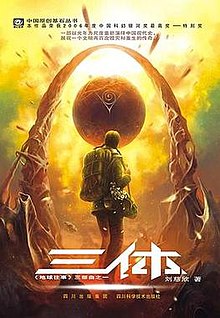

The Three-Body Problem (novel)

| |

| Author | Liu Cixin |

|---|---|

| Original title | 三体 |

| Translator | Ken Liu |

| Language | Chinese |

| Series | Remembrance of Earth's Past |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Chongqing Press |

Publication date | 2008 |

| Publication place | China |

Published in English | 2014 by |

| Pages | 390 |

| Awards |

|

| ISBN | 978-7-536-69293-0 |

| Followed by | The Dark Forest |

| The Three-Body Problem | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 三体 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 三體 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Three Body" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Three-Body Problem (Chinese: 三体; lit. 'three body') is a 2008 novel by the Chinese science fiction author Liu Cixin. It is the first novel in the Remembrance of Earth's Past trilogy.[1] The series portrays a fictional past, present, and future wherein Earth encounters an alien civilization from a nearby system of three Sun-like stars orbiting one another, a representative example of the three-body problem in orbital mechanics.

The story was originally serialized in Science Fiction World in 2006 before it was published as a standalone book in 2008.[2] In 2006, it received the Galaxy Award for Chinese science fiction.[3] In 2012, it was described as one of China's most successful full-length novels of the past two decades.[4] The English translation by Ken Liu was published by Tor Books in 2014.[5] That translation was the first novel by an Asian writer to win a Hugo Award for Best Novel;[6][7] it was also nominated for the Nebula Award for Best Novel.[8]

The book has been adapted into other media. In 2015, a Chinese film adaptation of the same name was in production, but it was never released. A Chinese TV series, Three-Body, released in early 2023 to critical success locally. An English-language Netflix series adaptation, 3 Body Problem, was released in March 2024.

Background

[edit]Liu Cixin was born in Beijing in June 1963. Before beginning his career as an author, he was a senior engineer working at a power plant in Shanxi province.[9][10] In 1989, he wrote Supernova Era and China 2185, but neither book was published at that time. His first published short story, Whalesong, was published in Science Fiction World in June 1999. The same year, his novel With Her Eyes won the Galaxy Award.[11][12] In 2000, he wrote The Wandering Earth, which also received the Galaxy Award[12] and was adapted into a film in 2019.[13] When the short story Mountain appeared in January 2006, many readers wrote that they hoped Liu would write a novel. He decided to concentrate on novel-length texts rather than short stories.[citation needed] Outside of Remembrance of Earth's Past, Liu's novels include Supernova Era and Ball Lightning. When not otherwise busy, Liu wrote 3,000–5,000 words a day; each of his books reportedly took about one year to complete.[14]

Plot

[edit]During China's Cultural Revolution, astrophysicist Ye Wenjie witnesses her father be beaten to death during a struggle session for teaching quantum physics. Ye is deported to a labor brigade in the Greater Khingan Mountains. She bonds with ecologist Bai Mulin, helping him write a petition to the government against the deforestation. Ye is framed by Bai for writing the letter, and is arrested. However, her academic background results in her recruitment by "Red Coast", a secret military initiative attempting to search for and communicate with extraterrestrial life.

Ye discovers a method to greatly amplify radio frequency transmissions using the Sun, and she secretly broadcasts a message. Eight years later, she receives a reply from the alien planet Trisolaris. Disillusioned by humanity's inability to live harmoniously with itself and nature, Ye invites the Trisolarans to Earth to help settle its problems.

After China's reforms, Ye encounters Mike Evans, heir to the world's largest oil company. Evans is a radical environmentalist who shares Ye's hatred of humanity. Ye confides in him her communications with Trisolaris. Evans uses his inherited financial power to create the militant and semi-secret Earth-Trisolaris Organization (ETO) as a fifth column for Trisolaris and appoints Ye its leader.

