Window shopping

Window shopping, sometimes called browsing, refers to an activity in which a consumer browses through or examines a store's merchandise as a form of leisure or external search behaviour without a current intent to buy. Depending on the individual, window shopping can be a pastime or be used to obtain information about a product's development, brand differences, or sale prices.[1]

The development of window shopping, as a form of recreation, is strongly associated with the rise of the middle classes in 17th and 18th century Europe. Glazing was a central feature of the grand shopping arcades that spread across Europe, from the late 18th century. Promenading in these arcades became a popular 19th-century pastime for the emerging middle classes.

Traditionally, window shopping involves visiting a brick-and-mortar store to examine the goods on display, but it is also done online in recent times due to the availability of the internet and e-commerce. A person who engages in window shopping is known as a window shopper.

History

[edit]

The development of window shopping, as a form of recreation, is strongly associated with the rise of the middle classes in 17th- and 18th-century Europe.[2] As standards of living improved in the 17th century, consumers from a broad range of social backgrounds began to purchase goods that were in excess of basic necessities. An emergent middle class or bourgeoisie stimulated demand for luxury goods, and the act of shopping came to be seen as a pleasurable pastime or form of entertainment.[3] Shopping for pleasure became a particularly important activity for middle and upper-class women, since it allowed them to enter the public sphere without the need for a chaperone.[4]

Prior to the 17th century, glazed shop windows were virtually unknown. Instead, early shopkeepers typically had a front door with two wider openings on either side, each covered with shutters. The shutters were designed to open so that the top portion formed a canopy while the bottom was fitted with legs so that it could serve as a shopboard.[5] Scholars have suggested that the medieval shopper's experience was very different. Many stores had openings onto the street from which they served customers. Glazed windows, which were rare in medieval times, meant that shop interiors were dark places which militated against detailed examination of the merchandise. Shoppers, who rarely entered the shop, had relatively few opportunities to inspect the merchandise prior to purchase.[6]

Glazing was widely used from the early 18th century. English commentators pointed to the speed at which glazing was installed. Daniel Defoe, writing in 1726, noted, "Never was there such painting and guildings, such sashings and looking-glasses as the shopkeepers as there is now."[7] The widespread availability of plate glass in the 18th century led shop owners to build windows that spanned the full lengths of their shops for the display of merchandise to draw in customers. One of the first Londoners to experiment with this new glazing in a retail context was the tailor Francis Place at his Charing Cross establishment.[8]

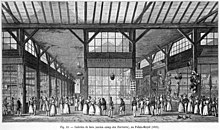

In Paris, where pedestrian pavements were few, retailers were eager to attract window shoppers by providing a safe shopping environment away from the filthy and noisy streets, and began to construct rudimentary arcades, which eventually evolved into the grand arcades of the late 18th century and which dominated retail throughout the 19th century.[9] Opening in 1771, the Colisée, situated on the Champs Elysées, consisted of three arcades, each with ten shops, all running off a central ballroom. Parisians saw this location as too remote, and the arcade closed within two years of opening.[5] However, the Galerie de Bois, a series of wooden shops linked to the ends of the Palais-Royal (pictured), opened in 1786 and became a central part of Parisian social life.[10] Within a decade, the Palais shopping complex added many more shops, as well as cafés and theatres.[11] In its heyday, the Palais-Royal was a complex of gardens, shops and entertainment venues situated on the external perimeter of the old palace grounds, under the original colonnades. The area boasted some 145 boutiques, cafés, salons, hair salons, bookshops, museums, and numerous refreshment kiosks, as well as two theatres. The retail outlets specialised in luxury goods such as fine jewellery, furs, paintings and furniture designed to appeal to the wealthy elite.[11]

Inspired by the success of the Palais-Royal, retailers across Europe erected grand shopping arcades and largely followed the Parisian model which included extensive use of pane glass. Not only were the shopfronts made of pane glass, but a characteristic feature of the modern shopping arcade was the use of glass in an atrium-styled roofline, which allowed for natural light and reduced the need for candles or electric lighting.[5] Modern grand arcades opened across Europe and in the Antipodes.[9] The Passage de Feydeau in Paris (opened in 1791) and Passage du Claire in 1799;[5] London's Piccadilly Arcade (opened in 1810); Paris's Passage Colbert (1826) and Milan's Galleria Vittorio Emanuele (1878).[12] London's Burlington Arcade, which opened in 1819, positioned itself as an elegant and exclusive venue designed to attract the elite, from the outset.[13] Some of the earliest examples of shopping arcades with expansive glazed shop-windows appeared in Paris. These were among the first modern shops to make use of glazed windows to display merchandise. Other notable nineteenth-century grand arcades included the Galeries Royales Saint-Hubert in Brussels which was inaugurated in 1847, Istanbul's Çiçek Pasajı opened in 1870 and Milan's Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, first opened in 1877.

