Turks in Germany

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,000,000 - 7,000,000

1.3 million with Turkish citizenship (Statistical Office of the European Union 2023)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Turkish, Kurdish, Circassian, German, English | |

| Religion | |

| Mostly Sunni Muslim, partly Alevi, agnostic, atheist, Christian[3][4] or other religions |

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: MOS:SANDWICH. (November 2024) |

Turks in Germany, also referred to as German Turks and Turkish Germans (German: Türken in Deutschland/Deutschtürken; Turkish: Almanya'daki Türkler), are ethnic Turkish people living in Germany. These terms are also used to refer to German-born individuals who are of full or partial Turkish ancestry.

However, not all people in Germany who trace their heritage back to Turkey are ethnic Turks. A significant proportion of the population is also of Kurdish, Circassian, Azerbaijani descent and to a lesser extent, of Christian descent, such as Assyrian, and Armenian. Also some ethnic Turkish communities in Germany trace their ancestry to other parts of southeastern Europe or the Levant (such as Balkan Turks and Turkish Cypriots). At present, ethnic Turkish people form the largest ethnic minority in Germany.[5] They also form the largest Turkish population in the Turkish diaspora.[citation needed]

Most people of Turkish descent in Germany trace their ancestry to the Gastarbeiter (guest worker) programs in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1961, in the midst of an economic boom that resulted in a significant labor shortage, Germany signed a bilateral agreement with Turkey to allow German companies to recruit Turkish workers. The agreement was in place for 12 years, during which around 650,000 workers came from Turkey to Germany. Many also brought their spouses and children with them.

Turks who immigrated to Germany brought cultural elements with them, including the Turkish language.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Turkish migration from the Seljuk Empire and the Rum Seljuk Sultanate

[edit]During a series of invading Crusades by European-Christian armies into lands ruled by Turkic rulers in the Middle East, namely under the Seljuk Turks in the Seljuk Empire and the Rum Seljuk Sultanate (but also the Bahri Mamluk Sultanate), many crusaders brought back Turkish male and female prisoners of war to Europe; women were generally baptised and then married whilst "every returning baron and count had [male] prisoners of war in his entourage."[6] Some of the Beutetürken ('booty Turks') taken to Germany during the Crusades also included children and young adults.[7]

The earliest documented Turk in Germany is believed to be Sadok Seli Soltan (Mehmet Sadık Selim Sultan) (ca.1270-1328) from the Anatolian Seljuk lands.[8][9] According to Streiders Hessisches Gelehrtenlexikon, Soltan was a Turkish officer who was captured by Count von Lechtomir (Reinhart von Württemberg) during his return to Germany from the Holy Land in 1291. By 1304 Soltan married Rebekka Dohlerin; he was baptised the following year as "Johann Soldan", but "out of special love to him", the Count "gave him a Turkish nobility coat of arms".[6] Soldan and his wife had at least three sons, including Eberhardus, Christanianus and Melchior.[6] Another source specifies that Soltan came with Count Reinhart von Württemberg to the residential town of Brackenheim in 1304 and was then baptised in 1305 at S. Johannis Church as "Johannes Soldan".[6] There is also evidence that Soltan had a total of 12 sons born in 20 years with Anna Delcherin and Rebecca Bergmännin; eight of his sons passed to the clergy and do not appear in genealogy records due to compulsory celibacy associated with the clergy.[10]

Soltan/Soldan's descendants, who were more widespread in south-west Germany, include notable German artists, scholars, doctors, lawyers and politicians.[11] For example, through his maternal grandmother, the renowned German poet and writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe belonged to the descendants of the Soldan family and thus had Turkish ancestry.[12][13][14][15][16][6] Bernt Engelmann has said that "the German poet prince [i.e. Goethe] with oriental ancestors is by no means a rare exception."[6] Indeed, other descendants of the first recorded Turk in Germany include the lawyer Hans Soldan;[17] the city architects and wine masters Heinrich Soldan and his son Johann Soldan who both served as Mayor of Frankenberg;[10][18] the sculptor and artist Philipp Soldan;[19] and the pharmacist Carl Soldan who founded the confectionery company "Dr. C. Soldan".[20] Carl Soldan's grandson, Pery Soldan, has said that the family continue to use the crescent and star on their coat of arms.[21][7] According to Latif Çelik, as of 2008, the Soldan family numbered 2,500 and are also found in Austria, Finland, France and Switzerland.[22]

Turkish migration from the Ottoman Empire

[edit]

The Turkish people had greater contact with the German states by the sixteenth century when the Ottoman Empire attempted to expand their territories beyond the north Balkan territories. The Ottoman Turks held two sieges in Vienna: the first Siege of Vienna in 1529 and the Second Siege of Vienna in 1683. The aftermath of the second siege provided the circumstances for a Turkish community to permanently settle in Germany.[29][30]

Many Ottoman soldiers and camp followers who were left behind after the second siege of Vienna became stragglers or prisoners. It is estimated that at least 500 Turkish prisoners were forcibly settled in Germany.[23] Historical records show that some Turks became traders or took up other professions, particularly in southern Germany. Some Turks fared very well in Germany; for example, one Ottoman Turk is recorded to have been raised to the Hanoverian nobility.[30] Historical records also show that many Ottoman Turks converted to Christianity and became priests or pastors.[30]

The aftermath of the second siege of Vienna led to a series of wars between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League, known as the "Great Turkish War", or the "War of the Holy League", which led to a series of Ottoman defeats. Consequently, more Turks were taken by the Europeans as prisoners. The Turkish captives taken to Germany were not solely made up of men. For example, General Schöning took "two of the most beautiful women in the world" in Buda who later converted to Christianity.[26] Another Turkish captive named Fatima became the mistress of Augustus II the Strong, Elector of Saxony of the Albertine line of the House of Wettin. Fatima and Augustus had two children: their son, Frederick Augustus Rutowsky, became the commander of the Saxon army in 1754-63[26] whilst their daughter, Maria Anna Katharina Rutowska, married into Polish nobility. Records show that at this point it was not uncommon for Turks in Germany to convert to Christianity. For example, records show that 28 Turks converted to Christianity and were settled in Württemberg.[26]

With the establishment of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701, Turkish people continued to enter the German lands as soldiers employed by the Prussian kings.[29] Historical records show that this was particularly evident with the expansion of Prussia in the mid-18th century. For example, in 1731, the Duke of Kurland presented twenty Turkish guardsmen to King Frederick William I, and at one time, about 1,000 Muslim soldiers are said to have served in the Prussian cavalry.[30] The Prussian king's fascination with the Enlightenment was reflected in their consideration for the religious concerns of their Muslim troops. By 1740 Frederick the Great stated that:

"All religions are just as good as each other, as long as the people who practice them are honest, and even if Turks and heathens came and wanted to populate this country, then we would build mosques and temples for them."[33]

By 1763, an Ottoman legation existed at the Prussian court in Berlin. Its third envoy, Ali Aziz Efendi, died in 1798 which led to the establishment of the first Muslim cemetery in Germany.[34] However, several decades later, there was a need for another cemetery, as well as a mosque, and the Ottoman sultan Abdulaziz was given permission to patronize a mosque in Berlin in 1866.[29][30]

Once trading treaties were established between the Ottomans and the Prussians in the nineteenth century, Turks and Germans were encouraged to cross over to each other's lands for trade.[35] Consequently, the Turkish community in Germany, and particularly in Berlin, grew significantly (as did a German community in Istanbul) in the years before the First World War.[30] These contacts influenced the building of various Turkish-style structures in Germany, such as the Yenidze cigarette factory in Dresden[32] and the Dampfmaschinenhaus für Sanssouci pumping-station in Potsdam.

During this time, there were also marriages between Germans and Turks. For example, Karl Boy-Ed, who was the naval attaché to the German embassy in Washington during World War I, was born into a German-Turkish family.[27][28]

Turkish migration from the Republic of Turkey

[edit]

Heuss-Turks

[edit]The Heuss Turks were the name given to around 150 young Turkish citizens who came to Germany in 1958. They followed an invitation that the then Federal President Theodor Heuss had extended to Turkish vocational school graduates during a visit to Turkey in Ankara in 1957. The exchange, which was intended as a vocational training measure and began for some of the group as apprentices at the Ford plant in Cologne, became the starting point for their immigration to the Federal Republic for some. A number worked at Ford until they retired in the late 1980s/early 1990s. It was the first large group of Turkish workers to come to Germany together, even before the start of actual Turkish immigration with the recruitment agreement between the Federal Republic of Germany and Turkey in 1961. According to DOMiD reports, they were given a warm welcome in Germany and were extremely popular with their work colleagues.[36]

Turkish Student Federation in Germany

[edit]The Turkish Student Federation in Germany (ATÖF; Turkish: Almanya Türk Öğrenci Federasyonu) is a nationwide interest group for Turkish students in Germany founded in 1962, which was dissolved in 1977. The first regional German-Turkish student association after the Second World War was founded in Munich in 1954. In the following years, others were founded, including in Berlin and Karlsruhe in 1957. The ATÖF was founded in 1962 as a merger of nine such student associations. Its founding location was again Munich. In 1977, the ATÖF was dissolved due to internal problems.[37]

