Wycliffe Hall, Oxford

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Wycliffe Hall | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Oxford | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Arms: Gules, an open book proper the pages inscribed with the Latin words "Via Veritas Vita" in letters sable on a chief azure three crosses crosslet argent and in base an estoile or. | |||||||||||||

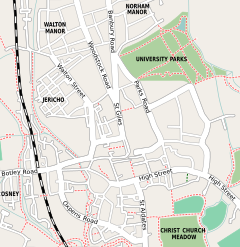

| Location | 54 Banbury Road, Oxford | ||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 51°45′47″N 1°15′36″W / 51.76302°N 1.260095°W | ||||||||||||

| Latin name | Aula Wiclefi | ||||||||||||

| Motto | Via, Veritas, Vita "The Way, the Truth, the Life" (John 14:6) | ||||||||||||

| Established | 1877 | ||||||||||||

| Named for | John Wycliffe | ||||||||||||

| Sister college | Ridley Hall, Cambridge | ||||||||||||

| Principal | Michael Lloyd | ||||||||||||

| Undergraduates | ~90 | ||||||||||||

| Postgraduates | ~30 | ||||||||||||

| Visiting students | ~50 | ||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||||

Wycliffe Hall (/ˈwɪklɪf/) is a permanent private hall of the University of Oxford affiliated with the Church of England, specialising in philosophy, theology, and religion. It is named after the Bible translator and reformer John Wycliffe, who was master of Balliol College, Oxford in the 14th century.

Founded in 1877, Wycliffe Hall provides theological training to women and men for ordained and lay ministries in the Church of England as well as other Anglican and non-Anglican churches. There are also a number of independent students studying theology, education and philosophy at undergraduate or postgraduate level. The hall is rooted in and has a history of Evangelical Anglicanism and includes strong influences of Charismatic, Conservative and Open Evangelical traditions.

The hall is the third-oldest Anglican theological college and, as of April 2020, claimed to have trained more serving Church of England bishops than any other such institution (21 of c. 116).[1]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]For many centuries membership of the University of Oxford required subscription to the 39 Articles (part of the English Reformation heritage of the Church of England). The university was officially secularised by the Oxford University Act 1854 and the Universities Tests Act 1871, when it was opened respectively to students and lecturers of all religious creeds or none. Evangelical public meetings were held in 1876, partly in response to this development, where concerns were raised about how "the majority of clergy are professionally ignorant".[2] A committee, including Charles Perry and Sydney Gedge MP, was formed to raise funds for two new theological colleges, one at Cambridge and one at Oxford, which would provide supplementary training preparatory to ordination and do so "upon a sound Evangelical and Protestant basis".[3]

Funds were gathered rapidly and a founding council was formed for the Oxford college, including J. C. Ryle, Robert Payne Smith, Edward Garbett, and Edmund Knox. The vision was to maintain the teaching of biblical and evangelical theology at Oxford and to promote "doctrinal truth and vital godliness", training ordinands to be "mighty in scripture...prepared to maintain the pure doctrines of the Reformed Church of England in all their simplicity and fullness".[4] The new hall was dedicated to John Wycliffe, who was master of Balliol College, Oxford in the 1360s, and is remembered as the 'morning star' of the Reformation.

Wycliffe is one of more than 20 Anglican theological colleges established in England during the late 19th century – including its "sister college" is Ridley Hall, Cambridge, which opened in 1881. Two evangelical organisations working among Oxford students were founded in the late nineteenth century; the Oxford Inter-Collegiate Christian Union in 1879 and the Oxford Pastorate in 1893. Wycliffe had close links with both from their inception. Indeed, of Wycliffe's first 100 students, 83 were Oxford graduates; a link that was bolstered by the second principal, Chavasse, who was incumbent of St Peter-le-Bailey, Oxford prior to leading the hall. The hall opened to non-graduates in 1890.[citation needed]

Twentieth century

[edit]

