My Fair Lady

| My Fair Lady | |

|---|---|

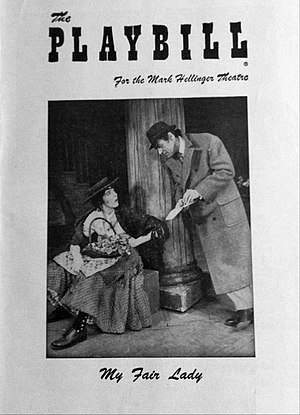

Original Broadway Poster by Al Hirschfeld | |

| Music | Frederick Loewe |

| Lyrics | Alan Jay Lerner |

| Book | Alan Jay Lerner |

| Basis | Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw |

| Productions | 1956 Broadway 1957 US tour 1958 West End 1976 Broadway 1978 UK tour 1979 West End 1980 US tour 1981 Broadway 1993 US tour 1993 Broadway 2001 West End 2005 UK tour 2007 US tour 2018 Broadway 2019 US tour 2022 West End |

| Awards | 1957 Tony Award for Best Musical 2002 Laurence Olivier Award for Best Musical Revival |

My Fair Lady is a musical with a book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Loewe. The story, based on George Bernard Shaw's 1913 play Pygmalion and on the 1938 film adaptation of the play, concerns Eliza Doolittle, a Cockney flower girl who takes speech lessons from professor Henry Higgins, a phonetician, so that she may pass as a lady. Despite his cynical nature and difficulty understanding women, Higgins grows attached to her.

The musical's 1956 Broadway production was a notable critical and popular success, winning six Tony Awards, including Best Musical. It set a record for the longest run of any musical on Broadway up to that time and was followed by a hit London production. Rex Harrison and Julie Andrews starred in both productions. Many revivals have followed, and the 1964 film version won the Academy Award for Best Picture.

Plot

[edit]Act I

[edit]In Edwardian London, Eliza Doolittle is a flower girl with a thick Cockney accent. The noted phonetician Professor Henry Higgins encounters Eliza at Covent Garden and laments the vulgarity of her dialect ("Why Can't the English?"). Higgins also meets Colonel Pickering, another linguist, and invites him to stay as his houseguest. Eliza and her friends wonder what it would be like to live a comfortable life ("Wouldn't It Be Loverly?").

Eliza's dustman father, Alfred P. Doolittle, stops by the next morning searching for money for a drink ("With a Little Bit of Luck"). Soon after, Eliza comes to Higgins's house, seeking elocution lessons so that she can get a job as an assistant in a florist's shop. Higgins wagers Pickering that, within six months, by teaching Eliza to speak properly, he will enable her to pass for a proper lady.

Eliza becomes part of Higgins's household. Though Higgins sees himself as a kindhearted man who merely cannot get along with women ("I'm an Ordinary Man"), to others he appears self-absorbed and misogynistic. Eliza endures Higgins's tyrannical speech tutoring. Frustrated, she dreams of different ways to kill him ("Just You Wait"). Higgins's servants lament the stressful atmosphere ("The Servants' Chorus").

Just as Higgins is about to give up on her, Eliza suddenly recites one of her diction exercises in perfect upper-class style ("The Rain in Spain"). Though Mrs Pearce, the housekeeper, insists that Eliza go to bed, she declares she is too excited to sleep ("I Could Have Danced All Night").

For her first public tryout, Higgins takes Eliza to his mother's box at Ascot Racecourse ("Ascot Gavotte"). Though Eliza shocks everyone when she forgets herself while watching a race and reverts to foul language, she does capture the heart of Freddy Eynsford-Hill. Freddy calls on Eliza that evening, and he declares that he will wait for her in the street outside Higgins' house ("On the Street Where You Live").

Eliza's final test requires her to pass as a lady at the Embassy Ball. After more weeks of preparation, she is ready. ("Eliza's Entrance"). All the ladies and gentlemen at the ball admire her, and the Queen of Transylvania invites her to dance with the prince ("Embassy Waltz"). A Hungarian phonetician, Zoltan Karpathy, attempts to discover Eliza's origins. Higgins allows Karpathy to dance with Eliza.[1]

Act II

[edit]The ball is a success; Karpathy has declared Eliza to be a Hungarian princess. Pickering and Higgins revel in their triumph ("You Did It"), failing to pay attention to Eliza. Eliza is insulted at receiving no credit for her success, packing up and leaving the Higgins house. As she leaves she finds Freddy, who begins to tell her how much he loves her, but she tells him that she has heard enough words; if he really loves her, he should show it ("Show Me").

Eliza and Freddy return to Covent Garden but she finds she no longer feels at home there. Her father is there as well, and he tells her that he has received a surprise bequest from an American millionaire, which has raised him to middle-class respectability, and now must marry his lover. Doolittle and his friends have one last spree before the wedding ("Get Me to the Church on Time").

Higgins awakens the next morning. He finds himself out of sorts without Eliza. He wonders why she left after the triumph at the ball and concludes that men (especially himself) are far superior to women ("A Hymn to Him"). Col. Pickering is concerned about Eliza's well-being, calling the police as well as contacting an old chum he believes will help them track her down.

Higgins despondently visits his mother's house, where he finds Eliza. Eliza declares she no longer needs Higgins ("Without You"). As Higgins walks home, he realizes he's grown attached to Eliza ("I've Grown Accustomed to Her Face"). At home, he sentimentally reviews the recording he made the day Eliza first came to him for lessons, hearing his own harsh words. Eliza suddenly appears in his home. In suppressed joy at their reunion, Professor Higgins scoffs and asks, "Eliza, where the devil are my slippers?"

