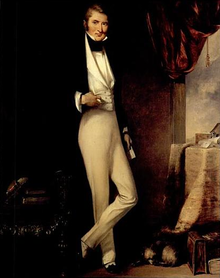

William Jardine (merchant)

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2015) |

William Jardine (24 February 1784 – 27 February 1843) was a Scottish opium trader and physician who co-founded the Hong Kong–based conglomerate Jardine, Matheson & Co. Educated in medicine at the University of Edinburgh, in 1802 Jardine obtained a diploma from the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. The next year, he became a surgeon's mate aboard the Brunswick belonging to the East India Company, and set sail for India. In May 1817, he abandoned medicine for trade.

Jardine was a resident in China from 1820 to 1839. His early success in Canton as a commercial agent for opium merchants in India led to his admission in 1825 as a partner in Magniac & Co., and by 1826 he controlled that firm's Canton operations. James Matheson joined him shortly afterwards with Magniac & Co. reconstituted as Jardine, Matheson & Co. in 1832. After Imperial Commissioner Lin Zexu destroyed 20,000 cases of opium seized from British traders in 1839, Jardine arrived in London that September to press Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston for a forceful response, which resulted in the First Opium War.[1]

Following his return to Britain from China, between 1841 and 1843, he was Member of Parliament for Ashburton representing the Whig party. Jardine died in 1843, bringing an end to his short political career.

Early life

[edit]Jardine, one of seven children, was born in 1784 on a small farm near Lochmaben, Dumfriesshire, Scotland.[2] His father, Andrew Jardine (abt. 1750- d. 1793), died when he was nine, leaving the family in some economic difficulty. Though struggling to make ends meet, Jardine's older brother David (1776-1827) provided him with money to attend school. Jardine began to acquire credentials at the age of sixteen.

In 1800 he entered the University of Edinburgh Medical School where he took classes in anatomy, medical practice, and obstetrics among others. While his schooling was in progress, Jardine was apprenticed to a surgeon who would provide housing, food, and the essential acquaintance with a hospital practice, with the money his older brother, David, provided.

He graduated from the Edinburgh Medical School on 2 March 1802, and was presented a full diploma from the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. He chose to join the service of the British East India Company (EIC) and in 1803, at the age of 19, boarded the East Indiaman Brunswick as a surgeon's mate in the East India Company's Maritime Marine Service.[3]: 208 Taking advantage of his employee's "cargo privilege", he traded successfully in cassia, cochineal and musk during his 14 years as a surgeon at the firm.[3]: 208

On his first voyage, Jardine met two men who would come to play a role in his future as a drug trafficking merchant. The first was Thomas Weeding, a fellow doctor, and surgeon of the Glatton, one of the other ships in the convoy. The second was 26-year-old Charles Magniac who had arrived in Guangzhou at the beginning of 1801 to supervise his father's watch business in Canton in partnership with Daniel Beale.

By leaving the East India Company in 1817,[1] Jardine was able to exploit the opportunity afforded by the company's policy of not transporting opium but contracting the trade out to free traders.[4]: 90 Jardine entered into partnership with retired surgeon Thomas Weeding and opium and cotton trader Framji Cowasji Banaji.[3]: 208 The firm did well and established Jardine's reputation as an able, steady and experienced private trader. One of Jardine's agents in Bombay, who would become his lifelong friend, was Parsee opium and cotton trader Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy.[3]: 208

Both men were on the Brunswick when the crew of a French ship forcibly boarded her. Jeejeebhoy long continued as a close business associate of Jardine and that a portrait of Jeejeebhoy hung in Jardines' Hong Kong office in the 1990s was tribute to that.[5]

In 1824, a very important opportunity arose for Jardine. Magniac & Co., one of the two most successful agency houses in Canton,[3]: 208 fell into disarray. Hollingworth Magniac, who succeeded his brother Charles Magniac after the latter's death in Paris, was in search of competent partners to join his firm as he was intent on leaving Asia.