In the 1950s, West Germany experienced an economic boom (Wirtschaftswunder, or 'economic miracle'), exacerbated by the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961 that prevented migration from East Germany. In response, the West German government signed a labour recruitment agreement with Turkey on 30 October 1961 and officially invited Turkish workers to emigrate to the country, initially on visas limited to two years, although this was quickly lifted following complaints by German employers.[38]

Most Turkish immigrants intended to live there temporarily and then return to Turkey so that they could build a new life with the money they had earned. Indeed, return-migration increased during the recession of 1966–1967 and the 1973 oil crisis. Under Helmut Kohl, the government also attempted to encourage immigrants to return to their countries of origin with financial incentives, although this was largely unsuccessful.[39] Overall, the proportion of Turkish immigrants who returned to Turkey remained relatively small.[40] This was partly due to the family reunification rights that were introduced in 1974 which allowed Turkish workers to bring their families to Germany.[41] Consequently, between 1974 and 1988 the number of Turks in Germany nearly doubled, acquiring a balanced sex ratio and a much younger age profile than the German population.[42] Once the recruitment of foreigner workers was reintroduced after the recession of 1967, the BfA (Bundesversicherungsanstalt für Angestellte) granted most work visas to women. This was in part because labour shortages continued in low paying, low-status service jobs such as electronics, textiles, and garment work; and in part to further the goal of family reunification.[43]

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the reunification of East and West Germany, was followed by intense public debate around national identity and citizenship, including the place of Germany's Turkish minority in the future of a united Germany. These debates about citizenship were accompanied by expressions of xenophobia and ethnic violence that targeted the Turkish population.[44] Anti-immigrant sentiment was especially strong in the four former eastern states of Germany, which underwent profound social and economic transformations during the reunification process. Turkish communities experienced considerable fear for their safety throughout Germany, with some 1,500 reported cases of right wing violence, and 2,200 cases the year after.[45] The political rhetoric calling for foreigner-free zones (Ausländer-freie Zonen) and the rise of neo-Nazi groups sharpened public awareness of integration issues and generated intensified support among liberal Germans for the competing idea of Germany as a "multicultural" society. Citizenship by birth was restricted to the children of German citizens until the mid-2000s. However, increasing numbers of second-generation Turkish-Germans have opted for German citizenship and are becoming more involved in the political process.[46]

Turkish migration from the Balkans

[edit]Bulgaria

[edit]

Initially, Turkish Bulgarians arrived in Germany following the introduction of family reunification laws in 1974. They were able to take advantage of this law despite the very small number of Bulgarian citizens in Germany because some Turkish workers in Germany who arrived from Turkey were actually part of the Turkish minority who had left Bulgaria during the communist regime in the 1980s and still held Bulgarian citizenship, alongside their Turkish citizenship.[49]

The migration of Turkish Bulgarians to Germany increased further once communism in Bulgaria ended in 1989. In particular, Turkish Bulgarians who did not join the massive migration wave to Turkey during the so-called "Revival Process" faced severe economic disadvantages and discrimination resulting from the state policies of Bulgarisation. Hence, from the early 1990s onwards many Bulgarian Turks sought asylum in Germany.[50][51]

The number of Turkish-speaking Roma people from Bulgaria in Germany has significantly increased since Bulgaria was admitted into the European Union, which has allowed many Bulgarian Turkish Roma to use the freedom of movement to enter Germany.[52] The Bulgarian Turkish Roma have generally been attracted to Germany because they rely on the well-established Turkish-German community for gaining employment.[53]

Thus, the social network of the first waves of political emigration, as well as the preservation of kinship, has opened an opportunity for many Turkish Bulgarian to continue to migrate to Western Europe,[54] with the majority continuing to settling in Germany. As a result, Turkish Roma from Bulgaria in Germany outnumber the large Turkish Roma Bulgarian diasporas in countries such as the Netherlands,[53] where they make up about 80% of Bulgarian citizens.[55]

Greece

[edit]

From the 1950s onward, the Turkish minority of Greece, particularly the Turks of Western Thrace, began to immigrate to Germany alongside other Greek citizens.[57] Whilst many Western Thrace Turks had intended to return to Greece after working for a number of years, a new Greek law was introduced which effectively forced the minority to remain in Germany. Article 19 of the Greek Nationality Law gave the government the power to strip "non-ethnic" Greek citizens of their citizenship upon leaving the country without the possibility of an appeal. This law continued to affect Western Thrace Turks studying in Germany in the late 1980s, even those who had intended to return to Greece. It was not repealed until 1998.[58]

Despite risking the loss of their Greek citizenship, Western Thrace Turks continued to emigrate to Germany in large numbers. Firstly, in the 1960s and 1970s many came to Germany because the Thracian tobacco industry was affected by a severe crisis and many tobacco growers lost their income. Between 1970 and 2010, approximately 40,000 Western Thrace Turks emigrated to Western Europe, most of whom settled in Germany.[59] In addition, between 2010 and 2018, a further 30,000 Western Thrace Turks left for Western Europe due to the Greek government-debt crisis.[59] Of these 70,000 immigrants (which excludes the numbers which arrived before 1970),[59] around 80% live in Germany.[60]

In 2013 Cemile Giousouf became the first Western Thrace Turk to become a member of the German parliament. She was the first Muslim to be elected for the Christian Democratic Union of Germany.

North Macedonia

[edit]There has been migration from the Turkish Macedonian minority group which have come to Germany alongside other citizens of North Macedonia, including ethnic Macedonians and Albanian Macedonians.[61]

In 2021, Furkan Çako, who is a former Macedonian minister and member of the Security Council, urged Turkish Macedonians living in Germany to participate in North Macedonia's 2021 census.[62]

Romania

[edit]Between 2002 and 2011 there was a significant decrease in the population of the Turkish Romanian minority group due to the admission of Romania into the European Union and the subsequent relaxation of the travelling and migration regulations. Hence, Turkish Romanians, especially from the Dobruja region, have joined other Romanian citizens (e.g. ethnic Romanians, Tatars, etc.) in migrating mostly to Germany, Austria, Italy, Spain and the UK.[63]

Turkish migration from the Levant

[edit]Cyprus

[edit]

Turkish Cypriots migrants began to leave the island of Cyprus for Western Europe due to economic and political reasons in the 20th century, especially after the Cyprus crisis of 1963–64 and then the 1974 Cypriot coup d'état carried out by the Greek military junta which was followed by the reactionary Turkish invasion of the island. More recently, with the 2004 enlargement of the European Union, Turkish Cypriots who hold Cypriot citizenship have had the right to live and work across the European Union, including in Germany, as EU citizens. As of 2016, there are approximately 2,000 Turkish Cypriots in Germany,[65] which is the second largest Turkish Cypriot diaspora in Western Europe (after the UK).[65]

The TRNC (unrecognised) provides assistance to its Turkish Cypriots residents living in Germany via the TRNC Berlin Honorary Representative Office; the TRNC Köln Honorary Representative Office; the TRNC Bavarian Honorary Attaché; and the TRNC Bavarian Honorary Representative Office. These Representative Offices and Honorary Representatives also promote friendly relations between Northern Cyprus and Germany, as well as economic and cultural relations.[66][67]

Lebanon

[edit]Due to the numerous wars in Lebanon since the 1970s onwards, many Turkish Lebanese people have sought refuge in Turkey and Europe, particularly in Germany. Indeed, many Lebanese Turks were aware of the large Turkish-German population and saw this as an opportunity to find work once settling in Europe. In particular, the largest wave of Turkish Lebanese migration occurred once the Israel-Lebanon war of 2006 began. During this period more than 20,000 Turks fled Lebanon, particularly from Beirut, and settled in European countries, including Germany.[68]

Iraq

[edit]In 2008 there were 85,000 Iraqis living in Germany, of which approximately 7,000 were from the Turkish Iraqi minority group; hence, the Iraqi Turks formed around 8.5% of the total number of Iraqi citizens living in Germany.[70] The majority of Iraqi Turks live in Munich.

Syria

[edit]Established in Germany, the Suriye Türkmen Kültür ve Yardımlaşma Derneği – Avrupa, or STKYDA, ('Syrian Turkmen Culture and Solidarity Association – Europe') was the first Syrian Turkmen association to be launched in Europe.[71] It was established in order to help the growing Syrian Turkmen community which arrived in the country since the European migrant crisis which started in 2014 and saw its peak in 2015. The association includes Syrian Turkmen youth activists originating from all Syrian cities and who are now living across Western European cities.[72]

Turkish migration from the modern diaspora

[edit]In addition to ethnic Turkish people that have migrated to Germany from post-Ottoman modern nation-states, there has also been an increasing migration wave from the modern Turkish diaspora. For example, members of the Turkish Dutch community have also arrived in Germany as Dutch citizens. According to a study by Petra Wieke de Jong, focusing on second-generation Turkish-Dutch people specifically born between the years 1983 and 1992 only, 805 people from this age group and generation reported Germany as their country of emigration in 2001 to 2017. A further 1,761 people in this group did not report their emigration destination.[73]

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]

German state data and estimates

[edit]The German state does not allow citizens to self-declare their identity; consequently, the statistics published in the official German census does not show data on ethnicity.[75] According to the 2023 estimation, roughly 3 million German residents had a "migration background" from Turkey.[2]

Academic estimates

[edit]Throughout the decades estimates by academics of the Turkish-German population have varied. In 1990, David Scott Bell et al. put it at between 2.5 million and 3 million Turks in Germany.[76] A lower 1993 estimate by Stephen J. Blank et al. said there were 1.8 million Turks.[77] The German Government's Special Commission on Integration Barbara John estimated[when?] that there were more than 3 million Turks, including third-generation descendants, and that 79,000 new babies were born each year within the community.[78] The estimate of three million was also given by other scholars in the mid-1990s.[79][80] A higher estimate of 4 million Turks (including three generations) was reported by John Pilger in 1993[81] and the Deutsches Orient-Institut in 1994.[82] Moreover, Marilya Veteto-Conrad said that in the German capital there was already "over a million Turks in Berlin alone" in 1996.[83]

In 2003, Ina Kötter et al. said that there was "more than 4 million people of Turkish origin" in Germany;[84] this has also been reiterated by other scholars.[85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92] However, Michael Murphy Andregg said that by the 2000s "Germany was home to at least five million Turks";[93] various scholars have also given this estimate.[94][95][96][97][98] Jytte Klausen cited German statistics in 2005 showing 2.4 million Turks, but acknowledged that unlike Catholics, Protestants, and Jews, the Turkish community cannot allocate their ethnic or religious identity in official counts.