Characters and original Broadway cast

[edit]The original cast of the Broadway stage production:[2]

- Eliza Doolittle, a young Cockney flowerseller – Julie Andrews

- Henry Higgins, a professor of phonetics – Rex Harrison

- Alfred P. Doolittle, Eliza's father, a dustman – Stanley Holloway

- Colonel Hugh Pickering, Henry Higgins's friend and fellow phoneticist – Robert Coote

- Mrs. Higgins, Henry's socialite mother – Cathleen Nesbitt

- Freddy Eynsford-Hill, a young socialite and Eliza's suitor – John Michael King

- Mrs. Pearce, Higgins's housekeeper – Philippa Bevans

- Zoltan Karpathy, Henry Higgins's former student and rival – Christopher Hewett

Musical numbers

[edit]|

Act I[2]

|

Act II

|

Background

[edit]In the mid-1930s, film producer Gabriel Pascal acquired the rights to produce film versions of several of George Bernard Shaw's plays, Pygmalion among them. However, Shaw, having had a bad experience with The Chocolate Soldier, a Viennese operetta based on his play Arms and the Man, refused permission for Pygmalion to be adapted into a musical. After Shaw died in 1950, Pascal asked lyricist Alan Jay Lerner to write the musical adaptation. Lerner agreed, and he and his partner Frederick Loewe began work. But they quickly realised that the play violated several key rules for constructing a musical: the main story was not a love story, there was no subplot or secondary love story, and there was no place for an ensemble.[3] Many people, including Oscar Hammerstein II, who, with Richard Rodgers, had also tried his hand at adapting Pygmalion into a musical and had given up, told Lerner that converting the play to a musical was impossible, so he and Loewe abandoned the project for two years.[4]

During this time, the collaborators separated, and Pascal died. Lerner had been trying to musicalize Li'l Abner when he read Pascal's obituary and found himself thinking about Pygmalion again.[5] When he and Loewe reunited, everything fell into place. All of the insurmountable obstacles that had stood in their way two years earlier disappeared when the team realized that the play needed few changes apart from (according to Lerner) "adding the action that took place between the acts of the play".[6] They then excitedly began writing the show. However, Chase Manhattan Bank was in charge of Pascal's estate, and the musical rights to Pygmalion were sought both by Lerner and Loewe and by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, whose executives called Lerner to discourage him from challenging the studio. Loewe decided, "We will write the show without the rights, and when the time comes for them to decide who is to get them, we will be so far ahead of everyone else that they will be forced to give them to us."[7] For five months Lerner and Loewe wrote, hired technical designers, and made casting decisions. The bank, in the end, granted them the musical rights.

Various titles were suggested for the musical. Dominic McHugh wrote: "During the autumn of 1955, the show [was] typically referred to as My Lady Liza, and most of the contracts refer to this as the title."[8] Lerner preferred My Fair Lady, relating both to one of Shaw's provisional titles for Pygmalion and to the final line of every verse of the nursery rhyme "London Bridge Is Falling Down". Recalling that the Gershwins' 1925 musical Tell Me More had been titled My Fair Lady in its out-of-town tryout, and also had a musical number under that title, Lerner made a courtesy call to Ira Gershwin, alerting him to the use of the title for the Lerner and Loewe musical.[citation needed]

Noël Coward was the first to be offered the role of Henry Higgins, but he turned it down, suggesting the producers cast Rex Harrison instead.[9] After much deliberation, Harrison agreed to accept the part. Mary Martin was an early choice for the role of Eliza Doolittle, but declined the role.[10] Young actress Julie Andrews was "discovered" and cast as Eliza after the show's creative team went to see her Broadway debut in The Boy Friend.[11] Moss Hart agreed to direct after hearing only two songs. The experienced orchestrators Robert Russell Bennett and Philip J. Lang were entrusted with the arrangements, and the show quickly went into rehearsal.[citation needed]

The musical's script used several scenes that Shaw had written especially for the 1938 film version of Pygmalion, including the Embassy Ball sequence and the final scene of the 1938 film rather than the ending for Shaw's original play.[12] The montage showing Eliza's lessons was also expanded, combining both Lerner's and Shaw's dialogue. The artwork on the original Broadway poster (and the sleeve of the cast recording) is by Al Hirschfeld, who drew the playwright Shaw as a heavenly puppetmaster pulling the strings on the Henry Higgins character, while Higgins in turn attempts to control Eliza Doolittle.[13]

Productions

[edit]Original Broadway production

[edit]

The musical had its pre-Broadway tryout at New Haven's Shubert Theatre. At the first preview Rex Harrison, who was unaccustomed to singing in front of a live orchestra, "announced that under no circumstances would he go on that night...with those thirty-two interlopers in the pit".[14] He locked himself in his dressing room and came out little more than an hour before curtain time. The whole company had been dismissed but were recalled, and opening night was a success.[15] My Fair Lady then played for four weeks at the Erlanger Theatre in Philadelphia, beginning on February 15, 1956.

The musical premiered on Broadway March 15, 1956, at the Mark Hellinger Theatre in New York City. It transferred to the Broadhurst Theatre and then The Broadway Theatre, where it closed on September 29, 1962, after 2,717 performances, a record at the time. Moss Hart directed and Hanya Holm was choreographer. In addition to stars Rex Harrison, Julie Andrews and Stanley Holloway, the original cast included Robert Coote, Cathleen Nesbitt, John Michael King, and Reid Shelton.[16] Harrison was replaced by Edward Mulhare in November 1957 and Sally Ann Howes replaced Andrews in February 1958.[17][18] By the start of 1959, it was the biggest grossing Broadway show of all-time with a gross of $10 million.[19]

The Original Cast Recording, released on April 2, 1956, was the best-selling album in the United States in 1956.[20]

Original London production

[edit]The West End production, in which Harrison, Andrews, Coote, and Holloway reprised their roles, opened on April 30, 1958, at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, where it ran for five and a half years[21] (2,281 performances). Edwardian musical comedy star Zena Dare made her last appearance in the musical as Mrs. Higgins.[22] Leonard Weir played Freddy. Harrison left the London cast in March 1959, followed by Andrews in August 1959 and Holloway in October 1959.