He was also forced to have his brother, Daniel, resign from the firm after marrying his Chinese mistress. In later years, Jardine had helped Daniel by sending his young son Daniel Francis, his child by his Chinese wife, to Scotland for school. Magniac invited Jardine to join him in 1825 and, three years later, James Matheson joined the partnership.[3]: 208

Magniac returned to England in the late 1820s with the firm in the hands of Jardine and Matheson. Contrary to the practice at the time of retiring partners removing their capital from the firm, Magniac left his capital with the firm in trust to Jardine and Matheson. The firm carried on as Magniac & Co. until 1832 as the name Magniac was still formidable throughout China and India. Magniac wrote of William Jardine:

You will find Jardine a most conscientious, honourable, and kind-hearted fellow, extremely liberal and an excellent man of business in this market, where his knowledge and experience in the opium trade and in most articles of export is highly valuable. He requires to be known and to be properly appreciated.

Jardine, Matheson & Co.

[edit]

James Matheson joined Magniac & Co. from the firm Yrissari & Co where he was partner. After Francis Xavier de Yrissari's death, Matheson wound up the firm's affairs and closed shop. Yrissari, leaving no heir, had willed all his shares in the firm to Matheson. This created the perfect opportunity for Matheson to join in commerce with Jardine. Matheson proved a perfect partner for Jardine.

James Matheson and his nephew, Alexander Matheson, joined the firm Magniac and Co. in 1827, but their association was officially advertised on 1 January 1828. Jardine was known as the planner, the tough negotiator and strategist of the firm and Matheson was known as the organization man, who handled the firm's correspondence, and other complex articles including legal affairs.

Matheson was known to be behind many of the company's innovative practices. And both men were a study in contrasts, Jardine being tall, lean and trim while Matheson was short and slightly portly. Matheson had the advantage of coming from a family with social and economic means, while Jardine came from a much more humble background.

Jardine was tough, serious, detail-oriented and reserved while Matheson was creative, outspoken and jovial. Jardine was known to work long hours and was extremely business-minded, while Matheson enjoyed the arts and was very eloquent.

William C. Hunter wrote about Jardine, "He was a gentleman of great strength of character and of unbounded generosity." Hunter's description of Matheson was, "He was a gentleman of great suavity of manner and the impersonation of benevolence." But there were similarities in both men. Both men were hardworking, driven and single-minded in their pursuit of wealth.

Both men were also known to have continuously sent money home to less fortunate family members in Scotland and to have helped nephews by providing them work within the firm. Upon the death of his older brother, David, Jardine set up a fund for his brother's widow and arranged schooling for his four sons. In a letter to Magniac, Jardine wrote,

My only Brother has a very large family, three or four of them Boys, and as he has not the means of providing for them all, in the way I wish to see them provided for, I am desirous of having one of them here, to commence in the office, and work his way, by industry and application to business.

All four of David's sons moved on to work with Jardine, Matheson & Co. in Hong Kong and South China, starting as clerks and eventually becoming partners, managing partners or senior executives of the firm, locally known as taipan, a Chinese colloquial title meaning foreign-born senior manager.

But, it was their reputation for business probity, innovative management and strict fiscal policies that sustained their partnership's success in a period where businesses operated in a highly volatile and uncertain environment where the line between success and bankruptcy was extremely thin. Jardine was known for his legendary imperiousness and pride.

He was nicknamed by the locals "The Iron-headed Old Rat"[6] after being hit on the head by a club in Guangzhou. Jardine, after being hit, just shrugged off the injury with dour resilience. He had only one chair in his office in the "Creek Hong" in Canton,[2] and that was his own. Visitors were never allowed to sit, to impress upon them that Jardine was a very busy man.

Jardine was also known as a crisis manager. In 1822, during his visit to the firm's Guangzhou office, he found the local office in management crisis, with employees in near mutiny against the firm's officers. Jardine then proceeded to take temporary control and succeeded in putting the office in order in just a matter of days. Also a shrewd judge of character, Jardine was even able to persuade the Rev. Charles Gutzlaff, a Prussian missionary, to interpret for their ship captains during coastal smuggling of opium, using the idea that the reverend would best gather more converts during these smuggling operations. Matheson claimed to own the only piano in Asia and was also an accomplished player.

He was also responsible for removing one of the firm's ship captains for refusing to offload opium chests on the Sabbath, Matheson observed, "We have every respect for persons entertaining strict religious principles, but we fear that very godly people are not suited for the drug trade."

