Day of Wrath

| Day of Wrath | |

|---|---|

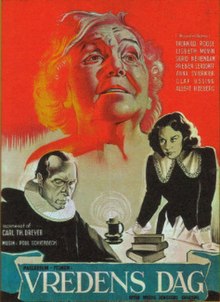

Danish theatrical release poster | |

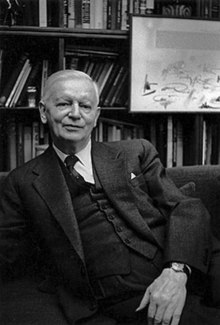

| Directed by | Carl Theodor Dreyer |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | Anne Pedersdotter by Hans Wiers-Jenssen |

| Produced by | Carl Theodor Dreyer |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Karl Andersson |

| Edited by | Anne Marie Petersen Edith Schlüssel |

| Music by | Poul Schierbeck |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 100 minutes[1] |

| Country | Denmark |

| Language | Danish |

Day of Wrath (Danish: Vredens dag) is a 1943 Danish drama film directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer and starring Lisbeth Movin, Thorkild Roose and Preben Lerdorff Rye. It is an adaptation of the 1909 play Anne Pedersdotter by Hans Wiers-Jenssen, based on a 16th century Norwegian case. The film tells the story of a young woman who is forced into a marriage with an elderly pastor after her late mother was accused of witchcraft. She falls in love with the pastor's son and also comes under suspicion of witchcraft.

The film was produced during the Nazi Occupation of Denmark, and Dreyer left the country for Sweden after its release. It has received very positive reviews, despite initial criticisms for slow pacing.

Plot

[edit]In a Danish village in 1623, an old woman known as Herlof's Marte is accused of witchcraft. Anne, a young woman, is married to the aged local pastor, Absalon Pedersson, who is involved with the trials of witches, and they live in a house shared with his strict, domineering mother Meret. Meret does not approve of Anne, who is much younger than her husband, being about the same age as the son from his first marriage. Anne gives Herlof's Marte refuge, but Marte is soon discovered in the house, though she is presumed to have hidden herself there without assistance. Herlof's Marte knows that Anne's mother, already dead at the time of the events depicted, had been accused of witchcraft as well, and had been spared thanks to Absalon's intervention, who aimed at marrying young Anne. Anne is thus informed by Herlof's Marte of her mother's power over people's life and death and becomes intrigued in the matter.

Absalon's son from his first marriage, Martin, returns home from abroad and he and Anne are immediately attracted to each other. She does not love her husband and thinks he does not love her. Under torture, Herlof's Marte confesses to witchcraft, defined among other evidence as wishing for the death of other people. She threatens to expose Anne if Absalon does not rescue her from a guilty verdict, begging him to save her as he saved Anne's mother. Marte, after pleading with Absalon a second time, does not betray his secret and is executed by burning with the villagers looking on. Absalon feels his guilt over having saved Anne's mother, but leaving Marte to burn. Anne and Martin, clandestinely growing closer, are seen as having changed in recent days, fueling Meret's suspicion of Anne's character. Anne is heard laughing in Martin's company by her husband, something which has not occurred in their time together. Absalon regrets that he married Anne without regarding her feelings and true intentions, and tells her so, apologizing for stealing her youth and happiness.

A violent storm erupts while Absalon is away visiting a dying young parishioner, Laurentius. He had been cursed by Herlof's Marte during her interrogation and she foretold an imminent death. Meanwhile, Anne and Martin are discussing the future, and she is forced to admit wishing her husband dead, but only as an "if" rather than it actually happening. At that moment Absalon, on his way home, feels "like the touching of Death itself." On Absalon's return, Anne confesses her love for Martin to her husband and tells him she wishes him dead. He collapses and dies, calling Martin's name. Anne screams. The following morning Martin is overcome by his own doubts. Anne declares that she had nothing to do with his father's death, which she sees as providential help from above to release her from her present misery and unhappy marriage. At Absalon's funeral, Anne is denounced by Meret, her mother-in-law, as a witch. Anne initially denies the charge, but when Martin sides with his grandmother she is faced with the loss of his love and trust, and she confesses on her husband's open coffin that she murdered him and enchanted his son with the Devil's help. Her fate appears sealed.[2]