Promenading in these arcades became a popular nineteenth-century pastime for the emerging middle classes. Designed to attract the genteel middle class, these shopping arcades came to be the place to shop and to be seen.[13] Individual stores fitted with long glass exterior windows allowed the emerging middle classes to window shop and indulge in fantasies, even when they may not have been able to afford the high retail prices of the luxury outlets inside the arcade.[14]

By the 1900s the popularity of window displays had heightened and the window display became more elaborate, continuing to attract not only those that wanted to make purchases but also passers-by that appreciated beauty. To achieve the right aesthetics, store owners and managers would hire decorators or window dressers to attractively arrange merchandise in the shop windows; indeed, the professional window display design soon became an object used to lure shoppers into the stores.[15]

As a form of leisure

[edit]Most men mistakenly assume that you look into show windows to find something to buy. Women know better. They enjoy window-shopping for its own sake. Store windows, when you look into them with pleasure-seeking eyes, are strange places full of mental adventure. They contain first clues to dozens of treasure hunts which if you follow them, lead to as many different varieties of treasure. – MW Marston, The Rotarian, September 1938[16]

Window shopping was synonymous with being in the city and moreover offered women a legitimate reason to be able to move around in public without a chaperone.[15] In the late 1800s it was a minor scandal to move around in public without a male chaperone because not everyone was happy about the intrusion of women into urban life. Many looked down on females who walked the streets alone and even newspaper columnists condemned their shopping habits as "salacious acts of public consumerism."[2] However, the rise of window displays soon gave women a foothold in the modern city, and for many, a new pastime. Soon, housewives started roaming the city under the pretext of shopping. "Shopping" in this context did not always involve an actual purchase, it was more about the pleasures of perusing, taking in the sights, the displays, and the people.[2]

Prior to the introduction of plate glass for shops and the development of window shopping, people could not just enter shops without the intention to make a purchase; even less so to walk around just for fun or to pass time. Most stores before and during World War II were small, with not enough space for people to just go and linger about. The early department stores pioneered the transformation of traditional customers into modern consumers and of mere "merchandise" into spectacular "commodity signs" or "symbolic goods". Thus they laid the cornerstones of a culture we still inhabit.[17] Peoples' patronage of stores transformed from just walking in, buying and leaving to "shopping", especially for females. Shopping no longer consisted of haggling with the seller but of the ability to dream with one's eyes open, to gaze at commodities and enjoy their sensory spectacle.[18]

With the development of large out-of-town malls, especially after WWII, and more recently sales outlets in central high streets, shopping places are becoming hybrid spaces mixing goods and leisure in varied proportions.[19] Traditional small forms of stores and retail distributors have been replaced with large malls and shopping centres which now characterize contemporary Western retail. In these modern times, though malls and shopping centres have fixed prices, one can enter and leave as one wants without purchasing any item. It has become a place of socialization or leisure for most people, especially women.

Indeed, the pleasures, meanings and competences which consumers put to work in shopping centres and department stores are far broader than their ability to bargain on price and purchase objects: in these spaces people do not just buy things, they keep up with the world of things, spending time with friends in a polished environment filled with both fantasy and information. In fact, around a third of those who enter a shopping centre leave without having bought anything.[20][21]

In practice, thus, window shopping is an assorted activity, done differently according to the shopper's social identity.

Online window shopping

[edit]There are some types of consumers who spend a lot of time in online marketplaces but never purchase anything or even have the intention to buy and since there are no "transportation costs" required on visiting an online store site, it is much easier than visiting a brick-and-mortar store.[22] This cluster of online consumers are called "e-window shoppers", as they are predominantly driven by stimulation and are only motivated to surf the internet by visiting interesting shopping websites. These e-shoppers appear as curious shoppers that are only interested in seeing what is out there rather than trying to negotiate to obtain the lowest possible price.[23] These online window shoppers use news and pictures of products to seek hedonic experiences as well as keep themselves up to date with the industry status and new trends.[22] Similarly, since 2006, unboxing videos began to explode in popularity, offering a new form of window shopping.[24][25]

Popular culture

[edit]Music

[edit]- "Window Shopper", a single by rapper 50 Cent

- "Window Shopping", a song written by Marcel Joseph and popularized by country singer Hank Williams, who released the song in July 1952 on MGM Records

- "Nan, you’re a Window Shopper", a parody of 50 Cent's Window Shopper by Lily Allen

- "Window Shopping", a stock song on Capital Records' Media Music albums

Film

[edit]- Breakfast at Tiffany's, a 1961 American romantic comedy film directed by Blake Edwards and written by George Axelrod, featured Audrey Hepburn window shopping at Tiffany & Co. in the first scene.

