are all together three 40-day periods, one in summer, and two in winter. The two winter periods are known as the "great Chelleh" period (1 Day to 11 Bahman,[rs 2] 40 full days), followed/overlapped by the "small Chelleh" period (10 Bahman to 30 Bahman,[rs 2] 20 days + 20 nights = 40 nights and days). Shab-e Chelleh is the night opening the "big Chelleh" period, that is the night between the last day of autumn and the first day of winter. The other name of the festival, 'Yaldā', is ultimately borrowing from Syriac-speaking Christians.[rs 1][rs 3][rs 4] According to Dehkhoda,[rs 5] "Yalda is a Syriac word meaning birthday, and because people have adapted Yalda night with the nativity of Messiah, it's called the name; however, the celebration of Christmas (Noël) established on December 25, is set as the birthday of Jesus. Yalda is the beginning of winter and the last night of autumn, and it is the longest night of the year". In the first century, significant numbers of Eastern Christians were settled in Parthian and Sasanian territories, where they had received protection from religious persecution.[5] Through them, Iranians (i.e. Parthians, Persians etc.) came in contact with Christian religious observances, including, it seems, Nestorian Christian Yalda, which in Syriac (a Middle Aramaic dialect) literally means "birth" but in a religious context was also the Syriac Christian proper name for Christmas,[rs 6][rs 4][rs 1][rs 3] and which—because it fell nine months after Annunciation—was celebrated on eve of the winter solstice. The Christian festival's name passed to the non-Christian neighbors[rs 4][rs 1][rs 3][rs 5] and although it is not clear when and where the Syriac term was borrowed into Persian, gradually 'Shab-e Yalda' and 'Shab-e Chelleh' became synonymous and the two are used interchangeably.

History

[edit]Yalda Night was one of the holy nights in ancient Iran and included in the official calendar of the Iranian Achaemenid Empire from at least 502 BCE under Darius I. Many of its modern festivities and customs remain unchanged from this period.

Ancient peoples such as the Aryans and Indo-Europeans were well attuned to natural phenomena such as the changing of seasons, as their daily activities were dictated by the availability of sunlight, while their crops were impacted by climate and weather. They found that the shortest days are the last days of autumn and the first night of winter, and that immediately after, the days gradually become longer and the nights shorter. As such, the winter solstice, as the longest night, was called "The night of sun’s birth (Mehr)" and considered to mark the beginning of the year.[6]

The Iranian calendar

[edit]The Iranian (Persian) calendar was founded and framed by Hakim Omar Khayyam.

The history of Persian calendars initially points back to the time when the region of modern-day Persia celebrated their new years according to the Zoroastrian calendar. As Zoroastrianism was then the main religion in the region, their years consisted of "Exactly 365 days, distributed among twelve months of 30 days each plus five special month-less days, known popularly as the ‘stolen ones’, or, in religious parlance, as the ‘five Gatha Days'".[7]

Before the creation of the Solar Hijri calendar, the Jalali calendar was put in place through the order of Sulṭān Jalāl al-Dīn Malikshāh-i Saljūqī in the 5th c. A.H.[8] According to the Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers, “After the death of Yazdigird III (the last king of the Sassanid dynasty), the Yazdigirdī Calendar, as a solar one, gradually lost its position, and the Hijrī Calendar replaced it”.[8]

Yalda Night is celebrated on the winter solstice, the longest and darkest night of the year.

Customs and traditions

[edit]In Zoroastrian tradition the longest and darkest night of the year was a particularly inauspicious day, and the practices of what is now known as "Shab-e Chelleh/Yalda" were originally customs intended to protect people from evil (see dews) during that long night,[rs 7] at which time the evil forces of Ahriman were imagined to be at their peak. People were advised to stay awake most of the night, lest misfortune should befall them, and people would then gather in the safety of groups of friends and relatives, share the last remaining fruits from the summer, and find ways to pass the long night together in good company.[rs 7] The next day (i.e. the first day of Dae month) was then a day of celebration,[note 1] and (at least in the 10th century, as recorded by Al-Biruni), the festival of the first day of Dae month was known as Ḵorram-ruz (joyful day) or Navad-ruz (ninety days [left to Nowruz]).[rs 1] Although the religious significance of the long dark night has been lost, the old traditions of staying up late in the company of friends and family have been retained in Iranian culture to the present day.[9]