Through Trisolaris-ETO communications, Trisolaris is revealed to be a planet orbiting the ternary star system of Alpha Centauri.[a] Because of the three-body problem, the three stars' movements (and Trisolaris' position relative to them) are chaotic and unpredictable. As a result, Trisolaris experiences great climate extremes, alternating between temperate "Stable Eras" during which civilization thrives, and "Chaotic Eras" of climate catastrophes. The worst such catastrophes are civilization-ending. Hundreds of Trisolaran civilizations have risen and fallen, each attempting but failing to develop an accurate calendar that can predict and help prepare for Chaotic Eras. Moreover, the chaotic orbits threaten to eventually destroy Trisolaris by tidal forces or by direct collision with a star.

Upon reception of Ye's broadcasts, the current and technologically advanced Trisolaran civilization identifies Earth as a colonization target, which will permit the Trisolaran civilization to escape their inhospitable and ultimately-doomed home planet. It dispatches an invasion force on a 450-year journey to Earth.

However, the Trisolaran leadership is concerned that Earth's accelerating technological developments will outmatch the invasion force by the time of its arrival. Therefore, Trisolaris develops "sophons" (tiny supercomputers embedded in single protons by expanding their dimensions) in order to arrest Earth's technological development by interfering with its scientific experiments.

By the late-2000s/early-2010s, the sophon-induced apparent breakdown of science on Earth has prompted the suicides of several prominent scientists. These are noticed by Earth's governments, who form a task force to investigate. Beijing nanotechnologist Wang Miao and police detective Shi Qiang are recruited. Wang experiences paranormal phenomena, such as visions of a countdown to zero that stops when he ceases his research. As part of his investigations, Wang plays the sophisticated virtual reality video game Three Body. The game, which simulates Trisolaris, is created by the ETO with the purpose of identifying potential recruits and garnering sympathy for the Trisolaran plight.

Wang's successes in Three Body result in his induction into the ETO. He is invited to an ETO meeting, where Ye reveals to Wang the full extent of the conspiracy. Wang also witnesses the schism between the "Adventist" faction of the ETO, which views humanity as irredeemable and promotes its complete destruction by Trisolaris, and the "Redemptionist" faction, which aims to save the Trisolaran civilization by developing a solution to the three-body problem and producing an accurate calendar.

Tipped-off by Wang, Shi and the People's Liberation Army raid the meeting, arresting Ye and killing several ETO soldiers. An international military force then seizes the converted oil tanker housing ETO's communications with Trisolaris as it transits the Panama Canal. From these, Earth's governments learn of Trisolaris' existence and the approaching invasion force. Wang and his colleagues resolve to fight in Humanity's defence.

English translation

[edit]In 2012, Chinese-American science-fiction author Ken Liu and translator Joel Martinsen were commissioned by the China Educational Publications Import and Export Corporation (CEPIEC) to produce an English translation of The Three-Body Problem, with Liu translating the first and last volumes, and Martinsen translating the second.[15] In 2013, it was announced that the series would be published by Tor in the United States[16] and by Head of Zeus in the United Kingdom.[17]

Liu and Martinsen's translations contain footnotes explaining references to Chinese history that may be unfamiliar to international audiences. There are also some changes in the order of the chapters for the first volume. In the translated version, chapters which take place during the Cultural Revolution appear at the beginning of the novel rather than in the middle, as they were serialized in 2006 and appeared in the 2008 novel. According to the author, these chapters were originally intended as the opening, but were moved by his publishers to avoid attracting the attention of government censors.[15]

Characters

[edit]Ye family

[edit]- Ye Zhetai (叶哲泰)

- Physicist and professor at Tsinghua University. He is killed at a struggle session during the Cultural Revolution.

- Shao Lin (绍琳)

- Physicist and wife of Ye Zhetai. She denounces her husband in an act of self-preservation.

- Ye Wenjie (叶文洁)

- Astrophysicist and daughter of Ye Zhetai and Shao Lin. She is the first person to establish contact with Trisolaris while working at Red Coast. She marries Yang Weining with whom she has a daughter, Yang Dong. She later becomes the spiritual leader of the Earth-Trisolaris Organization (ETO).

- Ye Wenxue (叶文雪)

- Ye Wenjie's younger sister, a Tsinghua High School student and a zealous Red Guard. She is killed during factional violence at some point after the collapse of their family.

Red Coast Base

[edit]- Lei Zhicheng (雷志成)

- Political commissar at Red Coast Base. He recruits Ye Wenjie and oversees her work. He is murdered by Ye Wenjie after he discovers her secret communications with Trisolaris.