Cast

[edit]- Thorkild Roose as Rev. Absalon Pederssøn

- Lisbeth Movin as Anne Pedersdotter, Absalon's second wife

- Preben Lerdorff Rye as Martin, Absalon's son from first marriage

- Sigrid Neiiendam as Merete, Absalon's mother

- Anna Svierkier as Herlofs Marte

- Albert Høeberg as the Bishop

- Olaf Ussing as Laurentius

- Preben Neergaard as Degn

- Kirsten Andreasen

- Sigurd Berg

- Harald Holst

- Emanuel Jørgensen

- Sophie Knudsen

- Emilie Nielsen

- Hans Christian Sørensen

- Dagmar Wildenbrück

Production

[edit]

Day of Wrath was Dreyer's first film since Vampyr (1932). He had spent the previous eleven years working as a journalist and unsuccessfully attempting to launch such film projects as an adaptation of Madame Bovary, a documentary on Africa and a film about Mary Stuart.[3]

Dreyer had first seen Wiers-Jenssen's play Anne Pedersdotter in 1925 and had wanted to adapt it to the screen for several years.[4] It differs slightly from the original play, such as the scene where Anne and Martin first meet and kiss. In Wiers-Jenssen's play they are hesitant and shy, while in Dreyer's film they are bluntly sexual.[5]

Dreyer's producers had wanted him to cast Eyvind Johan-Svendsen in the role of Absalon, but Dreyer thought the actor was too much of "a Renaissance man" and preferred to cast an actor that could project the austerity that he wanted.[6] Lisbeth Movin was cast after being asked to meet with Dreyer. She was not allowed to wear any make-up, with Dreyer preferring the realistic look.[7]

In one scene, Anna Svierkier's character is burnt at the stake. To depict it, Svierkier was tied to a wooden ladder, and Dreyer left her there while the rest of the cast and crew went for lunch, over the objections of Preben Lerdorff Rye and Thorkild Roose. When they returned, Svierkier was perspiring profusely, which is visible in the film.[8]

Although both this film and most of Dreyer's other films have been criticized as being too slow, Dreyer explained that neither his pacing nor his editing were slow, but that the movements of the characters on the screen were slow in order to build tension.[9]

Release

[edit]The film premiered at the World Cinema in Copenhagen on 13 November 1943.[10] Dreyer always denied the film as being analogous to persecution of Jews. However, on the advice of many of his friends he left Denmark on the pretext of selling Day of Wrath in foreign markets and spent the rest of the war in Sweden shortly after the film's release.[11][12]

The film premiered in the United States in April 1948.[13] In Region 1, The Criterion Collection released the film on DVD in 2001, in a boxset with Dreyer's Ordet (1955) and Gertrud (1964).[14]

Reception

[edit]On its Copenhagen release, it received poor reviews and was unsuccessful financially, with many Danes complaining about the film's slow pace.[15] It later gained a better critical reputation after World War II. Many Danes saw a parallel between the witch burning and the persecution of Jews during the Nazi occupation, which had begun on 29 August.[10] While Dreyer denied the film was about the Nazis, during the war it had resonated with the Danish resistance movement.[16]

The film also received negative criticism in the United States in 1948. Variety wrote that "the picture is tedious to the extreme," and that its "chief trouble lies in the gratingly plodding pace. And the heavy story, unlightened by the slightest sign of comedy relief."[17] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called the film "slow and monotonous" despite having "intellectual force."[13]

