Wikipedia:No angry mastodons

This is an essay on the Civility policy. It contains the advice or opinions of one or more Wikipedia contributors. This page is not an encyclopedia article, nor is it one of Wikipedia's policies or guidelines, as it has not been thoroughly vetted by the community. Some essays represent widespread norms; others only represent minority viewpoints. |

This page in a nutshell:

|

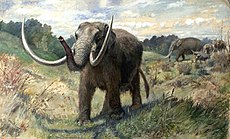

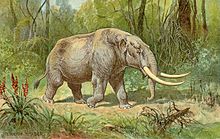

The fight-or-flight response may have helped our nomadic ancestors to escape from angry mastodons, but it isn't constructive in an online encyclopedia.[1] Wikipedia collaboration occurs between geographically isolated people on the Internet. Nonetheless, sometimes editors get angry and feel a natural urge to respond with an immediate retort ("fight"). The urge is accompanied by a rapid heart rate, dilated pupils, and other physiological changes associated with the body's release of epinephrine. Or, they get anxious or bored and simply log off ("flight").

One of the best experiences at Wikipedia happens among editors with deep differences. People don't have to agree about a topic to collaborate on a great article. All it takes is mutual respect and a willingness to abide by referenced sources and site policies. If you think you're right, dig up the very best evidence you can find and put that in the article or add it to the discussion. Let the other side's best evidence be a challenge to raise your own standards and always bear the big picture in mind: we're here to provide information for nonspecialists to teach them about the topic.

There are several informal ways to de-escalate conflicts and defuse disputes.

Edit when you're at your best

[edit]All humans share the ancient fight or flight instinct. It feels very real but it isn't the smartest part of our brains; it's something we have in common with reptiles. When tempers start to flare and an editor gets hot under the collar, it's a good idea to remember that the mastodons have all been extinct for thousands of years. Nobody ever got trampled to death because they were editing an encyclopedia.

Get a glass of water. Walk around the block. Go wash the dishes. The feeling will pass after a few minutes and you will be less likely to write things you would regret afterward.

It is easy to tell when an editor acted in anger and haste. The edit contains inflammatory language and is poorly written or appears to ignore other editors' input. The best way to resolve this is to remain calm, focus on the subject matter, and allow the other editor a graceful retreat from a momentary lapse. Wikipedia:Resolving disputes can address persistent problems.

Edit on a full stomach

[edit]Somehow people tend to be smarter, nicer, and happier after they've eaten a meal, particularly pizza. Even a light snack can take the edge off aggression.

Edit when you're fully awake

[edit]Sleep deprivation does screwy things to your mind, and to your writing skills. If you're jet-lagged, exhausted after a long day, or up at 3 am after finishing an arduous term paper, please don't edit! Put your hands in the air and step away from Wikipedia. If you edit while sleep-deprived, you could end up doing things as banal as making dumb mistakes that make you feel stupid when they get reverted, to things as potentially damaging as losing your temper, blowing your top, insulting all your friends and colleagues and turning them into enemies.

Drink minimal amounts of alcohol

[edit]

People are rarely smarter and nicer after consuming large quantities of alcohol, even though they may feel smarter and nicer. Fuses may be shorter and inhibitions lower; be cautious about editing after drinking.

Write your own stress scale

[edit]One way to keep Wikipedia in perspective is to write your own Richter scale for stress. Choose an event from your life for every number, starting with 1 for something like I stub my toe and ending with 10 for the worst thing that ever happened to you such as a death in the family. Where would you rank a broken arm or the loss of a job? Where's Wikipedia? It's good to keep things in perspective.

If all else fails

[edit]Consider writing on a text editor on your local computer. You can then see what you've said later and decide how and whether to insert it into the Wikipedia article. If you use your text editor (or liquor) liberally, you can adopt this mantra: Write drunk, edit sober.

Be considerate of the opposing view

[edit]

When discussing a disagreement on a talk page, it is better to advocate one's own perspective than to characterize an opposing view. People rarely do justice to opinions they disagree with. Edit wars can start when one party thinks he or she understands both sides, but actually mischaracterizes key aspects of the opposition. The opposing side's assumption of good faith soon expires if the problem persists. It is time to step back if other editors respond with "That's not what I said" or "Please stop putting words in my mouth."

Rather than asserting, "I believe ABC and you believe XYZ," a better approach is to say "I believe ABC. What do you believe?" or "I believe ABC. If I understand correctly, your position is XYZ."

