The Big Lebowski

| The Big Lebowski | |

|---|---|

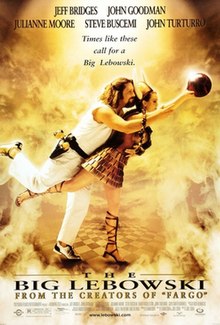

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Joel Coen |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Ethan Coen |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Roger Deakins |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Carter Burwell |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 117 minutes |

| Countries | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million |

| Box office | $47.4 million[4] |

The Big Lebowski (/ləˈbaʊski/) is a 1998 crime comedy film written, directed, produced and co-edited by Joel and Ethan Coen. It follows the life of Jeffrey "The Dude" Lebowski (Jeff Bridges), a Los Angeles slacker and avid bowler. He is assaulted as a result of mistaken identity then learns that a millionaire, also named Jeffrey Lebowski (David Huddleston), was the intended victim. The millionaire Lebowski's trophy wife is supposedly kidnapped and millionaire Lebowski commissions The Dude to deliver the ransom to secure her release. The plan goes awry when the Dude's friend Walter Sobchak (John Goodman) schemes to keep the ransom money for the Dude and himself. Sam Elliott, Julianne Moore, Steve Buscemi, John Turturro, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Tara Reid, David Thewlis, Peter Stormare, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Jon Polito and Ben Gazzara also appear in supporting roles.

The film is loosely inspired by the work of Raymond Chandler. Joel Coen stated, "We wanted to do a Chandler kind of story – how it moves episodically and deals with the characters trying to unravel a mystery, as well as having a hopelessly complex plot that's ultimately unimportant."[5] The original score was composed by Carter Burwell, a longtime collaborator of the Coen brothers.

The Big Lebowski received mixed reviews at the time of its release. Reviews have since become largely positive and the film has become a cult favorite, noted for its eccentric characters, comedic dream sequences, idiosyncratic dialogue and eclectic soundtrack.[6][7] In 2014, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant."

Plot

[edit]In 1990 or 1991,[8][9] slacker and avid bowler Jeffrey "The Dude" Lebowski is attacked in his Los Angeles home by two enforcers for porn kingpin Jackie Treehorn, to whom a different Jeffrey Lebowski's wife owes money. One enforcer urinates on the Dude's rug before the two realize they have the wrong man and leave.

After consulting his bowling partners, Vietnam veteran Walter Sobchak and Donny Kerabatsos, the Dude visits wealthy philanthropist Jeffrey Lebowski ("the big Lebowski"), requesting compensation for the rug. Lebowski refuses but the Dude tricks his assistant Brandt into letting him take a similar rug from the mansion. Outside, he meets Bunny, Lebowski's trophy wife and her German nihilist friend Uli. Soon afterward, Bunny is apparently kidnapped and Lebowski hires the Dude to deliver a ransom. That night, another group of thugs ambushes the Dude, taking his replacement rug on behalf of Lebowski's daughter Maude, who has a sentimental attachment to it.

Convinced the kidnap was a ruse by Bunny, Walter fakes the ransom drop. He and the Dude return to the bowling alley, leaving the briefcase of money in the Dude's car trunk. While they are bowling, the car is stolen. The Dude is confronted by Lebowski, who has an envelope from the kidnappers containing a severed toe, supposedly Bunny's. Maude asks the Dude to help recover the money her father illegally withdrew from the family's charity foundation.

The police recover the Dude's car. The briefcase is missing but the Dude finds a clue: a sheet of homework signed by a teenager named Larry Sellers. Walter learns that Larry is the good-for-nothing son of Arthur Digby Sellers, a principal writer for the television show Branded, that Walter reveres. The Dude and Walter visit Larry but get no information from him, as Larry remains mute and affectless through Walter's increasingly volatile and obscene interrogation. Walter assumes a sports car in front of Larry's house was purchased with the ransom and smashes it. The car actually belongs to a neighbor, who smashes the Dude's car in return.

Jackie Treehorn's thugs abduct the Dude and bring him to the porn kingpin, who demands to know where Bunny is and what happened to his money. The Dude says Bunny faked her kidnapping and Larry has the money then passes out from a spiked drink Treehorn gave him. He is arrested while wandering deliriously in Malibu and evicted by the police chief. On his way home Bunny (whose toes are intact) drives by, unnoticed by the Dude.

Maude is waiting for the Dude at his home and has sex with him, wishing to become pregnant by a father with whom she will not have to interact. She tells the Dude that her father has no money of his own; he is dependent on an allowance that Maude gives him from her inheritance from her late mother.

The Dude and Walter confront Lebowski and find Bunny has returned, having simply gone out of town without telling anyone. Bunny's nihilist friends took the opportunity to blackmail Lebowski, who in turn, had tried to embezzle money from the family charity, blaming its disappearance on the blackmailers. The Dude believes the briefcase never contained any money. An enraged Walter suspects Lebowski is faking his paralysis and lifts him out of his wheelchair but his condition is real.

Walter and the Dude are bowling when a rival bowler, Jesus Quintana, interrupts them. Walter had previously stated that he could not bowl on Saturdays since he is shomer Shabbos. In a tirade, Quintana implies he does not believe Walter's excuse for not bowling on Saturday, threatens Walter and the Dude and storms out. Outside the bowling alley, the nihilists set fire to the Dude's car and demand the ransom money. Walter fights them off but Donny dies from a heart attack. On a cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean, Walter eulogizes Donny's passing, but ultimately ruins it by unrelatedly referring to his fallen comrades in Vietnam. As he scatters Donny's ashes, they are blown back onto the Dude by an ill-timed updraft. As Walter tries to brush off the ashes, the Dude finally loses his temper and yells at him for everything that has happened. After apologizing and consoling the Dude, the two go bowling.

At the bowling alley, the Dude encounters the Stranger, the movie's narrator, who sums up everything that happened in the film and states that while he "didn't like seeing Donny go", he remains inspired by the Dude and that Maude is pregnant with a "little Lebowski on the way."