- Yang Weining (杨卫宁)

- Chief engineer at Red Coast Base, once a student of Ye Zhetai, later Ye Wenjie's husband and murdered by her alongside Lei Zhicheng.

Present-day

[edit]- Wang Miao (汪淼)

- Nanomaterials researcher and academician from the Chinese Academy of Sciences. He is tasked with investigating the ETO as well as the recent spate of suicides among well-known scientists. Wang Miao becomes immersed in the virtual reality game Three Body, through which he learns about Trisolaris.

- Yang Dong (杨冬)

- String theorist and daughter of Ye Wenjie and Yang Weining. She commits suicide shortly before the present day events.

- Ding Yi (丁仪)

- Theoretical physicist and Yang Dong's partner. He provides key insights to Wang Miao during his investigations. He was previously featured in Ball Lightning, another of Liu's works.

- Shi Qiang (史强)

- Police detective and counter-terrorism specialist, nicknamed "Da Shi" (大史; "Big Shi"). He has a crude demeanor but is highly dependable and often demonstrates keen insight. He assists Wang Miao in exposing the ETO.

- Chang Weisi (常伟思)

- Major-general of the People's Liberation Army who leads China's response to the ETO.

- Shen Yufei (申玉菲)

- Chinese-Japanese physicist. A leader of the "Redemptionist" faction of the ETO, she aims to develop a solution to the three-body problem that will save the Trisolaran civilization. She is murdered by her factional rival Pan Han.

- Wei Cheng (魏成)

- Math prodigy, recluse, and Shen Yufei's husband. With Shen's support, he develops a possible solution to the three-body problem.

- Pan Han (潘寒)

- Biologist, acquaintance of Shen Yufei and Wei Cheng. A leader of the "Adventist" faction of the ETO, he murders Shen Yufei to prevent the solving of the three-body problem, which will remove Trisolaris' incentive to invade Earth.

- Sha Ruishan (沙瑞山)

- Astronomer, one of Ye Wenjie's students.

- Mike Evans (麦克·伊文斯)

- Radical environmentalist who supports "pan-species communism", also son of an oil magnate. After meeting Ye Wenjie, he founds the ETO and provides its main source of funding. He leads the "Adventist" faction of the ETO, which views humanity as irredeemable and promotes its complete destruction by Trisolaris.

- Colonel Stanton (斯坦顿)

- Officer of the U.S. Marine Corps and commander of Operation Guzheng, which captures the ETO's communications with Trisolaris.

Inspiration

[edit]In Liu's early childhood, when he was three years old his family moved from the Beijing Coal Design Institute to Yangquan in Shanxi, due to his father changing jobs. He also spent a part of his childhood in the countryside around ancestral hometown of Luoshan, Henan. On 25 April 1970, Dong Fang Hong 1—China's first satellite—was launched. Liu remembered the launch as a pivotal event in his life, recalling a deep sense of longing on witnessing it.[18]

Several years later, Liu found a box of books under his bed in Yangquan, which included an anthology of Tolstoy, Moby-Dick, Journey to the Center of the Earth, and Silent Spring. Upon beginning to read Journey to the Center of the Earth, his father told him: "It's called science fiction, it's a creative writing based on science". This was his first encounter with the genre, and he later remarked: "My persistence stems from the words of my father." At that time, such books could only be safely read privately by individuals: "I felt like being alone on an island, it is a very lonely state".[18][19]

Reverence and fear of the universe is one of the main themes of Liu's writing. According to him, as humans we will stand in awe of the scale and depth of the universe. His novels also focus on curiosity about the unknown. Liu says he cannot help thinking about the future world and lifestyle of human beings, and he tries to invoke readers' curiosity with his books. He also believes that humans should be treated as an entirety.[20] Liu tried to answer the existential dilemma of "where should mankind go from here" through various efforts.[21]

Analysis

[edit]The book structure was originally influenced by concerns of Liu Cixin's Chinese publisher; the initial draft's opening scenes were seen as "too politically charged" by the publisher, and moved deeper into the book, to avoid attracting criticism by Chinese government censors.[22] Several interpretations of the novels and related film adaptations were presented by Ross Douthat of The New York Times in April 2024.[23]

Reception

[edit]

