Boston Marathon bombing

| Boston Marathon bombing | |

|---|---|

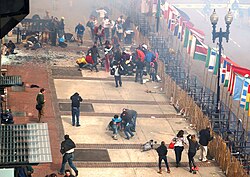

Moments after the first explosion | |

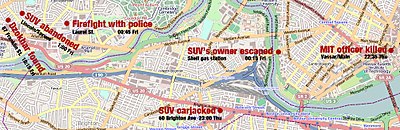

Bomb locations/marathon route | |

| Location | Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Date | April 15, 2013 2:49 p.m. (EDT) |

Attack type | Bombings, domestic terrorism[1] |

| Weapons | Two pressure cooker bombs |

| Deaths | 6 total:

|

| Injured | 281 |

| Victims |

|

| Perpetrators | |

| Motive | Revenge for American military action in Iraq and Afghanistan[2][3] |

The Boston Marathon bombing, sometimes referred to as simply the Boston bombing,[4] was an Islamist domestic terrorist attack that took place during the 117th annual Boston Marathon on April 15, 2013. Brothers Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev planted two homemade pressure cooker bombs that detonated near the finish line of the race 14 seconds and 210 yards (190 m) apart. Three people were killed and hundreds injured, including 17 who lost limbs.[1][5][6]

On April 18, 2013, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) released images of two suspects in the bombing.[7][8][9] The two suspects were later identified as the Tsarnaev brothers. Later on the evening of April 18, the Tsarnaev brothers killed an MIT policeman (Sean Collier) and proceeded to commit a carjacking. They engaged in a shootout with police in nearby Watertown, during which two officers were severely injured (one of the injured officers, Dennis Simmonds, died a year later). Tamerlan was shot several times, and his brother Dzhokhar ran him over while escaping in the stolen car. Tamerlan died soon thereafter.

An unprecedented search for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev ensued, with thousands of law enforcement officers searching a 20-block area of Watertown.[10] Residents of Watertown and surrounding communities were asked to stay indoors, and the transportation system and most businesses and public places closed.[11][12] After a Watertown resident discovered Dzhokhar hiding in a boat in his backyard,[13] Tsarnaev was shot and wounded by police before being taken into custody on the evening of April 19.[14][15]

During questioning, Dzhokhar said that he and his brother were motivated by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, that they were self-radicalized and unconnected to any outside terrorist groups, and that he was following his brother's lead. He said they learned to build explosive devices from the online magazine of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.[16] He also said they had intended to travel to New York City to bomb Times Square. He was convicted of 30 charges, including use of a weapon of mass destruction and malicious destruction of property resulting in death.[17][18][19]

Two months later, he was sentenced to death,[20] but the sentence was vacated by the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit.[21] A writ of certiorari was granted by the Supreme Court of the United States, which considered the questions of whether the lower court erred in vacating the death sentence. After hearing arguments as United States v. Tsarnaev, the Court upheld the death penalty, reversing the First Circuit Court's decision.[22][23]

Bombing

[edit]

The 117th annual Boston Marathon was run on Patriots' Day, April 15, 2013. At 2:49 p.m. EDT (18:49 UTC), two bombs detonated about 210 yards (190 m) apart at the finish line on Boylston Street near Copley Square.[24][25][26][27] The first exploded outside Marathon Sports at 671–673 Boylston Street at 2:49:43 p.m.[24] At the time of the first explosion, the race clock at the finish line showed 04:09:43[28]—the elapsed time since the Wave 3 start at 10:40 a.m. The second bomb exploded at 2:49:57 p.m.,[25][29] 14 seconds later and one block farther west at 755 Boylston Street.[6] The explosions took place nearly three hours after the winning runner crossed the finish line,[29] but with more than 5,700 runners yet to finish.[30]

Windows on adjacent buildings were blown out, but there was no structural damage.[29][31] Runners continued to cross the line until 2:57 p.m.[32]

Casualties and initial response

[edit]Rescue workers and medical personnel, on hand as usual for the marathon, gave aid as additional police, fire, and medical units were dispatched,[33][34] including from surrounding cities as well as private ambulances from all over the state. The explosions killed three civilians and injured 264 others.[5][35]

Police, following emergency plans, diverted all remaining runners to Boston Common and Kenmore Square. The nearby Lenox Hotel and other buildings surrounding the scene were evacuated.[27] Immediately after the bombing occurred and medically injured people were transported, the police closed a 15-block area around the blast site; this was reduced to a 12-block crime scene the next day.[27][31][36] Boston police commissioner Edward F. Davis recommended that people stay off the streets.[31]

Dropped bags and packages, abandoned as their owners fled from the blasts, increased uncertainty as to the possible presence of more bombs[24][37] and many false reports were received.[7][27][38] Simultaneously an electrical fire at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in nearby Dorchester was initially feared to be a bomb.[39]

The airspace over Boston was restricted, and departures halted from Boston's Logan International Airport.[40] Some local transit service was halted as well.[29]

The Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency suggested that people trying to contact those in the vicinity use text messaging instead of voice calls because of the crowded cell phone lines.[29] Cell phone service in Boston was congested but remained in operation, despite some media reports stating that cell service was shut down to prevent cell phones from being used as detonators.[41]

The American Red Cross helped concerned friends and family receive information about runners and casualties.[42][43] The Boston Police Department also set up a call helpline for people concerned about relatives or acquaintances to contact and a line for people to provide information.[44] Google Person Finder activated their disaster service under Boston Marathon Explosions to log known information about missing people as a publicly viewable file.[45]

Due to the closure of several hotels near the blast zone, a number of visitors were left with nowhere to stay; many Boston-area residents opened their homes to them.[46]

Initial investigation

[edit]

The Federal Bureau of Investigation led the investigation, assisted by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Counterterrorism Center, and the Drug Enforcement Administration.[47] It was initially believed by some that North Korea was behind the attack.[48][49]

United States government officials stated that no intelligence reports suggested such an attack. Representative Peter King, a member of the House Intelligence Committee, said: "I received two top secret briefings last week on the current threat levels in the United States, and there was no evidence of this at all."[50]

Evidence found near the blast sites included bits of metal, nails, ball bearings,[51] black nylon pieces from a backpack,[52] remains of an electronic circuit board and wiring.[51][53] A pressure cooker lid was found on a nearby rooftop.[54] Both of the improvised explosive devices were pressure cooker bombs manufactured by the bombers.[55][56][57] Authorities confirmed that the brothers used bomb-making instructions found in Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula's Inspire magazine.[58][59] After the suspects were identified, The Boston Globe reported that Tamerlan purchased fireworks from a fireworks store in New Hampshire.[60]

April 18–19 shootings and search

[edit]| Tsarnaev brothers shootings and search | |

|---|---|

Security camera images of Tamerlan Tsarnaev (front) and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev just prior to the bombings[61] | |

| Location | Shooting: Corner of Vassar Street and Main Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts[62] Firefight and manhunt: Watertown, Massachusetts |

| Date | Shooting: April 18, 2013, 10:25 p.m. Firefight and manhunt: April 19, 2013, 12:30 a.m. – 8:42 p.m. |

Attack type | Shooting, vehicle ramming, lone wolf terrorism[63]

|

| Weapons |

|

| Deaths | 3 (including Tamerlan Tsarnaev and a victim who died in 2014[64]) |

| Injured | 16 (via gunfire) |

| Perpetrators |

|

| Motive | Firearms theft (murder of MIT officer) Evading arrest (Watertown shootout) |

Release of suspect photos

[edit]Jeff Bauman was immediately adjacent to one of the bombs and lost both legs; he wrote while in the hospital: "Bag, saw the guy, looked right at me".[65] He later gave a detailed description of the suspects, which enabled images of them to be identified and circulated quickly.[65][66][67]

At 5:00 p.m. on April 18, three days after the bombing, the FBI released images of two suspects carrying backpacks, asking the public's help in identifying them.[68][69] The FBI said that they were doing this in part to limit harm to people wrongly identified by news reports and on social media.[70] As seen on video, the suspects stayed to observe the chaos after the explosions, then walked away casually. The public sent authorities a deluge of photographs and videos.[69] The FBI-released images depicted Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev.[71]

MIT shooting and carjacking

[edit]

Hours after the FBI released photos of the two suspects in the bombing, Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev visited their family's apartment in Cambridge. There, they obtained five improvised explosive devices (IEDs), ammunition, a semiautomatic handgun, and a machete. The two brothers then drove to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[15]