This is important because there is a very human tendency to construct straw man arguments for opinions one disagrees with. Editors who hold opposing views can collaborate toward a balanced and neutral article by each contributing a good presentation for their own side, so long as neither constitutes original research.

A related mistake is to speculate about the intellectual capacity or the mental health of other editors. People do not rise to their best selves when they are reminded of their worst selves or accused of faults they do not possess. Editors who make these accusations exhibit poor self-control. Leave the angry mastodons in the Ice Age and focus on the article.

On the positive side, many Wikipedians set aside their personal beliefs when they act as editors. Sometimes the fair understanding of site policy means a particular source they agree with just fails to meet Wikipedia:Verifiability, or they delete something they really like because it violates Wikipedia:Neutral point of view, or they play devil's advocate and cite references that contradict their own beliefs because an article has a shortage of contributors and they need to balance other statements. It is best to suppose that each editor observes these high standards until proved otherwise.

Double-check the facts

[edit]

When people feel angry they tend to believe they already have enough information to justify the anger. If another editor complains about an article text, take a few seconds and check the history file before responding. Maybe a copyedit accidentally changed part of the article's meaning. The complaint might be valid even if the editor is rude. A friendly "I think I've found what caused the problem" post often calls a truce before an edit war can begin.

Likewise, no matter how certain your recollection feels about what you did several weeks ago, memories are faulty. Can you recall what you ate for lunch on the second Tuesday of last month? Probably not. Read the old posts. Few Wikimoments are more embarrassing than to insist, "I didn't add that to the article!" and then see another editor contradict that by quoting your date stamp and edit summary.

Editors make the oddest mistakes when the angry mastodons seem to be roaming. They take offense at a talk page post and blame the wrong person. They debate about a source while they misidentify the source. As a general rule, the times when fact checking feels unnecessary are the same times when huge goofs are most probable (and likely to get expressed in ways that make graceful retreat impossible). If another editor has been obnoxious and you're absolutely certain that mastodons were the closest extinct relative of the elephant, it's better to catch your own mistake than to read someone else's resentful mention of the woolly mammoth.

Look for an opposing truth

[edit]As wacky as human beings occasionally are, there's a good chance that even someone you are finding difficult has something valid to say. People are often better at identifying problems than at proposing solutions. So when a proposed solution appears unworkable, one good approach is to look for a weakness in the article that might have caught the other editor's attention. Instead of battling over differences, seek the areas of agreement. Express those agreements. Seek the things you can praise with sincerity. Maybe the opposing editor is an intelligent and mostly rational person who approaches the topic from a different point of view.

Disagree respectfully

[edit]Mundane editorial disagreements are most likely to resolve quickly and productively when editors observe the following suggestions:

- Remain polite.

- Solicit feedback and ask questions. This can be done without any formal procedure on article and user talk pages. For instance:

One question: why didn't you move the article to Siege of Orleans? That is certainly the more appropriate name. So, before I move it, I thought I would ask if there was some reason for your not having moved it already.

- Keep the discussion focused. Concentrate on a small set of related matters and resolve them to the satisfaction of all parties. Afterward open unrelated issues as a separate discussion.

- Use bullet points to organize a discussion that includes several matters.

- Focus on the subject rather than on the personalities of the editors.

The ewwww factor

[edit]If something's wrong and it's not getting fixed, please be patient and keep working on fixing it the right way. If you let your own standards drop because you get frustrated, people will go ewwww and walk away. Then it'll take even longer to get your problem solved. That's not a happy place to be.

Defuse personal attacks

[edit]Avoid angry mastodons

[edit]Sometimes editors perceive a personal attack where none actually exists. Usually this confusion happens when an editor misreads a personal attack into a detailed post about a content disagreement. This is one of the shortcomings of the fight-or-flight response. People don't concentrate very well when they get angry. So an upset editor sometimes perceives an insult to their competence in a statement such as "The 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica contradicts your unsourced assertion."

On one hand, making "you" statements does stir the pot; a better way to phrase the same position is to not personalize it: Better to remove personal pronouns entirely and say, "The 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica contradicts the statement [foobar]; can [foobar] be sourced?" But, on the other hand, the person feeling attacked has a responsibility to avoid "mock outrage", the insistence that something is a slight when the writer clarifies that was not intended as such.