1970s revivals

[edit]The first Broadway revival opened at the St. James Theatre 20 years after the original, on March 25, 1976, and ran there until December 5, 1976; it then transferred to the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre, running from December 9, 1976, until it closed on February 20, 1977, after a total of 377 performances and 7 previews. The director was Jerry Adler, with choreography by Crandall Diehl, based on the original choreography by Hanya Holm. Ian Richardson starred as Higgins, with Christine Andreas as Eliza, George Rose as Alfred P. Doolittle and Robert Coote recreating his role as Colonel Pickering.[16] Both Richardson and Rose were nominated for the Tony Award for Best Actor in a Musical, with the award going to Rose.

A Cameron MacKintosh revival opened at London's Adelphi Theatre in October 1979, following a national tour. Originated at the Haymarket Theatre Leicester, the production was created under a new agreement with The Arts Council to tour West End standard productions. It featured Tony Britton as Higgins, Liz Robertson as Eliza, Dame Anna Neagle as Higgins's mother, Peter Bayliss as Doolittle, Richard Caldicot as Pickering and Peter Land as Freddy. It was directed by Robin Midgley,[23][24][25] with sets by Adrian Vaux, costumes by Tim Goodchild and choreography by Gillian Lynne.[26] Britton and Robertson were both nominated for Olivier Awards.[27]

1981 and 1993 Broadway revivals

[edit]The second Broadway revival of the original production opened at the Uris Theatre on August 18, 1981, and closed on November 29, 1981, after 119 performances and 5 previews. Rex Harrison recreated his role as Higgins, with Jack Gwillim as Pickering, Milo O'Shea as Doolittle, and Cathleen Nesbitt, at 93 years old reprising her role as Mrs. Higgins. The revival co-starred Nancy Ringham as Eliza. The director was Patrick Garland, with choreography by Crandall Diehl, recreating the original Hanya Holm dances.[16][28]

A new revival directed by Howard Davies opened at the Virginia Theatre on December 9, 1993, and closed on May 1, 1994, after 165 performances and 16 previews. The cast starred Richard Chamberlain as Higgins, Melissa Errico as Eliza and Paxton Whitehead as Pickering. Julian Holloway, son of Stanley Holloway, recreated his father's role of Alfred P. Doolittle. Donald Saddler was the choreographer.[16][29]

2001 London revival; 2003 Hollywood Bowl production

[edit]Cameron Mackintosh produced a new production on March 15, 2001, at the Royal National Theatre, which transferred to the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane on July 21. Directed by Trevor Nunn, with choreography by Matthew Bourne, the musical starred Martine McCutcheon as Eliza and Jonathan Pryce as Higgins, with Dennis Waterman as Alfred P. Doolittle. This revival won three Olivier Awards: Outstanding Musical Production, Best Actress in a Musical (Martine McCutcheon) and Best Theatre Choreographer (Matthew Bourne), with Anthony Ward receiving a nomination for Set Design.[30] In December 2001, Joanna Riding took over the role of Eliza, and in May 2002, Alex Jennings took over as Higgins, both winning Olivier Awards for Best Actor and Best Actress in a Musical respectively in 2003.[31] In March 2003, Anthony Andrews and Laura Michelle Kelly took over the roles until the show closed on August 30, 2003.[32]

A UK tour of this production began September 28, 2005. The production starred Amy Nuttall and Lisa O'Hare as Eliza, Christopher Cazenove as Henry Higgins, Russ Abbot and Gareth Hale as Doolittle, and Honor Blackman[33] and Hannah Gordon as Mrs. Higgins. The tour ended August 12, 2006.[34]

In 2003 a production of the musical at the Hollywood Bowl starred John Lithgow as Higgins, Melissa Errico as Eliza, Roger Daltrey as Doolittle, Kevin Earley as Freddy, Lauri Johnson as Mrs. Pearce, Caroline Blakiston as Mrs. Higgins, and Paxton Whitehead as Colonel Pickering.[35][36]

2018 Broadway and 2022 London revival

[edit]

A Broadway revival produced by Lincoln Center Theater and Nederlander Presentations Inc. began previews on March 15, 2018, at the Vivian Beaumont Theater and officially opened on April 19, 2018. It was directed by Bartlett Sher with choreography by Christopher Gattelli, scenic design by Michael Yeargan, costume design by Catherine Zuber and lighting design by Donald Holder.[37] The cast included Lauren Ambrose as Eliza, Harry Hadden-Paton as Professor Henry Higgins, Diana Rigg as Mrs. Higgins, Norbert Leo Butz as Alfred P. Doolittle, Allan Corduner as Colonel Pickering, Jordan Donica as Freddy, and Linda Mugleston as Mrs. Pearce.[38][39] Replacements included Rosemary Harris as Mrs. Higgins,[40] Laura Benanti as Eliza,[41] and Danny Burstein, then Alexander Gemignani, as Alfred P. Doolittle.[42] The revival closed on July 7, 2019, after 39 previews and 509 regular performances.[43] A North American tour of the production, starring Shereen Ahmed and Laird Mackintosh as Eliza and Higgins, opened in December 2019.[44] Performances were suspended in March 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and resumed in September 2021.[45] It is scheduled to run through August 2022.[46]