Cast

[edit]- Jeff Bridges as Jeffrey "The Dude" Lebowski

- John Goodman as Walter Sobchak

- Julianne Moore as Maude Lebowski

- Steve Buscemi as Donny Kerabatsos

- David Huddleston as Jeffrey "The Big" Lebowski

- Philip Seymour Hoffman as Brandt

- Tara Reid as Bunny Lebowski

- John Turturro as Jesus Quintana

- Sam Elliott as The Stranger

- David Thewlis as Knox Harrington

- Ben Gazzara as Jackie Treehorn

- Peter Stormare, Torsten Voges, and Flea as Uli Kunkel/Karl Hungus, Franz, and Kieffer, the nihilists

- Jon Polito as Da Fino

- Philip Moon and Mark Pellegrino as Treehorn's thugs

- Jimmie Dale Gilmore as Smokey

- Jack Kehler as Marty, The Dude's landlord

- Dom Irrera as Tony, the chauffeur

- Harry Bugin as Arthur Digby Sellers

- Jesse Flanagan as Larry Sellers

- Leon Russom as the Malibu Police Chief

- Warren Keith as Francis Donnelly, funeral director

- Marshall Manesh as Doctor

- Asia Carrera as Sherry, porn actress[10]

- Aimee Mann as Franz's girlfriend

- Richard Gant and Christian Clemenson as cops

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]The Dude is mostly inspired by Jeff Dowd, an American film producer and political activist the Coen brothers met while they were trying to find distribution for their first feature, Blood Simple.[11]: 90 [12] Dowd had been a member of the Seattle Seven, liked to drink white Russians, and was known as "The Dude".[11]: 91–92 The Dude was also partly based on a friend of the Coen brothers, Peter Exline (now a member of the faculty at USC's School of Cinematic Arts), a Vietnam War veteran who reportedly lived in a dump of an apartment and was proud of a little rug that "tied the room together".[13]: 188 Exline knew Barry Sonnenfeld from New York University and Sonnenfeld introduced Exline to the Coen brothers while they were trying to raise money for Blood Simple.[11]: 97–98 Exline became friends with the Coens and in 1989, told them many stories from his own life, including some about his actor-writer friend Lewis Abernathy (one of the inspirations for Walter), a fellow Vietnam vet who later became a private investigator and helped him track down and confront a high school kid who stole his car.[11]: 99 As in the film, Exline's car was impounded by the Los Angeles Police Department and Abernathy found an 8th grader's homework under the passenger seat.[11]: 100

Exline also belonged to an amateur softball league but the Coens changed it to bowling in the film, because "it's a very social sport where you can sit around and drink and smoke while engaging in inane conversation".[13]: 195 The Coens met filmmaker John Milius when they were in Los Angeles making Barton Fink and incorporated his love of guns and the military into the character of Walter.[13]: 189 Milius introduced the Coen Brothers to one of his best friends, Jim Ganzer, who also served as a source for creating Jeff Bridges' character.[14] Also known as the Dude,[15] Ganzer and his gang, typical Malibu surfers, served as inspiration as well for Milius's film Big Wednesday.[16]

Before David Huddleston was cast as "Big" Jeffrey Lebowski, the Coens considered Robert Duvall (who did not like the script), Anthony Hopkins (who was not interested in playing an American), Gene Hackman (who was taking a break from acting at the time), Jack Nicholson (who was not interested, he only wanted to portray Moses), Tommy Lee Jones (who was considered "too young"), Ned Beatty, Michael Caine, Bruce Dern, James Coburn, Charles Durning, Jackie Cooper, Fred Ward, Richard Mulligan, Rod Steiger, Peter Boyle, Lloyd Bridges, Paul Dooley, Pat Hingle, Jonathan Winters, Norman Mailer, George C. Scott, Jerry Falwell, Gore Vidal, Andy Griffith, William F. Buckley, and Ernest Borgnine; the Coens' top choice was Marlon Brando.[17] Charlize Theron was considered for the role of Bunny Lebowski.[18] David Cross auditioned for the role of Brandt.[19]

According to Julianne Moore, the character of Maude was based on artist Carolee Schneemann, "who worked naked from a swing", and on Yoko Ono.[20]: 156 The character of Jesus Quintana, a bowling opponent of The Dude's team, was inspired in part by a performance the Coens had seen John Turturro give in 1988 at the Public Theater in a play called Mi Puta Vida in which he played a pederast-type character, "so we thought, let's make Turturro a pederast. It'll be something he can really run with," Joel said in an interview.[13]: 195

The film's overall structure was influenced by the detective fiction of Raymond Chandler. Ethan said, "We wanted something that would generate a certain narrative feeling – like a modern Raymond Chandler story, and that's why it had to be set in Los Angeles ... We wanted to have a narrative flow, a story that moves like a Chandler book through different parts of town and different social classes."[21] The use of the Stranger's voice-over also came from Chandler as Joel remarked, "He is a little bit of an audience substitute. In the movie adaptation of Chandler it's the main character that speaks off-screen, but we didn't want to reproduce that though it obviously has echoes. It's as if someone was commenting on the plot from an all-seeing point of view. And at the same time rediscovering the old earthiness of a Mark Twain."[20]: 169

The significance of the bowling culture was, according to Joel, "important in reflecting that period at the end of the fifties and the beginning of the sixties. That suited the retro side of the movie, slightly anachronistic, which sent us back to a not-so-far-away era, but one that was well and truly gone nevertheless."[20]: 170