Settlements

[edit]

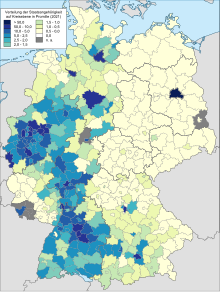

The Turkish community in Germany is concentrated predominantly in urban centers. The vast majority are found in the former West Germany, particularly in industrial regions such as the states of North Rhine-Westphalia (where a third of Turkish Germans live),[99] and Baden-Württemberg and the working-class neighbourhoods of cities like Berlin, Hamburg, Bremen, Bochum, Bonn, Cologne, Dortmund, Duisburg, Düsseldorf, Essen, Frankfurt, Hanover, Heidelberg, Mannheim, Mainz, Nuremberg, Munich, Stuttgart, Aachen and Wiesbaden.[100][101] Among the German districts in 2011, Duisburg, Gelsenkirchen, Heilbronn, Herne and Ludwigshafen had the highest shares of migrants from Turkey according to census data.[102]

Return migration

[edit]In regards to return-migration, many Turkish nationals and Turkish Germans have also migrated from Germany to Turkey, for retirement or professional reasons. Official German records show that there are 2.8 million "returnees"; however, the German Embassy in Ankara estimates the true number to be four million, acknowledging the differences in German official data and the realities of the under-reporting by migrants.[103]

Integration

[edit]

Turkish immigrants make up Germany's largest immigrant group and have been ranked last in Berlin Institute's integration ranking.[104][105]

During a speech in Düsseldorf in 2011, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan urged Turks in Germany to integrate, but not assimilate, a statement that caused a political outcry in Germany.[106]

The Turks in Turkey (especially more progressive-leaning, and those from large cities like Istanbul) can occasionally have somewhat negative views of the Turks in Germany, specifically (descendants of) the first Turkish Gastarbeiters, for their generally more conservative/Islamist political views, sometimes they are called almancı (literal translation "german-er", Almanya meaning "Germany" in Turkish). They are sometimes regarded as "having insufficiently assimilated by the Germans, yet having excessively assimilated by the Turks in the homeland".[107]

Citizenship

[edit]For decades Turkish citizens in Germany were unable to become German citizens because of the traditional German construct of "nationhood". The legal notion of citizenship was based on "blood ties" of a German parent (jus sanguinis) – as opposed to citizenship based on country of birth and residence (jus soli). This adhered to the political notion that Germany was not a country of immigration.[108] For this reason, only those who were of partial Turkish origin (and had one parent who was ethnically German) could obtain German citizenship.

In 1990 Germany's citizenship law was somewhat relaxed with the introduction of the Foreigner's Law; this gave Turkish workers the right to apply for a permanent residency permit after eight years of living in the country.[109] People of Turkish origin born in Germany, who were also legally "foreign", were given the right to acquire German citizenship at the age of eighteen, provided that they gave up their Turkish citizenship. There was no right to dual citizenship out of fears it would increase the Turkish population in the country. Chancellor Helmut Kohl officially gave this as the main reason for denying dual citizenship in 1997:

If today [1997] we give in to demands for dual citizenship, we would soon have four, five, or six million Turks in Germany, instead of three million – Chancellor Helmut Kohl, in 1997.[110]

However, in 1999 the centre-left government of Gerhard Schröder further liberalised Germany's citizenship laws. Non-citizens became eligible for naturalization after eight years of legal residence in the country, and children born in Germany to foreign parents automatically became citizens if at least one had been a permanent resident for at least eight years. Such children also gained a right to dual citizenship until the age of 23, at which point they had to choose between their German citizenship or the citizenship of their parent's country of birth.[111] Former Turkish citizens who have given up their citizenship can apply for the 'Blue Card' (Mavi Kart), which gives them some rights in Turkey, such as the right to live and work in Turkey, the right to possess and inherit land or the right to inherit, but not the right to vote.

In 2000, the year following the citizenship reform, a then-record 187,000 people were naturalised in Germany,[112] 44% (83,000) of whom were of Turkish origin. Over the following two decades, a further 630,000 Turkish people took German citizenship.[113] By 2011 the Embassy of Germany, Washington, D.C. reported that as of 2005 there were 2 million Turks who already had German citizenship.[114]

Culture

[edit]The Turkish people who immigrated to Germany brought their culture with them, including their language, religion, food, and arts. These cultural traditions have also been passed down to their descendants who maintain these values. Consequently, Turkish Germans have also exposed their culture to the greater German society. Numerous Turkish restaurants, grocery stores, teahouses, and mosques are scattered across Germany. The Turks in Germany have also been exposed to German culture, which has influenced the Turkish dialect spoken by the Turkish community in Germany.[citation needed]

Food

[edit]

Turkish cuisine first arrived in Germany during the sixteenth century and was consumed among aristocratic circles.[115] However, Turkish food became available to the greater German society from the mid-twentieth century onwards with the arrival of Turkish immigrants. By the early 1970s Turks began to open fast-food restaurants serving popular kebap dishes. Today there are Turkish restaurants scattered throughout the country selling popular dishes like döner kebap in take-away stalls to more authentic domestic foods in family-run restaurants. Since the 1970s, Turks have opened grocery stores and open-air markets where they sell ingredients suitable for Turkish home-cooking, such as spices, fruits, and vegetables.[citation needed]

Language

[edit]

Turkish is the second most spoken language in Germany, after German. It was brought to the country by Turkish immigrants who spoke it as their first language. These immigrants mainly learned German through employment, mass media, and social settings, and it has now become a second language for many of them. Nonetheless, most Turkish immigrants have passed down their mother tongue to their children and descendants. In general, Turkish Germans become bilingual at an early age, learning Turkish at home and German in state schools; thereafter, a dialectal variety often remains in their repertoire of both languages.[116]

Turkish Germans mainly speak the German language more fluently than their "domestic"-style Turkish language. Consequently, they often speak the Turkish language with a German accent or a modelled German dialect.[117] It is also common within the community to modify the Turkish language by adding German grammatical and syntactical structures. Parents generally encourage their children to improve their Turkish language skills further by attending private Turkish classes or choosing Turkish as a subject at school. In some states of Germany the Turkish language has even been approved as a subject to be studied for the Abitur.[117]

Turkish has also been influential in greater German society. For example, advertisements and banners in public spaces can be found written in Turkish. Hence, it is also familiar to other ethnic groups – it can even serve as a vernacular for some non-Turkish children and adolescents in urban neighborhoods with dominant Turkish communities.[118]

It is also common within the Turkish community to code-switch between the German and Turkish languages. By the early 1990s a new sociolect called Kanak Sprak or Türkendeutsch was coined by the Turkish-German author Feridun Zaimoğlu to refer to the German "ghetto" dialect spoken by the Turkish youth. However, with the developing formation of a Turkish middle class in Germany, there is an increasing number of people of Turkish-origin who are proficient in using the standard German language, particularly in academia and the arts.[116]

Religion

[edit]

The Turkish people in Germany are predominantly Muslim and form the largest ethnic group which practices Islam in Germany.[119] Since the 1960s, "Turkish" was seen as synonymous with "Muslim"; this is because Islam is considered to have a "Turkish character" in Germany.[120][121] This Turkish character is particularly evident in the Ottoman/Turkish-style architecture of many mosques scattered across Germany. In 2016, approximately 2,000 of Germany's 3,000 mosques were Turkish, of which 900 were financed by the Diyanet İşleri Türk-İslam Birliği (DİTİB), an arm of the Turkish government, and the remainder by other political Turkish groups.[122] There is an ethnic Turkish Christian community in Germany; most of them came from recent Muslim Turkish backgrounds.[3] Germany's biggest mosque, the Cologne Central Mosque, was commissioned by DİTİB and completed in 2017. It is also the biggest European mosque outside of Turkey.[123]

Discrimination and anti-Turkism

[edit]Discrimination

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

In 1985 the German journalist Günter Wallraff shocked the German public with his internationally successful book Ganz unten ('In the Pits' or 'Way Down') in which he reported the discrimination faced by Turkish people in German society. He disguised himself as a Turkish worker called "Ali Levent" for over two years and took on minimal-wage jobs and confronted German institutions. He found that many employers did not register or insure their Turkish workers. Major employers like Thyssen did not give their Turkish workers adequate breaks and did not pay them their full wage.[124]

It has been, and still is, also reported that Turkish-Germans were being discriminated against at school from early age and in workplaces. It has also been found that teachers discriminate against non-German sounding names and tend to give worse grades based on names alone. The studies showed that even though a student might have had the exact number of right and wrong answers, or the exact paper, the teachers favour German names. This creates a vicious cycle where teachers favour students of German descent over non-Germans, including Turkish students, which results in worse education. This later results in Turkish people not being able to take what are deemed to be "higher-skill jobs", which nonetheless deepens the cracks in the cycle. [citation needed]

There are also the reports of discrimination against Turkish-Germans in other areas such as sports, one example being the discrimination against the football player Mesut Özil.[citation needed]

Attacks against the Turkish community in Germany

[edit]

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the reunification of Germany, saw a sharp rise in violent attacks against Turkish-Germans.[citation needed] A series of arson attacks, bombings, and shootings have targeted the Turkish community in both public and private spaces, such as in their homes, cultural centres, and businesses. Consequently, many victims have been killed or severely injured by these attacks.