In December 2019, The New York Times cited The Three-Body Problem as having helped to popularize Chinese science fiction internationally, crediting the quality of Ken Liu's English translation, as well as endorsements of the book by George R. R. Martin, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, and former U.S. president Barack Obama.[15] George R. R. Martin wrote a blog about the novel, personally expressing its worthiness of the Hugo Award.[24] Obama said the book had "immense" scope, and that it was "fun to read, partly because my day-to-day problems with United States Congress seem fairly petty".[25]

Kirkus Reviews wrote that "in concept and development, it resembles top-notch Arthur C. Clarke or Larry Niven but with a perspective—plots, mysteries, conspiracies, murders, revelations and all—embedded in a culture and politic dramatically unfamiliar to most readers in the West, conveniently illuminated with footnotes courtesy of translator Liu."[26] Joshua Rothman of The New Yorker also called Liu Cixin "China's Arthur C. Clarke", and similarly observed that in "American science fiction ... humanity's imagined future often looks a lot like America's past. For an American reader, one of the pleasures of reading Liu is that his stories draw on entirely different resources", citing his use of themes relating to Chinese history and politics.[27]

Matthew A. Morrison wrote that the novel could "evoke a response all but unique to the genre: an awe at nature and the universe [which] SF readers call a 'sense of wonder'".

American streaming service Netflix announced in 2020 that Game of Thrones writers David Benioff and D. B. Weiss would be adapting the series into a sci-fi TV drama, making it one of the few originally non-English books adapted by Netflix. On the 18 June 2023, Netflix uploaded a teaser for the upcoming release.

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Awards | |

|---|---|

| 2006 Yinhe (Galaxy Award) | Won[3] |

| 2010 Chinese Fantasy Star Award for Best Novelette | Won[28] |

| 2015 Nebula Award for Best Novel | Nominated[29][30] |

| 2015 Hugo Award for Best Novel | Won[31] |

| 2015 John W. Campbell Memorial Award | Nominated[32] |

| 2015 Locus Award for Best SF Novel | Nominated[33] |

| 2015 Prometheus Award | Nominated[34] |

| 2015 John W. Campbell Memorial Award | Nominated[35] |

| 2017 Kurd-Laßwitz-Preis for Best Foreign SF work | Won[36] |

| 2017 Premio Ignotus for Foreign Novel | Won[37] |

| 2017 Grand Prix de l'Imaginaire for Foreign Novel | Nominated[38] |

| 2018 Premio Italia Award for Best International Novel | Won[39] |

| 2018 Arthur C. Clarke Award for Imagination in Service to Society | Won[40] |

| 2019 Booklog Award for Best Translated Novel | Won[41] |

| 2020 Seiun Award for Best Translated Novel | Won[42] |

Adaptations

[edit]Film

[edit]- The Three-Body Problem is a postponed Chinese science fiction 3D film[43] directed by Fanfan Zhang and starring Feng Shaofeng and Zhang Jingchu. Filming began, but it was never completed or released.[44][45][46]

Comics

[edit]- A serialized digital comic adaptation has been published by Tencent Comics since 2019.[47]

Audio

[edit]- The audiobook adaptation of the Three Body Problem was produced by Macmillan in 2014 and narrated by Luke Daniels. It was released again in 2023 and narrated by Rosalind Chao, who starred in Netflix's TV adaptation.[48]

- The chapters of the Three Body Problem were featured in the serialized podcast Stories From Among the Stars produced by Tor Books and Macmillan in July 2021.[49]

- All three books of Remembrance of Earth's Past trilogy have been adapted into a 100-episode Mandarin radio drama on Ximalaya.[50][51]

Animation

[edit]- The Three-Body Problem in Minecraft is a fan-made (later officially-sanctioned) animated adaptation of the series, directed by Shenyou (Zhenyi Li). It was initially animated entirely as an amateur Minecraft machinima, with a low budget and production quality for its first season in 2014. According to Xu Yao, the CEO of The Three-Body Universe, Shenyou chose this medium out of the minimal budget, as Minecraft allows its players to design environments with ease and does not require animation. The machinima format, after the first season's first few episodes, was later converted into Minecraft-styled computer animation due to the show's success.[52][53]

Television

[edit]- A Chinese TV adaptation produced by Tencent Video premiered on 16 January 2023.[54] In 2024, NBC aired the Chinese series on Peacock, its streaming service, premiering on 10 February.[55]