References to other older festivals held around the winter solstice are known from both Middle Persian texts as well as texts of the early Islamic period.[rs 1] In the 10th century, Al-Biruni mentions the mid-year festival (Maidyarem Gahanbar) that ran from 11-15 Dae. This festival is generally assumed to have been originally on the winter solstice,[rs 8][rs 9] and which gradually shifted through the introduction of intercalation.cf. [rs 9] Al-Biruni also records an Adar Jashan festival of fire celebrated on the intersection of Adar day (9th) of Adar month (9th), which is the last autumn month.[rs 1] This was probably the same as the fire festival called Shahrevaragan (Shahrivar day of Shahrivar month), which marked the beginning of winter in Tokarestan.[rs 1] In 1979, journalist Hashem Razi theorized that Mehregan — the day-name festival of Mithra that in pre-Islamic times was celebrated on the autumn equinox and is today still celebrated in the autumn — had in early Islamic times shifted to the winter solstice.[rs 10] Razi based his hypothesis on the fact that some of the poetry of the early Islamic era refers to Mihragan in connection with snow and cold. Razi's theory has a significant following on the Internet, but while Razi's documentation has been academically accepted, his adduction has not.[rs 4] Sufism's Chella, which is a 40-day period of retreat and fasting,[rs 11] is also unrelated to winter solstice festival.[10]

Food plays a central role in the present-day form of the celebrations. In most parts of Iran the extended family come together and enjoy a fine dinner. A wide variety of fruits and sweetmeats specifically prepared or kept for this night are served. Foods common to the celebration include watermelon, pomegranate, nuts, and dried fruit.[11] These items and more are commonly placed on a korsi, which people sit around. In some areas it is custom that forty varieties of edibles should be served during the ceremony of the night of Chelleh. Light-hearted superstitions run high on the night of Chelleh. These superstitions, however, are primarily associated with consumption. For instance, it is believed that consuming watermelons on the night of Chelleh will ensure the health and well-being of the individual during the months of summer by protecting him from falling victim to excessive heat or disease produced by hot humors. In Khorasan, there is a belief that whoever eats carrots, pears, pomegranates, and green olives will be protected against the harmful bite of insects, especially scorpions. Eating garlic on this night protects one against pains in the joints.[rs 2]

In khorasan, one of the attractive ceremony was and still is preparing Kafbikh a kind of traditional Iranian sweet is made in Khorasan, specially in the cities of Gonabad and Birjand. This is made for Yalda.[12][13]

After dinner the older individuals entertain the others by telling them tales and anecdotes. Another favorite and prevalent pastime of the night of Chelleh is fāl-e Ḥāfeẓ, which is divination using the Dīvān of Hafez (i.e. bibliomancy). It is believed that one should not divine by the Dīvān of Hafez more than three times, however, or the poet may get angry.[rs 2]

Activities common to the festival include staying up past midnight, conversation, drinking, reading poems out loud, telling stories and jokes, and, for some, dancing. Prior to the invention and prevalence of electricity, decorating and lighting the house and yard with candles was also part of the tradition, but few have continued this tradition. Another tradition is giving dried fruits and nuts and gift to family and friends specially to the bride, wrapped in tulle and tied with ribbon (similar to wedding and shower "party favors") in khorasan giving gift to the bride was obligatory.[14][15]

Gallery

[edit]-

Iranian lady recites Hafez poems on Yalda Night

-

Yaldā Night shopping in Piranshahr, Kordestan

-

2017 Yaldā Night at Sarpol-e Zahab

-

Yaldā Night cakes in Isfahan

-

Fruits and Divan of Hafez on Yaldā Night

-

During the Yalda night one of the main fruits eaten is pomegranates.

-

Various nuts, such as walnuts and pistachios, are eaten on Yalda Night.