On 27 October 1991, Mete Ekşi, a 19-year-old student from Kreuzberg, along with his four Turkish friends were involved in a violent confrontation with three German brothers.[126] As a consequence, Ekşi died due to head injuries caused with a baseball bat which was wrested by the 25-year-old attacker from Ekşi's friend.[126] His death sparked a massive outrage in the local Turkish community alleging fascist motives.[126] This was, however, dismissed by a court as an "overreaction" while acknowledging and condemning open and hidden xenophobia in Germany.[126] His funeral in November 1991 was attended by 5,000 people.[127]

A year after Ekşi's murder, on 22 November 1992, two Turkish girls, Ayşe Yılmaz and Yeliz Arslan, and their grandmother, Bahide Arslan, were killed by two neo-Nazis in an arson attack in their home in Mölln.[128][129]

On 9 March 1993, Mustafa Demiral, aged 56, was attacked by two members of the German anti-immigrant political party "The Republicans" whilst waiting at a bus stop in Mülheim. The attackers verbally assaulted him prompting a defensive reaction after which one of the attackers threatened him with a gun pointing at his head. Demiral suffered a heart-attack and died at the scene of the crime.[130]

Two months later, on 28 May 1993, four young neo-Nazi German men aged 16–23 set fire to the house of a Turkish family in Solingen. Three girls and two women died and 14 other members of the extended family were severely injured in the attack. German Chancellor Helmut Kohl did not attend the memorial services.

Neo-Nazi attacks continued throughout the 1990s. On 18 February 1994, the Bayram family were attacked on their doorstep by a neo-Nazi neighbour in Darmstadt. The attack was not well publicised until one of the victims, Aslı Bayram, was crowned Miss Germany in 2005. The armed neo-Nazi neighbour shot Aslı on her left arm and then the attacker shot Aslı's father, Ali Bayram, who died from the gunshot.[131]

Between 2000 and 2006 several Turkish shopkeepers were attacked in numerous cities in Germany. The attacks were called the "Bosphorus serial murders" (Mordserie Bosporus) by the German authorities or pejoratively "Kebab murders" (Döner-Morde) by the press – which saw eight Turkish and one Greek person killed. Initially, the German media suspected that Turkish gangs were behind these murders. However, by 2011 it came to light that the perpetrators were in fact the neo-Nazi group the National Socialist Underground.[132] This neo-Nazi group was also responsible for the June 2004 Cologne bombing which resulted in 22 Turkish people being injured.[133]

On 3 February 2008, nine Turkish people, including five children, died in a blaze in Ludwigshafen (de).[128] While there have been speculations by the Turkish media about the origin of the fire suspecting an arson attack and allegations of slow fire response time,[134] these were rejected by an investigation and the cause of the fire was determined to have been an electrical fault. Nevertheless, many German and Turkish politicians including Turkish prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan together with locally elected MP of the German parliament and appointed Minister of State for Integration in the Federal Chancellery and German Federal Government Commissioner for Migration, Refugees and Integration Maria Böhmer or Minister President of Rhineland-Palatinate Kurt Beck visited the site to express their condolences.[135] Chancellor Angela Merkel was criticised for not attending a demonstration held in memory of the victims by 16,000 people.[128]

Not all attacks on Turks have been perpetrated by neo-Nazi right-wing Germans: for example, the perpetrator of a mass shooting in Munich on 22 July 2016 who deliberately targeted people of Turkish and Arab origin. On that day, he killed nine victims, of which four victims were of Turkish origin: Can Leyla, aged 14, Selçuk Kılıç, aged 17, and Sevda Dağ, aged 45;[136] as well as Hüseyin Dayıcık, aged 19, who was a Greek national of Turkish origin.[137]

On 19 February 2020, a German neo-Nazi who expressed hate for non-German people, carried out two mass shootings in the city of Hanau, killing nine foreigners. He then returned to his home, killed his mother and committed suicide. Five of the nine victims were Turkish citizens.[138]

On 2 April 2020, in Hamburg, a German family of Turkish descent claimed to have received a threatening letter with xenophobic content allegedly containing the coronavirus.[139]

Crime

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

Turkish gangs

[edit]In 2014, the annual report into organized crime, presented in Berlin by interior minister Thomas de Maizière, showed that there were 57 Turkish gangs in Germany. In 2016, the Die Welt and Bild reported that new Turkish motorbike gang, the Osmanen Germania is growing rapidly. The Hannoversche Allgemeine newspaper claimed that the Osmanen Germania is advancing more and more into red-light districts, which increases the likelihood of a bloody territorial battle with established gangs like the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club.[140]

Turkish ultra-nationalist movements

[edit]As a result of the immigration wave in the 1960s and 1970s, far right and ultranationalist organisations established themselves in Germany such as the Grey Wolves, Türkische Föderation der Idealistenvereine in Deutschland, Europäisch-Türkische Union (ATB) and Türkisch Islamische Union Europa (ATIB). In 2017, ATB and ATIB together had about 303 locations with 18,500 members.[141]

Popular culture

[edit]Media

[edit]Films

[edit]The first phase in Turkish-German Cinema began in the 1970s and lasted through to the 1980s; it involved writers placing much of their attention on story-lines that represented the living and working conditions of the Turkish immigrant workers in Germany. By the 1990s a second phase shifted towards focusing more on mass entertainment and involved the work of Turkish and German-born Turkish German filmmakers. Critical engagements in story-telling increased further by the turn of the twenty-first century. Numerous films of the 1990s onwards launched the careers of many film directors, writers, and actors and actresses.[142]

Fatih Akin's films, which often examine the place of the Turkish diaspora in Germany, have won numerous awards and have launched the careers of many of its cast including Short Sharp Shock (1998) starring Mehmet Kurtuluş and İdil Üner; Head-On (2004) starring Birol Ünel and Sibel Kekilli; Kebab Connection (2004) starring Denis Moschitto; The Edge of Heaven (2007) starring Baki Davrak; and Soul Kitchen (2009) starring Birol Ünel.

Other notable films which have a transnational context include Feridun Zaimoğlu's book-turned-film Kanak Attack (2000); Kerim Pamuk's Süperseks (2004); and Özgür Yıldırım's Chiko (2008).[145] Several Turkish-German comedy films have also intentionally used comical stereotypes to encourage its viewers to question their preconceived ideas of "the Other", such as Züli Aladağ's film 300 Worte Deutsch ("300 words of German", 2013), starring Almila Bagriacik, Arzu Bazman, Aykut Kayacık, and Vedat Erincin.[146] Similarly, other recent Turkish-German comedies like Meine verrückte türkische Hochzeit (Kiss me Kismet, 2006), starring Hilmi Sözer, Ercan Özçelik, Aykut Kayacık, and Özay Fecht, and the film Evet, I Do! (2009), starring numerous Turkish-German actors such as Demir Gökgöl, Emine Sevgi Özdamar, Erden Alkan, Gandi Mukli, Hülya Duyar, Jale Arıkan, Lilay Huser, Meral Perin, Mürtüz Yolcu, Sema Meray, and Sinan Akkuş, have emphasised how the Turkish and German cultures come together in contemporary German society. By focusing on similarities and differences of the two cultures using comedy, these films have shifted from the earlier Turkish-German drama films of the 1980s which focused on culture clashes; in its place, these films have celebrated integration and interethnic romance.[147]

By 2011 Yasemin Şamdereli and Nesrin Şamdereli's comedy film Almanya: Welcome to Germany, starring Aylin Tezel and Fahri Yardım, premiered at the Berlin Film Festival and was attended by the German President and the Turkish Ambassador to celebrate fifty years since the mass migration of Turkish workers to Germany. Indeed, stories confronting Turkish labour migration, and debates about integration, multiculturalism, and identity, are reoccurring themes in Turkish-German cinema.[148]

Nonetheless, not all films directed, produced or written by Turkish Germans are necessarily about the "Turkish-experience" in Germany. Several Turkish Germans have been involved in other genres, such as Bülent Akinci who directed the German drama Running on Empty (2006),[149] Mennan Yapo who has directed the American supernatural thriller Premonition (2007),[150] and Thomas Arslan who directed the German Western film Gold (2013).[151]