The production was presented by the English National Opera at the London Coliseum with performances from May 7, 2022, and an official opening on May 18, for a 16-week run until August 27. It starred Amara Okereke as Eliza, with Hadden-Paton reprising the role of Higgins, Stephen K. Amos as Alfred P. Doolittle, Vanessa Redgrave as Mrs. Higgins, Malcolm Sinclair as Colonel Pickering, Maureen Beattie as Mrs. Pearce and Sharif Afifi as Freddy.[47] Redgrave left the production early after contracting COVID-19.[48] A UK and Ireland tour began in September 2022 starring Michael Xavier as Higgins, Charlotte Kennedy as Eliza, Adam Woodyatt as Alfred P. Doolittle, John Middleton as Colonel Pickering, Lesley Garrett as Mrs Pearce and Tom Liggins as Freddy.[49]

Other major productions

[edit]Berlin, 1961

[edit]

A German translation of My Fair Lady opened on October 1, 1961, at the Theater des Westens in Berlin, starring Karin Hübner and Paul Hubschmid (and conducted, as was the Broadway opening, by Franz Allers). Coming at the height of Cold War tensions, just weeks after the closing of the East Berlin–West Berlin border and the erection of the Berlin Wall, this was the first staging of a Broadway musical in Berlin since World War II. As such it was seen as a symbol of West Berlin's cultural renaissance and resistance. Lost attendance from East Berlin (now no longer possible) was partly made up by a "musical air bridge" of flights bringing in patrons from West Germany, and the production was embraced by Berliners, running for two years.[50][51]

2007 New York Philharmonic concert and US tour

[edit]In 2007 the New York Philharmonic held a full-costume concert presentation of the musical. The concert had a four-day engagement lasting from March 7–10 at Lincoln Center's Avery Fisher Hall. It starred Kelsey Grammer as Higgins, Kelli O'Hara as Eliza, Charles Kimbrough as Pickering, and Brian Dennehy as Alfred Doolittle. Marni Nixon played Mrs. Higgins; Nixon had provided the singing voice of Audrey Hepburn in the film version.[52]

A U.S. tour of Mackintosh's 2001 West End production ran from September 12, 2007, to June 22, 2008.[53] The production starred Christopher Cazenove as Higgins, Lisa O'Hare as Eliza, Walter Charles as Pickering, Tim Jerome as Alfred Doolittle[54] and Nixon as Mrs. Higgins, replacing Sally Ann Howes.[55]

2008 Australian tour

[edit]An Australian tour produced by Opera Australia commenced in May 2008. The production starred Reg Livermore as Higgins, Taryn Fiebig as Eliza, Robert Grubb as Alfred Doolittle and Judi Connelli as Mrs Pearce. John Wood took the role of Alfred Doolittle in Queensland, and Richard E. Grant played the role of Henry Higgins at the Theatre Royal, Sydney.[56]

2010 Paris revival

[edit]A new production was staged by Robert Carsen at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris for a limited 27-performance run, opening December 9, 2010, and closing January 2, 2011. It was presented in English. The costumes were designed by Anthony Powell and the choreography was by Lynne Page. The cast was as follows: Sarah Gabriel / Christine Arand (Eliza Doolittle), Alex Jennings (Henry Higgins), Margaret Tyzack (Mrs. Higgins), Nicholas Le Prevost (Colonel Pickering), Donald Maxwell (Alfred Doolittle), and Jenny Galloway (Mrs. Pearce).[57]

2012 Sheffield production

[edit]A new production of My Fair Lady opened at Sheffield Crucible on December 13, 2012. Dominic West played Henry Higgins, and Carly Bawden played Eliza Doolittle. Sheffield Theatres' Artistic Director Daniel Evans was the director. The production ran until January 26, 2013.[58][59]

2016 Australian production

[edit]The Gordon Frost Organisation, together with Opera Australia, presented a production at the Sydney Opera House from August 30 to November 5, 2016. It was directed by Julie Andrews and featured the set and costume designs of the original 1956 production by Smith and Beaton.[60] The production sold more tickets than any other in the history of the Sydney Opera House.[61] The show's opening run in Sydney was so successful that in November 2016, ticket pre-sales were released for a re-run in Sydney, with the extra shows scheduled between August 24 and September 10, 2017, at the Capitol Theatre.[62] In 2017, the show toured to Brisbane from March 12 and Melbourne from May 11.[63]

The cast featured Alex Jennings as Higgins (Charles Edwards for Brisbane and Melbourne seasons), Anna O'Byrne as Eliza, Reg Livermore as Alfred P. Doolittle, Robyn Nevin as Mrs. Higgins (later Pamela Rabe), Mark Vincent as Freddy, Tony Llewellyn-Jones as Colonel Pickering, Deidre Rubenstein as Mrs. Pearce, and David Whitney as Karpathy.[62][63][64]

Critical reception

[edit]According to Geoffrey Block, "Opening night critics immediately recognized that My Fair Lady fully measured up to the Rodgers and Hammerstein model of an integrated musical ... Robert Coleman ... wrote 'The Lerner-Loewe songs are not only delightful, they advance the action as well. They are ever so much more than interpolations, or interruptions.'"[65] The musical opened to "unanimously glowing reviews, one of which said 'Don't bother reading this review now. You'd better sit right down and send for those tickets ...' Critics praised the thoughtful use of Shaw's original play, the brilliance of the lyrics, and Loewe's well-integrated score."[66]

A sampling of praise from critics, excerpted from a book form of the musical, published in 1956.[67]

- "My Fair Lady is wise, witty, and winning. In short, a miraculous musical." Walter Kerr, New York Herald Tribune.

