WEHI

| |

| Latin: Fiat Lux | |

| Motto | Brighter together |

|---|---|

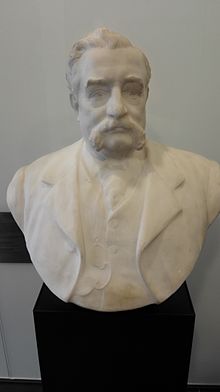

| Founder | Harry Brookes Allen |

| Established | 1915 |

| Mission | Translational medical research |

| President | Christopher Thomas |

| Director | Doug Hilton AO, FAA |

| Faculty | University of Melbourne |

| Adjunct faculty | Royal Melbourne Hospital |

| Staff | approx. 1,000 (incl. 166 students) |

| Budget | A$105 million (2015) |

| Formerly called | Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research |

| Location | , , , Australia |

| Coordinates | 37°47′53″S 144°57′22″E / 37.798°S 144.956°E |

| Website | www |

| [1] | |

WEHI (English: /wiːˈhaɪ/), previously known as the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, and as the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, is Australia's oldest medical research institute.[2] Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet, who won the Nobel Prize in 1960 for his work in immunology, was director from 1944 to 1965. Burnet developed the ideas of clonal selection and acquired immune tolerance. Later, Professor Donald Metcalf discovered and characterised colony-stimulating factors. As of 2015[update], the institute hosted more than 750 researchers who work to understand, prevent and treat diseases including blood, breast and ovarian cancers; inflammatory diseases (autoimmunity) such as rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes and coeliac disease; and infectious diseases such as malaria, HIV and hepatitis B and C.[3]

Located in Parkville, Melbourne, it is closely associated with The University of Melbourne and The Royal Melbourne Hospital. The institute also has a campus at La Trobe University. The Director of WEHI, since July 2009, is Professor Doug Hilton AO, FAA, a molecular biologist.

History

The institute was founded in 1915 using funds from a trust established by Eliza Hall following the death of her husband Walter Russell Hall. The institute owes its origin to the inspiration of Harry Brookes Allen, who encouraged the use of a small portion of the charitable trust to found a medical research institute.[4] The vision was for an institute that 'will be the birthplace of discoveries rendering signal service to mankind in the prevention and removal of disease and the mitigation of suffering.’

In April 1915 the new Melbourne Hospital agreed to provide a home for the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Research in Pathology and Medicine, as it was then known. A few weeks later, the new institute's director-designate, Gordon Mathison, suffered fatal wounds in the ANZAC Battle of Gallipoli. The floors set aside for the institute in the grounds of the old Melbourne Hospital were given over to the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories in 1918 until a new director could be secured at the cessation of hostilities.[5]

Sydney Patterson was appointed the first director and took up his post in 1919. Patterson resigned and returned to England in 1923. He was followed by Charles Kellaway for the critical years 1923-44. Kellaway formalised research streams, supported aspiring local researchers, built up public benefactions and secured the first Commonwealth grants for the institute's researches.[6] He also oversaw the plans and construction of the first separate institute building adjacent to the new Royal Melbourne Hospital, which opened in 1942. Under Kellaway's directorship, the institute came to achieve international recognition as a centre for excellence in medical research by the outbreak of World War II.[2]

Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet was the institute director between 1944 and 1965, and he brought the institute to international prominence for virological research, especially influenza, and then for immunology. Such was the nature of Burnet’s achievement that he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1960 with Sir Peter Medawar for the discovery of immunological tolerance.[2]

Sir Gustav Nossal succeeded Burnet as director in 1965, aged 35. Under his stewardship, the institute grew in size and scope, with its scientists making important discoveries in the control of immune system responses, cell cycle regulation and malaria.[7] During this time, the group led by Professor Donald Metcalf discovered and characterised the colony-stimulating factors (CSFs), which have benefited more than 10 million cancer patients worldwide.[8]

Between 1996 and 2009, it was led by Professor Suzanne Cory. Since July 2009, Professor Doug Hilton AO, FAA has been the director of WEHI.[9]

In the lead up to its centenary in 2015, the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute underwent significant building redevelopment. A new west wing was built in 2012, nearly doubling the institute's size, funded by the Victorian and Australian Governments and The Atlantic Philanthropies.[10]

In 2020, the institute rebranded itself to the simpler name WEHI, and updated its motto to Brighter together.[11]

Research

The institute focuses solely on medical research, centered around[citation needed]:

- Cancers (such as leukaemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, breast cancer and ovarian cancer)

- Inflammatory or autoimmune diseases (such as type 1 diabetes, coeliac disease, multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis)

- Infectious diseases (such as malaria, HIV and hepatitis B and C)

The institute is organised into the following 14 divisions (with current Division Heads in parentheses):[2][12]

- ACRF Chemical biology (A/Professor Isabelle Lucet)[13]

- ACRF Cancer and stem cells (Professors Geoff Lindeman and Jane Visvader)[14]

- Bioinformatics (Professors Gordon Smyth and Melissa Davis) [15]

- Blood Cells and Blood Cancer (Professor Andreas Strasser)[16]