Several Turkish-origin actors from Germany have also starred in Turkish films, such as Haluk Piyes who starred in O da beni seviyor (2001).[152]

Television

[edit]

In the first decade of the twenty-first century several German television series in which the experience of Turkish-Germans as a major theme gained popularity in Germany and in some cases gained popularity abroad too. For example, Sinan Toprak ist der Unbestechliche ("Sinan Toprak is the Incorruptible", 2001–2002) and Mordkommission Istanbul ("Homicide Unit Istanbul", 2008–present) which both star Erol Sander.[155] In 2005 Tevfik Başer's book Zwischen Gott und Erde ("Time of Wishes") was turned into a primetime TV German movie starring Erhan Emre, Lale Yavaş, Tim Seyfi, and Hilmi Sözer, and won the prestigious Adolf Grimme Prize. Another popular Turkish-German TV series was Alle lieben Jimmy ("Everybody Loves Jimmy", 2006–2007) starring Eralp Uzun and Gülcan Kamps.[156] Due to the success of Alle lieben Jimmy, it was made into a Turkish series called Cemil oldu Jimmy – making it the first German series to be exported to Turkey.[157]

By 2006 the award-winning German television comedy-drama series Türkisch für Anfänger ('Turkish for Beginners', 2006–2009) became one of the most popular shows in Germany. The critically acclaimed series was also shown in more than 70 other countries.[158] Created by Bora Dağtekin, the plot is based on interethnic-relations between German and Turkish people. Adnan Maral plays the role of a widower of two children who marries an ethnic German mother of two children – forming the Öztürk-Schneider family. The comedy consisted of fifty-two episodes and three seasons.[159] By 2012 Turkish for Beginners was made into a feature film; it was the most successful German film of the year with an audience of 2.5 million.[160]

Other notable Turkish-origin actors on German television include Erdoğan Atalay,[161] Erkan Gündüz, İsmail Deniz, Olgu Caglar,[162] Özgür Özata,[163] Taner Sahintürk, and Timur Ülker.

Whilst Turkish-origin journalists are still underrepresented, several have made successful careers as reporters and TV presenters including Erkan Arikan[164] and Nazan Eckes.[164]

Many Turkish Germans have also starred in numerous critically acclaimed Turkish drama series. For example, numerous actors and actresses in Muhteşem Yüzyıl were born in Germany, including Meryem Uzerli,[165] Nur Fettahoğlu,[166] Selma Ergeç,[167] and Ozan Güven.[168] Other popular Turkish-German performers in Turkey include Fahriye Evcen who has starred in Yaprak Dökümü and Kurt Seyit ve Şura.[169]

Comedy

[edit]

One of the first comedians of Turkish origin to begin a career as a mainstream comedian is Django Asül who began his career in satire in the 1990s.[170] Another very successful comedian is Bülent Ceylan, who performed his first solo show "Doner for one" in 2002. By 2011 the broadcasting agency RTL aired Ceylan's own comedy show The Bulent Ceylan Show.[170] Other notable comedians include Özcan Cosar, Fatih Çevikkollu,[170] Murat Topal,[170] Serdar Somuncu,[170] Kaya Yanar,[170] and female comedian Idil Baydar.[170]

Literature

[edit]Since the 1960s Turkish people in Germany have produced a range of literature. Their work became widely available from the late 1970s onwards, when Turkish-origin writers began to gain sponsorships by German institutions and major publishing houses.[171] Some of the most notable writers of Turkish origin in Germany include Akif Pirinçci,[171] Alev Tekinay,[171] Emine Sevgi Özdamar,[171] Feridun Zaimoğlu,[171] Necla Kelek,[171] Renan Demirkan,[171] and Zafer Şenocak.[171] These writers approach a broad range of historical, social and political issues, such as identity, gender, racism, and language. In particular, German audiences have often been captivated by Oriental depictions of the Turkish community.

Music

[edit]In the mid-twentieth century the Turkish immigrant community in Germany mostly followed the music industry in Turkey, particularly pop music and Turkish folk music. Hence, the Turkish music industry became very profitable in Germany. By the 1970s, the "arabesque" genre erupted in Turkey and became particularly popular among Turks in Germany. These songs were often played and sang by the Turkish community in Germany in coffee houses and taverns that replicated those in Turkey. These spaces also provided the first stage for semi-professional and professional musicians. Consequently, by the end of the 1960s, some Turks in Germany began to produce their own music, such as Metin Türköz who took up themes of the Turkish immigration journey and their working conditions.[172]

By the 1990s the Turkish Germans became more influential in the music industry in both Germany and Turkey. In general, many Turkish Germans were brought up listening to Turkish pop music, which greatly influenced the music they began to produce. They were also influenced by hip-hop music and rap music.

Since the 1990s, the Turkish-German music scene has developed creative and successful new styles, such as "Oriental pop and rap" and "R'n'Besk" – a fusion of Turkish arabesque songs and R&B music. Examples of Oriental-pop and rap emerged in the early 2000s with Bassturk's first single "Yana Yana" ("Side by Side").[174] The "R'n'Besk"-style gained popularity in Germany with Muhabbet's 2005 single "Sie liegt in meinen Armen" ("She lies in my Arms").[175] By 2007 Muhabbet released the song "Deutschland" ("Germany"); the lyrics appeal to Germans to finally accept the Turkish immigrants living in the country.[176]

In 2015 several Turkish-German musicians released the song "Sen de bizdensin" ("You are one of us"). The vocalists included Eko Fresh, Elif Batman, Mehtab Guitar, Özlem Özdil, and Volkan Baydar. Dergin Tokmak, Ercandize, Serdar Bogatekin, and Zafer Kurus were also involved in the production.[177] The song was used in a campaign to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Ay Yildiz telephone network and was extensively broadcast on TV and radio.[178] Thereafter, a competition and group was formed called Die Stimme einer neuen Ära/Yeni neslin sesi ("The voice of the new generation") to find new Turkish-German talent and "Sen de bizdensin" was re-released with different lyrics.[179][180]

Other Turkish-origin musicians in the German music industry include Bahar Kızıl (from the former girl-group Monrose),[173] and winner of Germany's "Star Search" Martin Kesici.[181]

Several Turkish-origin singers born in Germany have also launched their careers in Turkey, such as Akın Eldes,[182] Aylin Aslım,[183] Doğuş,[184] İsmail YK,[185] Ozan Musluoğlu,[186] Pamela Spence,[187] and Tarkan.[188] The German-born Turkish Cypriot pianist Rüya Taner has also launched her career in Turkey.[189]

There are also some musicians who perform and produce songs in the English language, such as Alev Lenz,[190] DJ Quicksilver,[191] DJ Sakin,[192] and Mousse T.[193]

Rappers

[edit]Especially in the 1990s, Turkish-German rap groups have sold hundreds of thousands of albums and singles in Turkey, telling their stories of integration and assimilation struggles they experienced due to discrimination they faced during their upbringing in Germany.[194][195]

Sports

[edit]Football

[edit]

Men's football

[edit]Many football players of Turkish origin in Germany have been successful in first-division Germany and Turkey football clubs, as well as other European clubs. However, in regards to playing for national teams, many players of Turkish origin who were born in Germany have chosen to play for the Turkey national football team. Nonetheless, in recent years there has been an increase in the number of players choosing to represent Germany.

The first person of Turkish descent to play for the Germany national football team was Mehmet Scholl in 1993,[196] followed by Mustafa Doğan in 1999 and Malik Fathi in 2006.[196] Since the twenty-first century there has been an increase in German-born individuals of Turkish origin opting to play for Germany, including Serdar Tasci[197] and Suat Serdar, Kerem Demirbay,[198] Emre Can,[199] İlkay Gündoğan,[199] Mesut Özil,.[199] Of those, Mesut Özil played the most matches for Germany (92 apps). His photo with Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (together with Ilkay Gündogan and Cenk Tosun) just before the World Cup 2018 and his subsequent retirement after World Cup led to a controversy as well as political and social discussion. In his retirement statement, Özil also reported about racism experiences after his photo with Erdoğan.

Those who have chosen to retain their Turkish citizenship and who have competed for Turkey include Cenk Tosun,[197] Ceyhun Gülselam,[197] Gökhan Töre,[199] Hakan Balta,[196] Hakan Çalhanoğlu,[199] Halil Altıntop,[196] Hamit Altıntop,[196] İlhan Mansız,[200] Nuri Şahin,[196] Ogün Temizkanoğlu,[200] Olcay Şahan,[199] Mehmet Ekici,[197] Serhat Akin,[197] Tayfun Korkut,[200] Tayfur Havutçu,[200] Tunay Torun,[197] Ümit Davala,[200] Umit Karan,[200] Volkan Arslan,[197] Yıldıray Baştürk,[200] Yunus Mallı,[199] Kaan Ayhan, Ahmed Kutucu, Levin Öztunalı, Kenan Karaman, Ömer Toprak, Salih Özcan, Nazim Sangaré, Güven Yalçın, Berkay Özcan and Hasan Ali Kaldırım.