- "A felicitous blend of intellect, wit, rhythm and high spirits. A masterpiece of musical comedy ... a terrific show." Robert Coleman, New York Daily Mirror.

- "Fine, handsome, melodious, witty and beautifully acted ... an exceptional show." George Jean Nathan, New York Journal American.

- "Everything about My Fair Lady is distinctive and distinguished." John Chapman, New York Daily News.

- "Wonderfully entertaining and extraordinarily welcomed ... meritorious in every department." Wolcott Gibbs, The New Yorker.

- "One of the 'loverliest' shows imaginable ... a work of theatre magic." John Beaufort, The Christian Science Monitor.

- "An irresistible hit." Variety.

- "One of the best musicals of the century." Brooks Atkinson, The New York Times.

The reception from Shavians was more mixed, however. Eric Bentley, for instance, called it "a terrible treatment of Mr. Shaw's play, [undermining] the basic idea [of the play]", even though he acknowledged it as "a delightful show".[68] My Fair Lady was later called "the perfect musical".[69]

Principal roles and casting history

[edit]Notable replacements

[edit]- Broadway (1956–1962)

- Eliza: Sally Ann Howes

- Higgins: Michael Allinson, Bramwell Fletcher, Tom Hellmore, Larry Keith, Edward Mulhare

- Pickering: Melville Cooper, Reginald Denny

- West End (1958–1963)

- Eliza: Anne Rogers

- Higgins: Alec Clunes, Charles Stapley

- Alfred P. Doolittle: James Hayter

- West End (2001–2003)

- Eliza: Joanna Riding, Laura Michelle Kelly

- Higgins: Alex Jennings, Anthony Andrews

- Freddy: Michael Xavier[49]

- Broadway revival (2018–2019)

- Eliza: Laura Benanti

- Alfred P. Doolittle: Danny Burstein, Alexander Gemignani

- Mrs. Higgins: Rosemary Harris

Awards and nominations

[edit]Original Broadway production

[edit]Sources: BroadwayWorld[82] TheatreWorldAwards[83]

| Year | Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1956 | Theatre World Award | Outstanding New York City Stage Debut Performance | John Michael King | Won |

| 1957 | Tony Award | Best Musical | Won | |

| Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Musical | Rex Harrison | Won | ||

| Best Performance by a Leading Actress in a Musical | Julie Andrews | Nominated | ||

| Best Performance by a Featured Actor in a Musical | Robert Coote | Nominated | ||

| Stanley Holloway | Nominated | |||

| Best Direction of a Musical | Moss Hart | Won | ||

| Best Choreography | Hanya Holm | Nominated | ||

| Best Scenic Design | Oliver Smith | Won | ||

| Best Costume Design | Cecil Beaton | Won | ||

| Best Conductor and Musical Director | Franz Allers | Won | ||

1976 Broadway revival

[edit]Sources: BroadwayWorld[84] Drama Desk[85]

| Year | Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | Tony Award | Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Musical | Ian Richardson | Nominated |

| George Rose | Won | |||

| Drama Desk Award | Outstanding Revival of a Musical | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Actor in a Musical | Ian Richardson | Won | ||

| Outstanding Featured Actor in a Musical | George Rose | Won | ||

| Outstanding Director of a Musical | Jerry Adler | Nominated | ||

1979 London revival

[edit]Source: Olivier Awards[86]

| Year | Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | Laurence Olivier Award | Best Actor in a Musical | Tony Britton | Nominated |

| Best Actress in a Musical | Liz Robertson | Nominated |

1981 Broadway revival

[edit]Source: BroadwayWorld[87]

| Year | Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | Tony Award | Best Revival | Nominated | |

1993 Broadway revival

[edit]Source: Drama Desk[88]

| Year | Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | Drama Desk Award | Outstanding Revival of a Musical | Nominated | |

| Outstanding Actress in a Musical | Melissa Errico | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Costume Design | Patricia Zipprodt | Nominated | ||

2001 London revival

[edit]Source: Olivier Awards[89]

| Year | Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Laurence Olivier Award | Outstanding Musical Production | Won | |

| Best Actor in a Musical | Jonathan Pryce | Nominated | ||

| Best Actress in a Musical | Martine McCutcheon | Won | ||

| Best Performance in a Supporting Role in a Musical | Nicholas Le Prevost | Nominated | ||

| Best Theatre Choreographer | Matthew Bourne | Won | ||

| Best Set Design | Anthony Ward | Nominated | ||

| Best Costume Design | Nominated | |||

| Best Lighting Design | David Hersey | Nominated | ||

| 2003 | Best Actor in a Musical | Alex Jennings | Won | |

| Best Actress in a Musical | Joanna Riding | Won | ||

2018 Broadway revival

[edit]| Year | Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Tony Award | Best Revival of a Musical | Nominated | |

| Best Actor in a Musical | Harry Hadden-Paton | Nominated | ||

| Best Actress in a Musical | Lauren Ambrose | Nominated | ||

| Best Featured Actor in a Musical | Norbert Leo Butz | Nominated | ||

| Best Featured Actress in a Musical | Diana Rigg | Nominated | ||

| Best Direction of a Musical | Bartlett Sher | Nominated | ||

| Best Choreography | Christopher Gattelli | Nominated | ||

| Best Scenic Design in a Musical | Michael Yeargan | Nominated | ||

| Best Lighting Design in a Musical | Donald Holder | Nominated | ||

| Best Costume Design in a Musical | Catherine Zuber | Won | ||

| Drama Desk Award | Outstanding Revival of a Musical | Won | ||

| Outstanding Actor in a Musical | Harry Hadden-Paton | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Featured Actress in a Musical | Diana Rigg | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Director of a Musical | Bartlett Sher | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Costume Design for a Musical | Catherine Zuber | Won | ||

