User:Paul August/Stheno and Euryale

To Do

[edit]Current text

[edit]New text

[edit]Mythology

[edit]The cry which emanated from the Gorgons seems to have been notable, however Euryale's lamenting cry, while chasing Perseus, was apparently particularly so. Although Pindar mentions the "dire dirge of the reckless Gorgons" while chasing Perseus, he has Athena create the "many-voiced songs of flutes" to imitate the "shrill cry" of the "fast-moving jaws of Euryale".[1] While Nonnus, in his Dionysiaca, has the fleeing Perseus "listening for no trumpet but Euryale's bellowing".[2]

- ^ Gantz, p. 20; Pindar, Pythian 12.20.

- ^ Nonnus, Dionysiaca 25.58; see also Dionysiaca 13.77–78, 30.265–266.

Iconography

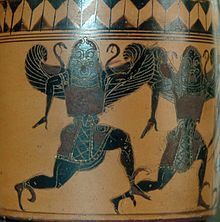

[edit]The typical archaic (c. 8th–5th century BC) depictions of Stheno and Euryale, show their head turned to face the viewer, sitting (seemingly without a neck) atop a running body in profile, with wings on its back and curl-topped boots. In later depictions the heads shrink in size with respect to their bodies, possess necks, and become less wild looking.[1]

- ^ Wilke, pp. 31–35. For images of a running Gorgon, see Hard, p. 59 fig. 2.5 and Wilke p. 33 fig. 3.4 (left).

References

[edit]Sources

[edit]Ancient

[edit]- 798–800

- And near them [the Graeae] are their three winged sisters, the snake-haired Gorgons, loathed of mankind, [800] whom no one of mortal kind shall look upon and still draw breath.

- And to Sea ( Pontus) and Earth were born Phorcus, Thaumas, Nereus, Eurybia, and Ceto. Now to Thaumas and Electra were born Iris and the Harpies, Aello and Ocypete; and to Phorcus and Ceto were born the Phorcides and Gorgons, of whom we shall speak when we treat of Perseus.

- ...Now Perseus having declared that he would not stick even at the Gorgon's head, Polydectes ... ordered him to bring the Gorgon's head. So under the guidance of Hermes and Athena he made his way to the daughters of Phorcus, to wit, Enyo, Pephredo, and Dino; for Phorcus had them by Ceto, and they were sisters of the Gorgons, and old women from their birth. ... And [Perseus] flew to the ocean and caught the Gorgons asleep. They were Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa. Now Medusa alone was mortal; for that reason Perseus was sent to fetch her head. But the Gorgons had heads twined about with the scales of dragons, and great tusks like swine's, and brazen hands, and golden wings, by which they flew; and they turned to stone such as beheld them.

- So Perseus put the head of Medusa in the wallet (kibisis) and went back again; but the Gorgons started up from their slumber and pursued Perseus: but they could not see him on account of the cap, for he was hidden by it.

- 986–991

- Creusa

- Listen, then; you know the battle of the giants?

- Creusa

- Tutor

- Yes, the battle the giants fought against the gods in Phlegra.

- Tutor

- Creusa

- There the earth brought forth the Gorgon, a dreadful monster.

- Creusa

- Tutor

- [990] As an ally for her children and trouble for the gods?

- Tutor

- Creusa

- Yes; and Pallas, the daughter of Zeus, killed it.

- Creusa

- 270–277

- And again, Ceto bore to Phorcys the fair-cheeked Graiae, sisters grey from their birth: and both deathless gods and men who walk on earth call them Graiae, Pemphredo well-clad, and saffron-robed Enyo, and the Gorgons who dwell beyond glorious Ocean [275] in the frontier land towards Night where are the clear-voiced Hesperides, Sthenno, and Euryale, and Medusa who suffered a woeful fate: she was mortal, but the two were undying and grew not old.

- 229–237

- Perseus himself, Danae’s son, was outstretched, and he looked as though he were hastening and shuddering. The Gorgons, dreadful and unspeakable, were rushing after him, eager to catch him; as they ran on the pallid adamant, the shield resounded sharply and piercingly with a loud noise. At their girdles, two serpents hung down, their heads arching forward; both of them were licking with their tongues, and they ground their teeth with strength, glaring savagely. Upon the terrible heads of the Gorgons rioted great Fear.

- 13.77–78

- Mycalessos with broad dancing-lawns, named to remind us of Euryale’s throatc

- c Euryale, a Gorgon; Nonnos derives the town’s name from the monster’s roar, μυκηθμός, μυκάομαι.

- Mycalessos with broad dancing-lawns, named to remind us of Euryale’s throatc

- 25.53–58

- Perseus fled with flickering wings trembling at the hiss of mad Sthenno’s hairy snakes, although he bore the cap of Hades and the sickle of Pallas, with Hermes’ wings though Zeus was his father; he sailed a fugitive on swiftest shoes, listening for no trumpet but Euryale’s bellowing

- 30.265–266

- Have you seen the eye of Sthenno which turns all to stone, or the bellowing invincible throat of Euryale herself?

- 40.227–233

- The double Berecyntian pipes in the mouth of Cleochos drooned a gruesome Libyan lament, one which long ago both Sthenno and Euryale with one many throated voice sounded hissing and weeping over Medusa newly gashed, while their snakes gave out voice from two hundred heads, and from the lamentations of their curling and hissing hairs they uttered the “manyheaded dirge of Medusa.”a

- a Pindar, Pyth. xii. 23 gives this origin of the tune called πολυκέφαλος—πολλᾶν κεφαλᾶν νόμον, the tune of many heads.