Many Turkish Germans have also played for other national football teams; for example, Turkish German football players in the Azerbaijan national football team include Ufuk Budak, Tuğrul Erat, Ali Gökdemir, Taşkın İlter, Cihan Özkara, Uğur Pamuk, Fatih Şanlı, and Timur Temeltaş.[201]

Several Turkish-German professional football players have also continued their careers as football managers such as Onur Cinel, Kenan Kocak, Hüseyin Eroğlu, Tayfun Korkut and Eddy Sözer. In addition, there are also several Turkish-German referees, including Deniz Aytekin.

Women's football

[edit]In regards to women's football, several players have chosen to play for the Turkish women's national football team, including Aylin Yaren,[202] Aycan Yanaç, Melike Pekel, Dilan Ağgül, Selin Dişli, Arzu Karabulut, Ecem Cumert, Fatma Kara, Fatma Işık, Ebru Uzungüney and Feride Bakır.

There are also players who plays for the German women's football national football team, including Sara Doorsoun, Hasret Kayıkçı and Alara Şehitler.

Turkish-German football clubs

[edit]The Turkish community in Germany has also been active in establishing their own football clubs such as Berlin Türkspor 1965 (established in 1965) and Türkiyemspor Berlin (established in 1978). Türkiyemspor Berlin were the Champions in the Berlin-Liga in the year 2000. They were the winners of the Berliner Landespokal in 1988, 1990, and 1991. Türkgücü München, established in 1975, play in the 3. Liga.

Politics

[edit]

German politics

[edit]The Turks in Germany began to be active in politics by establishing associations and federations in the 1960s and 1970s – though these were mainly based on Turkish politics rather than German politics. The first significant step towards active German politics occurred in 1987 when Sevim Çelebi became the first person of Turkish origin to be elected as an MP in the West Berlin Parliament.[204]

With the reunification of East Germany and West Germany, unemployment in the country had increased and some political parties, particularly the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), used anti-immigration discourses as a political tool in their campaigns. To counter this, many people of Turkish origin became more politically active and began to work in local elections and in the young branches of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the Green Party. Several associations were founded by almost all German parties to organise meetings for Turkish voters. This played an important gateway for those who aspired to become politicians.[204]

Federal Parliament

[edit]

In 1994 Leyla Onur from the SPD and Cem Özdemir from the Green Party became MPs in the Federal Parliament. They were both re-elected in the 1998 elections and were joined by Ekin Deligöz from the Green party. Deligöz and Özdemir were both re-elected as MPs for the Greens and Lale Akgün was elected as an MP for the SPD in the 2002 elections. Thereafter, Deligöz and Akgün were successful in being re-elected in the 2005 elections; the two female politicians were joined by Hakkı Keskin who was elected as an MP for the Left Party.[206]

By the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, the number of German MPs of Turkish origin remained similar to the previous elections. In the 2009 elections Ekin Deligöz and Mehmet Kılıç were elected for the Greens, Aydan Özoğuz for the SPD, and Serkan Tören for the FDP.[206] Nonetheless, several Turkish-origin politicians were successful in becoming ministers and co-chairs of political parties. For example, in 2008 Cem Özdemir became the co-chair of the Green Party. In 2010 Aygül Özkan was appointed as the Women, Family, Health and Integration Minister, making her the first ever minister of Turkish origin or the Muslim faith. In the same year, Aydan Özoğuz was elected as deputy chairperson of the SPD party. By 2011, Bilkay Öney from the SPD was appointed as Integration Minister in the Baden-Württemberg State.[207]

Since the 2013 German elections, Turkish-origin MPs have been elected into Federal Parliament from four different parties. Cemile Giousouf, whose parents immigrated from Greece, became the first person of Western Thracian Turkish-origin to become an MP. Giousouf was the first Turkish-origin MP and first Muslim to be elected from the CDU party.[208] Five MPs of Turkish-origin were elected from the SPD party including Aydan Özoğuz, Cansel Kiziltepe, Gülistan Yüksel, Metin Hakverdi and Mahmut Özdemir. Özdemir, at the time of his election, became the youngest MP in the German Parliament.[209][210] For the Green Party, Cem Özdemir, Ekin Deligöz and Özcan Mutlu were elected as MPs, and Azize Tank for the Left Party.[211]

European Parliament

[edit]In 1989 Leyla Onur from the SPD party was the first person of Turkish-origin to be a member of the European Parliament for Germany.[212] By 2004 Cem Özdemir and Vural Öger also became members of the European Parliament. Since then, Ismail Ertug was elected as a Member of the European Parliament in 2009 and was re-elected in 2014.[213]

Turkish-German political parties

[edit]| Political parties in Germany | Year established | Founders | Current Leader | Position | Ideologies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative for Migrants (German: Alternative für Migranten, AfM; Turkish: Göçmenler için Alternatif) |

2019 | Turkish and Muslim minority interests | |||

| Alliance for Innovation and Justice (German: Bündnis für Innovation und Gerechtigkeit, BIG; Turkish: Yenilik ve Adalet Birliği Partisi) |

2010 | Haluk Yıldız | Haluk Yıldız | Turkish and Muslim minority interests | |

| Alliance of German Democrats (German: Allianz Deutscher Demokraten, ADD; Turkish: Alman Demokratlar İttifakı) |

26 June 2016[214] | Remzi Aru | Ramazan Akbaş | Turkish and Muslim minority interests, Conservatism | |

| Bremen Integration Party of Germany (German: Bremische Integrations-Partei Deutschlands, BIP; Turkish: Almanya Bremen Entegrasyon Partisi) |

2010 | Levet Albayrak | Turkish and Muslim minority interests |

Turkish politics

[edit]Some Turks born or raised in Germany have entered Turkish politics. For example, Siegen-born, Justice and Development Party (AKP) affiliated Akif Çağatay Kılıç has been the Minister of Youth and Sports of Turkey since 2013.[215]

Germany is effectively Turkey's 4th largest electoral district. Around a third of this constituency vote in Turkish elections (570,000 in the 2015 parliamentary elections), and the share of conservative votes for the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is even higher than in Turkey itself.[216] Following the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt, huge pro-Erdogan demonstrations were held by Turkish citizens in German cities.[216] The Economist suggested that this would make it difficult for Germany politicians to criticize Erdogan's policies and tactics.[216] However, equally huge demonstrations by Turkish Kurds were also held in Germany some weeks later against Erdogan's 2016 Turkish purges and against the detention the HDP party co-chairpersons Selahattin Demirtaş and Figen Yüksekdağ in Turkey.[217]

Notable people

[edit]

See also

[edit]- List of Turkish Germans

- List of German locations named after people and places of Turkish origin

- Turks in Berlin

- Germany–Turkey relations

- Turkish diaspora

References

[edit]- ^ "Infographic: Europe's Turkish Communities". 11 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Bevölkerung in Privathaushalten nach Migrationshintergrund im weiteren Sinn nach ausgewählten Geburtsstaaten". Fedeal Statistical Office of Germany. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ a b Esra Özyürek (6 August 2016). "Convert Alert: German Muslims and Turkish Christians as Threats to Security in the New Europe". Cambridge University Press. 51 (1): 91–116. JSTOR 27563732. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ Özyürek, Esra. 2005. "The Politics of Cultural Unification, Secularism, and the Place of Islam in the New Europe." American Ethnologist 32 (4): 509–12.

- ^ Horrocks & Kolinsky 1996, 17.

- ^ a b c d e f Engelmann, Bernt [in German] (1991), Du deutsch?: Geschichte der Ausländer in Deutschland, Steidl, p. 59, ISBN 9783882431858,

...die er taufen ließ und zur Ehefrau nahm , und fast jeder der heimkehrenden Barone und Grafen hatte Kriegsgefangene in seinem Gefolge...Der deutsche Dichterfürst mit orientalischen Vorfahren stellt indessen keineswegs eine seltene Ausnahme dar.

- ^ a b Acevit, Ayşegül (2020), Beutetürken – Die muslimischen Vorfahren der Deutschen (PDF), Westdeutscher Rundfunk, pp. 8–9, retrieved 19 April 2021

- ^ Hauser, Françoise (2016), 111 Orte im Heilbronner Land, die man gesehen haben muss: Reiseführer, Emons Verlag, ISBN 9783960410522,

Die Herren von Magenheim (nach anderen Quellen war es Reinhard von Württemberg) beispielsweise verschleppten einen türkischen Kriegsgefangenen und nahmen ihn mit auf ihre Burg in Cleebronn: Sadok Seli Soltan sollte der erste Deutsch-Türke werden. Um die 30 Jahre alt dürfte er gewesen sein, als er sich zwangsweise in Deutschland niederließ.

- ^ Goethe, der Beutetürke?, Kandil, 2016, retrieved 26 March 2021,

Und doch gibt es unter Goethes Vorfahren mütterlicherseits einen Ahnen türkisch-osmanischer, muslimischer Herkunft: Johann Soldan hieß vor seiner christlichen Taufe, die im Jahr 1305 in Brackenheim (Landkreis Heilbronn, Baden-Württemberg) vorgenommen wurde, auf Türkisch vermutlich Mehmet Sadık Selim Sultan. Überliefert in deutschen Quellen ist der Name als "Sadok Seli Soltan". Johann Soldan jedenfalls starb 1328 und gilt als der erste urkundlich erfasste Deutsche türkischer Herkunft.