On 1 July 1832, Jardine, Matheson & Co., a partnership between Jardine and Matheson as senior partners, and Magniac, Alexander Matheson, Jardine's nephew Andrew Johnstone, Matheson's nephew Hugh Matheson, John Abel Smith, and Henry Wright, as the first partners, was formed in China, taking the Chinese name 'Ewo' (怡和) pronounced "Yee-Wo" and meaning "Happy Harmony".

The name was chosen as it had been used by the former Ewo Hong run by Chinese merchant Howqua, a business with an impeccable reputation.[7] The firm's operations included smuggling opium into China from Malwa, India, trading spices and sugar with the Philippines, exporting Chinese tea and silk to England, factoring and insuring cargo, renting out dockyard facilities and warehouse space, trade financing and other numerous lines of business and trade.

In 1834, Parliament ended the monopoly of the EIC on trade between Britain and China. Jardine, Matheson & Co. took this opportunity to fill the vacuum left by the East India Company. With its first voyage carrying raw silk, but ironically no tea, the ship Sarah (now owned by Thomas Weeding, but previously owned in partnership by Weeding, Jardine and Cowasjee) left for England, becoming the first free trader to arrive in England after the monopoly ceased. Jardine Matheson then began its transformation from a major commercial agent of the East India Company into the largest British trading hong (洋行), or firm, in Asia. William Jardine was now being referred to by the other traders as "taipan".

Jardine wanted the opium trafficking to expand in China. In 1834, working with the Chief Superintendent of Trade representing the British Empire, William, Lord Napier, tried unsuccessfully to negotiate with the Chinese officials in Canton. The Chinese Viceroy ordered the Canton offices where Napier was staying to be blockaded and the inhabitants including Napier to be held hostages. Lord Napier, a broken and humiliated man, was allowed to return to Macao by land and not by ship as requested. Suffering a fever, he died a few days later.

Jardine, who had good relations with Lord Napier, a Scottish peer, and his family, then took the initiative to use the debacle as an opportunity to convince the British government to use force to further open trade. In early 1835 he ordered James Matheson to leave for Britain to persuade the Government to take up strong action to further open up trade in China.

Matheson accompanied Napier's widow to England using an eye-infection as an excuse to return home. Matheson in England then extensively travelled to meet with several parties, both for government and for trade, to gather support for a war with China. Initially unsuccessful in his forays in England, he was brushed aside by the "Iron Duke" (Duke of Wellington), then the British Foreign Secretary, and reported bitterly to Jardine of being insulted by an arrogant and stupid man. However, his activities and widespread lobbying in several forums including Parliament sowed seeds that would lead to war in a few years.

Departure from China and breakdown of relations

[edit]Matheson returned to China in 1836 to prepare to take over the firm as Jardine was preparing to fulfill his temporarily delayed retirement. Jardine left Canton on 26 January 1839 for Britain[3]: 209 as retirement but in actuality to try to continue Matheson's work. The respect shown by other foreign opium traffickers to Jardine before his departure can be best illustrated in the following passage from a book by William C. Hunter.

A few days before Mr. Jardine’s departure from Canton, the entire foreign community entertained him at a dinner in the dining room of the East India Company’s Factory. About eighty persons of all nationalities, including India, were present, and they did not separate until several hours after midnight. It was an event frequently referred to afterwards amongst the residents, and to this day there are a few of us who still speak of it.

The Qing government was pleased to hear of Jardine's departure, then, being were more familiar with Jardine as the trading head and were quite unfamiliar with Matheson, proceeded to stop the opium trafficker. Lin Zexu, appointed specifically to suppress the drug trafficking in Guangzhou, stated, "The Iron-headed Old Rat, the sly and cunning ring-leader of the opium smugglers has left for The Land of Mist, of fear from the Middle Kingdom's wrath." He then ordered the surrender of all opium and the destruction of more than 20,000 cases of opium in Guangzhou, representing 50 per cent of the entire trade in opium in 1838.[4]: 91 He also ordered the arrest of opium trafficker Lancelot Dent, the head of Dent and Company (a rival company to Jardine Matheson). Lin also wrote to Queen Victoria, to submit in obeisance in the presence of the Chinese Emperor.