-

The book of Ghazals of Hafez

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The first day (Ormuzd day) of Dae month was/is the first of the four name-day feast days of the Creator Ahura Mazda (Dae, "Creator"; Ormuzd = Ahura Mazda),[rs 8] for which Al-Biruni notes that in earlier times, "on the day and month both called by the name of God, i.e. (Hormuzd), [...] the king used to descend from the throne of the empire in white dresses, [...] suspend all the pomp of royalty, and exclusively give himself up to considerations of the affairs of the realm and its inhabitants." Anyone could address the king, and the monarch would meet with commoners, eat and drink with them, and he would declare his brothership with them, and acknowledge his dependency on them (Albîrûnî, "Dai-Mâh", On the Festivals in the Months of the Persians in The Chronology of Ancient Nations, tr. Sachau, pp. 211–212).

References

[edit]Group 1

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Krasnowolska, Anna (2009), "Sada Festival", Encyclopaedia Iranica, New York: iranicaonline.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g Omidsalar, Mahmoud (1990), "Čella I: In Persian Folklore", Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. V, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 123–124.

- ^ a b c Āryān, Qamar (1991), "Christianity VI: In Persian Literature.", Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. V, f5, Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, pp. 539–542.

- ^ a b c d Krasnowolska, Anna (1999), "Šab-e Čella", Folia Orientalia, 35: 55–74.

- ^ a b Dehkhoda, Ali Akbar; et al., eds. (1995), "یلدا", Loghat Nāmeh Dehkhodā: The Encyclopaedic Dictionary of the Persian Language, Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers.

- ^ Payne Smith, J., ed. (1903), "ܝܠܕܐ", Syriac Dictionary, Oxford: Clarendon, p. 192.

- ^ a b Daniel, Elton L.; Mahdi, Ali Akbar (2006), Culture and customs of Iran, Westport: Greenwood, p. 188, ISBN 0-313-32053-5.

- ^ a b Boyce, Mary (1999), "Festivals I", Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. IX, f5, Costa Mesa: Mazda, pp. 543–546.

- ^ a b Boyce, Mary (1983), "Iranian Festivals", Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 3(2), Cambridge University Press, pp. 792–818.

- ^ Razi, Hashem (1979), Gahshomari wa jashnha-e iran-e bastan, (Time-calculation and Festivals of ancient Iran), Tehran, pp. 565–631

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), repr. 2001. - ^ Algar, Hamid (1990), "Čella II: In Sufism", Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. V, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 124–125.

Group 2

[edit]- ^ "ČELLA – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org.

- ^ "UNESCO - Yaldā/Chella". ich.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-21.

- ^ "Yalda celebration | ICEC". Retrieved 2023-12-21.

- ^ "Persian Yalda night gains place on World Cultural Heritage list". Tehran Times. 2022-12-02. Retrieved 2024-12-19.

- ^ von Harnack, Adolph (1905). The Expansion of Christianity in the First Three Centuries. Williams & Norgate. p. 293.

- ^ "Yalda Night: Everything About the Longest Night of the Year". ww25.irpersiatour.com. Retrieved 2023-12-22.

- ^ de Blois, François (1996). "The Persian Calendar". Iran. 34: 39–54. doi:10.2307/4299943. ISSN 0578-6967. JSTOR 4299943.

- ^ a b Giahi Yazdi, Hamid-Reza (2020-03-01). "The Jalālī Calendar: the enigma of its radix date". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 74 (2): 165–182. doi:10.1007/s00407-019-00240-0. ISSN 1432-0657.

- ^ https://www.westminster.ac.uk/news/university-of-westminster-celebrates-yalda-night-a-night-of-light-and-togetherness

- ^ https://iranpress.com/iranians-to-celebrate-yalda-night--an-ancient-tradition-of-light-and-togetherness

- ^ Bahrami, Askar, Jashnha-ye Iranian, Tehran, 1383, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Dr.Mohammad Ajam. KafBikh. Parssea.

- ^ Foods in iran. ISNA. 2011.

- ^ Dr.Mohammad Ajam. yalda traditions. parssea 2011.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20201113021446/http://parssea.org/?p=5214 . (2011). Foods in iran. parssea.

{{cite book}}: External link in|author=

External links

[edit] Media related to Yalda Night at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Yalda Night at Wikimedia Commons- "Čella" at Encyclopædia Iranica

- Article about Yalda night on Irpersiatour website