When people are involved in disputes there is a tendency to take offense at statements that are either not intended as slights—or that transgress the norms of discussion only in a technical sense—but are not in fact hurtful to the target of the comment. When dealing with strangers, particularly through text communication—where emotions are hard to judge—it is better to ask yourself, "How might that comment have been a friendly gesture by a well-meaning editor?", rather than, "How might the comment have been a challenge?" This is the core of assuming good faith; start with a belief that the other party did not intend harm.

If you feel yourself getting red in the face and skimming rather than reading, take a break. In a calmer moment, it will be clear whether the right response is to cite a more recent piece of scholarship instead of making a complaint about editor courtesy.

To quote well-known American jurist Alex Kozinski, in a judicial opinion castigating two parties for trumping up allegations of defamation against each other when their underlying conflict was a simple trademark dispute, "the parties are advised to chill".

Clarify humor

[edit]

Some people use humor as a weapon. Other times a joke just falls flat or an editor—rightly or wrongly—perceives a hidden insult. In the spirit of assuming good faith, ask for clarification before taking offense. Remember that intentions may not come across as well in text as in face-to-face conversation.

Be the voice of reason

[edit]Resist the temptation to respond in kind to a perceived personal attack. Identify the specific problem behavior and ask the person responsible to stop. People often improve their manners when other editors are polite.

Polite requests to end personal attacks are particularly effective when they come from a neutral third party. This usually takes the sting out of an insult and returns the dialogue to a productive direction. The approach works best when all editors are active contributors to the same page, when the intervening editor acts early, and when the intervening editor is respected for fairness.

Be a class act

[edit]Occasionally one editor acts in bad faith and actively baits another. If you think you're the target of baiting, don't respond in kind. Maybe the other person is just having a bad day. If the problem continues and you need to request administrative intervention, you'll maximize your chances of getting assistance if your own responses have always been civil and reasonable. It can be a test of character to handle things this way when it seems like help is slow in coming, but it's simpler and faster to resolve a one-sided dispute than a two-sided dispute. A classy response earns the respect of the site's productive editors.

Move references to the project page

[edit]A few Wikipedia articles collect more references on the talk page than in the article itself. This happens when two or more editors disagree on the subject matter, yet proceed from a shared assumption that the article should present only a conclusion of the dispute. In many cases this is a mistaken assumption.

If both sides of the dispute cite mainstream experts, then the discussion and its references can move to the article in suitably encyclopedic language. The editors need not reach a consensus or a compromise. It is enough to describe the controversy in neutral terms and to offer the best evidence for both sides. This approach can enrich the article.

For example, regarding the Battle of Borodino between Russia and France in 1812, opinions differ about whether to call this a French victory. This can become an interesting springboard for analysis of military tactics and strategy and for studying the decline of Napoleon.

Conclusion

[edit]A little bit of ancient instinct remains within every modern human. Juan Luis Arsuaga writes in The Neanderthal's Necklace: In Search of the First Thinkers (2002) that "somewhere within us all hides a prehistoric human who still responds to the call of the wild".[2] The fight-or-flight response evolved to help humans and other mammals respond to life-threatening situations. Unfortunately, it can also cause people to overreact to non-life-threatening stressors.[3] Collaboration through Wikipedia involves channeling these ancient impulses in more productive directions.

See also

[edit]- Wikipedia:No angry mastodons just madmen – follow-up essay by Wikid77

- Wikipedia:Advice for hotheads

- Wikipedia:Beware of the tigers

- Wikipedia:Beyond civility

- Wikipedia:Don't be a fanatic

- Wikipedia:Don't be a jerk

- Wikipedia:Don't be inconsiderate

- Wikipedia:Don't-give-a-fuckism

- Wikipedia:Don't take the bait

- Wikipedia:Five pillars

- Wikipedia:How to lose

- Wikipedia:Lamest edit wars

- Wikipedia:No climbing the Reichstag dressed as Spider-Man

- Wikipedia:Please be a giant dick, so we can ban you

- Wikipedia:Please do not bite the newcomers

- Wikipedia:Requests for medication

- Wikipedia:Staying cool when the editing gets hot

- Wikipedia:The world will not end tomorrow

- Wikipedia:Tips for the angry new user

Notes

[edit]- ^ This assertion may be unfair to mastodons. According to Diana Reiss of Columbia University, elephants are among the species that "are thought to possess the highest forms of empathy and altruism in the animal kingdom." No mastodons were available for study. The Guardian accessed 31 October 2006

- ^ p. viii

- ^ "Understanding the stress response". Harvard Medical School. 18 March 2016.