On April 18, 2013 at 10:25 p.m., the Tsarnaev brothers ambushed and shot Sean A. Collier of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Police Department six times.[72][15] The two brothers were attempting to steal Collier's Smith & Wesson M&P45 sidearm, which they could not free from his holster because of its security retention system.[73] Collier, aged 27, was seated in his police car near Building 32 on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology campus.[14][74] He died shortly after the shooting.[14][75]

The brothers then carjacked a Mercedes-Benz M-Class SUV in the Allston-Brighton neighborhood of Boston. Tamerlan took the owner, Chinese national Dun "Danny" Meng[76] (Chinese: 孟盾),[77] hostage and told him that he was responsible for the Boston bombing and for shooting Collier.[14] Dzhokhar followed them in their green Honda Civic, later joining them in the Mercedes-Benz. Interrogation later revealed that the brothers "decided spontaneously" that they wanted to go to New York and bomb Times Square.[78]

The Tsarnaev brothers forced Meng to use his ATM cards to obtain $800 in cash (equivalent to $1,046 in 2023).[79][80] They transferred objects to the Mercedes-Benz and one brother followed it in their Civic,[81] for which an all-points bulletin was issued. The Tsarnaev brothers then drove to a Shell gas station on Memorial Drive in Cambridge to fill up for the long drive to Times Square. While Dzhokhar went inside the Shell station to pay for food, Meng, fearing that the suspects would harm him during the drive, escaped from the Mercedes and ran across the street to a Mobil gas station, asking the clerk to call 911.[82][83] His cell phone remained in the vehicle, allowing the police to focus their search on Watertown.[84]

Watertown shootout

[edit]Shortly after midnight on April 19, Watertown police officer Joseph Reynolds identified the brothers in the Honda and the stolen Mercedes after overhearing radio traffic that the vehicle was "pinged" by Cambridge officers on Dexter Avenue in Watertown. Reynolds followed the vehicle while waiting for additional units to perform a high-risk traffic stop when the suspect vehicles both turned onto Laurel Street and stopped at the intersection of Laurel and Dexter.[citation needed]

Tamerlan Tsarnaev stepped out of the Mercedes and immediately opened fire on Officer Reynolds and Sergeant John MacLellan, who both returned fire and requested emergency assistance over their radios. A gun battle ensued between Tsarnaev, the aforementioned officers, and additional officers responding to the "shots fired" radio transmissions from Reynolds and MacLellan in the 100 block of Laurel St.[14][85][86] An estimated 200 to 300 shots were fired. The suspects shot 56 times, detonated at least one pressure cooker bomb, and threw five "crude grenades", three of which exploded.[86][87]

The agencies involved in the nearly seven-minute shootout included the Watertown Police Department, Cambridge Police Department, Boston Police Department, Massachusetts State Police (MSP), Boston University Police Department, and MBTA Transit Police Department. Most of the officers involved were equipped by their respective agencies with either the Glock 22 or Glock 23 .40 S&W-caliber pistols. MSP troopers were armed with Smith & Wesson M&P45 pistols chambered in .45 ACP; this led investigators to match the 9mm casings and projectiles found at the scene to the suspects' 9mm Ruger P95 pistol.

According to Watertown Police Chief Edward Deveau, the brothers had an "arsenal of guns".[88] Tamerlan eventually ran out of ammunition and threw his empty Ruger pistol at Watertown PD Sergeant Jeffrey Pugliese, who subsequently tackled him with assistance from Sergeant MacLellan.[89][90]

Tamerlan's younger brother Dzhokhar then drove the stolen SUV toward Tamerlan and the police, who unsuccessfully tried to drag Tamerlan out of the car's path and handcuff him;[89][90] the car ran over Tamerlan and dragged him a short distance down the street, narrowly missing the Watertown officers. Watertown Sgt. MacLellan later stated that the younger brother had thought they were doing CPR on another officer and tried to run them over.[14][89][91][92] Dzhokhar abandoned the car half a mile away and fled on foot.[14][84][93][94] Badly wounded, Tamerlan Tsarnaev was taken into custody and died at 1:35 a.m. at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.[95]

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority Police Officer Richard H. Donohue Jr.[96] was critically wounded in the leg[97] in crossfire from other officers shooting at the fleeing vehicle, but survived. Reports revealed that his gunshot wound severed his femoral artery, and he nearly died. Fast-acting efforts by his fellow officers and medical personnel saved his life.[98] Boston Police Department officer Dennis Simmonds was injured by a hand grenade and died on April 10, 2014.[64] Fifteen other officers were also injured.[85] A later report by Harvard Kennedy School's Program on Crisis Leadership concluded that lack of coordination among police agencies had put the public at excessive risk during the shootout.[99]

Only one firearm, Tsarnaev's Ruger P95, was recovered at the scene. That firearm was found to have a defaced serial number.[100][101]

Further investigation and post-shootout search for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev

[edit]Records on the Honda left at the Watertown shootout scene identified the bombers[102] Tamerlan and Dzhokhar "Jahar" Tsarnaev.[103][104] The FBI released additional photos of the two during the Watertown incident.[105] Early on April 19, investigators released the name and photo of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev to the public.[15] In addition, Watertown residents received automated calls asking them to stay indoors.[106] That same morning Governor Patrick asked residents of Watertown and adjacent cities and towns[107][108][109] to "shelter in place".[110] Somerville residents also received automated calls instructing them to shelter in place.[111]

A 20-block area of Watertown was cordoned off, and residents were told not to leave their homes or answer the door as officers scoured the area in tactical gear. Helicopters circled the area and SWAT teams in armored vehicles moved through in formation, with officers going door to door and searching houses.[112] These actions generated discussions about the legality of searching large numbers of houses without a search warrant, with The Atlantic stating that this kind of search is legal due to exigent circumstances.[113] Agencies on the scene were the FBI; the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives; Diplomatic Security Service; HSI-ICE; the National Guard; the Boston, Cambridge, and Watertown Police departments; and the Massachusetts State Police. The show of force was the first major field test of the interagency task forces created in the wake of the September 11 attacks.[114]

The entire public transit network and most Boston taxi services[a] were suspended, as was Amtrak service to and from Boston.[74][116] Logan International Airport remained open under heightened security.[116] Universities, schools, businesses, and other facilities were closed as thousands of law enforcement personnel participated in the door-to-door search in Watertown. Others followed up on other leads, including searching the house that the brothers shared in Cambridge, where seven improvised explosive devices were found.[117]

The brothers' father spoke from his home in Makhachkala, Dagestan, encouraging Dzhokhar to: "Give up. You have a bright future ahead of you. Come home to Russia." He continued, "If they killed him, then all hell would break loose."[118] On television, Dzhokhar's uncle from Montgomery Village, Maryland, pleaded with him to turn himself in.[119]

Also on April 19, the FBI, West New York Police Department, and Hudson County Sheriff's Department seized computer equipment from the apartment of the Tsarnaevs' sister in West New York, New Jersey.[120]

On the evening of April 19, after the shelter-in-place order had been lifted, David Henneberry, a Watertown resident outside the search area, noticed that the tarpaulin was loose on his parked boat.[121][122] Investigating, he saw a body lying inside the boat in a pool of blood.[123] He contacted the authorities at 6:42 p.m., and they surrounded the boat. A police helicopter verified movement through a thermal imaging device.[85] The figure inside started poking at the tarpaulin, prompting police to shoot at the boat.[124]

According to Boston Police Commissioner Ed Davis and Watertown Police Chief Deveau, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was shooting at police from inside the boat, "exchanging fire for an hour".[125] A subsequent report indicated that the firing lasted for a shorter time.[126] Despite this, Tsarnaev was found to have no weapon when he was captured.[126]

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was arrested at 8:42 p.m.[127][128] and taken to Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, where he was listed in critical condition[129] with gunshot wounds to the head, neck, legs, and hand.[130] Initial reports that the neck wound represented a suicide attempt were contradicted by Tsarnaev's being found unarmed.[131] The situation was chaotic, according to a police source quoted by The Washington Post, and the firing of weapons occurred during "the fog of war".[126] A subsequent review by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts provided this more specific summary: "One officer fired his weapon without appropriate authority in response to perceived movement in the boat, and surrounding officers followed suit in a round of 'contagious fire', assuming Tsarnaev was firing on them. Weapons continued to be fired for several seconds until on-scene supervisors ordered a ceasefire and regained control of the scene. The unauthorized shots created another dangerous crossfire situation".[132] The confusion was caused in part by a lack of clearly identified and coordinated law enforcement command of the thousands of officers from surrounding communities who self-deployed into the Watertown area during the events.[133]

After Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was taken into custody, the FBI revealed that it had investigated Tamerlan Tsarnaev in 2011 after the FSB, the Russian intelligence agency, had expressed concern about his potential radicalization. That investigation included an interview with Tamerlan Tsarnaev. At that time, the FBI found no evidence of terrorist involvement by Tamerlan Tsarnaev.[134][135][136]

On April 24, investigators reported that they had reconstructed the bombs, and believed that they had been triggered by remote controls used for toy cars.[137]

Legal proceedings

[edit]Interrogation

[edit]United States Senators Kelly Ayotte, Saxby Chambliss, Lindsey Graham, and John McCain, and Representative Peter T. King suggested that Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, a U.S. citizen, should be tried as an unlawful enemy combatant rather than as a criminal, potentially preventing him from obtaining legal counsel.[138][139] Others said that doing so would be illegal, including prominent American legal scholar and lawyer Alan Dershowitz, and would jeopardize the prosecution.[140][141] The government decided to try Dzhokhar in the federal criminal court system and not as an enemy combatant.[142]

Dzhokhar was questioned for 16 hours by investigators but stopped communicating with them on the night of April 22 after Judge Marianne Bowler read him a Miranda warning.[78][143] Dzhokhar had not previously been given a Miranda warning, as federal law enforcement officials invoked the warning's public safety exception.[144] This raised doubts whether his statements during this investigation would be admissible as evidence and led to a debate surrounding Miranda rights.[145][146][147]

Charges and detention

[edit]

On April 22, 2013, formal criminal charges were brought against Tsarnaev in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts during a bedside hearing while he was hospitalized. He was charged with use of a weapon of mass destruction and with malicious destruction of property resulting in death.[17] Some of the charges carried potential sentences of life imprisonment or the death penalty.[148] Tsarnaev was judged to be awake, mentally competent, and lucid, and he responded to most questions by nodding. The judge asked him whether he was able to afford an attorney and he said no; he was represented by the Federal Public Defender's office.[149] On April 26, Dzhohkar Tsarnaev was moved from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center to the Federal Medical Center at Fort Devens, about 40 miles (64 km) from Boston. FMC Devens is a federal prison medical facility at a former Army base[150] where he was held in solitary confinement at a segregated housing unit[151] with 23-hour-per-day lockdown.[152]

On July 10, 2013, Tsarnaev pleaded not guilty to 30 charges in his first public court appearance, including a murder charge for MIT police officer Sean Collier.[153] He was back in court for a status hearing on September 23,[154] and his lawyers requested more time to prepare their defense.[155] On October 2, Tsarnaev's attorneys asked the court to lift the special administrative measures (SAMs) imposed by Attorney General Holder in August, saying that the measures had left Tsarnaev unduly isolated from communication with his family and lawyers, and that no evidence suggested that he posed a future threat.[156]

Trial and sentencing

[edit]Jury selection began on January 5, 2015, and was completed on March 3, with a jury consisting of eight men and ten women (including six alternates).[157] The trial began on March 4 with Assistant U.S. Attorney William Weinreb describing the bombing and painting Dzhokhar as "a soldier in a holy war against Americans" whose motive was "reaching paradise". He called the brothers equal participants.[158]

Defense attorney Judy Clarke admitted that Dzhokhar Tsarnaev had placed the second bomb and was present at the murder of Sean Collier, the carjacking of Dun Meng, and the Watertown shootout, but she emphasized the influence that his older brother had on him, portraying him as a follower.[159] Between March 4 and 30, prosecutors called more than 90 witnesses, including bombing survivors who described losing limbs in the attack, and the government rested its case on March 30.[160] The defense rested as well on March 31, after calling four witnesses.[161]

Tsarnaev was found guilty on all 30 counts on April 8.[162] The sentencing phase of the trial began on April 21,[163] and a further verdict was reached on May 15 in which it was recommended that he be put to death.[164] Tsarnaev was sentenced to death on June 24, after apologizing to the victims.[165] In 2018, Tsarnaev's lawyers appealed on the grounds that a lower-court judge's refusal to move the case to another city not traumatized by the bombings deprived him of a fair trial.[166]

On July 30, 2020, Tsarnaev's death sentence was reversed by the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, which found that, during jury selection, the District Court did not properly screen prospective jurors on how much they had heard of the case. The First Circuit vacated the death sentence and three of the other thirty convictions against Tsarnaev, and ordered a new penalty phase jury trial with fresh jurors, leaving the decision of a new change of venue to the District Court. Tsarnaev's remaining convictions still carried multiple life sentences, ensuring that he would remain in prison regardless of the results of the new trial.[21] The United States government appealed this ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court, which granted certiorari in the case United States v. Tsarnaev in March 2021, which was argued before the Court on October 13, 2021.[23] On March 4, 2022, the Supreme Court reversed the decision of the First Circuit and reinstated Tsarnaev's death penalty.[167][35]

Motives and backgrounds of the Tsarnaev brothers

[edit]Motives

[edit]According to FBI interrogators, Dzhokhar and his brother were motivated by extremist beliefs but "were not connected to any known terrorist groups", instead learning to build explosive weapons from an online magazine published by al-Qaeda affiliates in Yemen.[16] They further alleged that "Dzhokhar and his brother considered suicide attacks and striking the Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular on the Fourth of July";[168] but ultimately decided to use remotely-activated pressure cooker bombs and other IEDs. Fox News reported that the brothers "chose the prestigious race as a 'target of opportunity' ... [after] the building of the bombs came together more quickly than expected".[169][170]

Dzhokhar said that he and his brother wanted to defend Islam from the U.S., accusing the U.S. of conducting the Iraq War and War in Afghanistan against Muslims.[142][171][172] A CBS report revealed that Dzhokhar had scrawled a note with a marker on the interior wall of the boat where he was hiding; the note stated that the bombings were "retribution for U.S. military action in Afghanistan and Iraq", and called the Boston victims "collateral damage", "in the same way innocent victims have been collateral damage in U.S. wars around the world".[3] Photographs of the note were later used in the trial.[173][174]

Some political science and public policy writers theorize that the primary motives might have been sympathy towards the political aspirations in the Caucasus region and Tamerlan's inability to become fully integrated into American society.[175] According to the Los Angeles Times, a law enforcement official said that Dzhokhar "did not seem as bothered about America's role in the Muslim world" as his brother Tamerlan had been.[59] Dzhokhar identified Tamerlan as the "driving force" behind the bombing, and said that his brother had only recently recruited him to help.[142][176]

Some journalists and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev's defense attorney have suggested that the FBI may have recruited or attempted to recruit Tamerlan Tsarnaev as an informant.[177][178][179][180]

Backgrounds

[edit]

Tamerlan Tsarnaev was born in 1986 in the Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, North Caucasus.[181] Dzhokhar was born in 1993 in Kyrgyzstan, although some reports say that his family claims that he was born in Dagestan.[182] The family spent time in Tokmok, Kyrgyzstan, and in Makhachkala, Dagestan.[80][183] They are half Chechen through their father Anzor, and half Avar[184] through their mother Zubeidat. They never lived in Chechnya, yet the brothers identified themselves as Chechen.[182][185][186][187]

The Tsarnaev family immigrated to the United States in 2002[14][185][188][189] where they applied for political asylum, settling in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[104] Tamerlan Tsarnaev attended Bunker Hill Community College but dropped out to become a boxer. His goal was to gain a place on the U.S. Olympic boxing team, saying that, "unless his native Chechnya becomes independent", he would "rather compete for the United States than for Russia".[190][191] He married U.S. citizen Katherine Russell on July 15, 2010, in the Masjid Al Quran Mosque. While initially quoted in a student magazine as saying, "I don't have a single American friend. I don't understand them," a later FBI interview report documents Tamerlan stating it was a misquote, and that most of his friends were American.[192][193] He had a history of violence, including an arrest in July 2009 for assaulting his girlfriend.[194]