William Henry Griffith Thomas was one of Wycliffe Hall's best known principals (serving 1905–1910) and remains a noted theologian. He undertook much of the lecturing in college himself during his tenure[5] and is remembered today by a bronze bust in the dining room.[citation needed]

During the First World War, Wycliffe Hall housed refugees from Serbia and trainees from the Royal Flying Corps who built a practice aeroplane in the dining hall.[6] At the jubilee of the hall in 1927, the principal led students to Jerusalem for their summer vacation term. Wycliffe Hall staff and students conducted four further pilgrimages to Jerusalem, in 1929, 1931, 1934 and 1937, mostly without incident, though during the 1929 trip students were commissioned as peacekeepers during riots and one student was shot through the shoulder.[7] Two further years later, the principal who led these expeditions (F. G. Brown) was elected Protestant Bishop in Jerusalem. Photos from these 1920s expeditions decorate the walls of No. 4 Norham Gardens today. The chapel organ was rebuilt in 1936 and rededicated by the Bishop of Leicester.[8]

Religious liberalism influenced Wycliffe Hall in the 1950s and '60s. F. J. Taylor (principal 1956–1962) was editor of the liberal-Catholic Parish and People magazine, whilst David Anderson (principal 1962–1969) was a contributor to the Modern Churchmen's Union. The evangelical churches lost confidence in the hall and student numbers fell dramatically.[9] An official 1965 report on the hall warned that 'dialogue with the present age...must be founded on and spring from evangelical conviction'.[10] Eventually, the Hall Council asked for Anderson's resignation in 1969 and instead sought clearer evangelical leadership, even inviting John Stott to take up the post.[11] Stott declined, but other well-known evangelicals were found to get the hall back onto a firmer footing, including Peter Southwell, David Holloway, Oliver O'Donovan, and Roger Beckwith.[citation needed]

The centenary of the hall was celebrated in 1977 with a service of thanksgiving at Christ Church, Oxford, followed by tea in a marquee on the Wycliffe lawn. In 1996 Wycliffe Hall became a permanent private hall of the University of Oxford, under the leadership of Alister McGrath.[citation needed]

Recent developments

[edit]Two significant new programmes were launched in the early years of the new century; SCIO (Scholarship and Christianity in Oxford) in 2002; and OCCA (the Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics) in 2005. SCIO is run in partnership with the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU) whilst OCCA is operated by the RZIM Zacharias Trust. Both programmes brought dozens of students to the hall each year, which SCIO continues to do, though the hall's relationship with OCCA was discontinued in 2019.[citation needed]

Wycliffe became a focus of media attention in 2007 when a significant number of the academic staff left, including the vice-principal and head of pastoral theology. Three former principals wrote to the chair of the Hall Council to protest about the way staff complaints of being bullied were ignored.[12] The crisis continued as a member of the council also resigned, having no confidence in the Chair of Council, Bishop James Jones.[13] The issues became public as members of the academic faculty lodged grievances against the principal, Richard Turnbull, for bullying.[14] After monitoring by the university, senior academics at Oxford complained that the curriculum was narrow and offered students insufficient intellectual development.[15] That year the bishop and the hall were taken to an employment tribunal and admitted breaking the law. In 2009 the hall was inspected by the Bishops' Inspection: it was commended in some departments but the inspectors expressed "no confidence" in its practical and pastoral theology.[16][17] Shortly after, the bishop, James Jones, resigned as chair. In May 2012, under a new chair, the Bishop of Chester, the principal was given leave of absence and he stepped down the following month. Late in 2012 the hall began advertising for a new principal who could offer "wide and generous understanding of the major trends in contemporary Anglican evangelicalism, together with high level pastoral skills". In December 2012 it was announced that Mike Hill, Bishop of Bristol, had become chair of the Hall Council.[18] The process of appointment of a new principal stalled in January 2013: the Hall Council considered that five candidates were "of real quality" but that none of them offered "the desired balance of skills and attributes" required.[19]

In April 2013 the hall announced that Michael Lloyd, Chaplain of Queen's College, Oxford, had been appointed as principal,[20] and he took up the position in the middle of the year and has been creatively expanding the hall and looking to increase the numbers of female ordinands.[21]

The small cohorts of first degree undergraduates which Wycliffe accepted from 1997 onwards were phased out in the mid-2010s and, aside from SCIO, the hall now only takes mature students (over 21s).