- Clinical Translation (Professor Clare Scott and Professor Ian Wicks)[17]

- Epigenetics and Development (Professor Marnie Blewitt and Professor Anne Voss)[18]

- Immunology (Associate Professor Daniel Gray and Professor Phil Hodgkin)[19]

- Infectious Diseases and Immune Defence (A/Professor Wai-Hong Tham and Professor Marc Pellegrini)[20]

- Inflammation (Associate Professor James Murphy) [21]

- Personalised Oncology (Professor Peter Gibbs and Associate Professor Marie-Liesse Labat)[22]

- Population Health and Immunity (Professors Melanie Bahlo and Ivo Mueller)[23]

- Structural Biology (Associate Professor Matthew Call and Associate Professor Peter Czabotar)[24]

- Ubiquitin Signalling (Professor David Komander) [25]

The institute is one of five research centres to establish the ACRF Centre for Therapeutic Target Discovery - an Australian-first collaborative and comprehensive cancer research centre. The new consortium is funded by a $5 million grant awarded in 2006 by the Australian Cancer Research Foundation. The award is in honour of Australian businessman Sir Peter Abeles AC.[26]

Education

The institute forms the department of Medical Biology at the University of Melbourne; graduate students enrolled at the University who undertake research at the institute can obtain a Bachelor of Science (Honours), Bachelor of Biomedicine (Honours) or Doctor of Philosophy degree; medical students can also study for Advanced Medical Science. Undergraduate students can also be part of the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP). During the 2005–2006 financial year 17 students obtained a PhD at the WEHI, while 17 obtained a Bachelor of Science (Honours). As of June 2006, the Institute hosts 60 PhD students.[27]

The institute is also part of the Gene Technology Access Centre led by Chief Executive Officer Jacinta Duncan, located next to the institute building at University High School, which provides education programs in molecular and cell biology for secondary students in Victoria.[28]

Awards

- In 2019, David Vaux and Andreas Strasser were joint recipients of the Florey Medal for their work on revealing the links between cell death and cancer.[29][30]

- In 2020, David Vaux won the Bettison & James Award, presented by the Adelaide Film Festival.[31]

See also

References

- ^ "Annual Report 2015". Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research. 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d Fenner, Frank; Cory, Suzanne (1997). "The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute". Nobel Prize Foundation. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ "2014 Annual Report" (PDF). Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ Dale, H. H. (1 January 1953). "Charles Halliley Kellaway. 1889-1952". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 8 (22): 502–521. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1953.0013. S2CID 178195013.

- ^ Courtice, F. R. (1988). "Research in the medical sciences: The road to independence". In Home, Roderick (ed.). Australian Science in the Making. Cambridge University Press. pp. 277–307. ISBN 9780521396400.

- ^ Hobbins, PG; Winkel, KD (2007). "The forgotten successes and sacrifices of Charles Kellaway, director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, 1923-1944". The Medical Journal of Australia. 187 (11–12): 645–8. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01457.x. PMID 18072902. S2CID 23444263.

- ^ Charlesworth, Max (1989). Life among the scientists : an anthropological study of an Australian scientific community. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554999-6.

- ^ Nossal, Gustav (2007). Diversity and discovery: the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, 1965-1996. Miegunyah Press. ISBN 9780522851175.

- ^ "The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute announces the next Director" (Press release). Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. 24 February 2009.

- ^ "Parkville development". Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ "WEHI embarks on a new era of scientific discovery". WEHI. 16 October 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

We are better and brighter when we work together – that's something that is really at the heart of the WEHI ethos. The way the research community has responded to this pandemic is a wonderful example of the collaborative spirit we embody.

- ^ "Scientific divisions". WEHI. 8 May 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ "ACRF Chemical Biology". WEHI. 24 October 2014.

- ^ "ACRF Cancer Biology and Stem Cells". WEHI. 21 March 2019.

- ^ "Bioinformatics". WEHI. 13 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "Blood Cells and Blood Cancer". WEHI. 19 March 2019.

- ^ "Clinical Translation". WEHI. 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Epigenetics and Development". WEHI. 21 March 2019.

- ^ "Immunology". WEHI. 24 October 2014.

- ^ "Infectious Diseases and Immune Defence". WEHI. 17 April 2019.

- ^ "Inflammation". WEHI. 24 October 2014.

- ^ "Personalised Oncology". WEHI. 21 March 2019.

- ^ "Population Health and Immunity". WEHI. 10 August 2015.

- ^ "Structural Biology". WEHI. 24 October 2014.

- ^ "Ubiquitin Signalling". WEHI. 17 April 2019.

- ^ "ACRF Centre for Therapeutic Target Discovery". Australian Cancer Research Foundation.

- ^ "Annual Report 2005–2006". Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. 2006. pp. 126–129.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "About GTAC". www.gtac.edu.au. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ "Scientists revealing the links between cell death and cancer win $50,000 CSL Florey Medal for lifetime achievement". Australian Institute of Policy and Science. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ Ha, Tanya (22 June 2020). "When cells forget how to die – a hallmark of cancer". Scimex. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "The Bettison & James Award". Adelaide Film Festival. 9 September 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2020.