The brothers were Muslim; Tamerlan's aunt stated that he had recently become a devout Muslim.[186][187] Tamerlan became more devout and religious after 2009,[195][196] and a YouTube channel in his name was linked to Salafist[195] and Islamist[197][198] videos. The FBI was informed by the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) in 2011 that he was a "follower of radical Islam".[197] In response, the FBI interviewed Tamerlan and his family and searched databases, but they did not find any evidence of "terrorism activity, domestic or foreign".[199][200][201][202][203][204] During the 2012 trip to Dagestan, Tamerlan was reportedly a frequent visitor at a mosque on Kotrova Street in Makhachkala,[205][206][207] believed by the FSB to be linked with radical Islam.[206] Some believe that "they were motivated by their faith, apparently an anti-American, radical version of Islam" acquired in the U.S.,[208] while others believe that the turn happened in Dagestan.[209]

At the time of the bombing, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was a student at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth with a major in marine biology.[210] He became a naturalized U.S. citizen on September 11, 2012.[211] Tamerlan's boxing coach reported to NBC that the young brother was greatly affected by Tamerlan and admired him.[212][213]

Tamerlan was previously connected to the triple homicide in Waltham, Massachusetts, on the evening of September 11, 2011, but he was not a suspect at the time.[214][215] Brendan Mess, Erik Weissman, and Raphael Teken were murdered in Mess's apartment. All had their throats slit from ear to ear with such great force that they were nearly decapitated. The local district attorney said that it appeared that the killer and the victims knew each other, and that the murders were not random.[216] Tamerlan Tsarnaev had previously described murder victim Brendan Mess as his "best friend".[217] After the bombing and subsequent revelations of Tsarnaev's personal life, the Waltham murders case was reexamined in April 2013 with Tsarnaev as a new suspect.[214] Both ABC and The New York Times have reported that there is strong evidence which implicates Tsarnaev in this triple homicide.[217][218]

Some analysts claim that the Tsarnaevs' mother Zubeidat Tsarnaeva is a radical extremist and supporter of jihad who influenced her sons' behavior.[219][220] This prompted the Russian government to warn the U.S. government on two occasions about the family's behavior. Both Tamerlan and his mother were placed on a terrorism watch list about 18 months before the bombing took place.[221]

Other arrests, detentions, and prosecutions

[edit]People detained and released

[edit]On April 15, several people who were near the scene of the blast were taken into custody and questioned about the bombing, including a Saudi man whom police stopped as he was walking away from the explosion; they detained him when some of his responses made them uncomfortable.[222][223][224][225] Law enforcement searched his residence in a Boston suburb, and the man was found to have no connection to the attack. An unnamed U.S. official said, "he was just at the wrong place at the wrong time".[226][227][228]

On the night of April 18, two men who were riding in a taxi in the vicinity of the shootout were arrested and released shortly after that when police determined that they were not involved in the Marathon attacks.[229] Another man was arrested several blocks from the site of the shootout and was forced to strip naked by police who feared that he might have concealed explosives. He was released that evening after a brief investigation determined that he was an innocent bystander.[230][231]

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev's roommates

[edit]Personal backgrounds

[edit]Robel Phillipos, 19, was a U.S. citizen of Ethiopian descent living in Cambridge who was arrested and faced with charges of knowingly making false statements to police.[232][233] He graduated from high school in 2011 with Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.[234] Dias Kadyrbayev, 19, and Azamat Tazhayakov, 20, were natives of Kazakhstan living in the U.S.[235][236] They were Dzhokhar Tsarnaev's roommates in an off-campus housing complex in New Bedford, Massachusetts, where Tsarnaev had sometimes stayed.[232]

Phillipos, Kadyrbayev, Tazhayakov, and Tsarnaev entered the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth in the fall of 2011 and knew each other well. After seeing photos of Tsarnaev on television, they traveled to his dorm room, where Kadyrbayev and Tazhayakov retrieved a backpack and laptop belonging to Tsarnaev while Phillipos acted as a lookout. The backpack was discarded, but police recovered it and its contents in a nearby New Bedford landfill on April 26. During interviews, the men initially denied visiting the dorm room but later admitted their actions.[232][237]

Arrests and legal proceedings

[edit]Police arrested Kadyrbayev and Tazhayakov at the off-campus housing complex during the night of April 18–19. An unidentified girlfriend of one of the men was also arrested,[235][236] but all three were soon released.[232]

Kadyrbayev and Tazhayakov were re-arrested in New Bedford on April 20 and held on immigration-related violations. They appeared before a federal immigration judge on May 1 and were charged with overstaying their student visas.[238][239][240] That same day, they were charged criminally with:

willfully conspir(ing) with each other to commit an offense against the United States... by knowingly destroying, concealing, and covering up objects belonging to Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, namely, a backpack containing fireworks and a laptop computer, with the intent to impede, obstruct, and influence the criminal investigation of the Marathon bombing.[241][242]

Kadyrbayev and Tazhayakov were indicted by a federal grand jury on August 8, 2013, on charges of conspiracy to obstruct justice for helping Dzhokhar Tsarnaev dispose of a laptop computer, fireworks, and a backpack after the bombing. Each faced up to 25 years in prison and deportation if convicted.[243] Tazhayakov was convicted of obstruction of justice and conspiracy on July 21, 2014.[244]

Kadyrbayev pleaded guilty to obstruction charges on August 22, 2014,[245] but sentencing was delayed pending the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Yates v. United States.[246] Kadyrbayev was sentenced to six years in prison in June 2015.[247] He was deported to Kazakhstan in October 2018.[248]

Tazhayakov pleaded not guilty and went to trial, arguing that "Kadyrbayev was the mastermind behind destroying the evidence and that Tazhayakov only 'attempted obstruction'." Jurors returned a guilty verdict, however, and he was sentenced to 42 months (3+1⁄2 years) in prison in June 2015. U.S. District Judge Douglas Woodlock gave a lighter sentence to Tazhayakov than to Kadyrbayev, who was viewed as more culpable.[247] Tazhayakov was released in May 2016 and subsequently deported.[249]

Phillipos was arrested and faced charges of knowingly making false statements to police.[232][233] He was released on $100,000 bail ($130,800 in 2023 dollars) and placed under house confinement with an ankle monitor.[234] He was convicted on October 28, 2014, on two charges of lying about being in Tsarnaev's dorm room. He later acknowledged that he was in the room while two friends removed a backpack containing potential evidence relating to the bombing.[250]

Phillipos faced a maximum sentence of eight years' imprisonment on each count.[251] In June 2015, U.S. District Judge Douglas P. Woodlock sentenced him to three years in prison.[252] Phillipos filed an appeal, but his sentence was upheld in court on February 28, 2017.[253]

Phillipos was released from prison in Philadelphia on February 26, 2018, and began serving a three-year probationary period.[254]

Ibragim Todashev

[edit]On May 22, the FBI interrogated Ibragim Todashev in Orlando, Florida, who was a Chechen from Boston. The New York Times quoted an unnamed law enforcement official as saying that Todashev had confessed to a triple homicide, and had implicated Tsarnaev as well.[255] During the interrogation, he was shot and killed by an FBI agent who claimed that Todashev attacked him.[256] Todashev's father claimed his son was innocent and that federal investigators were biased against Chechens and made up their case against him.[257]

Khairullozhon Matanov

[edit]Matanov was originally from Kyrgyzstan. He came to the U.S. in 2010 on a student visa, and later claimed asylum. He attended Quincy College for two years before dropping out to become a taxicab driver. He was living in Quincy, Massachusetts, at the time of his arrest, and was a friend of Tamerlan Tsarnaev.[258]

A federal indictment was unsealed against Khairullozhon Matanov on May 30, 2014, charging him with "one count of destroying, altering, and falsifying records, documents, and tangible objects in a federal investigation, specifically information on his computer, and three counts of making materially false, fictitious, and fraudulent statements in a federal terrorism investigation". Matanov bought dinner for the two Tsarnaev brothers 40 minutes after the bombing. After the Tsarnaev brothers' photos were released to the public, Matanov viewed the photos on the CNN and FBI websites before attempting to reach Dzhokhar and then tried to give away his cell phone and delete hundreds of documents from his computer. Prosecutors said that Matanov attempted to mislead investigators about the nature of his relationship with the brothers and to conceal that he shared their philosophy of violence.[259][258]

In March 2015, Matanov pleaded guilty to all four counts.[258][260] In June 2015, he was sentenced to 30 months in prison.[258]