Screenplay

[edit]The Coen Brothers wrote The Big Lebowski around the same time as Barton Fink. When the Coen brothers wanted to make it, John Goodman was filming episodes for Roseanne and Jeff Bridges was making the Walter Hill film Wild Bill. The Coens decided to make Fargo in the meantime.[13]: 189 According to Ethan, "the movie was conceived as pivoting around that relationship between the Dude and Walter", which sprang from the scenes between Barton Fink and Charlie Meadows in Barton Fink.[20]: 169 They also came up with the idea of setting the film in contemporary L.A., because the people who inspired the story lived in the area.[22]: 41 When Pete Exline told them about the homework in a baggie incident, the Coens thought that that was very Raymond Chandler and decided to integrate elements of the author's fiction into their script. Joel Coen cites Robert Altman's The Long Goodbye as a primary influence on their film, in the sense that The Big Lebowski "is just kind of informed by Chandler around the edges".[22]: 43 When they started writing the script, the Coens wrote only 40 pages and then let it sit for a while before finishing it. This is a normal writing process for them, because they often "encounter a problem at a certain stage, we pass to another project, then we come back to the first script. That way we've already accumulated pieces for several future movies."[20]: 171 In order to liven up a scene that they thought was too heavy on exposition, they added an "effete art-world hanger-on", known as Knox Harrington, late in the screenwriting process.[23] In the original script, the Dude's car was a Chrysler LeBaron, as Dowd had once owned, but that car was not big enough to fit John Goodman so the Coens changed it to a Ford Torino.[11]: 93

Pre-production

[edit]PolyGram and Working Title Films, which had funded Fargo, backed The Big Lebowski with a budget of $15 million. In casting the film, Joel remarked, "we tend to write both for people we know and have worked with, and some parts without knowing who's going to play the role. In The Big Lebowski we did write for John [Goodman] and Steve [Buscemi], but we didn't know who was getting the Jeff Bridges role."[24] The Coens originally considered Mel Gibson for the role of The Dude, but he did not take the pitch too seriously.[25][26] Bridges was hesitant to play the role as he was worried that would be a bad example for his daughters, but his daughter Jessica convinced him to take it after a meeting.[27] In preparation for his role, Bridges met Dowd but actually "drew on myself a lot from back in the Sixties and Seventies. I lived in a little place like that and did drugs, although I think I was a little more creative than the Dude."[13]: 188 The actor went into his own closet with the film's wardrobe person and picked out clothes that he had thought the Dude might wear.[11]: 27 He wore his character's clothes home because most of them were his own.[28] The actor also adopted the same physicality as Dowd, including the slouching and his ample belly.[11]: 93 Originally, Goodman wanted a different kind of beard for Walter but the Coen brothers insisted on the "Gladiator" or what they called the "Chin Strap" and he thought it would go well with his flattop haircut.[11]: 32

For the film's look, the Coens wanted to avoid the usual retro 1960s clichés like lava lamps, Day-Glo posters, and Grateful Dead music[22]: 95 and for it to be "consistent with the whole bowling thing, we wanted to keep the movie pretty bright and poppy", Joel said in an interview.[13]: 191 For example, the star motif, featured predominantly throughout the film, started with the film's production designer Richard Heinrichs' design for the bowling alley. According to Joel, he "came up with the idea of just laying free-form neon stars on top of it and doing a similar free-form star thing on the interior". This carried over to the film's dream sequences. "Both dream sequences involve star patterns and are about lines radiating to a point. In the first dream sequence, the Dude gets knocked out and you see stars and they all coalesce into the overhead nightscape of L.A. The second dream sequence is an astral environment with a backdrop of stars", remembers Heinrichs.[13]: 191 For Jackie Treehorn's Malibu beach house, he was inspired by late 1950s and early 1960s bachelor pad furniture. The Coen brothers told Heinrichs that they wanted Treehorn's beach party to be Inca-themed, with a "very Hollywood-looking party in which young, oiled-down, fairly aggressive men walk around with appetizers and drinks. So there's a very sacrificial quality to it."[22]: 91

Cinematographer Roger Deakins discussed the look of the film with the Coens during pre-production. They told him that they wanted some parts of the film to have a real and contemporary feeling and other parts, like the dream sequences, to have a very stylized look.[22]: 77 Bill and Jacqui Landrum did all of the choreography for the film. For his dance sequence, Jack Kehler went through three three-hour rehearsals.[11]: 27 The Coen brothers offered him three to four choices of classical music for him to pick from and he chose Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition. At each rehearsal, he went through each phase of the piece.[11]: 64

Principal photography

[edit]Actual filming took place over an eleven-week period with location shooting in and around Los Angeles, including all of the bowling sequences at the Hollywood Star Lanes (for three weeks)[29] and the Dude's Busby Berkeley dream sequences in a converted airplane hangar.[21] According to Joel, the only time they ever directed Bridges "was when he would come over at the beginning of each scene and ask, 'Do you think the Dude burned one on the way over?' I'd reply 'Yes' usually, so Jeff would go over in the corner and start rubbing his eyes to get them bloodshot."[13]: 195 Julianne Moore was sent the script while working on The Lost World: Jurassic Park. She worked only two weeks on the film, early and late during the production that went from January to April 1997,[30] while Sam Elliott was only on set for two days and did many takes of his final speech.[11]: 46

Joel Coen said that Jeff Bridges was upset there was no playback monitor so Bridges made them get a playback monitor at the end of the second week of production.[31]

The scenes in Jackie Treehorn's house were shot in the Sheats-Goldstein Residence, designed by John Lautner and built in 1963 in the Hollywood Hills.[32]

Deakins described the look of the fantasy scenes as being very crisp, monochromatic, and highly lit in order to afford greater depth of focus. However, with the Dude's apartment, Deakins said, "it's kind of seedy and the light's pretty nasty" with a grittier look. The visual bridge between these two different looks was how he photographed the night scenes. Instead of adopting the usual blue moonlight or blue street lamp look, he used an orange sodium-light effect.[22]: 79 The Coen brothers shot much of the film with wide-angle lens because, according to Joel, it made it easier to hold focus for a greater depth and it made camera movements more dynamic.[22]: 82