- An American TV series based on the book was released by Netflix on 21 March 2024, with David Benioff, D.B. Weiss, and Alexander Woo writing and executive producing.[56][57]

- An award-winning documentary series titled Rendezvous with the Future, which explores the science behind Liu Cixin's science fiction, was produced by BBC Studios and released by Bilibili in China.[58][59] The first episode covers many ideas featured in The Three-Body Problem such as messaging extraterrestrial civilisations and the possibility of a gravitational wave transmitter.[58]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In reality, Alpha Centauri A and B form a relatively stable binary star system, while Proxima Centauri roughly orbits A and B.

References

[edit]- ^ Liu, Cixin (May 7, 2014). "The Worst of All Possible Universes and the Best of All Possible Earths: Three Body and Chinese Science Fiction". Tor.com. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014. Retrieved May 8, 2014.

- ^ Yeung, Jessie. "Game of Thrones producers to adapt Chinese sci-fi 'The Three-Body Problem' for Netflix". CNN. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Clute, John. "Yinhe Award" Archived 2017-12-01 at the Wayback Machine, Science Fiction Encyclopedia, 3rd edition. Accessed November 21, 2017

- ^ Chen, Xihan (November 30, 2012). 《三体》选定英文版美国译者 [U.S. Translator Selected for English Version of 'Three Bodies'] (in Chinese). Xinhua. Archived from the original on March 1, 2013. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ "Three Body." Ken Liu Official Website. Retrieved on July 29, 2015.

- ^ "2015 Hugo Award Winners Announced". The Hugo Awards. August 22, 2015. Archived from the original on August 24, 2015. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ^ Chen, Andrea. "Out of this world: Chinese sci-fi author Liu Cixin is Asia's first writer to win Hugo award for best novel." South China Morning Post. Monday 24 August 2015. Retrieved on 27 August 2015.

- ^ "The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu (Published by Tor) Nominated for Best Novel in 2014". Nebula Awards. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ 科幻作家刘慈欣工作调动 当地市委书记亲自过问_中国作家网. chinawriter.com.cn (in Chinese). Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- ^ Richardson, Nick (April 8, 2024). "Nick Richardson · Even what doesn't happen is epic: Chinese SF". London Review of Books. 40 (3). Archived from the original on April 8, 2024. Retrieved April 8, 2024.

- ^ Shu Yingwang (数英网). 刘慈欣与他的科幻创作. 数英 (in Chinese). Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ a b 刘慈欣《三体》从小众科幻走向大众 改编成电影作者成监制. takefoto.cn (in Chinese). Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- ^ 流浪地球,从科幻小说到电影的改变_科普中国网. kepuchina.cn (in Chinese). Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- ^ Jianqiao, Lei (October 17, 2010). "Welcome to the "Three-Body Epoch"". Nanfang Metropolis Daily (in Chinese).

- ^ a b c Alter, Alexandra (December 3, 2019). "How Chinese Sci-Fi Conquered America". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Tor.com (July 23, 2013). "Tor Books to Release The Three-Body Problem, the First Chinese Science Fiction Novel Translated Into English". Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "The Three Body Problem". Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Tang, Qiao. 刘慈欣与《三体》背后的故事 [Liu Cixin and the Story Behind 'The Three-Body Problem']. China Writers Association (in Chinese). Guangming Daily. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ Geng, Olivia; William, Kazer. "Writing China: Cixin Liu, 'The Three-Body Problem'". Wall Street Journal. No. 31 October 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ Yuan, Bo; Hu, Yongqiu (eds.). 想象力是什么?科幻作家刘慈欣这样说 [What is imagination? Sci-fi writer Liu Cixin says so]. People's Daily (in Chinese). Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ 西方读者对刘慈欣《三体》三部曲零道德宇宙的审美接受-知网文化 [Western Readers' Aesthetic Reception of the Zero Moral Universe in Liu Cixin's Three Bodies Trilogy]. wh.cnki.net (in Chinese). Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ Alter, Alexandra (December 3, 2019). "How Chinese Sci-Fi Conquered America". The New York Times.