Victims

[edit]Deaths

[edit]Three people were killed as a direct result of the bombings. Krystle Marie Campbell, a 29-year-old restaurant manager from Medford, Massachusetts, was killed by the first bomb.[261][35] Lü Lingzi (Chinese: 吕令子),[262][263] a 23-year-old Chinese national and Boston University graduate student from Shenyang, Liaoning,[264][265][266][267][268] and 8-year-old Martin William Richard from the Dorchester neighborhood of Boston, were both killed by the second bomb.[269][270]

Sean Allen Collier, 27 years old, was shot and killed by the bombers as he sat in his patrol car on April 18, at about 10:25 p.m. He was an MIT police officer, and had been with the Somerville Auxiliary Police Department from 2006 to 2009.[271][272] He died from multiple gunshot wounds.[273]

Boston Police Department officer Dennis Simmonds died on April 10, 2014, from head injuries he received during the Watertown shootout a year before.[64]

Injuries

[edit]

About 281 civilians were treated at 27 local hospitals.[5][276] Eleven days later, 29 remained hospitalized, one in critical condition.[277] Many victims had lower leg injuries and shrapnel wounds,[278] which indicated that the devices were low to the ground.[279] At least 16 civilians lost limbs, at the scene or by surgical amputation, and three lost more than one limb.[280][281][282][283]

Doctors described removing "ball-bearing type" metallic beads a little larger than BBs and small carpenter-type nails about 0.5 to 1 inch (1 to 3 cm) long.[284] Similar objects were found at the scene.[51] The New York Times cited doctors as saying that the bombs mainly injured legs, ankles, and feet because they were low to the ground, instead of fatally injuring abdomens, chests, shoulders, and heads.[285] Some victims had perforated eardrums.[279]

MBTA police officer Richard H. Donohue Jr. (33) was critically wounded during a firefight with the bombers just after midnight on April 19.[96] He lost almost all of his blood, and his heart stopped for 45 minutes, during which time he was kept alive by cardiopulmonary resuscitation.[citation needed] The Boston Globe reported that Donohue may have been accidentally shot by a fellow officer.[97]

Marc Fucarile lost his right leg and received severe burns and shrapnel wounds. He was the last victim released from hospital care on July 24, 2013.[286]

Reactions

[edit]Law enforcement, local and national politicians, and various heads of state reacted quickly to the bombing, generally condemning the act and expressing sympathies for the victims.[52][287] Spontaneous, improvised temporary memorials appeared at the sites of the deaths in Boston and Cambridge. Over the next few years, permanent memorials were constructed and dedicated at these locations.

Aid to victims

[edit]The One Fund Boston was established by Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick and Boston mayor Thomas Menino to make monetary distributions to bombing victims.[288][289] The Boston Strong concert at the TD Garden in Boston on May 30, 2013, benefitted the One Fund, which ultimately received more than $69.8 million in donations.[290] A week after the bombing, crowdfunding websites[291] received more than 23,000 pledges promising more than $2 million for the victims, their families, and others affected by the bombing.[292] The Israel Trauma Coalition for Response and Preparedness sent six psychologists and specialists from Israel to help Boston emergency responders, government administrators, and community people develop post-terrorist attack recovery strategies.[293]

Local reactions

[edit]Numerous sporting events, concerts, and other public entertainment were postponed or canceled in the days following the bombing.[295][296][297][298] The MBTA public transit system was under heavy National Guard and police presence and it was shut down a second time April 19 during the manhunt.[74][116][299]

In the days after the bombing, makeshift memorials began to spring up along the cordoned-off area surrounding Boylston Street. The largest was located on Arlington Street, the easternmost edge of the barricades, starting with flowers, tokens, and T-shirts.[300][301][302][303][304] In June, the Makeshift Memorial located in Copley Square was taken down and the memorial objects located there were moved to the archives in West Roxbury for cleaning, fumigation, and archiving.[305]

Five years after the bombing, The Boston Globe reported all of the items from the memorials were being housed in a climate controlled environment, free of charge, by the storage company, Iron Mountain in Northborough, Massachusetts. Some of the items are also being stored in Boston's city archives in West Roxbury.[306]

Boston University established a scholarship in honor of Lü Lingzi, a student who died in the bombing.[307] University of Massachusetts Boston did the same in honor of alumna and bombing victim Krystle Campbell.[308]

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology established a scholarship, and erected a large abstract environmental sculpture outdoors called the Sean Collier Memorial, both in memory of slain MIT Police officer Sean Collier. The open-arched monolithic stone enclosure was proposed, designed, funded, fabricated, and installed on campus in less than two years after the bombing, and formally unveiled on April 29, 2015.[309][310]

One study conducted by the Institute for Public Service at Suffolk University in Boston, Massachusetts, recorded the mental health and emotional response of various survivors, for three years following the bombing. In doing so, it reviewed the kinds of aid that were available in local hospitals and offered advice on how a person or community may be healed.[311] This study also mentions that after recognizing the downgraded media coverage of people in the city being killed or injured on a daily basis, the city of Boston "applied for and received a grant from The Rockefeller Foundation to be part of their 100 resilient cities network and to develop a cross cutting resilience strategy".[312]

However, there was rising anti-Muslim sentiment online and locally in the weeks following the bombing, causing distress in the local Muslim community and making some afraid to leave their homes.[313]

Three stone pillars lit by abstract sculptural bronze lighting columns memorializing three victims were installed at the two separate bombing sites on August 19, 2019.[294] Two bronze sidewalk bricks were installed to memorialize police officers killed in the aftermath, and cherry trees were planted nearby to bloom each April.[294]

The Catholic bishops of Massachusetts opposed the death penalty for terrorist bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, citing the need to build a culture of life.[314]

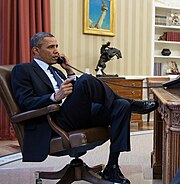

National reactions

[edit]President Barack Obama addressed the nation after the attack.[315] He said that the perpetrators were still unknown, but that the government would "get to the bottom of this" and that those responsible "will feel the full weight of justice".[316] He ordered flags to half-staff until April 20 on all federal buildings as "a mark of respect for the victims of the senseless acts of violence perpetrated on April 15, 2013 in Boston, Massachusetts".[317]

Moments of silence were held at various events across the country, including at the openings of the New York Stock Exchange, NASDAQ, and NYMEX on the day after the bombing.[318] Numerous special events were held, including marathons and other runs.[319][320][321][322] Islamic organizations in the United States condemned the attacks.[323]

International reactions

[edit]

The bombing was denounced and condolences were offered by many international leaders as well as leading figures from international sport. Security measures were increased worldwide in the wake of the attack.[324][325][326][327]

In China, users posted condolence messages on Weibo in response to the death of Lü Lingzi.[328][329] Chris Buckley of The New York Times said "Ms. Lu's death gave a melancholy face to the attraction that America and its colleges exert over many young Chinese."[265] Laurie Burkitt of The Wall Street Journal said "Ms. Lu's death resonates with many in China" due to the one-child policy.[330]

Organizers of the London Marathon, which was held six days after the Boston bombing, reviewed security arrangements for their event. Hundreds of extra police officers were drafted in to provide a greater presence on the streets, and a record 700,000 spectators lined the streets. Runners in London observed a 30-second silence in respect for the victims of Boston shortly before the race began, and many runners wore black ribbons on their vests. Organizers also pledged to donate US$3 to a fund for Boston Marathon victims for every person who finished the race.[331][332][333]

Organizers of the 2013 Vancouver Sun Run, which was held on April 21, 2013, donated $10 from every late entry for the race to help victims of the bombing at the Boston Marathon. Jamie Pitblado, vice-president of promotions for The Vancouver Sun and The Province, said the money would go to One Fund Boston, an official charity that collected donations for the victims and their families. Sun Run organizers raised anywhere from $25,000 to $40,000. There were over 48,000 participants, many dressed in blue and yellow (Boston colors) with others wearing Boston Red Sox caps.[334]

Petr Gandalovic, ambassador of the Czech Republic, released a statement after noticing much confusion on Facebook and Twitter between his nation and the Chechen Republic. "The Czech Republic and Chechnya are two very different entities – the Czech Republic is a Central European country; Chechnya is a part of the Russian Federation."[335]

Security was also stepped up in Singapore in response to online threats made on attacking several locations in the city-state and the Singapore Marathon in December. Two suspects were investigated and one was eventually arrested for making false bomb threats.[336]