To achieve the point-of-view of a rolling bowling ball the Coen brothers mounted a camera "on something like a barbecue spit", according to Ethan, and then dollied it along the lane. The challenge for them was figuring out the relative speeds of the forward motion and the rotating motion. CGI was used to create the vantage point of the thumb hole in the bowling ball.[30]

Soundtrack

[edit]| The Big Lebowski: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Various artists | ||||

| Released | February 24, 1998 | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 51:45 | |||

| Label | Mercury | |||

| Producer | T Bone Burnett, Joel Coen, Ethan Coen | |||

| Coen Brothers film soundtracks chronology | ||||

| ||||

The original score was composed by Carter Burwell, a veteran of all the Coen Brothers' films. While the Coens were writing the screenplay they had Kenny Rogers' "Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)", the Gipsy Kings' cover of "Hotel California", and several Creedence Clearwater Revival songs in mind.[33] They asked T Bone Burnett (who would later work with the Coens on O Brother, Where Art Thou? and Inside Llewyn Davis) to pick songs for the soundtrack of the film. They knew that they wanted different genres of music from different times but, as Joel remembers, "T Bone even came up with some far-out Henry Mancini and Yma Sumac."[34] Burnett was able to secure songs by Kenny Rogers and the Gipsy Kings and also added tracks by Captain Beefheart, Moondog and Bob Dylan's "The Man in Me".[33] However, he had a tough time securing the rights to Townes Van Zandt's cover of the Rolling Stones' "Dead Flowers", which plays over the film's closing credits. Former Stones manager Allen Klein owned the rights to the song and wanted $150,000 for it. Burnett convinced Klein to watch an early cut of the film and remembers, "It got to the part where the Dude says, 'I hate the fuckin' Eagles, man!' Klein stands up and says, 'That's it, you can have the song!' That was beautiful."[33][35][36] Burnett was going to be credited on the film as "Music Supervisor", but asked his credit to be "Music Archivist" because he "hated the notion of being a supervisor; I wouldn't want anyone to think of me as management".[34]

For Joel, "the original music, as with other elements of the movie, had to echo the retro sounds of the Sixties and early Seventies".[20]: 156 Music defines each character. For example, Bob Nolan's "Tumbling Tumbleweeds" was chosen for the Stranger at the time the Coens wrote the screenplay, as was Henry Mancini's "Lujon" by for Jackie Treehorn. "The German nihilists are accompanied by techno-pop and Jeff Bridges by Creedence. So there's a musical signature for each of them", remarked Ethan in an interview.[20]: 156 The character Uli Kunkel was in the German electronic band Autobahn, an homage to the band Kraftwerk. The album cover of their record Nagelbett (bed of nails) is a parody of the Kraftwerk album cover for The Man-Machine and the group name Autobahn shares the name of a Kraftwerk song and album. In the lyrics the phrase "We believe in nothing" is repeated with electronic distortion. This is a reference to Autobahn's nihilism in the film.[37]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Performer | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Tumbling Tumbleweeds" | Bob Nolan | Sons of the Pioneers | |

| 2. | "Mucha Muchacha" | Juan García Esquivel | Esquivel | |

| 3. | "I Hate You" | Gary Burger, David Havlicek, Roger Johnston, Thomas E. Shaw and Larry Spangler | The Monks | |

| 4. | "Requiem in D Minor: Introitus and Lacrimosa" | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | The Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir | |

| 5. | "Run Through the Jungle" | John Fogerty | Creedence Clearwater Revival | |

| 6. | "Behave Yourself" | Booker T. Jones, Steve Cropper, Al Jackson, Jr. and Lewie Steinberg | Booker T. & the MG's | |

| 7. | "Standing on the Corner" | Frank Loesser | Dean Martin | |

| 8. | "Tammy" | Jay Livingston and Ray Evans | Debbie Reynolds | |

| 9. | "We Venerate Thy Cross" | traditional | The Rustavi Choir | |

| 10. | "Lookin' Out My Back Door" | John Fogerty | Creedence Clearwater Revival | |

| 11. | "Gnomus" (from Pictures at an Exhibition) | Modest Mussorgsky, arranged for orchestra by Maurice Ravel. | ||

| 12. | "Oye Como Va" | Tito Puente | Santana | |

| 13. | "Piacere Sequence" | Teo Usuelli | Usuelli | |

| 14. | "Branded Theme Song" | Alan Alch and Dominic Frontiere | ||

| 15. | "Peaceful Easy Feeling" | Jack Tempchin | Eagles | |

| 16. | "Viva Las Vegas" | Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman | ZZ Top (with Bunny Lebowski); and Shawn Colvin (closing credits). | |

| 17. | "Dick on a Case" | Carter Burwell | Burwell |

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The Big Lebowski received its world premiere at the 1998 Sundance Film Festival on January 18, 1998, at the 1,300-capacity Eccles Theater. It was also screened at the 48th Berlin International Film Festival[38][39] before opening in the United States and Canada on March 6, 1998, in 1,207 theaters. It grossed $5.5 million on its opening weekend, finishing up with a gross of $18 million in the United States and Canada, just above its US$15 million budget. The film's worldwide gross outside of the US and Canada was $28.7 million, (including $2.6 million in the United Kingdom) bringing its worldwide gross to $46.7 million.[4][40]

Critical response

[edit]On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 80% based on 191 reviews, with an average score of 7.40/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "The Big Lebowski's shaggy dog story won't satisfy everybody, but those who abide will be treated to a rambling succession of comic delights, with Jeff Bridges' laconic performance really tying the movie together."[41] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, has assigned the film a score of 71 out of 100 based on reviews from 23 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[42] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B" on an A+ to F scale.[43]

Many critics and audiences have likened the film to a modern Western, while many others dispute this, or liken it to a crime novel that revolves around mistaken identity plot devices.[44] Peter Howell, in his review for the Toronto Star, wrote: "It's hard to believe that this is the work of a team that won an Oscar last year for the original screenplay of Fargo. There's a large amount of profanity in the movie, which seems a weak attempt to paper over dialogue gaps."[45] Howell revised his opinion in a later review, and in 2011 stated that "it may just be my favourite Coen Bros. film."[46]