Buildings

[edit]Throughout its existence, Wycliffe has been located in the Victorian suburb of North Oxford. A site in the centre of Oxford was sought at the hall's foundation, and again in the 1890s, but neither attempt succeeded.[22] The original buildings on the Wycliffe Hall site were designed in the 1860s as family houses, until converted to their present use later in the nineteenth century.[citation needed]

The hall - No. 54 Banbury Road was designed by John Gibbs in 1866 and built for Tom Arnold the younger, literary scholar and son of Tom Arnold the elder, head of Rugby School. The house, named "Laleham", after the Arnolds' former residence in Middlesex, was larger than normal, even in a neighbourhood known for substantial houses. This size was to accommodate Arnold's anticipated in-house tutees. Within a decade, Arnold decided to sell No. 54 as the tutorial business was abandoned. A committee of evangelical churchmen bought the property in 1877 and promptly renamed it Wycliffe Hall. In the early years, the northerly main room was the library-cum-lecture room, while the southerly one was the dining room. Additions were soon made to the house by William Wilkinson and Harry Wilkinson Moore in 1882–1883. The new North Wing contained a dozen additional student rooms, while South Wing, housed the hall's purpose-built library as well as a new front entrance, thus allowing the dining room to be extended into the hall of No. 54. A new purpose-built dining hall was built on the road-side (i.e. west) of No. 54 Banbury Road in 1913, blocking off both of the original main entrances to the hall (the 1866 and 1883 doors), but providing a new front door featuring the hall and university shields in the stonework doorframe, still visible today. South Wing was converted for use as an additional common room (the LCR) in 1974, while the dining hall was converted for use as a lecture theatre in 1980.[citation needed]

Old Lodge - No. 52 Banbury Road lies immediately south of No. 54, at the junction with Norham Gardens, and was designed by Frederick Codd in 1868.[23][24] It initially housed the Holy Rood Convent (an Anglo-Catholic nunnery of the Society of the Most Holy Trinity, which was involved in printing the works of John Henry Newman). The hall acquired No. 52 when the sisters sold up in 1883. This second villa initially functioned as the principal's residence, but in 1930 was converted to contain both student and staff common rooms on the ground floor – hence 'Old' Lodge. In 1974 the hall's library was moved from South Wing into Old Lodge, where it remains to this day.[citation needed]

A chapel and bellcote was added between No. 54 and No. 52 in 1896, designed by architect George Wallace.[24] The chapel was opened by the Bishop of Oxford and has a stained-glass window depicting John Wycliffe. A vestry was added to the south side of the chapel in the 1930s, which is now being used as a prayer room. A 1961 reordering of the east end saw the introduction of candlesticks and altar frontals, which were removed in a later reordering. The 1960s metal reredos cross is now hung in the corridor between the main part of the hall and Old Lodge.[citation needed]

During the twentieth century, a number of houses in Norham Gardens were also acquired by the hall, including No. 2 in 1930 (which date also saw the acquisition of the freeholds from St John's College). The gardens of No. 2 and No. 4 remained separately delineated by their original brick party walls for some decades, but these grounds were amalgamated with the garden of 54 Banbury Road to form a large green space on the site in the late 1960s. No. 2 Norham Gardens was used as a replacement lodging for the hall's principal through much of the century, but saw use by TocH during the Second World War.[citation needed]

Various schemes were considered in the late 1960s and early 1970s for merging Wycliffe with other institutions, including Mansfield College, Oxford, St Stephen's House, Oxford, and Ripon Hall. Options under serious consideration by the Hall Council included the demolition of one or more of the four original villas; operating a split-site college with St Stephen's; and selling the original buildings to rebuild on part of Mansfield's site or elsewhere in or out of the city. None of these schemes came to pass.[citation needed]