David Cameron (prime minister of the United Kingdom) posted on Twitter, "The scenes from Boston are shocking and horrific - my thoughts are with all those who have been affected."[337] On May 14, he visited Boston as part of a three-day visit to the United States. In Boston, he met with Governor Patrick at the Massachusetts State House, offering condolences and holding a discussion with Patrick about what lessons governments could learn from the bombings. Afterwards, he and Patrick visited the temporary memorials at Copley Square, where Cameron remarked to reporters, "Everyone in the UK stands with [Boston] and [its] great people."[338][339]

Russian reaction

[edit]The Russian government said that special attention would be paid to security at upcoming international sports events in Russia, including the 2014 Winter Olympics.[340] According to the Russian embassy in the U.S., President Vladimir Putin condemned the bombing as a "barbaric crime" and "stressed that the Russian Federation will be ready, if necessary, to assist in the U.S. authorities' investigation".[341] He urged closer cooperation of security services with Western partners[342] but other Russian authorities and mass media blamed the U.S. authorities for negligence as they warned the U.S. of the Tsarnaevs.[343] Moreover Russian authorities and mass media since the spring of 2014 blame the United States for politically motivated false information about the lack of response from Russian authorities after subsequent U.S. requests.[citation needed] As proof a letter from the Russian FSB was shown to the members of an official U.S. Congressional delegation to Moscow during their visit. This letter with information about Tsarnaev (including his biography details, connections and phone number) had been sent from the FSB to the FBI and CIA during March 2011.[344]

Republican U.S. Senators Saxby Chambliss and Richard Burr reported that Russian authorities had separately asked both the FBI (at least twice: during March and November 2011) and the CIA (September 2011) to look carefully into Tamerlan Tsarnaev and provide more information about him back to Russia.[345] FSB secretly recorded phone conversations between Tamerlan Tsarnaev and his mother (they vaguely and indirectly discussed jihad) and sent these to the FBI as evidence of possible extremist links within the family.[citation needed] However, while Russia offered US intelligence services warnings that Tsarnaev planned to link up with extremist groups abroad, an FBI investigation yielded no evidence to support those claims at the time. In addition, subsequent U.S. requests for additional information about Tsarnaev went unanswered by the Russians.[346][failed verification]

Chechen reactions

[edit]On April 19, 2013, the press secretary of the head of the Chechen Republic, Ramzan Kadyrov, issued a statement that, inter alia, read: "The Boston bombing suspects have nothing to do with Chechnya".[347][348] On the same day, Kadyrov was reported by The Guardian to have written on Instagram:[349]

Any attempt to make a link between Chechnya and the Tsarnaevs, if they are guilty, is in vain. They grew up in the U.S., their views and beliefs were formed there. The roots of evil must be searched for in America. The whole world must battle with terrorism. We know this better than anyone. We wish recover [sic] to all the victims and share Americans' feeling of sorrow.

Akhmed Zakayev, head of the secular wing of the Chechen separatist movement, now in exile in London, condemned the bombing as "terrorist" and expressed condolences to the families of the victims. Zakayev denied that the bombers were in any way representative of the Chechen people, saying that "the Chechen people never had and can not have any hostile feelings toward the United States and its citizens".[350]

The Mujahideen of the Caucasus Emirate Province of Dagestan, the Caucasian Islamist organization in both Chechnya and Dagestan, denied any link to the bombing or the Tsarnaev brothers and stated that it was at war with Russia, not the United States. It also said that it had sworn off violence against civilians since 2012.[351][352][353]

Criticism of the "shelter-in-place" directive and house-to-house searches

[edit]During the manhunt for the perpetrators of the bombing, Governor Deval Patrick said "we are asking people to shelter in place". The request was highly effective; most people stayed home, causing Boston, Watertown, and Cambridge to come to a virtual standstill. According to Time magazine, "media described residents complying with a 'lockdown order,' but in reality the governor's security measure was a request". Scott Silliman, emeritus director of the Center on Law, Ethics and National Security at Duke Law School, said that the shelter-in-place request was voluntary.[354]

The National Lawyers Guild and some news outlets questioned the constitutionality of the door-to-door searches conducted by law enforcement officers looking for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.[355][356][357]

One Boston Day

[edit]On the second anniversary of the Boston Marathon Bombings, Mayor Marty Walsh established April 15, the day of the bombings, as an official and permanent holiday called "One Boston Day", dedicated to conducting random acts of kindness and helping others out.[358] Over the past eight years, some examples of acts of kindness being done have been donating blood to the American Red Cross, donating food to the Greater Boston Food Bank, opening free admission in places like the Museum of Science and Museum of Fine Arts, donating shoes to homeless shelters, and donating to military and veteran charities.[359][360]

Conspiracy theories

[edit]A number of conspiracy theories arose in the immediate wake of the attacks and after more information about the Tsarnaev brothers came to light.[361] This can be common in the aftermath of acts of domestic terrorism, especially the September 11 attacks.[362]

Stella Tremblay, then a member of the New Hampshire House of Representatives from Auburn, New Hampshire, claimed the Boston Marathon bombing was a government conspiracy and that victims who lost their legs were faking their injuries because they were not "screaming in agony." Under pressure afterwards she resigned. The New Hampshire House then unanimously passed a resolution to show support for the victims and to disavow unfounded speculation or accusations.[363][364]

In the days following the attacks, some conspiracy theories arose on the internet claiming they were false flag attacks committed by the United States government.[365] As more information about the backgrounds of the Tsarnaev Brothers came to light, further conspiracy theories were disseminated. One claim, made by Dzhokhar Tsarnaev's defense attorney as well as some journalists, was that the FBI had tried to recruit Tamerlan Tsarnaev as an FBI informant in 2011.[182][183][184][185] The FBI denied this claim in a press release, stating that "the Tsarnaev brothers were never sources for the FBI nor did the FBI attempt to recruit them as sources".[366] The FBI is not required to release information on informants, and classified information on sources of intelligence constitutes an exception to the 25-year declassification window established by Executive Order 13526.[367]

In 2011, a triple murder took place in Waltham, Massachusetts, in which a friend of Tamerlan Tsarnaev was one of the victims.[368][369][370] After the 2013 attacks, the investigation was reopened with Tamerlan Tsarnaev as a new suspect.[371] The failure of the 2011 investigation to identify Tamerlan Tsarnaev as a major suspect led to claims among conspiracy theorists that the investigation of the 2011 triple murder had been suppressed by the FBI in order to maintain Tsarnaev's informant status. Theorists also cite the fact that the FBI has been criticized for an alleged practice under former director James Comey of encouraging confidential informants to attempt terrorist attacks.[372][373] This alleged practice, combined with disputed claims of connections between the Tsarnaev brothers and intelligence services,[182][374] have given rise to a conspiracy theory that the United States government had foreknowledge of the Tsarnaev brothers' plans to commit a terrorist attack, or that the attack was made at the direction of intelligence services.[361] The Tsarnaev brother's uncle, Said-Hussein Tsarnaev, and other members of the Tsarnaev family have repeated this theory, as well as claiming neither brother actually committed the attacks.[375] This claim also formed an element of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev's legal defense.[376] No evidence or further claims supporting this theory have been confirmed by any US government agencies.[361]

Conflicting reports

[edit]On the afternoon of the bombing, the New York Post reported that a suspect, a Saudi Arabian male, was under guard and being questioned at a Boston hospital.[377] That evening, Boston Police Commissioner Ed Davis said that there had not been an arrest.[378] The Post did not retract its story about the suspect, leading to widespread reports by CBS News, CNN, and other media that a Middle Eastern suspect was in custody.[379] The day after the bombing, a majority of outlets were reporting that the Saudi was a witness, not a suspect.[380]

The New York Post on its April 18 front page showed two men, and said they were being sought by the authorities. The two men in question, a 17-year-old boy and his track coach, were not the ones being sought as suspects. The boy, from Revere, Massachusetts, turned himself over to the police immediately and was cleared after a 20-minute interview in which they advised him to deactivate his Facebook account.[381][382] New York Post editor Col Allan stated, "We stand by our story. The image was emailed to law enforcement agencies yesterday afternoon seeking information about these men, as our story reported. We did not identify them as suspects." The two were implied to be possible suspects via crowdsourcing on the websites Reddit[382] and 4chan.[383]