However, from some reviewers, the film received immediate praise. The New Yorker called the film "one of the best ever made."[18] A. Bertrand Channon called the film a "masterpiece" that will be "discussed long after Greer Garson, Bette Davis, and Ida Lupino have joined the company of Ruth Chatterton, Norma Talmadge, and Norma Shearer."[19] Life magazine called it "one of the most remarkable movies of recent years" and noted that a campaign by a group of critics led to the film being shown again four months later in August 1948.[20]

Years after its release, film critic Robin Wood called it "Dreyer's richest work...because it expresses most fully the ambiguities inherent in his vision of the world."[21] Jean Semolue said that "the interest in Dreyer's films resides not in the depiction of events, nor the predetermined characters, but in the depiction of the changes wrought on characters by events.[11]

Critic Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote that "Day of Wrath may be the greatest film ever made about living under totalitarian rule"[22] and believed it was an influence on the play The Crucible by Arthur Miller.[16] It is often cited in Denmark as the greatest Danish film.[23] Currently, the film has a 100% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 25 reviews, with a weighted average of 8.68/10. The site's consensus reads: "Beautifully filmed and rich with period detail, Day of Wrath peers into the past to pose timelessly thought-provoking questions about intolerance and societal mores".[24]

References

[edit]- ^ "Day of Wrath". British Board of Film Classification. 11 December 1946. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ^ Dreyer 1970, pp. 133–235.

- ^ Milne 1971, p. 121.

- ^ Dreyer 1970, p. 17.

- ^ Dreyer 1970, p. 18.

- ^ Milne 1971, p. 147.

- ^ Torben Skjodt Jensen (Director), Lisbeth Movin (1995). Carl Th. Dreyer: My Metier (Motion picture). Steen Herdel & Co. A/S.

- ^ Torben Skjodt Jensen (Director) (1995). Carl Th. Dreyer: My Metier (Motion picture). Steen Herdel & Co. A/S.

- ^ Milne 1971, p. 127.

- ^ a b Milne 1971, p. 125.

- ^ a b Wakeman 1987, p. 271.

- ^ Milne 1971, p. 20.

- ^ a b Crowther, Bosley (26 April 1948). "' Day of Wrath' Is New Feature at Little Carnegie -- French Film Opens at Rialto". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ "Carl Theodor Dreyer Box Set". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Milne 1971, p. 126.

- ^ a b Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "Figuring Out Day of Wrath". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ "Day of Wrath". Variety. April 1948.

- ^ "Melancholy Dane". The New Yorker. Vol. 24. 1948. p. 82.

- ^ Channon, A. Bertrand (August 1948). "Messages in Millimeters". Saturday Review of Literature. 31: 35.

- ^ "Day of Wrath: A Somber Tale of Death and Witchcraft Laid in 17th-Century Denmark Makes A Modern Movie Classic". Life. Vol. 25. September 1948. p. 61.

- ^ Wakeman 1987, p. 270.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (22 August 2003). "Day of Wrath". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ Jensen 2002.

- ^ "Day of Wrath (2008)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Dreyer, Carl Theodor (1970). Four Screenplays. Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-12740-8.

- Jensen, Bo Green (2002). De 25 bedste danske film. Rosinante. ISBN 87-621-0081-5.

- Milne, Tom (1971). The Cinema of Carl Dreyer. New York: A. S. Barnes & Co.

- Wakeman, John (1987). World Film Directors. Vol. 1. The H. W. Wilson Company.

External links

[edit]- Day of Wrath at IMDb

- Day of Wrath at the British Board of Film Classification

- Day of Wrath at Rotten Tomatoes

- Figuring Out Day of Wrath an essay by Jonathan Rosenbaum at the Criterion Collection

- 1943 films

- 1940s historical drama films

- Films about adultery

- Danish black-and-white films

- Danish Culture Canon

- Danish films based on plays

- Danish historical drama films

- 1940s Danish-language films

- Films about capital punishment

- Films about witchcraft

- Films directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer

- Films scored by Poul Schierbeck

- Films set in Denmark

- Films set in 1623

- Films about witch hunting

- 1943 drama films