War and the Chinese surrender

[edit]Having arrived in London in September 1839,[3]: 209 Jardine's first order of business was to meet with Lord Palmerston. He carried with him a letter of introduction written by Superintendent Elliot that relayed a few of his credentials to Palmerston,

This gentleman has for several years stood at the head of our commercial community and he carries with him the esteem and kind wishes of the whole foreign society, honourably acquired by a long career of private charity and public spirit.

In 1839, Jardine successfully persuaded the British Foreign Minister, Lord Palmerston, to wage war on China, giving a full detailed plan for war, detailed strategic maps, battle strategies, the indemnifications and political demands from China and even the number of troops and warships needed. Aided by Matheson's nephew, Alexander Matheson (1805–1881) and MP John Abel Smith, Jardine met several times with Palmerston to argue the necessity for a war plan.

This plan was known as the Jardine Paper. In the 'Jardine Paper', Jardine emphasized several points to Palmerston in several meetings and they are as follows: There was to be complete compensation for the 20,000 chests of opium that Lin had confiscated, the conclusion of a viable commercial treaty that would prevent any further hostilities, and the opening of further ports of trade such as Fuzhou, Ningbo, Shanghai, and Keeson-chow.

It was also suggested by Jardine that should the need arise to occupy an island or harbor in the vicinity of Guangzhou, Hong Kong would be perfect because it provided an extensive and protected anchorage. As early as the mid-1830s, the island of Hong Kong had already been used for transhipment points by Jardine Matheson and other firms' ships.

Jardine clearly stated what he thought would be a sufficient naval and military force to complete the objectives he had outlined. He also provided maps and charts of the area. In a well calculated recommendation letter to Parliament, creating a precedent now infamously known as 'Gunboat Diplomacy', Jardine states:

No formal Purchase, – no tedious negotiations,...A firman insistently issued to Sir F. Maitland authorizing him to take and retain possession is all that is necessary, and the Squadron under his Command is quite competent to do both,...until an adequate naval and military force...could be sent out from the mother Country. When All this is accomplished – but not till then, a negotiation may be commenced in some such Terms as the following – You take my opium – I take your Islands in return – we are therefore Quits, – and thenceforth if you please let us live in friendly Communion and good fellowship. You cannot protect your Seaboard against Pirates and Buccaneers. I can – So let us understand Each other, and study to promote our mutual Interests.

Lord Palmerston, the Foreign Secretary who succeeded Wellington, decided mainly on the "suggestions" of Jardine to dispatch a military expedition to China. In June 1840, a fleet of 16 Royal Navy warships and British merchantmen, many of the latter leased from Jardine Matheson & Co., arrived at Canton and the First Opium War quickly broke out. For the next two years, British forces engaged the Chinese military in numerous battles as part of a series of military campaigns intended to bring the Qing government to the negotiating table. Eventually, the British pushed far enough up north to threaten the Imperial Palace in Beijing itself. The Qing government, forced to surrender, gave in to the demands of the British. Richard Hughes, in Hongkong: A Borrowed Place, A Borrowed Time, stated "William Jardine would have made his mark as admirably as a soldier as he did as a Tai-pan." Lord Palmerston wrote,

To the assistance and information which you and Mr. Jardine so handsomely afforded us it was mainly owing that we were able to give our affairs naval, military and diplomatic, in China those detailed instructions which have led to these satisfactory results.

In 1843, the Treaty of Nanking was signed by official representatives of both Britain and China. It allowed the opening of five major Chinese ports, granted extraterritoriality to foreigners and their activities in China, indemnification for the opium destroyed and completed the formal acquisition of the island of Hong Kong, which had been officially taken over as a trading and military base since 26 January 1841, though it had already been used years earlier as a transhipment point. Trade with China, especially in the illegal opium, grew, and so did the firm of Jardine, Matheson & Co., which was already known as the Princely Hong for being the largest British trading firm in East Asia.