Several other people were mistakenly identified as suspects.[384] Two of those wrongly identified as suspects on Reddit were the 17-year-old track star noted above and Sunil Tripathi, a Brown University student missing since March.[385][386] Tripathi was found dead on April 23 in the Providence River.[387]

On April 17, the FBI released the following statement:

Contrary to widespread reporting, no arrest has been made in connection with the Boston Marathon attack. Over the past day and a half, there have been a number of press reports based on information from unofficial sources that has been inaccurate. Since these stories often have unintended consequences, we ask the media, particularly at this early stage of the investigation, to exercise caution and attempt to verify information through appropriate official channels before reporting.[388][389]

The decision to release the photos of the Tsarnaev brothers was made in part to limit damage done to those misidentified on the Internet and by the media, and to address concerns over maintaining control of the manhunt.[70]

See also

[edit]- 2011 Waltham triple murder, a triple homicide to which Tamerlan Tsarnaev has been connected

- Centennial Olympic Park bombing, a 1996 terrorist attack which also targeted a public event

- List of Islamist terrorist attacks

Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Straw, Joseph; Ford, Bev; McShane, Lawrence (April 17, 2013). "Police narrow in on two suspects in Boston Marathon bombings". The Daily News. New York. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ Cooper, Michael; Schmidt, Michael S.; Schmitt, Eric (April 23, 2013). "Boston Suspects Are Seen as Self-Taught and Fueled by Web". The New York Times. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ a b "Boston bombings suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev left note in boat he hid in, sources say". CBS. May 16, 2013. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ "Boston bombing: Tsarnaev's death sentence could be reinstated". March 22, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ a b c Kotz, Deborah (April 24, 2013). "Injury toll from Marathon bombs reduced to 264". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

Boston public health officials said Tuesday that they have revised downward their estimate of the number of people injured in the Marathon attacks, to 264.

- ^ a b "What we know about the Boston bombing and its aftermath". CNN. April 19, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ a b Estes, Adam Clark; Abad-Santos, Alexander; Sullivan, Matt (April 15, 2013). "Explosions at Boston Marathon Kill 3 — Now, a 'Potential Terrorist Investigation'". The Atlantic Wire. Archived from the original on November 16, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ Fromer, Frederic J. (April 15, 2013). "Justice Department Directing Full Resources To Investigate Boston Marathon Bombings". Huffington Post. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^ des Lauriers, Richard (April 18, 2013). "Remarks of Special Agent in Charge at Press Conference on Bombing Investigation". FBI. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ^ Tanfani, Joseph; Kelly, Devin; Muskal, Michael (April 19, 2013). "Boston bombing [Update]: Door-to-door manhunt locks down city". Los Angeles Times. Boston. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

As family members called on him to surrender, a 19-year-old college student remained on the run Friday as thousands of police armed with rifles and driving armored vehicles combed the nearly deserted streets of a region on virtual lockdown

- ^ "Boston Lockdown 'Extraordinary' But Prudent, Experts Say". NPR. April 22, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ "An empty metropolis: Bostonians share photos of deserted streets". April 19, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ "Two unnamed officials say Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, 19, did not have a gun when he was captured Friday in a Watertown, Mass. backyard. Boston Police Commissioner Ed Davis said earlier that shots were fired from inside the boat." The Associated Press Wednesday, April 24, 2013, 8:42 PM.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Seelye, Katharine Q.; Cooper, Michael; Rashbaum, William K. (April 19, 2013). "Boston bomb suspect is captured after standoff". The New York Times. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c d O'Neill, Ann (March 4, 2015). "Tsarnaev trial: Timeline of the bombings, manhunt and aftermath". CNN.

- ^ a b Seelye, Katherine Q. (April 23, 2013). "Bombing Suspect Cites Islamic Extremist Beliefs as Motive". The New York Times. et al. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ a b "United States vs. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, Case 1:13-mj-02106-MBB" (PDF). United States Department of Justice. April 21, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 23, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^ Markon, Jerry; Horwitz, Sari; Johnson, Jenna (April 22, 2013). "Dzhokhar Tsarnaev charged with using 'weapon of mass destruction'". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ "Dzhokhar Tsarnaev: Boston Marathon bomber found guilty". BBC News. April 8, 2015. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ "What Happened To Dzhokhar Tsarnaev? Update On Boston Marathon Bomber Sentenced To Death". International Business Times. April 16, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ a b Monge, Sonia (July 31, 2020). "Appeals court vacates Boston Marathon bomber's death sentence, orders new penalty trial". CNN. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ "United States v. Tsarnaev". Oyez. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ a b de Vogue, Arinna (March 22, 2021). "Supreme Court agrees to review Boston Marathon bomber's death penalty case". CNN. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c Abel, David; Silva, Steve; Finucane, Martin (April 15, 2013). "Explosions rock Boston Marathon finish line; dozens injured". The Boston Globe (online ed.). Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ a b "Source: Investigators recover circuit board believed used to detonate Boston Marathon blasts". The Boston Globe (online ed.). April 16, 2013. Archived from the original on April 18, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ Winter, Michael (April 16, 2013). "At least 3 dead, 141 injured in Boston Marathon blasts". USA Today. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Levs, Joshua; Plott, Monte (April 16, 2013). "Terrorism strikes Boston Marathon as bombs kill 3, wound scores". CNN. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Preston, Jennifer; Stack, Liam (April 22, 2013). "Updates in the Aftermath of the Boston Marathon Bombing: Their Stories: The People at the Finish Line". The New York Times. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e McClam, Erin (April 15, 2013). "Explosions rock finish of Boston Marathon; 2 killed and at least 23 hurt, police say". NBC News. Archived from the original on April 27, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ Malone, Scott; Pressman, Aaron (April 21, 2008). "Triumph turns to terror as blasts hit Boston Marathon". The Guardian. London. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ a b c Eligon, John; Cooper, Michael (April 15, 2013). "Boston Marathon Blasts Kill 3 and Maim Dozens". The New York Times. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ Benjamin, Amalie (April 15, 2013). "Events force BAA to alter course at Marathon". The Boston Globe. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ Florio, Michael (April 15, 2013). "Joe Andruzzi handles Boston Marathon attack the way Joe Andruzzi would". Sports. NBC. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ Greene, William (April 16, 2013). "Former Patriots offensive lineman Joe Andruzzi carried an injured woman away from the scene". The Boston Globe. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c Liptak, Adam (March 4, 2022). "Supreme Court Restores Death Sentence for Boston Marathon Bomber". The New York Times.

- ^ McLaughlin, Tim (April 16, 2013). "A shaken Boston mostly gets back to work; 12-block crime scene". Reuters. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ "Police will have controlled explosion on 600 block on Boylston Street, a block beyond the finish line". Boston. Twitter. April 15, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ "Mass. gov: No unexploded bombs at Boston Marathon". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 18, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Trotter, J. K. (April 16, 2013). "What Happened at Boston's JFK Library?". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 10, 2024.

- ^ "3/2050 NOTAM Details". Federal Aviation Administration. April 15, 2013. Archived from the original on April 18, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ Sullivan, Eileen (April 15, 2013). "Cellphone use heavy, but still operating in Boston". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 30, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ "Live Updates: Explosions at Boston Marathon". The Washington Times (live stream from scene). April 15, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ "American Red Cross Statement on Boston Marathon Explosions". American Red Cross. April 15, 2013. Archived from the original on April 18, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Boston Marathon Explosions: Third Blast". Sky News. April 15, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ "Boston Marathon Explosions". Person Finder. April 15, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ "3 killed, more than 140 hurt in Boston Marathon bombing". CNN. April 16, 2013. Archived from the original on April 19, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Hosenball, Mark; Herbst-Bayliss, Svea (April 16, 2013). "Investigators scour video, photos for Boston Marathon bomb clues". GlobalPost. Thomson Reuters. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "North Korea Adamantly Denies Conspiracy Theory Linking It to Boston Bombing". Business Insider.

- ^ "North Korea Denies Any Link to Boston Marathon Bombs, but Says It Still May Strike US". International Business Times. April 24, 2013.