| Drama League Award | Outstanding Revival of a Broadway or Off-Broadway Musical | Won | ||

| Distinguished Performance Award[90] | Lauren Ambrose | Nominated | ||

| Harry Hadden-Paton | Nominated | |||

| Outer Critics Circle Award | Outstanding Revival of a Musical | Won | ||

| Outstanding Actor in a Musical | Harry Hadden-Paton | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Actress in a Musical | Lauren Ambrose | Won | ||

| Outstanding Featured Actor in a Musical | Norbert Leo Butz | Won | ||

| Outstanding Director of a Musical | Bartlett Sher | Won[91] | ||

| Outstanding Choreography | Christopher Gattelli | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Set Design (Play or Musical) | Michael Yeagan | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Costume Design (Play or Musical) | Catherine Zuber | Won | ||

| Outstanding Sound Design (Play or Musical) | Marc Salzberg | Nominated | ||

| 2019 | Grammy Awards | Best Musical Theater Album | Nominated | |

Adaptations

[edit]1964 film

[edit]George Cukor directed the 1964 film adaptation, with Harrison returning in the role of Higgins. The casting of Audrey Hepburn as Eliza created controversy among theatregoers, both because Andrews was regarded as perfect in the part and because Hepburn's singing voice was dubbed (by Marni Nixon). Jack L. Warner, the head of Warner Bros., wanted "a star with a great deal of name recognition", but since Andrews did not have any film experience, he deemed success more likely with an established movie star.[92] (Andrews went on to star in Mary Poppins that same year for which she won both the Academy Award and the Golden Globe for Best Actress.) Lerner in particular disliked the film version of the musical, thinking it did not live up to the standards of Moss Hart's original direction. He was also unhappy with the casting of Hepburn as Eliza Doolittle and that the film was shot in its entirety at the Warner Bros. studio rather than, as he would have preferred, in London.[93] Despite the controversy, My Fair Lady was considered a major critical and box-office success, and won eight Oscars, including Best Picture of the Year, Best Actor for Rex Harrison, and Best Director for George Cukor.

Cancelled 2008 film

[edit]Columbia Pictures planned a new adaptation in 2008.[94] By 2011, John Madden had been signed to direct the film, and Emma Thompson had written a new screenplay, but the studio had shelved it by 2014.[95][96]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The original book of the musical, and original productions, placed the ball scene at the end of Act I. Some later productions have moved it to the beginning of Act II.

- ^ a b "'My Fair Lady' Synopsis, Cast, Scenes and Settings and Musical Numbers" guidetomusicaltheatre.com, accessed December 7, 2011.

- ^ Lerner, p. 36.

- ^ Lerner, p. 38.

- ^ Lerner, p. 39.

- ^ Lerner, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Lerner, p. 47.

- ^ Dominic, McHugh. Loverly: the life and times of My fair lady. Oxford University Press. pp. 20–48.

- ^ Morley, Sheridan. A Talent to Amuse: A Biography of Noël Coward, p. 369, Doubleday & Company, 1969.

- ^ "Extravagant Crowd: Mary Martin" Archived 2010-06-15 at the Wayback Machine, Beinecke Library, Yale University, accessed December 9, 2011.

- ^ "Dame Julie Andrews". Academy of Achievement. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Lawton, Jenny; Wernick, Adam (July 2014). "How Pygmalion went from feminist manifesto to chick flick". Retrieved November 5, 2022.

... the ending of the play was misinterpreted and altered in a way Shaw loathed.

- ^ David Leopold, "My Fair Lady: Pygmalion and beyond", The Al Hirschfeld Foundation

- ^ Lerner, p. 104.

- ^ Schreiber, Brad (May 2, 2017). Stop the show!: a history of insane incidents and absurd accidents in the theater. Hachette Books. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-0306902109.

- ^ a b c d Suskin, Steven. "My Fair Lady, 1956, 1976, and 1981", Show tunes: the songs, shows, and careers of Broadway's major composers (2010, 4th ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195125993, p. 224.

- ^ Vallance, Thomas. "Obituary: Edward Mulhare" The Independent (UK), May 27, 1997.

- ^ "A Fiery 'Fair Lady' Takes Over" Life, March 3, 1958, p. Front Cover, 51–54.

- ^ "'Fair Lady' Radiant $10,000,000". Variety. Vol. 213, no. 1. December 3, 1958. pp. 1, 92. Retrieved May 22, 2019 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "Billboard Albums, 'My Fair Lady'", AllMusic, accessed December 5, 2011.

- ^ "My Fair Lady Facts" Archived 2011-11-27 at the Wayback Machine, Myfairladythemusical.com, accessed December 5, 2011.

- ^ "Zena Dare" Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine, The-camerino-players.com, accessed December 5, 2011.

- ^ "International News", The Associated Press, October 26, 1979 ("Twenty-one years after Eliza Doolittle first straightened out her A's to the delight of Professor Higgins, "My Fair Lady" reopened in London Thursday night to rave notices.")

- ^ Borders, William. "A New Fair Lady Delights London Theatergoers", The New York Times, November 26, 1979, p. C15.

- ^ "'My Fair Lady', 1979", Phyllis.demon.co.uk, accessed December 7, 2011.