The Talbot Rice Dining Hall was built to the east of No. 54 Banbury Road and opened in October 1980, allowing the 1913 dining hall to become a lecture theatre. At the same time St Stephen's House moved to Iffley Road and the Hall Council considered buying No. 17–19 Norham Gardens, but ultimately was out-bid by St Edmund Hall, Oxford. Later in the same decade No. 2a Norham Gardens was built as a new lodging for the principal. The last major building work on the main site was the western extension of No. 2 Norham Gardens in the mid-1990s to provide additional accommodation and offices. No. 8 Norham Gardens was acquired in the early 2000s.[citation needed]

Ministerial formation

[edit]

Ordination training remains central to the work of the hall, whose original purpose was to train men for ordained ministry in both the home and colonial service of the Church of England. Non-ordained ministries are also catered for, especially through courses in academic theology and apologetics.[citation needed]

Attendance at the daily chapel services is compulsory for full-time ordinands and optional for independent students.[25] For much of the hall's history, Greek was a daily ritual for all students; and training in the biblical languages remains important today, with all ministerial students strongly encouraged to take either or both of Greek and Hebrew.[citation needed] Practical ministerial training is delivered via a system of Integrated Study Weeks on topics such as death, evangelism, ethics, and biblical hermeneutics.[26] Student led fellowship groups supervised by college tutors, which take turns to run a week of chapel services, and training and practice in preaching are key elements of ministerial formation.[27]

Historically, Wycliffe students were assigned a 'pastoral job' on Sundays – whether preaching, pastoral visiting, or taking a Sunday school class.[28] Today, ministry placements in churches and colleges emphasise observation and theological reflection as well as participation,[29] and a longer summer placement, before a student's final year, affords the opportunity to go further afield.[citation needed] Ministerial students also participate in college missions during their studies, with the choice of settings including schools, universities, urban and rural parishes, as well as social projects of various kinds.[citation needed]

Academic programmes and achievements

[edit]

Wycliffe Hall students are enrolled on a wide range of Oxford academic programmes, including the Certificate in Theological Studies, Diploma in Theological Studies, Bachelor of Arts in Theology, Bachelor of Theology, Master of Theology, Master of Philosophy in Theology, and doctoral programmes.

In 2012, the hall topped the University of Oxford's Norrington Table, winning each of the theology prizes and with all five BA students achieving a first class degree.[30] The hall topped the Norrington Table again in 2017.[31]

Student life

[edit]

The modern student body includes about 60 Church of England ordinands and about 60 independent students, plus up to 50 visiting students (mostly on the SCIO programme). Many nationalities are represented, with the largest single body of overseas students being from the United States. The Buechner prize for creative writing, named in honour of the acclaimed American author Frederick Buechner, is awarded annually.[32] Students may also take part in activities across the wider university, including sports.[citation needed] For full-time students there is some student accommodation on-site, and students may take eat in the dining hall on weekdays. There are three or four formal dinners per term. All ministerial students are expected to take on at least one 'college duty'.[citation needed] Activities for spouses of students include a mid-week prayer, Bible study and fellowship meeting.[33]

People associated with the college

[edit]Hall Council chairmen

[edit]Partial list

- 1877 Robert Payne Smith, Dean of Canterbury[34]

- 1948 Christopher Chavasse, Bishop of Rochester

- 1969 Stuart Blanch, Bishop of Liverpool[35]

- 2005 James Jones, Bishop of Liverpool

- 2009 Peter Forster, Bishop of Chester

- 2012 Mike Hill, Bishop of Bristol

- 2016 Julian Henderson, Bishop of Blackburn

Principals

[edit]- Robert Baker Girdlestone, 1877–1889 (Victorian Biblical scholar)

- Francis James Chavasse, 1889–1900 (subsequently second Bishop of Liverpool 1900–1923)