- ^ a b Mommsen, Katharina [in German] (2015), "Goethe'nin Damarlarındaki Türk kanı", »Oient und Okzident sind nicht mehr zu trennen«: Goethe und die Weltkulturen ["Garb ve Şark Artık Ayrılmazlar." Goethe ve Dünya Kültürleri], translated by Özkan, Senail [in Turkish], Ötüken, pp. 297–304, ISBN 9786051553115

- ^ Kraemer, Hermann (1913), Aus biologie, tierzucht und rassengeschichte: Gesammelte vorträge und aufsätze, Volume 2, E. Ulmer, p. 184,

...die Familie Soldan untersucht , die in Südwestdeutschland eine größere Verbreitung besißt. Diese Familie stammt von einem türkischen Offizier , der in den Kreuzzügen gefangen und nach Deutschland gebracht wurde . Seit 600 Jahren haben sich unter den Nachkommen dieses hochbegabten Mannes auffallend viele als Gelehrte ...

- ^ Kippenberg, Anton [in German] (1928), Jahrbuch der sammlung Kippenberg, vol. 7, Insel Verlag, pp. 304–306, ISBN 9783960410522

- ^ Leiprecht, Rudolf [in German] (2005), Schule in der Einwanderungsgesellschaft: ein Handbuch, Wochenschau Verlag, p. 29, ISBN 9783879202744,

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , einen fremdländischen Vorfahren : Er soll von dem türkischen Offizier Sadok Seli Zoltan abstammen , den Graf Reinhart von Württemberg im Jahre 1291 von einem der Kreuzzüge aus dem Heiligen Land mit nach Süddeutschland gebracht hatte

- ^ Frels, Wilhelm [in German] (1929), "Goethe-Schrifttum. Berichtszeit Februar 1928", Jahrbuch der Goethe-Gesellschaft, 15, Goethe-Gesellschaft: 259,

Goethes Verwandtschaft mit der Familie Soldan , die angeblich von einem kriegsgefangenen Türken Sadoch Selim Soldan abstammt.

- ^ Meier-Braun, Karl-Heinz [in German] (2017), Die 101 wichtigsten Fragen: Einwanderung und Asyl, C.H. Beck, ISBN 9783406710889,

Dass Johann Wolfgang von Goethe türkische Vorfahren hatte, war bekannt. Dass diese Wurzeln jedoch nach Baden-Württemberg zurückreichen, weniger. Das hat jedenfalls der Brackenheimer Dekan Werner-Ulrich Deetjen herausgefunden Laut dem promovierten Kirchenhistoriker gehen Goethes Vorfahren auf Sadok Selim zurück, der gegen Ende des 13. Jahrhunderts bei Kämpfen mit Kreuzfahrern im Heiligen Land in die Gefangenschaft des Deutschritterordens geriet.

- ^ Maier, Ulrich [in German] (2002), Fremd bin ich eingezogen: Zuwanderung und Auswanderung in Baden-Württemberg, Bleicher Verlag, p. 27,

Gedachter Johann Soldan heiratete Rebekka Dohlerin... Kein Geringerer als Johann Wolfgang von Goethe zählt diesen ehemaligen türkischen Beamten und Offizier zu seinen Vorfahren

- ^ Hans Soldan, ein engagierter Rechtsanwalt, Soldan, 2009, archived from the original on 24 May 2015, retrieved 19 April 2021,

Die Ursprünge der Familie Soldan reichen bis ins frühe 14. Jahrhundert zurück. Stammvater soll der türkische Offizier Sadok Seli Soltan gewesen sein, der während eines Kreuzzugs vom Grafen von Lechtimor gefangen genommen wurde, der ihn wegen seiner Tapferkeit und besonderen Größe zu einem seiner Obersten ernannte.

- ^ Maria Dusl, Andrea [in German] (2014), Die Leiden des jungen Erdem. War Goethe Türke?, Falter, retrieved 19 April 2021,

Nach Ansicht der Erforscher des Stammbaums vom Herrn Geheimrat hatte dieser zumindest einen türkischen Vorfahren. Über seine Urgroßmutter mütterlicherseits, Elisabeth Katharina Seip (1680-1759), stammt Jowo Goethe von einem gewissen Heinrich Soldan ab, Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts Bürgermeister des hessischen Städtchens Frankenberg. Die (noch heute blühende) Familie Soldan sieht als ihren Stammvater Johann Soldan an, Oberst in Diensten des Grafen von Württemberg. Das türkische daran? Johann Soldan (1270-1328) gilt als der erste urkundlich nachweisbare Türke in Deuschland. Mehmet Sadık Selim Sultan (auch: Sadok Seli Soltan) war türkischer Offizier.

- ^ Sommer, Robert (1907), Familienforschung und Vererbungslehre, Barth, p. 147

- ^ Çelik, Latif (2008), Türkische Spuren in Deutschland / Almanyaʼda Türk Izleri, Logophon Verlag GmbH, p. 202, ISBN 9783936172089

- ^ Selçuklular ve Haçlılar Sempozyumu Başladı, Konya Büyükşehir Belediyesi, 2016, retrieved 18 April 2021

- ^ Çelik 2008, 207.

- ^ a b Wilson, Peter H. (2016), Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire, Harvard University Press, p. 151, ISBN 978-0674058095

- ^ Hannken, Helga (2021), Frauen sind wichtig – Frauen sind nichtig!: Durch Eheschließungen von Angehörigen deutscher Fürstenhäuser zur Macht und Regentschaft in Großbritannien. Von den Tudors über die Stuarts zu den Hannoveranern, LIT Verlag, p. 182, ISBN 9783643146243,

Der eine war Mehmed Ludwig Maximilian von Königstreu (um 1660-1726), Sohn eines türkischen Gouverneurs. Er fiel als Kind 1685 im Türkenkrieg in die Hände der hannoverschen Truppen. Am Hof von Ernst August galt er als exotische...

- ^ Abdullah, Muhammad S. (1981), Geschichte des Islams in Deutschland Volume 5 of Islam und westliche Welt, Styria, p. 182, ISBN 9783222113529,

Es war seinerzeit modisch , junge Türken in Samt und Seide zu kleiden und um sich zu haben . ... Erbprinz Georg Ludwig und sein Bruder Prinz Maximilian brachten demnach zwölf Türkenkinder heim , die am kurfürstlichen Hofe erzogen wurden . ... Da sich dieser Mehmed durch Fleiß und Redlichkeit auszeichnete , wurde er unter dem Namen " Mehmed von Königstreu " vom Kurfürsten in den erblichen ...

- ^ a b c d e Wilson, Peter (2002), German Armies: War and German Society, 1648-1806, Routledge, p. 86, ISBN 978-1135370534

- ^ a b Sulick, Michael J. (2014), Spying in America: Espionage from the Revolutionary War to the Dawn of the Cold War, Georgetown University Press, ISBN 9781626160668,

Karl Boy-Ed was half German and half Turkish and was an experienced naval attaché, if not a professional intelligence officer.

- ^ a b Goebel, Ulrike (2000), German Propaganda in the United States, 1914-1917 -- a Failure?, University of Wisconsin-Madison, p. 16,

Karl Boy-Ed, son of a Turkish father and a German mother, had received a special executive training and had served as naval attaché in several parts of the world.

- ^ a b c Ahmed, Akbar S. (1998), Islam Today: A Short Introduction to the Muslim World, I.B.Tauris, p. 176, ISBN 978-0857713803

- ^ a b c d e f g Nielsen, Jørgen (2004), Muslims in Western Europe, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 2–3, ISBN 978-0-7486-1844-6

- ^ Killy, Walther; Vierhaus, Rudolf (2011), "Rutowsky", Dictionary of German Biography, vol. 8, Walter de Gruyter, p. 509, ISBN 978-3110966305,

As the illegitimate son of King Augustus II of Poland and Elector of Saxony (Frederick Augustus I) and a Turkish woman who later became Frau von Spiegel R. was educated at Parisian and Sardinian courts.

- ^ a b Hohmuth, Jürgen (2003), Dresden Heute, Prestel, p. 64, ISBN 978-3791328607

- ^ Otto Bardon (ed.), Friedrich der Grosse (Darmstadt, 1982) p. 542. Blanning, "Frederick The Great" in Scott (ed.) Enlightment Absolutism pp. 265-288. Christopher Clark, The Iron Kingdom (London 2006), p. 252-3.

- ^ Rosenow-Williams, Kerstin (2012), Organizing Muslims and Integrating Islam in Germany: New Developments in the 21st Century, BRILL, p. 13, ISBN 978-9004230552

- ^ Esposito & Burgat 2003, 232.

- ^ "Heuss-Turks".

- ^ Aktürk, Şener (2010). "The Turkish Minority in German Politics: Trends, Diversification of Representation, and Policy Implications". Insight Turkey. 12 (1): 65–80. JSTOR 26331144.

- ^ Nathans 2004, 242.

- ^ Barbieri 1998, 29.

- ^ Lucassen 2005, 148-149.

- ^ Findley 2005, 220.

- ^ Horrocks & Kolinsky 1996, 89.

- ^ Moch 2003, 187.

- ^ Legge 2003, 30.

- ^ Mitchell 2000, 263.

- ^ Inda & Rosaldo 2008, 188.

- ^ Oğlum seyredip çok eğlenecek, Radika, 2008, retrieved 29 March 2021,

Bizimkiler Bulgaristan göçmeni. Sonra Almanya'ya gitmişler. Ben orada doğmuşum, Nürnberg'de.