By 1841, Jardine had 19 intercontinental clipper ships, compared to close rival Dent and Company with 13. He also had hundreds of small ships, lorchas and small smuggling craft for coastal and upriver smuggling. In 1841, Jardine was elected to the House of Commons, a Whig Member of Parliament (MP) representing Ashburton in Devon.[3]: 209 He was also a partner, along with Magniac, in the merchant banking firm of Magniac, Smith & Co., later renamed Magniac, Jardine & Co.,[8] the forerunner of the firm Matheson & Co. Despite his nominal retirement, Jardine was still very much active in business and politics and built a townhouse in 6 Upper Belgrave Street, then a new upscale residential district in London near Buckingham Palace. He had also bought a country estate, Lanrick Castle, in Perthshire, Scotland.[3]: 209

Death and legacy

[edit]In late 1842, Jardine's health had rapidly deteriorated due to colon cancer. In the latter part of the year, Jardine was already bedridden and in great pain. He was assisted by his nephew, Andrew Johnstone and later on by James Matheson in his correspondence. Despite his illness, Jardine was still very active in keeping an eye on business, politics and current affairs, and continued to welcome a steady stream of visits from family members, business partners, political associates and his constituents.

He died on 27 February 1843, just three days after his 59th birthday, one of the richest and most powerful men in Britain and Member of Parliament. Jardine's funeral was attended by a very large gathering of family, friends, government and business personalities, many of whom Jardine had helped in his lifetime.

Jardine, a bachelor, willed his estate to his siblings and his nephews. Though gleaning from Oxford University Press' immense collection of Jardine Matheson's correspondence from its earliest years, it can be speculated that Jardine had an illegitimate child, a daughter, with a 'Mrs. Ratcliffe' who was provided with an annual pension and shares with Jardine's firms which was later on cashed out years after Jardine's death. Jardine had provided extensive correspondence with various associates in London instructing to carry out provisions to Mrs. Ratcliffe and her daughter, named Matilda Jane or 'Tilly' as Jardine affectionately called her in his letters. There were also letters from Tilly to Jardine requesting for additional monetary assistance. An older nephew, Andrew Johnstone, administered Jardine's issue.

His other nephews David, Joseph, Robert and Andrew Jardine, all sons of Jardine's older brother David, continued to assist James Matheson in running Jardines. Matheson retired as taipan in 1842 and handed over control of the firm to his nephew Sir Alexander Matheson, who was also known as of the same capacity and competence as the elder Jardine and Matheson. David Jardine, another nephew of Jardine, became taipan after Sir Alexander Matheson and was one of the first two unofficial members appointed to the Legislative Council in Hong Kong.[9]: 261 David in turn would hand over to his brother Sir Robert control of the firm. Joseph succeeded Robert as taipan.

Sir Robert Jardine (1825–1905) is the ancestor of the Buchanan-Jardine branch of the family. A descendant of Sir Robert, Sir John Buchanan-Jardine, sold his family's 51% holding in Jardine, Matheson and Co. for $84 million at the then prevailing exchange rate in 1959. A great-nephew of Jardine who would be taipan from 1874 to 1886, William Keswick (1834–1912), is the ancestor of the Keswick branch (pronounced Ke-zick) of the family.

Keswick is a grandson of Jardine's older sister, Jean Johnstone. Keswick was responsible for opening the Japan office of the firm in 1859 and also expanding the Shanghai office. James Matheson returned to England to fill up the Parliament seat left vacant by Jardine and to head up the firm Matheson & Co., previously known as Magniac, Jardine & Co., in London, a merchant bank and Jardines' agent in England.

In 1912, Jardine, Matheson & Co. and the Keswicks would eventually buy out the shares of the Matheson family in the firm although the name is still retained. The company was managed by several of Jardine's family members and their descendants throughout the decades, including the Keswicks, Buchanan-Jardines, Landales, Bell-Irvings, Patersons, Newbiggings and Weatheralls.

Notable Jardines managing directors, or taipans, included Sir Alexander Matheson, 1st Baronet, David Jardine, Robert Jardine, William Keswick, James Johnstone Keswick, Ben Beith, David Landale, Sir John Buchanan-Jardine, Sir William Johnstone "Tony" Keswick, Hugh Barton, Sir Michael Herries, Sir John Keswick, Sir Henry Keswick, Simon Keswick and Alasdair Morrison. There was a point in time in the early 20th century that the firm had two taipans at the same time, one in Hong Kong and one in Shanghai, to effectively manage the firm's extensive affairs in both locations. Both taipans were responsible only to the senior partner or proprietor in London who was normally a retired former taipan and an elder member of the Jardine family.