Todd McCarthy in Variety magazine wrote: "One of the film's indisputable triumphs is its soundtrack, which mixes Carter Burwell's original score with classic pop tunes and some fabulous covers."[47] USA Today gave the film three out of four stars and felt that the Dude was "too passive a hero to sustain interest," but that there was "enough startling brilliance here to suggest that, just like the Dude, those smarty-pants Coens will abide."[48]

In his review for The Washington Post, Desson Howe praised the Coens and "their inspired, absurdist taste for weird, peculiar Americana – but a sort of neo-Americana that is entirely invented – the Coens have defined and mastered their own bizarre subgenre. No one does it like them and, it almost goes without saying, no one does it better."[49]

Janet Maslin praised Bridges' performance in her review for The New York Times: "Mr. Bridges finds a role so right for him that he seems never to have been anywhere else. Watch this performance to see shambling executed with nonchalant grace and a seemingly out-to-lunch character played with fine comic flair."[50] Andrew Sarris, in his review for the New York Observer, wrote: "The result is a lot of laughs and a feeling of awe toward the craftsmanship involved. I doubt that there'll be anything else like it the rest of this year."[51] In a five star review for Empire, Ian Nathan wrote: "For those who delight in the Coens' divinely abstract take on reality, this is pure nirvana" and "in a perfect world all movies would be made by the Coen brothers."[52] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three stars out of four, describing it as "weirdly engaging."[53] In a 2010 review, he raised his original score to four stars out of four and added the film to his "Great Movies" canon.[54]

However, Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote in the Chicago Reader: "To be sure, The Big Lebowski is packed with show-offy filmmaking and as a result is pretty entertaining. But insofar as it represents a moral position—and the Coens' relative styling of their figures invariably does—it's an elitist one, elevating salt-of-the-earth types like Bridges and Goodman ... over everyone else in the movie."[55] Dave Kehr, in his review for the Daily News, criticized the film's premise as a "tired idea, and it produces an episodic, unstrung film."[56] The Guardian criticized the film as "a bunch of ideas shoveled into a bag and allowed to spill out at random. The film is infuriating, and will win no prizes. But it does have some terrific jokes."[57]

Legacy

[edit]Since its original release, The Big Lebowski has become a cult classic.[7] Ardent fans of the film call themselves "achievers".[58][59] Steve Palopoli wrote about the film's emerging cult status in July 2002.[60] He first realized that the film had a cult following when he attended a midnight screening in 2000 at the New Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles and witnessed people quoting dialogue from the film to each other.[11]: 129 Soon after the article appeared, the programmer for a local midnight film series in Santa Cruz decided to screen The Big Lebowski and on the first weekend they had to turn away several hundred people. The theater held the film over for six weeks, which had never happened before.[11]: 130

An annual festival, Lebowski Fest, began in Louisville, Kentucky, United States, in 2002 with 150 fans showing up, and has since expanded to several other cities.[61] The festival's main event each year is a night of unlimited bowling with various contests including costume, trivia, hardest- and farthest-traveled contests. Held over a weekend, events typically include a pre-fest party with bands the night before the bowling event as well as a day-long outdoor party with bands, vendor booths and games. Various celebrities from the film have attended some of the events, including Jeff Bridges who attended the Los Angeles event.[61] The British equivalent, inspired by Lebowski Fest, is known as The Dude Abides and is held in London.[62]

Dudeism, a religion devoted largely to spreading the philosophy and lifestyle of the film's main character, was founded in 2005. Also known as The Church of the Latter-Day Dude (a name parody of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints), the organization has ordained over 220,000 "Dudeist Priests" all over the world via its website.[63]

"The Big Lebowski and Philosophy: Keeping Your Mind Limber with Abiding Wisdom," published in 2012 by Wiley,[64] is a collection of 18 essays by different writers analyzing the movie's philosophical themes of nihilism, war and politics, money and materialism, idealism and morality, and the Dude as the philosopher's hero who struggles to live the good life in spite of the challenges he endures.

Two species of African spider are named after the film and main character: Anelosimus biglebowski and Anelosimus dude, both described in 2006.[65] Additionally, an extinct Permian conifer genus is named after the film in honor of its creators. The first species described within this genus in 2007 is based on 270-million-year-old plant fossils from Texas, and is called Lebowskia grandifolia.[66]

Entertainment Weekly ranked it 8th on their Funniest Movies of the Past 25 Years list.[67] The film was also ranked No. 34 on their list of "The Top 50 Cult Films"[68] and ranked No. 15 on the magazine's "The Cult 25: The Essential Left-Field Movie Hits Since '83" list.[69] In addition, the magazine also ranked The Dude No. 14 in their "The 100 Greatest Characters of the Last 20 Years" poll.[70] The film was also nominated for the prestigious Grand Prix of the Belgian Film Critics Association.[71] The Big Lebowski was voted as the 10th best film set in Los Angeles in the last 25 years by a group of Los Angeles Times writers and editors with two criteria: "The movie had to communicate some inherent truth about the L.A. experience, and only one film per director was allowed on the list."[72] Empire magazine ranked Walter Sobchak No. 49 and the Dude No. 7 in their "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters" poll.[73] Roger Ebert added The Big Lebowski to his list of "Great Movies" in March 2010.[54]

Spin-off

[edit]The Coen brothers have stated that they will never make a sequel to The Big Lebowski.[74] Nevertheless, John Turturro expressed interest in reprising his role as Jesus Quintana,[75] and in 2014, he announced that he had requested permission to use the character.[76] In August 2016, it was reported that Turturro would reprise his role as Jesus Quintana in The Jesus Rolls, a spin-off of The Big Lebowski, based on the 1974 French film Going Places, with Turturro starring, writing, and directing. It was released in 2020.[77] The Coen brothers, although having granted Turturro the right to use the character, were not involved, and no other character from The Big Lebowski was featured in the film.[78]