- ^ Douthat, Ross (April 12, 2024). "Three Interpretations of 'The Three-Body Problem'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 12, 2024. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ grrm (May 3, 2015). "Reading for Hugos". Not A Blog. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Kakutani, Michiko (January 16, 2017). "Obama's Secret to Surviving the White House Years: Books". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ "The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu". Kirkus Reviews. October 15, 2014.

- ^ Rothman, Joshua (March 6, 2015). "Liu Cixin is China's Answer to Arthur C. Clarke". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ 中国科幻大事记(1891年至2017年)之四--科幻--中国作家网. chinawriter.com.cn (in Chinese). Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "Nebula Awards Nominees and Winners: Best Novel". Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "2014 Nebula Awards Nominees Announced". February 20, 2015. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ Kevin (August 23, 2015). "2015 Hugo Award Winners Announced". The Hugo Awards. Archived from the original on August 24, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ "The John W. Campbell Award". christopher-mckitterick.com. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "2015 Locus Awards Winners". Locus Online. June 27, 2015. Archived from the original on June 12, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ "2015 Prometheus Award Winner". Locus Online. July 13, 2015. Archived from the original on June 12, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ "2015 Campbell and Sturgeon Awards Winners". Locus Online. June 15, 2015. Archived from the original on June 12, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ "2017 Kurd Laßwitz Preis Winners". Locus Online. June 12, 2017. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ "2017 Premio Ignotus Winners". Locus Online. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ "Grand Prix de l'Imaginaire 2017 Winners". Locus Online. June 5, 2017. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ admin. "The 2018 SF&F Premio Italia (Italy Award)". Europa SF. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ Zhang, Yishuo (November 10, 2018). "The Three Body Problem Author Picks Up Arthur C. Clarke Award". Yicai Global. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ Jia, Mei (December 16, 2019). "Possibilities of mind and matter". China Daily. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ "2020 Seiun Awards Winners". Locus Online. August 24, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ^ 三体 的海报 (in Chinese). Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ^ 三体 (2017) (in Chinese). Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ^ 三体 (2017) (in Chinese). Mtime.com Inc. Archived from the original on February 7, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ^ "Premiere of Film based on Acclaimed Sci-fi Novel 'The Three-Body Problem' Pushed Back until 2017". June 23, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ Tantimedh, Adi (November 7, 2021). "The Three-Body Problem: Tencent Releases First TV Series Adapt Trailer". bleedingcool.

- ^ Pulliam-Moore, Charles (February 7, 2024). "The Three-Body Problem is getting a new audiobook release just in time for Netflix's show". The Verge.

- ^ Pulliam-Moore, Charles (July 14, 2021). "The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu Has Become a Serialized Podcast". GIZMODO.

- ^ Xinhua (January 21, 2022). "Finale of Chinese radio drama 'Three-Body' released". china.org.cn.

- ^ 三体(全六季). Ximalaya (in Chinese).

- ^ "How a Minecraft-Animated Three-Body Problem Show Became a Huge Hit". April 15, 2020.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (March 24, 2020). "'Three-Body Problem' Inspired Bilibili Anime Earns Rave Reviews". Anime Magazine.

- ^ "Tencent's live-action Three-Body Problem drama debuts to rave reviews". Tech Node. January 16, 2023.

- ^ Wei, Xu (February 7, 2024). "NBC to air Chinese sci-fi series 'Three-Body' on its streaming service". SHINE. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ "International best-seller 'The Three-Body Problem' to be adapted as a Netflix original series". Netflix Media Center. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ "3 Body Problem - Netflix Teaser Trailer". Youtube. June 17, 2023.

- ^ a b 未来漫游指南 [Rendezvous with the Future]. Bilibili (in Chinese). 2022.

- ^ "Rendezvous with the Future". Guangzhou International Documentary Film Festival. 2023.

External links

[edit]- Official website of Ken Liu

- The Three Body Problem title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- 2008 Chinese novels

- 2008 science fiction novels

- Science fiction novel trilogies

- Novels by Liu Cixin

- Novels about alien invasions

- Hugo Award for Best Novel–winning works

- Fiction set around Alpha Centauri

- Novels about the Cultural Revolution

- Chinese novels adapted into films

- Chinese novels adapted into television series

- Works originally published in Chinese magazines

- Search for extraterrestrial intelligence in literature

- Tor Books books

- Head of Zeus books

- Hard science fiction

- Science fiction about first contact