Today, the Jardine Matheson Group is still very much active in Hong Kong, being one of the largest conglomerates in Hong Kong and its largest employer, second only to the government. Several landmarks in present-day Hong Kong are named after the firm and the founders Jardine and Matheson like Jardine's Bazaar, Jardine's Crescent, Jardine's Bridge, Jardine's Lookout, Yee Wo Street, Matheson Street, Jardine House and the Noon Day Gun. In 1947, a secret Trust was formed by members of the family to retain effective control over the company.

Jardine, Matheson and Co. offered its shares to the public in 1961 under the tenure of Hugh Barton and was oversubscribed 56 times. The Keswick family, in consortium with several London-based banks and financial institutions, bought out the controlling shares of the Buchanan-Jardine family in 1959, but subsequently sold most of the shares during the 1961 public offering, retaining only about 10% of the company. The company had its head office redomiciled to Bermuda in 1984 under the tenure of Simon Keswick.

The present Chairman of Jardine Matheson Holdings Ltd, Sir Henry Keswick, who is based in the UK, was the company's taipan from 1970 (aged 31) to 1975 and was the 6th Keswick to be taipan of the company. His brother Simon was the company's taipan from 1983 to 1988 and is the 7th Keswick to be taipan. Both brothers are the fourth generation of Keswicks in the company. The organizational structure of Jardines has changed almost totally, but members of Jardine's family still control the firm through a complex cross-shareholding structure, several allied shareholders and a secretive 1947 Trust.

Family tree

[edit]

See also

[edit]- Buchanan-Jardine baronets – branch of Jardine family from William's brother David Jardine.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Grace, Richard J.. "Jardine, William (1784–1843)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37595. Accessed 29 April 2010.

- ^ a b Keswick, Maggie; Weatherall, Clara (2008). The thistle and the jade:a celebration of 175 years of Jardine Matheson. Francis Lincoln Publishing. ISBN 9780711228306. p.18 Online version at Google books

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Le Pichon, Alain (2012). May Holdsworth; Christopher Munn (eds.). Dictionary of Hong Kong Biography. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9789888083664.

- ^ a b Napier, Priscilla (1995). Barbarian Eye, Lord Napier in China 1834. London: Brassey's. ISBN 9781857531169.

- ^ "Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy: China, William Jardine, the Celestial, and other HK connections". The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Palmer, Roundell, 1st Earl of Selborne (1840). Statement of Claims of the British Subjects Interested in Opium Surrendered to Captain Elliot at Canton for the Public Service. Cornhill, London: Pelham, Richardson. p. 128, Memorial of Hew Kew, August 1836.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Cheong, W.E. (1997). The Hong merchants of Canton: Chinese merchants in Sino-Western trade. Routledge. ISBN 0700703616. p.122 Online version at Google books

- ^ "William Jardine". Stanford University. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ Norton-Kyshe, James William (1898). History of the Laws and Courts of Hong Kong. Vol. I. London: T Fisher Unwin.

References

[edit]- William Jardine and other Jardine taipans are fictionally portrayed in author James Clavell's popular fiction novels Tai-Pan (1966), Gai-Jin (1993), Noble House (1981) and Whirlwind (1987).

- China Trade and Empire: Jardine, Matheson & Co. and the Origins of British Rule in Hong Kong 1827-1843 by Alain Le Pichon

- Jardine Matheson Archives Cambridge Library

- Jardine Matheson: Traders of the Far East by Sir Robert Blake

- The Thistle and the Jade by Maggie Keswick

Further reading

[edit]- Richard J. Grace. Opium and Empire: The Lives and Careers of William Jardine and James Matheson (McGill-Queen's University Press; 2014) 476 pages.

External links

[edit]- 1784 births

- 1843 deaths

- Alumni of the University of Edinburgh

- British expatriates in China

- British people of the First Opium War

- History of foreign trade in China

- Jardines (company)

- Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Ashburton

- People from Dumfries and Galloway

- Scottish surgeons

- UK MPs 1841–1847

- Whig (British political party) MPs for English constituencies

- Smugglers

- Naval surgeons

- British East India Company people

- 19th-century Scottish merchants

- Scottish company founders