Stella Artois commercial

[edit]On January 24, 2019, Jeff Bridges posted a 5-second clip on Twitter with the statement: "Can't be living in the past, man. Stay tuned" and showing Bridges as the Dude, walking through a room as a tumbleweed rolls by.[79] The clip was a teaser trailer for an ad during Super Bowl LIII which featured Bridges reprising the role of The Dude for a Stella Artois commercial.[80][81]

Use as social and political analysis

[edit]The film has been used as a tool for analysis on a number of issues. In September 2008, Slate published an article that interpreted The Big Lebowski as a political critique. The center piece of this viewpoint was that Walter Sobchak is "a neocon," citing the film's references to then President George H. W. Bush and the first Gulf War.[82] The article says Sobchak's aggressive and impulsive attitude, which always results in catastrophe, is an allegory of neoconservative foreign policy and its supposed consequences.

A journal article by Brian Wall, published in the feminist journal Camera Obscura, uses the film to explain Karl Marx's commodity fetishism and the feminist consequences of sexual fetishism.[83]

In That Rug Really Tied the Room Together, first published in 2001, Joseph Natoli argues that The Dude represents a counter narrative to the post-Reaganomic entrepreneurial rush for "return on investment" on display in such films as Jerry Maguire and Forrest Gump.[84][85][86]

The movie has been used as a carnivalesque critique of society, as an analysis on war and ethics, as a narrative on mass communication and US militarism and other issues.[87][88][89]

Home media

[edit]Universal Studios Home Entertainment released a "Collector's Edition" DVD on October 18, 2005, with extra features that included an "introduction by Mortimer Young", "Jeff Bridges' Photography", "Making of The Big Lebowski", and "Production Notes". In addition, a limited-edition "Achiever's Edition Gift Set" also included The Big Lebowski Bowling Shammy Towel, four Collectible Coasters that included photographs and quotable lines from the film, and eight Exclusive Photo Cards from Jeff Bridges' personal collection.[90] A "10th Anniversary Edition" was released on September 9, 2008, and features all of the extras from the "Collector's Edition" and "The Dude's Life: Strikes and Gutters ... Ups and Downs ... The Dude Abides" theatrical trailer (from the first DVD release), "The Lebowski Fest: An Achiever's Story", "Flying Carpets and Bowling Pin Dreams: The Dream Sequences of the Dude", "Interactive Map", "Jeff Bridges Photo Book", and a "Photo Gallery". There are both a standard release and a Limited Edition which features "Bowling Ball Packaging" and is individually numbered.[91]

A high-definition version of The Big Lebowski was released by Universal on HD DVD format on June 26, 2007. The film was released in Blu-ray format in Italy by Cecchi Gori.

On August 16, 2011, Universal Pictures released The Big Lebowski on Blu-ray. The limited-edition package includes a Jeff Bridges photo book, a ten-years-on retrospective, and an in-depth look at the annual Lebowski Fest.[92] The film is also available in the Blu-ray Coen Brothers box set released in the UK; however, this version is region-free and will work in any Blu-ray player.

For the film's 20th Anniversary, Universal Pictures released a 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray version of the film, which was released on October 16, 2018.[93]

See also

[edit]- List of cult films

- List of films that most frequently use the word fuck

- List of films featuring fictional films

- List of films featuring miniature people

Notes

[edit]- ^ Roderick Jaynes is the shared pseudonym used by the Coen brothers for their editing.

References

[edit]- ^ "The Big Lebowski". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ a b "The Big Lebowski". Lumiere. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ "The Big Lebowski". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Big Lebowski (1998)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ Stone, Doug (March 9, 1998). "The Coens Speak (Reluctantly)". Indie Wire. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ^ Tobias, Scott. "The New Cult Canon – The Big Lebowski". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ a b Russell, Will (August 15, 2007). "The Big Lebowski: Hey Dude". The Independent. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ Orr, Christopher (September 16, 2014). "30 Years of Coens: The Big Lebowski". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on October 30, 2023. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ Allen, William Rodney (2006). The Coen Brothers - Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. p. 88. ISBN 9781578068890. Archived from the original on November 1, 2023. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ Van Luling, Todd (April 20, 2015). "5 Stories You Didn't Know About 'The Big Lebowski'". HuffPost. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Green, Bill; Ben Peskoe; Will Russell; Scott Shuffitt (2007). "I'm A Lebowski, You're A Lebowski". Bloomsbury.

- ^ Boardman, Madeline (March 6, 2013). "Jeff Dowd, Real 'Big Lebowski' Dude, Talks White Russians, Jeff Bridges And Bowling". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bergan, Ronald (2000). "The Coen Brothers". Thunder's Mouth Press.

- ^ Chu, Christie (January 23, 2015). "The Quest for Ed Ruscha's Rocky II – artnet News". artnet News. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ "The Real Dude: An Interview with Jim 'Jimmy'Z' Ganzer". openingceremony.us. Archived from the original on May 13, 2015. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ Bleakley, Sam; Callahan, J. S. (2012). Surfing Tropical Beats. Alison Hodge Publishers. p. 133. ISBN 978-0906720851. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ "Our friend Alex Belth just released The Dudes..." cinearchive.org. March 15, 2015. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015.

- ^ "The Big Lebowski: 50 facts you (probably) didn't know – Shortlist". August 6, 2021. Archived from the original on July 21, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Sellers, John (November 3, 2010). "David Cross on All His Roles: Mr. Show, Arrested Development, and More". Vulture. Archived from the original on October 2, 2023. Retrieved September 23, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ciment, Michel; Hubert Niogret (May 1998). "The Logic of Soft Drugs". Postif.

- ^ a b Levine, Josh (2000). "The Coen Brothers: The Story of Two American Filmmakers". ECW Press. p. 140.

- ^ a b c d e f g Robertson, William Preston; Tricia Cooke (1998). "The Big Lebowski: The Making of a Coen Brothers Film". W.W. Norton. p. 41.