- Harry George Grey, 1900–1905 (subsequently returned to service as a missionary in the Punjab)

- William Griffith Thomas, 1905–1910 (Wycliffe's computer room is named after him)

- Harry George Grey, 1910–1918 (retired)

- Henry "Harry" Beaujon Gooding, 1919–1925 (subsequently returned to Barbados as Headmaster of The Lodge School 1932–1941)[36]

- Francis Graham Brown, 1925–1932 (subsequently sixth Anglican Bishop of Jerusalem 1932–1942)

- John Taylor, 1932 to 1942 (subsequently Bishop of Sodor and Man 1942–1954)

- Julian Thornton-Duesbery, 1943 to 1955[37] (previously and subsequently Master of St Peter's College, Oxford 1940–1968)

- Francis John Taylor, 1956–1962 (subsequently third Bishop of Sheffield 1962–1971)

- David Anderson, 1962–1970 (resigned due to falling student numbers)[38]

- James (Jim) Peter Hickinbotham, 1970–1978 (retired)[39]

- Geoffrey Shaw, 1978–1988[40] (retired)

- R. T. France, 1989–1995[41] (subsequently Rector of Wentnor)[42]

- Alister McGrath, 1995–2005 (subsequently Director, Ian Ramsey Centre for Science and Religion)[43]

- Richard Turnbull, 2005–2012 (subsequently Director, Centre for Enterprise Markets and Ethics)[44]

- Michael Lloyd, 2013 to present

A gallery of former principals decorates the staircase of South Wing.

Notable alumni

[edit]1877–1900

[edit]- William Henry Temple Gairdner (1896–97) – Missionary in Cairo and amongst Muslims, apologist

1900–1945

[edit]- Hewlett Johnson (1900–1901) – The "Red Dean" of Canterbury

- Lamina Sankoh (1921–1924)

- Leonard Wilson (1922–1923) – 4th Bishop of Birmingham

- Verrier Elwin (1925–1926) – President of the OICCU who later converted to Hinduism

- Joseph Fison (1929–1930) – 74th Bishop of Salisbury

- Wilbert Awdry (1932–1933) – Creator of The Railway Series of children's books

- Donald Coggan (1934) – 101st Archbishop of Canterbury

- John Vernon Taylor (1937–1938) – 94th Bishop of Winchester

- Gordon Strutt (1942–1943) – 3rd Bishop of Stockport

- William Chadwick – 4th Bishop of Barking

- Howard Cruse – 5th Bishop of Knaresborough

1945–1970

[edit]- Stuart Blanch (1946–1948) – 5th Bishop of Liverpool, 94th Archbishop of York

- Alec Motyer (1947) – Leading Old Testament scholar & 1st Principal of Trinity College, Bristol

- J. I. Packer (1949–1952) – Author (inc. General Editor of the English Standard Version) and theologian

- Henry Moore (1950–1952) – 2nd Bishop in Cyprus and the Gulf

- Joseph Abiodun Adetiloye (1951–1953) – Bishop of Lagos and 2nd Primate of All Nigeria

- David Young (1958–1959) – 11th Bishop of Ripon

- Ian Harland (1958–1960) – 65th Bishop of Carlisle

- Oliver O'Donovan (1968–1972) – Leading ethicist & Regius Professorship of Moral and Pastoral Theology emeritus

- Bill Sykes – Chaplain of University College, Oxford and author

1970s

[edit]- Colin Fletcher (1972–1975) – 7th Bishop of Dorchester

- N.T. Wright (1973–1975) – Writer and theologian, 94th Bishop of Durham

- James Harold Bell (1974–1975) – 10th Bishop of Knaresborough

- Nick McKinnel (1977–1980) – 10th Bishop of Plymouth

- June Osborne (1978–1980) – 72nd Bishop of Llandaff

- Alan Gregory Clayton Smith (1979–1981) – 10th Bishop of St Alban's

1980s

[edit]- Paul Butler (1980-1983) – 96th Bishop of Durham

- James Stuart Jones (1981–1982) – 7th Bishop of Liverpool

- Peter Hill (1981–1983) – 11th Bishop of Barking

- David Urquhart (1982–1984) – 9th Bishop of Birmingham

- Carl N. Cooper (1982–1985) – 127th Bishop of St David's

- John Thomson (1982–1985) – 8th Bishop of Selby

- Nicky Gumbel (1983–1986) – Vicar of Holy Trinity Brompton and developer of the Alpha Course