- ^ Die neue Leichtigkeit, Sächsische Zeitung, 2015, retrieved 29 March 2021,

Bilgin und Filiz Osmanodja, Geschwister-Paar einer bulgarischen Familie mit türkischen Wurzeln, wohnen nun in einer WG in Berlin-Wilmersdorf.

- ^ Maeva, Mancheva (2011), "Practicing Identities Across Borders: The Case of Bulgarian Turkish Labor Migrants in Germany", in Eade, John; Smith, Michael Peter (eds.), Transnational Ties: Cities, Migrations, and Identities, Transaction Publishers, p. 168, ISBN 978-1412840361

- ^ BalkanEthnology. "BULGARIAN TURKS AND THE EUROPEAN UNION" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ^ Smith, Michael; Eade, John (2008), Transnational Ties: Cities, Migrations, and Identities, Transaction Publishers, pp. 166–179, ISBN 978-1-4128-0806-4.

- ^ "Berlin's unwanted Roma". 14 October 2010.

- ^ a b Maeva, Mila (2007), "Modern Migration waves of Bulgarian Turks", in Marushiakova, Elena (ed.), Dynamics of National Identity and Transnational Identities in the Process of European Integration, Cambridge Scholar Publishing, p. 8, ISBN 978-1847184719

- ^ Maeva, Mila (2011), "Миграция и мобилност на българските турци – преселници в края на ХХ и началото на ХХІ век", Миграции от двете страни на българо-турската граница: наследства, идентичности, интеркултурни взаимодействия., Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Studies with Ethnographic Museum, pp. 49–50, ISBN 978-954-8458-41-2

- ^ Guentcheva, Rossitza; Kabakchieva, Petya; Kolarski, Plamen (September 2003), Migrant Trends in Selected Applicant Countries, VOLUME I – Bulgaria: The social impact of seasonal migration (PDF), Vienna, Austria: International Organization for Migration, p. 44, archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2018

- ^ Viele Debüts im Bundestag: Im neu gewählten Deutschen Bundestag sind elf türkischstämmige Abgeordnete vertreten., Deutschland.de, 2014, retrieved 2 April 2021,

Giousouf ist die erste muslimische Abgeordnete der CDU im Bundestag; ihre Eltern gehören der türkischen Minderheit in der griechischen Region Thrakien an.

- ^ Westerlund & Svanberg 1999, 320-321.

- ^ Whitman, Lois (1990), Destroying Ethnic Identity: The Turks of Greece, Human Rights Watch, pp. 11–12, ISBN 978-0929692708

- ^ a b c Arif, Nazmi (2018), Yunanistan'da, Batı Trakya Türklerinin dış ülkelere göçü endişe ve kaygı verici boyutlara ulaştı., TRT, archived from the original on 14 February 2021, retrieved 12 November 2020

- ^ Şentürk, Cem (2008), "Batı Trakya Türklerin Avrupa'ya Göçleri", Uluslararası Sosyal Aratırmalar Dergisi, 1/2: 420

- ^ Turan, Ömer (2002), "Makedonya'da Türk Varlığı Ve Kültürü", Bilig Türk Dünyası Sosyal Bilimler Dergis, 3 (21–33): 23

- ^ Kuzey Makedonya'daki Nüfus Sayımına Davet: Sonuçlar, Kuzey Makedonya'nın Kurucu Unsuru Türklerin Tapusudur, Tamga Türk, 2021, retrieved 21 May 2021,

Furkan Çako, yurt dışında yaşayan Makedonya Türklerini, ülkedeki nüfus sayımına katılmaya ve kendilerini Türk olarak kaydettirmeye çağırdı. Diplomatımız, Twitter hesabından yaptığı çağrıda şu ifadeleri kullandı: Ülkemizde devam eden #NüfusSayımı2021 sürecine katılmak ve kaydınızı #Türk olarak gerçekleştirmek için yurtdışında yaşayan ve Türkiye, Slovakya, Çek Cumhuriyeti, Almanya, Avusturya, İsviçre, İtalya ve İsveç'te bulunan vatandaşlarımız aşağıdaki bilgilerden yararlanabilirler.

- ^ Catalina Andreea, Mihai (2016), Cultural resilience or the Interethnic Dobrujan Model as a Black Sea alternative to EuroIslam in the Romanian Turkish-Tatar community, University of Bergamo, p. 150

- ^ Rüya Taner, CypNet, retrieved 29 March 2021,

The pianist, who was born in Schwenningen (Germany) in 1971 to Cypriot parents, showed great musical talent at a very young age, and was praised as a child prodigy by many professional musicians.

- ^ a b Vahdettin, Levent; Aksoy, Seçil; Öz, Ulaş; Orhan, Kaan (2016), Three-dimensional cephalometric norms of Turkish Cypriots using CBCT images reconstructed from a volumetric rendering program in vivo, Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey,

Recent estimates suggest that there are now 500,000 Turkish Cypriots living in Turkey, 300,000 in the United Kingdom, 120,000 in Australia, 5000 in the United States, 2000 in Germany, 1800 in Canada, and 1600 in New Zealand with a smaller community in South Africa.

- ^ North Cyprus Missions Abroad, CypNet, retrieved 10 May 2021

- ^ "North Cyprus Representatives Offices Abroad", turkishcyprus.com, retrieved 10 May 2021

- ^ "Turkish migrants grieve for Beirut from exile". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- ^ Barth, Alexander (2018), Schönheit im Wandel der Zeit (Image 45 of 67), Neue Ruhr Zeitung, retrieved 27 March 2021,

Yasemin Mansoor (Jahrgang 1979) ist Miss Germany 1996. Die damals 16-Jährige brach brach den Rekord als jüngste gewinnerin des schönheitswettbewerbs. Später arbeitete die Tochter irakisch-türkischer Immigranten als Fotomodell und produzierte Popmusik mit der Mädchenband "4 Unique...

- ^ ITC Berlin Temsilcisi Türkmeneli gazetesine konuştu: Avrupa'da Türkmen lobisi oluşturmayı hedefliyoruzA, Biz Türkmeniz, 2008, retrieved 11 November 2020

- ^ Avrupa'da Suriyeli Türkmenler İlk Dernek Kurdular Suriye Türkmen kültür ve yardımlaşma Derneği- Avrupa STKYDA, Suriye Türkmenleri, retrieved 10 November 2020

- ^ SYRISCH TURKMENICHER KULTURVEREIN E.V. EUROPA, Suriye Türkmenleri, retrieved 10 November 2020

- ^ de Jong, Petra Wieke (2021), "Patterns and Drivers of Emigration of the Turkish Second Generation in the Netherlands", European Journal of Population, 38 (1), Springer: 15–36, doi:10.1007/s10680-021-09598-w, PMC 8924341, PMID 35370530, S2CID 244511118

- ^ Der Historiker Götz Aly ist Nachfahre des Urtürken, Der Tagesspiegel, 2014, retrieved 26 March 2021,

Genau 102 Nachkommen des ersten Türken in Berlin – sie nennen ihn den "Urtürken" ... Geht man von einer Generationsspanne von durchschnittlich 35 Jahren aus, dann stammen Götz Aly und die anderen in sechster, siebter und achter Generation vom Urtürken ab.

- ^ Engstrom, Aineias (12 January 2021), "Turkish-German "dream team" behind first COVID-19 vaccine", Portland State Vanguard, Portland State University, archived from the original on 27 March 2021, retrieved 27 March 2021,

The German census does not gather data on ethnicity, however according to estimates, somewhere between 4–7 million people with Turkish roots, or 5–9% of the population, live in Germany.

- ^ Bell, David Scott; Pisani, Edgard; Gaffney, John (1990). European Immigration Policy. Vol. 3. Pergamon Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780080413884.

The result is that the two and a half to three million Turks in Germany are not seen as 'immigrants' but as 'guest workers'.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Blank, Stephen; Johnsen, William T.; Pelletiere, Stephen C. (1993). Turkey's Strategic Position at the Crossroads of World Affairs (PDF). Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of Hawaii. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-89875-890-0.

Fourth, the rise of xenophobic groups in Germany that have focused their sometimes deadly attacks on the 1.8 million ethnic Turks living in Germany has also strained relations.

- ^ Yinger, John Milton (1994), Ethnicity: Source of Strength? Source of Conflict?, State University of New York Press, p. 99, ISBN 9780791417973,

Barbara John, a member of the German Government's Special Commission on Integration has observed that.. more than three million are Turkish guest workers and their descendants, some of them third-generation residents of Germany... Each year, about 20,000 of them are nationalized, but 79,000 babies are born...

- ^ Denton, Geoffrey R. (1996), Twenty-first Century Challenges to Europeans: The Modern Horsemen of the Apocalypse, The Stationery Office, p. 18, ISBN 9780117019188,

The law concerning non – Germans was also very liberal until repealed in 1993; three million Turks live in Germany as a consequence of the liberal immigration policy of the 1960s and 1970s.

- ^ Marger, Martin (1997), Race and Ethnic Relations: American and Global Perspectives, Wadsworth Publishing, p. 534, ISBN 9780534505639,

Very few of Germany's three million Turks, for example, have been afforded citizenship, even those who are second – or even third-generation German residents.