- ^ McCarthy, Phillip (March 27, 1998). "Coen Off". Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Woods, Paul A (2000). "Joel & Ethan Coen: Blood Siblings". Plexus.

- ^ Greene, Andy (September 4, 2008). "'The Big Lebowski': The Decade of the Dude". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Patrick (March 7, 2018). "'The Dude abides': 20 years on, how the Big Lebowski became a cultural phenomenon". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- ^ "Jeff Bridges: Super Natural". Archived from the original on October 30, 2023. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ Carr, Jay (March 1, 1998). "The Big Easy". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Wloszcyna, Susan (March 5, 1998). "Another Quirky Coen Toss Turning Their Sly Style to Lebowski". USA Today.

- ^ a b Arnold, Gary (March 6, 1998). "Siblings' Style Has No Rivals". Washington Times.

- ^ "Coen Bros. Made a Filmmaking Exception After 'Big Lebowski' Set Made Jeff Bridges 'Miserable'". August 3, 2020. Archived from the original on June 20, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Movies featuring Lautner buildings". The John Lautner Foundation. April 12, 2008. Archived from the original on June 13, 2013. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ a b c Greene, Andy (September 4, 2008). "Inside the Dude's Stoner Soundtrack". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- ^ a b Altman, Billy (February 24, 2002). "A Music Maker Happy to Be Just a Conduit". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

- ^ "The Big Lebowski // Dead Flowers – Rollo & Grady: Los Angeles Music Blog". Rollogrady.com. August 29, 2008. Archived from the original on June 6, 2013. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ "Connection between The Rolling Stones and 'The Big Lebowski'". faroutmagazine.co.uk. December 29, 2021. Archived from the original on March 29, 2023. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "Projects – The Big Lebowski". Carterburwell.com. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- ^ "Berlinale: 1998 Programme". berlinale.de. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ "Berlinale 1998: Pix in official selection". Variety. February 9–15, 1998.

- ^ Scott, Mary (September 22, 2000). "Coen Brothers' films in the UK 1990-2000". Screen International. p. 39.

- ^ "The Big Lebowski (1998)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

- ^ "The Big Lebowski (1998)". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ "CinemaScore". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ Comentale, Edward P.; Jaffe, Aaron (2009). The Year's Work in Lebowski Studies By Edward P. Comentale, Aaron Jaffe p.230. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-22136-0. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ Howell, Peter (January 19, 1998). "Coens' latest doesn't hold together The Big Lebowski is more sprawling than large". Toronto Star.

- ^ Howell, Peter (July 7, 2011). "Howell: I love The Big Lebowski – even though the Wikipedia says I don't". The Star. Toronto Star Newspapers. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (January 20, 1998). "The Big Lebowski". Variety. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- ^ Wloszczyna, Susan (March 6, 1998). "The Big Lebowski: Coen humor to spare". USA Today.

- ^ Howe, Desson (March 6, 1998). "The Big Lebowski: Rollin' a Strike". The Washington Post.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (March 6, 1998). "A Bowling Ball's-Eye View of Reality". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- ^ Sarris, Andrew (March 8, 1998). "A Cubist Coen Comedy". New York Observer. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- ^ Nathan, Ian (May 1998). "The Big Lebowski". Empire. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2009.

- ^ "The Big Lebowski". Roger Ebert. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014. Retrieved March 28, 2010.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (March 10, 2010). "El Duderino in his time and place". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on March 22, 2010. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (March 6, 1998). "L.A. Residential". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (March 6, 1998). "Coen Brothers' Latest is a Big Letdownski". Daily News.

- ^ "Meanwhile, The Big Lebowski should have stayed in the bowling alley ...". The Guardian. April 24, 1998.

- ^ Larsen, Peter (March 21, 2013). "Bringing the bowling to 'The Big Lebowski'". The Orange County Register. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ Timberg, Scott (July 30, 2009). "'The Achievers: The Story of the Lebowski Fans' explores The Dude phenomenon". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ Palopoli, Steve (July 25–31, 2002). "The Last Cult Picture Show". Metro Santa Cruz. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ a b Hoggard, Liz (July 22, 2007). "Get with the Dude's vibe". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 14, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- ^ Hodgkinson, Will (May 11, 2005). "Dude, let's go bowling". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 27, 2006. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- ^ Anderman, Joan (September 15, 2009). "How 'The Big Lebowski' became a cultural touchstone and the impetus for festivals across the country". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- ^ Fosl, Peter; Irwin, William (2012). The Big Lebowski and Philosophy: Keeping Your Mind Limber with Abiding Wisdom. Wiley. p. 304. ISBN 978-1118074565.

- ^ Agnarsson, Ingi; Zhang, Jun-Xia. "New species of Anelosimus (Araneae: Theridiidae) from Africa and Southeast Asia, with notes on sociality and color polymorphism" (PDF). Zootaxa. 1147: 8, 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ Looy, Cindy V. (July 1, 2007). "Extending the Range of Derived Late Paleozoic Conifers: Lebowskia gen. nov. (Majonicaceae)". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 168 (6): 957–972. doi:10.1086/518256. ISSN 1058-5893. S2CID 84273509.

- ^ "The Comedy 25: The Funniest Movies of the Past 25 Years". Entertainment Weekly. August 27, 2008. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ "The Top 50 Cult Films". Entertainment Weekly. May 23, 2003.

- ^ "The Cult 25: The Essential Left-Field Movie Hits Since '83". Entertainment Weekly. September 3, 2008. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Characters of the Last 20 Years". Entertainment Weekly. June 4–11, 2010. p. 64.

- ^ ""Hana Bi": grand prix U.C.C." Le Soir (in French). January 12, 1999. p. 10. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (August 31, 2008). "L.A.'s story is complicated, but they got it: The 25 best L.A. films of the last 25 years". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 8, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters". Empire. Archived from the original on September 6, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2008.