- Graham Tomlin (1983–1986) – 12th Bishop of Kensington and President of St Mellitus College

- Anne Dyer (1984–1987) – 12th Bishop of Aberdeen and Orkney and former Warden of Cranmer Hall, Durham

- Anthony Burton (1985–1987) – 11th Bishop of Saskatchewan

- Philip Mounstephen (1985–1988) – 16th Bishop of Truro

- Jonathan Goodall (1986–1989) – 5th Bishop of Ebbsfleet

- David Williams (1986–1989) – 6th Bishop of Basingstoke

- Toby Howarth (1987–1990) – 11th Bishop of Bradford

- Vaughan Roberts (1989–1991) – Rector of St Ebbe's Church, Oxford and President of the Proclamation Trust

- Ray R. Sutton – Bishop in the Reformed Episcopal Church

1990s

[edit]- Michael Horton (early 1990s) – Theologian, J.Gresham Machen Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics, Westminster Seminary

- Paul Gavin Williams (1990–1992) – Member of the House of Lords, 13th Bishop of Southwell and Nottingham

- Rod Thomas (1991–1993) – 9th Bishop of Maidstone

- Rico Tice (1991–1994) – Evangelist, co-writer of the Christianity Explored course

- Rachel Treweek (1991–1994) – Member of the House of Lords, 41st Bishop of Gloucester

- Martyn Snow (1992-1995) – Member of the House of Lords, 7th Bishop of Leicester

- Ric Thorpe (1993–1996) – 2nd Bishop of Islington

- Nicholas Dill (1996-1999) – 12th Bishop of Bermuda

- Vicky Beeching (1997–2000) – Worship Leader and LGBT advocate

- Jonathan Aitken – Politician, author and broadcaster

2000s

[edit]- D. Michael Lindsay (2000–2001) – President of Taylor University, former President of Gordon College, Massachusetts

- Jill Duff (2000–2003) – 8th Bishop of Lancaster

Fellows

[edit]- Clair Linzey – animal rights advocate

References

[edit]- ^ "Record Number of Serving Wycliffe-trained Bishops". www.wycliffe.ox.ac.uk.

- ^ Nicholas Groves (2004). Theological Colleges: their hoods and histories. The Burgon Society. p. 35. ISBN 0954411013.

- ^ "The Guardian, 27 June 1877". p. 894.

- ^ Theological Halls at Oxford and Cambridge. Bodleian Library. p. 536.

- ^ "Church Society - Issues - History - Griffith Thomas - Portman/Wycliffe Hall". churchsociety.org. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ Christopher Hibbert (ed.), The Encyclopaedia of Oxford (London: Macmillan, 1988), p.507

- ^ Andrew Atherstone, 'Evangelical Pilgrims to the Holy Land: Wycliffe Hall's Encounter with the Eastern Churches 1927-1937', Sobornost 30:2 (2008), pp.37-58

- ^ 'Miscellaneous', Musical Times 77/1116 (February 1936), p.153

- ^ Andrew Atherstone, Rescued from the Brink: The Collapse and Resurgence of Wycliffe Hall, Oxford in Studies in Church History Volume 44, 2008, p.355–365

- ^ Central Advisory Committee on Training for the Ministry Inspection Report 1965

- ^ Timothy Dudley-Smith, John Stott (biography) (2 vols, Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 2001), II pp.72-75

- ^ Stephen Bates, Theological College's Head is undermining it, says Predecessors, The Guardian, 14 June 2007