- ^ Bengali, Shashank; Muskal, Michael (April 16, 2013). "Live updates: Obama calls Boston bombings a 'heinous, cowardly' act of terror". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c McLaughlin, Tim; Herbst-Bayliss, Svea (April 17, 2013). "Boston bomb suspect spotted on video, no arrest made". Reuters. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ a b "FBI seeks images in Boston Marathon bomb probe; new details emerge on explosives". News. CBS. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ Lister, Tim; Cruickshank, Paul (April 17, 2013). "Boston Marathon bombs similar to 'lone wolf' devices, experts say". CNN. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ Ellement, John; Ballou, Brian (April 17, 2013). "Boston Medical Center reports five-year-old boy in critical condition, 23 victims treated from Boston Marathon bombings". The Boston Globe. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- ^ "Feds Race to Trace Boston Marathon Pressure Cooker Bomb". ABC. April 17, 2013. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ Isikoff, Michael (April 23, 2013). "Search of Tsarnaevs' phones, computers finds no indication of accomplice, source says". NBC News. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ Vinograd, Cassandra; Dodds, Paisley (April 16, 2013). "AP Glance: Pressure Cooker Bombs". Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 13, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Inspire Magazine: A Staple Of Domestic Terror". Anti-Defamation League. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ a b Serrano, Richard A.; Mason, Melanie; Dilanian, Ken (April 23, 2013). "Boston bombing suspect describes plot". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 25, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ Dezenski, Lauren (April 23, 2013). "Older Marathon bombing suspect purchased fireworks at N.H. store, official says". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Valencia, Milton J. (April 21, 2013). "Boston Police Commissioner Edward Davis says releasing photos was 'turning point' in Boston Marathon bomb probe". The Boston Globe. Boston. Retrieved April 10, 2015.

- ^ "He loved us, and we loved him". MIT. April 19, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ Sherman, Pat (April 21, 2013). "UCSD professor says Boston Marathon was 'lone wolf' terrorism". La Jolla Light. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ^ a b c Ransom, Jan (May 28, 2015). "Death benefit given to family of officer wounded in Tsarnaev shootout". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ a b Loder, Asjylyn; Deprez, Esmé E. (April 19, 2013). "Boston Bomb Victim in Photo Helped Identify Suspects". Bloomberg. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ^ "Bomb victim whose legs were blown off reportedly helped FBI id suspect". Fox. April 19, 2013. Archived from the original on April 19, 2013.

- ^ Seelye, Katharine Q.; Cooper, Michael; Schmidt, Michael S. (April 18, 2013). "FBI Releases Images of Two Suspects in Boston Attack". The New York Times. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ "Updates on Investigation Into Multiple Explosions in Boston". The FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation. Department of Justice. April 18, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ a b Smith, Matthew; Patterson, Thomas (April 19, 2013). "FBI: Help us ID Boston bomb suspects". CNN. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ a b Montgomery, David; Horwitz, Sari; Fisher, Marc (April 20, 2013). "Police, citizens and technology factor into Boston bombing probe". The Washington Post.

- ^ Yashwant Raj, "Boston Bomber Partied with Friends after Attack" Archived June 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Hindustan Times, April 22, 2013.

- ^ Valencia, Milton J.; Wen, Patricia; Cullen, Kevin; Ellement, John R.; Finucane, Martin (March 4, 2015). "Defense admits Tsarnaev took part in Marathon bombings". The Boston Globe. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ "Police believe Tsarnaev brothers killed officer for his gun". CBS News. April 23, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c Murphy, Shelley; Valencia, Milton J.; Lowery, Wesley; Johnson, Akilah; Moskowitz, Eric; Wangsness, Lisa; Ellement, John R. (April 19, 2013). "Search for marathon bombing suspect locks down Watertown, surrounding communities". The Boston Globe. Retrieved April 19, 2013. Originally titled "Chaos in Cambridge, Watertown after fatal shooting".

- ^ "Police: MIT police officer fatally shot, gunman sought". WHDH.com. Sunbeam Television. April 19, 2013. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ "Boston bombing jurors see dramatic video of carjack victim's escape". CBS News. CBS/AP. March 12, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- ^ Chinese name from: "《爱国者日》上映 再现波马爆炸案 留学生孟盾事迹搬..." The China Press. January 13, 2017. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ a b Gorman, Siobhan; Barrett, Devlin (April 25, 2013). "Judge Made Miranda-Rights Call in Boston Bombing Case". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "Suburb becomes war zone in days after bombings". Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^ a b Finn, Peter; Leonnig, Carol D.; Englund, Will (April 19, 2013). "Tamerlan Tsarnaev and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev were refugees from brutal Chechen conflict". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ "Details Emerge of Alleged Carjacking by Bomber Suspects". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^ Harris, Dan (April 23, 2013). "Alleged Bombers' Carjack Victim Barely Escaped Grab as He Bolted". ABC News. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "From fear to cheers: The final hours that paralyzed Boston". CNN. April 28, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ a b "Police chief: Boston manhunt began with intense firefight in dark street". CNN. April 20, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c Carter, Chelsea J.; Botelho, Gregory (April 20, 2013). "'Captured!!!' Boston police announce Marathon bombing suspect in custody". CNN.

• a:"Richard H. Donohue Jr., 33,... was shot and wounded in the incident... Another 15 police officers were treated for minor injuries sustained during the explosions and shootout". - ^ a b Arsenault, Mark; Murphy, Sean P (April 21, 2013). "Marathon bombing suspects threw 'crude grenades' at officers". The Boston Globe Metro. Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^ Estes, Adam Clark (April 2013). "An Officer's Been Killed and There's a Shooter on the Loose in Boston". The Atlantic Wire. Archived from the original on April 19, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ Leger, Donna (April 22, 2013). "Police chief details chase, capture of bombing suspects". USA Today. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^ a b c DeWitt, Vincent (July 8, 2013). "Watertown Mass. Police describe takedown of Boston Marathon bombers". New York Post. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ a b Smith, Tovia (March 25, 2016). "Filming For Marathon Bombing Movie Stirs Emotions In Boston". NPR. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ "The First Photos of The Boston Bombing Suspects' Shootout With Police". Dead spin. Archived from the original on May 3, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ "Boston Bombing Suspect Shootout Pictures". Get on hand. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ "102 hours in pursuit of Marathon suspects". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 21, 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ^ "Boston Marathon bomb suspect still at large". BBC News. April 20, 2013. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ^ Bidgood, Jess (May 4, 2013). "Autopsy Says Boston Bombing Suspect Died of Gunshot Wounds and Blunt Trauma". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "MBTA Police Officer Shot While Chasing Bombing Suspects". WBZ. CBS Radio. April 19, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ a b "Bullet that nearly killed MBTA police officer in Watertown gunfight appears to have been friendly fire". Boston. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ^ "Donohue Talks Miracle Survival On Toucher & Rich: 'I Don't Have An Explanation For It'". CBS Boston. April 15, 2014.

- ^ Schworm, Peter; Cramer, Maria (April 30, 2013). "Harvard report praises response to Marathon bombings". The Boston Globe.

- ^ "Boston Bombing Suspects, Tzarnaev Brothers, Had One Gun During Shootout With Police: Officials". Huffington Post. April 24, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ Date, Jack; Mosk, Matthew (April 24, 2013). "Single Gun Recovered From Accused Bombers". ABC The Blotter. ABC News. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ^ "Green Honda could prove crucial if Tsarnaev charged in MIT officer's killing – Investigations". Investigations.nbcnews.com. August 29, 2010. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- ^ Helmuth, Laura (April 19, 2013). "Pronounce Boston bomb names: Listen to recording of names of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, Tamerlan Tsarnaev". Slate. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Abad-Santos, Alexander (April 19, 2013). "Who Is Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the Man at the Center of the Boston Manhunt?". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 19, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ Naughton, Philippe (April 19, 2013). "Live: Boston bomb suspect killed by police, one hunted". The Times. UK. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ "Officials in Watertown field calls from worried residents – Watertown – Your Town". The Boston Globe. April 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ Boston, Belmont, Brookline, Cambridge, Newton, and Waltham

- ^ "Suburban police played a key role in bombing investigation". The Boston Globe. April 25, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

By 6 p.m. Friday, Governor Deval Patrick suspended the "shelter-in-place" order for Watertown, Belmont, Boston, Brookline, Cambridge, Newton, and Waltham after the manhunt came up empty.

- ^ "Important Public Safety Alert 4/19/13". Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Rawlings, Nate (April 19, 2013). "Was Boston Actually on Lockdown?". Time. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ "City of Somerville Safety Advisory". Somerville News. April 19, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2015.