- ^ Setoodeh, Ramin (February 3, 2016). "The Coen Brothers Will Never Make a Sequel to 'The Big Lebowski'". Variety. Archived from the original on September 5, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ O'Neal, Sean (June 28, 2011). "Random Roles: John Turturro". The A.V. Club'. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Lyman, Eric J. (June 22, 2014). "Taormina Fest Honors John Turturro, Fox's Jim Gianopulos on Final Day". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 25, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (July 8, 2019). "The Big Release Date: John Turturro's 'The Jesus Rolls' To Hit Theaters In 2020". Deadline. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ McNary, Dave (August 18, 2016). "John Turturro in Production on 'Big Lebowski' Spinoff 'Going Places'". Variety. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Kirkland, Justin (January 24, 2019). "The Dude Returns in an Ad That Will Really Tie Super Bowl Sunday Together". Esquire. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Jordan Laskey, Mike (January 31, 2019). "Don't let that 'Big Lebowski' Super Bowl commercial delight you". National Catholic Reporter. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

At the end of the clip, the date "2.3.19" appears. "A sequel! And it's coming out in like 10 days!" I immediately thought. But then I remembered the American liturgical calendar: Feb. 3 is the Super Bowl. This couldn't be as good as it seemed.

- ^ E. J. Schultz (January 28, 2019). "Stella Artois Reprises 'The Big Lebowski' and 'Sex and the City' in Super Bowl Ad". Ad Age. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ Haglund, David (September 11, 2008). "Walter Sobchak, Neocon". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on December 25, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ Wall, Brian 2008, "'Jackie Treehorn Treats Objects Like Women!': Two Types of Fetishism in The Big Lebowski," Camera Obscura,, Vol. 23 No. 3, pp. 111–135

- ^ Natoli, Joseph (2001). Postmodern Journeys: Film and Culture 1996–1998. SUNY.

- ^ Oliver Benjamin, ed. (2013). Lebowski 101:Limber-Minded Investigations into the Greatest Story Ever Blathered. Abide University Press.

- ^ Natoli, Joseph (2017). Dark Affinities, Dark Imaginaries: A Mind's Odyssey. SUNY Press.

- ^ Martin, Paul; Renegar, Valeria (2007). ""The Man for His Time" The Big Lebowski as Carnivalesque Social Critique". Communication Studies. 58 (3): 299–313. doi:10.1080/10510970701518397. S2CID 144179844.

- ^ ""This Aggression Will Not Stand": Myth, War, and Ethics in The Big Lebowski". Sub.uwpress.org. January 1, 2005. Archived from the original on November 24, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2012.

- ^ Martin-Jones, David (September 18, 2006). "Part Three Representing Automobility: No literal connection: images of mass commodification, US militarism, and the oil industry, in The Big Lebowski". The Sociological Review. 54: 133–149. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2006.00641.x. S2CID 141887692.

- ^ Foster, Dave (August 27, 2005). "The Big Lebowski CE in October". DVD Times. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ Foster, Dave (April 6, 2008). "The Big Lebowski 10th AE (R1) in September". DVD Times. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ Matheson, Whitney (August 16, 2011). "Cool stuff on DVD today: 'Lebowski' on Blu-ray!". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved August 16, 2011.

- ^ "4K Review on Blu-ray Authority". October 19, 2018. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Bergan, Ronald, The Coen Brothers (2000, Thunder's Mouth Press), ISBN 1-56025-254-5.

- Coen, Ethan and Joel Coen, The Big Lebowski (May 1998, Faber and Faber Ltd.), ISBN 0-571-19335-8.

- Green, Bill, Ben Peskoe, Scott Shuffitt, Will Russell; I'm a Lebowski, You're a Lebowski: Life, The Big Lebowski, and What Have You (Bloomsbury USA – August 21, 2007), ISBN 978-1-59691-246-5.

- Levine, Josh, The Coen Brothers: The Story of Two American Filmmakers, (2000, ECW Press), ISBN 1-55022-424-7.

- Robertson, William Preston, Tricia Cooke, John Todd Anderson and Rafael Sanudo, The Big Lebowski: The Making of a Coen Brothers Film (1998, W.W. Norton & Company), ISBN 0-393-31750-1.

- Rohrer, Finlo (October 10, 2008). "Is The Big Lebowski a cultural milestone?". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- Tyree, J. M., Ben Walters The Big Lebowski (BFI Film Classics, 2007, British Film Institute), ISBN 978-1-84457-173-4.

- The Big Lebowski in Feminist Film Theory

- The Big Lebowski essay by J.M. Tyree & Ben Walters at National Film Registry

- "Dissertations on His Dudeness", Dwight Garner, The New York Times, December 29, 2009

- Comentale, Edward P. and Aaron Jaffe, eds. The Year's Work in Lebowski Studies. Bloomington: 2009.

- "Deception and detection: The Trickster Archetype in the film, The Big Lebowski, and its cult following" in Trickster's Way

External links

[edit]- 1998 films

- The Big Lebowski

- 1990s American films

- 1990s British films

- 1990s buddy comedy films

- 1998 crime comedy films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1998 independent films

- Albums produced by T Bone Burnett

- American buddy comedy films

- American crime comedy films

- American independent films

- American neo-noir films

- British crime comedy films

- British independent films

- British neo-noir films

- Comedy film soundtracks

- Cultural depictions of Saddam Hussein

- English-language crime comedy films

- Fiction about unemployment

- Films about kidnapping in the United States

- Films directed by the Coen brothers

- Films scored by Carter Burwell

- Films set in 1991

- Films set in a theatre

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films set in Malibu, California

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films with screenplays by the Coen brothers

- Gramercy Pictures films

- Mercury Records soundtracks

- PolyGram Filmed Entertainment films

- Postmodern films

- Stoner crime films

- Ten-pin bowling films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Universal Pictures films

- Working Title Films films

- English-language independent films

- English-language buddy comedy films