- ^ Crisis continues at Wycliffe Hall as Council member resigns. The controversy over Oxford theological college Wycliffe Hall has taken another dramatic turn after a council member resigned this week, saying she had serious concerns over the response of the hall to allegations of bullying and intimidation. Daniel Blake, 5 October 2007, Christian Today

- ^ Eeva John., Geoff Maughan and David letters, Wenham, #Church of England Newspaper# 28 September 2007

- ^ Stephen Bates, religious affairs correspondent (11 August 2007). ""gives warning to theological college", The Guardian, 11 August 2007". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Dave Walker, www.churchtimes.co.uk/blog_post.asp?id

- ^ Pat Ashworth, Church Times, 20 March 2009.

- ^ "Appointment of Chair of Council". Wycliffe Hall. 7 December 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ "Statement from the Hall council on the appointment of the Principal of Wycliffe Hall". Archived from the original on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ "Appoints New Principal". Wycliffe Hall. 15 April 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ "Female Ordinand Mentoring". Wycliffe Hall. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ Smith, Eric (1978). St Peter's; The Founding of an Oxford College. Gerrard's Cross: Colin Smythe. p. 18. ISBN 0-901072-99-0.

- ^ Hinchcliffe, Tanis (1992). North Oxford. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. pp. 143–144, 151–153, 217. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.

- ^ a b Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). The Buildings of England: Oxfordshire. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 319. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.

- ^ Wycliffe Ministry & Formation Handbook (2017-18), p.11

- ^ Wycliffe Ministry & Formation Handbook (2017-18), p.19ff

- ^ Wycliffe Ministry & Formation Handbook (2017-18), p.21ff

- ^ R.B. Girdlestone, 'Words to Workers' (London: Hamilton, Adams & Co, 1885), preface

- ^ Wycliffe Ministry & Formation Handbook (2017-18), p.44ff

- ^ "Achieves Top Marks". Wycliffe Hall. 7 December 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ '2017 Achievements', The Wycliffite magazine (May 2018), p.3

- ^ "Buechner Prize Awarded". Wycliffe Hall, Oxford.

- ^ Wycliffe Student Handbook (2018/19), p.19

- ^ 'Theological Halls at Oxford and Cambridge' (endowment fund appeal), Miscellaneous Papers relating to Wycliffe Hall, G.A. Oxon 4A 536 (Bodleian Library, Oxford)

- ^ Timothy Dudley-Smith, John Stott (biography) (2 vols, Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 2001), II p.73

- ^ Hoyos, F. A. (8 November 1952). "Our Common Heritage - (29) Harry Gooding" (PDF). Barbados Advocate. pp. 4, 8. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ "The Rev Canon J. P. Thornton-Duesbery". The Times. No. 62106. 8 April 1985. p. 12.

- ^ Andrew Atherstone, Rescued from the Brink: The Collapse and Resurgence of Wycliffe Hall, Oxford in Studies in Church History Volume 44, 2008, p.366

- ^ "Theological Colleges and Training". Lambeth Palace Library. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

GB/109/16953 Hickinbotham; James Peter (1914-1990); Principal, Wycliffe Hall

- ^ Whyte, Duncan (23 March 2011). "Obituary: Canon Geoffrey Norman Shaw". Church Times. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ "Obituary: Canon Dick France". Daily Telegraph. 17 April 2012.

- ^ "Canon Dick France". 17 April 2012 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "Professor Alister McGrath - Faculty of Theology and Religion". www.theology.ox.ac.uk.

- ^ "Our Team".

External links

[edit]- Wycliffe Hall, Oxford

- School buildings completed in 1866

- School buildings completed in 1868

- Educational institutions established in 1877

- Permanent private halls of the University of Oxford

- Bible colleges, seminaries and theological colleges in England

- Anglican seminaries and theological colleges

- Evangelicalism in the Church of England

- Buildings and structures of the University of Oxford

- 1877 establishments in England