Books

[edit]- Fashion Window Shopping, a book by David Choi

- Window Shopping, a book by Anne Friedberg

- Window-shopping through the iron curtain, a book by David Hlynsky

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bloch, P.; Richins, M. (1983). "Shopping without purchase: An investigation of consumer browsing behaviour". In Bagozzi, R; Tybout, A (eds.). Advances in consumer. Vol. 11. Provo, UT: Association for consumer research. pp. 389–393.

- ^ a b c "The secret feminist history of shopping". 1 January 2017.

- ^ Jones, C. and Spang, R., "Sans Culottes, Sans Café, Sans Tabac: Shifting Realms of Luxury and Necessity in Eighteenth-Century France," Chapter 2 in Consumers and Luxury: Consumer Culture in Europe, 1650–1850 Berg, M. and Clifford, H., Manchester University Press, 1999; Berg, M., "New Commodities, Luxuries and Their Consumers in Nineteenth-Century England," Chapter 3 in Consumers and Luxury: Consumer Culture in Europe, 1650–1850 Berg, M. and Clifford, H., Manchester University Press, 1999

- ^ Rappaport, E.F., Shopping for Pleasure: Women in the Making of London's West End, Princeton University Press, 2001, especially see Chapter 2

- ^ a b c d Conlin, J., Tales of Two Cities: Paris, London and the Birth of the Modern City, Atlantic Books, 2013, Chapter 2

- ^ Cox, N.C. and Dannehl, K., Perceptions of Retailing in Early Modern England, Aldershot, Hampshire, Ashgate, 2007, p. 155

- ^ Cited in Conlin, J., Tales of Two Cities: Paris, London and the Birth of the Modern City, Atlantic Books, 2013, Chapter 2

- ^ Robertson, Patrick (2011). Robertson's Book of Firsts: Who Did What for the First Time. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- ^ a b Lemoine, B., Les Passages Couverts, Paris: Délégation à l'action artistique de la ville de Paris [AAVP], 1990. ISBN 9782905118219.

- ^ Conlin, J., Tales of Two Cities: Paris, London and the Birth of the Modern City, Atlantic Books, 2013, Chapter 2; Willsher, K., "Paris's Galeries de Bois, Prototype of the Modern Shopping Centre," [A history of cities in 50 buildings, day 6], 30 March 2015

- ^ a b Byrne-Paquet, L., The Urge to Splurge: A Social History of Shopping, ECW Press, Toronto, Canada, pp. 90–93

- ^ Sassatelli, R., Consumer Culture: History, Theory and Politics, Sage, 2007, p. 27

- ^ a b Byrne-Paquet, L., The Urge to Splurge: A Social History of Shopping, ECW Press, Toronto, Canada, pp. 92–95

- ^ Byrne-Paquet, L., The Urge to Splurge: A Social History of Shopping,ECW Press, Toronto, Canada, pp. 90–93

- ^ a b "Window shopping: A photographic history of the shop window". Vienna Museum.

- ^ Marston, W.M. (September 1938). "You might as well enjoy it". The Rotarian. p. 23.

- ^ Laermans, R. (1993). "Learning to consume: early department stores and the shaping of the modern consumer culture, 1896–1914". Theory, Culture and Society. 10 (4): 79–102.

- ^ Sassatelli, R. (2007). Consumer culture: History, theory and politics. London: Sage Publications.

- ^ Kowinski, W. S. (1985). The Malling of America. New York: William Morrow.

- ^ Shields, R., ed. (1992). Lifestyle Shopping: The Subject of Consumption. London: Routledge.

- ^ Sassatelli, R. (2007). Consumer culture: History, theory and politics. London: Sage Publications.

- ^ a b Liu, Fang; Wang, Rong; Zhang, Ping; and Zuo, Meiyun, "A Typology of Online Window Shopping Consumers" (2012). PACIS 2012 Proceedings. Paper 128.

- ^ Ganesh, J.; Reynolds, K.E.; Luckett, M.; Pomirleanu, N. (2010). "Online shopper motivations, and e-store attributes: An examination of online patronage behavior and shopper typologies". Journal of Retailing. pp. 106–115.

- ^ Amien, Deb. "Why Unboxing Videos Are So Satisfying". Yahoo Tech. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ Google Trends: unboxing, accessed on 5 May 2010.