- ^ "0 Questions With...Liz Robertson", Whatsonstage.com, April 22, 2002.

- ^ "Olivier Winners 1979" Archived 2012-01-12 at the Wayback Machine, Olivierawards.com, accessed December 5, 2011.

- ^ Gussow, Mel (August 19, 1981). "The Stage: 'My Fair Lady' Returns", The New York Times, p. C17.

- ^ Simon, John (January 3, 1994). "This Lady Is For Burning" New York p. 63-64.

- ^ "Olivier Winners 2002" Archived 2012-01-12 at the Wayback Machine olivierawards.com, accessed December 5, 2011.

- ^ "Olivier Winners 2003" Archived 2012-01-12 at the Wayback Machine olivierawards.com, accessed December 5, 2011.

- ^ "'My Fair Lady', 2001–2003" Archived 2010-09-17 at the Wayback Machine, Albemarle-london.com, accessed December 5, 2011.

- ^ Langley, Sid (September 16, 2005). "Finding The Fair Lady Twice OVER", Birmingham Post, p. 13.

- ^ Bicknell, Gareth (July 21, 2006). "Gareth Hale is in My Fair Lady at Wales Millennium Centre from Tuesday, July 25 to Saturday, August 12". "Change of pace for versatile actor Hale", Liverpool Daily Post, p. 24.

- ^ Miller, Daryl H. (August 5, 2003). "This 'Fair Lady' is exceptional". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Gans, Andrew (May 19, 2003). "Rosemary Harris will play Mrs. Higgins in the upcoming Aug. 3 concert of My Fair Lady at the Hollywood Bowl". Playbill.

- ^ "First New Production of 'My Fair Lady' in 25 Years to 'Dance All Night' on Broadway Next Spring" Broadway World, March 6, 2017

- ^ McPhee, Ryan (October 5, 2017). "Broadway's New 'My Fair Lady' Finds Its Stars in Lauren Ambrose and Harry Hadden-Paton", Playbill.

- ^ Fierberg, Ruthie and Adam Hetrick (April 19, 2018). "Read Reviews for Broadway's Latest Revival of 'My Fair Lady', Starring Lauren Ambrose", Playbill.

- ^ Clement, Olivia (August 2, 2018). "Rosemary Harris to Join the Cast of Broadway's 'My Fair Lady'", Playbill.

- ^ Fierberg, Ruthie (August 23, 2018). "Laura Benanti Will Star as Eliza Doolittle in Broadway's 'My Fair Lady'", Playbill; and Fierberg, Ruthie (February 11, 2019). "Laura Benanti Extends Run in Broadway's 'My Fair Lady'", Playbill

- ^ McPhee, Ryan (October 16, 2018). "Danny Burstein to Join Broadway's My Fair Lady Revival", Playbill; and Fierberg, Ruthie (March 27, 2019). "Tony Nominee Alexander Gemignani to Join Broadway's My Fair Lady", Playbill

- ^ Fierberg, Ruthie. "My Fair Lady Revival Starring Laura Benanti Closes on Broadway July 7", Playbill, July 7, 2019

- ^ Robinson, Mark A. (July 9, 2019). "Lincoln Center Theater's My Fair Lady to Tour", Broadwaydirect.com; and Fierberg, Ruthie (December 18, 2019). "Take a Look at the North American Tour of My Fair Lady", Playbill

- ^ "Review Roundup: My Fair Lady" National Tour Resumes Performances; Read the Reviews!, November 10, 2021

- ^ "My Fair Lady", accessed November 10, 2021

- ^ Gans, Andrew. "Amara Okereke, Harry Hadden-Paton, Vanessa Redgrave Will Star in My Fair Lady at the London Coliseum", Playbill, February 25, 2022

- ^ Wood, Alex (August 5, 2022). "Vanessa Redgrave exits My Fair Lady in the West End". www.whatsonstage.com. Retrieved August 29, 2022.

- ^ a b Millward, Tom. "My Fair Lady UK and Ireland tour announces casting", WhatsOnStage.com, August 24, 2022

- ^ Müller, Peter E. (July 31, 2006). "Karin Hübner (1936–2006)". Die Welt. Retrieved February 11, 2017. (in German)

- ^ Von Birgit, Walter (October 22, 2011). "Theater des Westens Ein Million für diese Lady" [Theater of the West – A Million for This Lady]. Berliner Zeitung (in German). Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ Lawson, Kyle (June 10, 2008). "Marni Nixon in My Fair Lady" The Arizona Republic (Phoenix).

- ^ US Tour information Archived 2007-08-10 at the Wayback Machine MyFairLadyTheMusical.com

- ^ Tim Jerome bio Archived 2007-10-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gans, Andrew (August 28, 2007). "Marni Nixon to Join My Fair Lady Tour in Chicago" . Playbill.

- ^ "My Fair Lady". AusStage. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ My Fair Lady listing (in French), Chatelet-theatre.com, retrieved December 15, 2010; and Hetrick, Adam. "Show Boat, Sweeney Todd, and My Fair Lady to play Théâtre du Châtelet", Playbill, July 22, 2010

- ^ My Fair Lady sheffieldtheatres.co.uk

- ^ "Crucible's 'My Fair Lady', Starring Dominic West and Carly Bawden, Aiming for West End, May 2013?" broadwayworld.com, January 3, 2013.

- ^ Spring, Alexandra (August 4, 2015). "Julie Andrews to direct Sydney Opera House production of 'My Fair Lady'" The Guardian (London).