- The double Berecyntian pipes in the mouth of Cleochos drooned a gruesome Libyan lament, one which long ago both Sthenno and Euryale with one many throated voice sounded hissing and weeping over Medusa newly gashed, while their snakes gave out voice from two hundred heads, and from the lamentations of their curling and hissing hairs they uttered the “manyheaded dirge of Medusa.”a

Phythian

- 10.46–48

- ...[Perseus] killed the Gorgon, and came back bringing stony death to the islanders, the head that shimmered with hair made of serpents.

- 12.6–20

- ... that art [flute playing] which once Pallas Athena discovered when she wove into music the dire dirge of the reckless Gorgons which Perseus heard [10] pouring in slow anguish from beneath the horrible snakey hair of the maidens, when he did away with the third sister and brought death to sea-girt Seriphus and its people. Yes, he brought darkness on the monstrous race of Phorcus, and he repaid Polydectes with a deadly wedding-present for the long [15] slavery of his mother and her forced bridal bed; he stripped off the head of beautiful Medusa, Perseus, the son of Danae, who they say was conceived in a spontaneous shower of gold. But when the virgin goddess had released that beloved man from those labors, she created the many-voiced song of flutes [20] so that she could imitate with musical instruments the shrill cry that reached her ears from the fast-moving jaws of Euryale.

Modern

[edit]Bremmer, Jan N.

[edit]- s.v. Gorgo/Medusa

- Female monsters in Greek mythology. According to the canonical version of the myth (Apollod. 2. 4. 1–2) Perseus (1) was ordered to fetch the head of Medusa, the mortal sister of Sthenno and Euryale; through their horrific appearance these Gorgons turned to stone anyone who looked at them. ... Although pursued by Medusa's sisters, Perseus escaped ...

Gantz

[edit]p. 20

- In contrast ... The Aspis offers a typically garish portrait: Gorgons with twin snakes ... wrapped around their wastes ... and possibly a vague reference to snakes for hair (Aspis 229-37). Snaky locks are in any case well attested by Pindar (Py 10.46-48; 12.9-12), ... Euryale's lament becomes the model for the song of the flute.

Tripp

[edit]s.v. Gorgons

- Three Snaky-haired monsters, named Steno, Euryale, and Medusa. Euripides says that Ge brought forth "the Gorgon" to aid her children, the Giants, in their war with the gods. Others claim that the Gorgons were among the brood that sprang from the union of the ancient sea-god Phorcys and his sea-monster sister, Ceto; these offspring included Echidna, Ladin, and the Graeae. The Gorgons had brazen hands and wings of gold; red tongues lolled from their mouths between tusks like those of swine; and serpents writhed about their heads. Their faces were so hideous that a glimpse of them would turn man or beast to stone. Of the three, only Medusa was mortal. She was killed by Perseus. [Hesiod, Theogony, 270-283. See also references un der PERSEUS.]

Wilke

[edit]Iconographic

[edit]Paris, Cabinet des Medailles 277

[edit]

Mack, p. 581

- 6. The pursuit of Perseus, Attic black-figure lekythos, c. 540. Courtesy of the Cabinet des médailles, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris (277).

- On a mid-sixth-century lekythos we see the panicked confusion of Medusa, who is turned around and collapsing while Perseus runs free; we are to imagine the monster's head tossed into the pouch that dangles from the hero's left arm (plate 6.).

Beazley Archive 1102

- Fabric: ATHENIAN

- Technique: BLACK-FIGURE

- Shape Name: LEKYTHOS

- Date: -550 to -500

- Decoration: Body: (PERSEUS AND THE GORGONS) GORGONS CHASING PERSEUS, MEDUSA FALLING, ATHENA, ::HERMES IN NEBRIS

- Shoulder: HORSEMEN, YOUTH, DRAPED FIGURES

- Current Collection: Paris, Cabinet des Medailles: 277

Paris, Louvre E874, the Dinos of the Gorgon Painter

[edit]

- Gantz, p. 21

- By the time of the name vases of Nessos and Gorgon Painters of Athens (end of the seventh century: Athens 1002, Louvre E874), canonical features, such as the tripartite nose and lolling tongue (perhaps developed in Corinthian painting), are basically in force;

- Krauskopf and Dahlinger, p. 313, no. 314

- Dinos ... Louvre E 874 ... Um 590 v.Chr. ... Knielaufschema weniger ausgeprägt, Flügelschuhe, Schlangen über dem Kopf.im Knielaufschema, kurzes Gewand, zwei Flügel, Volutennase, gebogenes Maul mit Hauern und Zunge, Bart.

- ... [Knee-walking scheme less pronounced, winged shoes, snakes over the head. in the knee-walking scheme, short robe, two wings, volute nose, curved mouth with tusks and tongue, beard.]

- Perseus Louvre E 874 (Vase)

- Date: ca. 590 BC

- On side B, Perseus has beheaded Medusa. As she falls, her two sisters run to the right after Perseus. Hero and gorgons all wear similar winged shoes and short chitons.

- Beazley Archive 300055

- Date: -600 to -550

- LIMC IV-2, p. 185 (Gorgo, Gorgones 314)

- ^ Gantz, p. 21; Krauskopf and Dahlinger, p. 313, no. 314; Perseus Louvre E 874 (Vase); Beazley Archive 300055; Digital LIMC 4022; LIMC IV-2, p. 185 (Gorgo, Gorgones 314).

- ^ Gantz, p. 21; Krauskopf and Dahlinger, p. 313, no. 314; Perseus Louvre E 874 (Vase); Beazley Archive 300055; Digital LIMC 4022; LIMC IV-2, p. 185 (Gorgo, Gorgones 314).