- ^ Boyd, Edward (October 6, 2016). "'My Fair Lady' musical by Julie Andrews sold more tickets than any other production in history", The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ a b "My Fair Lady: Capitol Theatre, Sydney", Opera Australia, accessed 1 July 2019

- ^ a b "My Fair Lady: Regent Theatre, Melbourne", Opera Australia, accessed 1 July 2019

- ^ "My Fair Lady: Sydney Opera House", Opera Australia, accessed 1 July 2019

- ^ Block, Geoffrey (2004). Enchanted Evenings: The Broadway Musical from Show Boat to Sondheim. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0195167306.

- ^ Everett, William A.; Paul R. Laird (May 22, 2008). The Cambridge Companion to the Musical (Second ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0521862387. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ My Fair Lady: A Musical Play in Two Acts. Based on Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw. Adaptation and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner, Music by Frederick Loewe. New York: Doward-McCann, Inc., 1956.

- ^ Video on YouTube

- ^ Steyn, Mark (2000). Broadway Babies Say Goodnight. ISBN 9780415922876. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ "My Fair Lady: Mark Hellinger Theatre". Internet Broadway Database.

- ^ "My Fair Lady West End Cast". Broadway World.

- ^ "My Fair Lady: St. James Theatre". Internet Broadway Database.

- ^ McHugh, Dominic (2014). Loverly: The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 187. ISBN 9780199381005.

- ^ "My Fair Lady: Uris Theatre". Internet Broadway Database.

- ^ "My Fair Lady: Virginia Theatre". Internet Broadway Database.

- ^ "My Fair Lady West End Revival Cast". Broadway World.

- ^ "Who's Who". Lincoln Center Theater.

- ^ "Cast complete for London Coliseum My Fair Lady". Playbill.

- ^ Barnes, Peter (August 4, 2002). "Obituary: Peter Bayliss". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Following Onstage Collapse, Peter Land Departs RUTHLESS! Off-Broadway". Broadway World. July 30, 2015.

...the Alan Jay Lerner-directed My Fair Lady (Freddy Eynsford-Hill)...

- ^ "Betty Paul: Stage and screen actress and writer of ITV's first rural soap opera". The Independent. London. April 12, 2011. Archived from the original on 2022-06-18.

Paul returned to acting for a two-year run in the West End as Mrs Pearce, the housekeeper, in My Fair Lady (1979–81).

- ^ "Tony Awards, 1957", Broadwayworld.com, accessed December 6, 2011.

- ^ "Previous Theatre World Award Recipients, 1955–56", Theatreworldawards.org, accessed December 6, 2011.

- ^ "Tony Awards, 1976", Broadwayworld.com, accessed December 6, 2011.

- ^ "1975–1976 22nd Drama Desk Awards", Dramadesk.com, accessed December 6, 2011.

- ^ "Olivier Winners 1979" Archived 2012-01-12 at the Wayback Machine olivierawards.com, accessed December 6, 2011.

- ^ "Tony Awards, 1982" Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine, Broadwayworld.com, accessed December 6, 2011.

- ^ "1993–1994 40th Drama Desk Awards", Dramadesk.com, accessed December 6, 2011.

- ^ "Olivier Winners 2002" Archived 2012-01-12 at the Wayback Machine olivierawards.com, accessed December 6, 2011.

- ^ Norbert Leo Butz was ineligible for this award for his performance as Alfred Doolittle, as he had already won the award in a previous year

- ^ Tied with Tina Landau for SpongeBob SquarePants

- ^ Roman, James W. "My Fair Lady" Bigger Than Blockbusters: Movies That Defined America, ABC-CLIO, 2009, ISBN 0-313-33995-3, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Lerner, The Street Where I Live pp 134–6.

- ^ Gans, Andrew (June 2, 2008). "Columbia Pictures and CBS Films to Develop New My Fair Lady Film". Playbill. Archived from the original on 2008-06-07. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- ^ Lyttelton, Oliver (February 18, 2011). "Colin Firth Again Being Pursued For 'My Fair Lady' Remake; Carey Mulligan Still Attached". IndieWire. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ "Cameron Mackintosh Says Film Remake of My Fair Lady Has Been Shelved". Playbill. Archived from the original on 2014-05-06. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

References

[edit]- Citron, David (1995). The Wordsmiths: Oscar Hammerstein 2nd and Alan Jay Lerner, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508386-5

- Garebian, Keith (1998). The Making of My Fair Lady, Mosaic Press. ISBN 0-88962-653-7

- Green, Benny, Editor (1987). A Hymn to Him : The Lyrics of Alan Jay Lerner, Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 0-87910-109-1

- Jablonski, Edward (1996). Alan Jay Lerner: A Biography, Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 0-8050-4076-5

- Lees, Gene (2005). The Musical Worlds of Lerner and Loewe, Bison Books. ISBN 0-8032-8040-8

- Lerner, Alan Jay (1985). The Street Where I Live, Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80602-9

- McHugh, Dominic. Loverly: The Life and Times of "My Fair Lady" (Oxford University Press; 2012) 265 pages; uses unpublished documents to study the five-year process of the original production.

- Shapiro, Doris (1989). We Danced All Night: My Life Behind the Scenes With Alan Jay Lerner, Barricade Books. ISBN 0-942637-98-4

External links

[edit]- 1956 musicals

- American plays adapted into films

- Broadway musicals

- West End musicals

- Musicals based on plays

- Laurence Olivier Award–winning musicals

- Tony Award for Best Musical

- Musicals by Alan Jay Lerner

- Musicals by Frederick Loewe

- Musicals set in the 1900s

- Musicals set in England

- Tony Award–winning musicals

- Musicals set in London

- Works based on Pygmalion (play)