Tibetan Empire

This article's lead section may be too long. (June 2023) |

Tibetan Empire བོད་ཆེན་པོ bod chen po | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 618–842/848 | |||||||||||||||

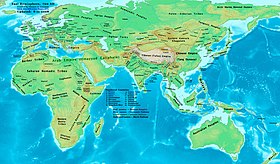

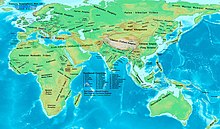

![Map of the Tibetan Empire's influence at its greatest extent, in the late 8th to mid-9th century[1]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/18/Tibetan_empire_greatest_extent_780s-790s_CE.png/250px-Tibetan_empire_greatest_extent_780s-790s_CE.png) Map of the Tibetan Empire's influence at its greatest extent, in the late 8th to mid-9th century[1] | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Lhasa | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Tibetic languages | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Tibetan Buddhism, Bon | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Tsenpo (Chief) | |||||||||||||||

• 618–650 | Songtsen Gampo (first) | ||||||||||||||

• 753–797 | Trisong Detsen | ||||||||||||||

• 815–838 | Ralpachen | ||||||||||||||

• 841–842[2] | U Dum Tsen (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Lönchen (Chief Minister) | |||||||||||||||

• 652–667 | Gar Tongtsen Yülsung | ||||||||||||||

• 685–699 | Gar Trinring Tsendro | ||||||||||||||

• 782?–783 | Nganlam Takdra Lukhong | ||||||||||||||

• 783–796 | Nanam Shang Gyaltsen Lhanang | ||||||||||||||

| Banchenpo (Chief Monk) | |||||||||||||||

• 798–? | Nyang Tingngezin Sangpo (first) | ||||||||||||||

• ?–838 | Dranga Palkye Yongten (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity | ||||||||||||||

• Established | 618 | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 842/848 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 800 est.[3][4] | 4,600,000 km2 (1,800,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 7th–8th century[5] | 10 million | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| History of Tibet |

|---|

|

| See also |

|

|

The Tibetan Empire (Tibetan: བོད་ཆེན་པོ, Wylie: bod chen po, lit. 'Great Tibet'; Chinese: 吐蕃; pinyin: Tǔbō / Tǔfān) was an empire centered on the Tibetan Plateau, formed as a result of imperial expansion under the Yarlung dynasty heralded by its 33rd king, Songtsen Gampo, in the 7th century. The empire further expanded under the 38th king, Trisong Detsen, and expanded to its greatest extent under the 41st king, Rapalchen, whose 821–823 treaty was concluded between the Tibetan Empire and the Tang dynasty. This treaty, inscribed on a pillar at Jokhang, delineated Tibet as being in possession of an area larger than the Tibetan Plateau, stretching east to Chang'an, west beyond modern Afghanistan, south into modern India and the Bay of Bengal.[6]

The Yarlung dynasty was founded in 127 BC in the Yarlung Valley along the Yarlung River, south of Lhasa. The Yarlung capital was moved in the 7th century from the palace Yumbulingka to Lhasa by the 33rd king Songsten Gampo, and into the Red Fort during the imperial period which continued to the 9th century. The beginning of the imperial period is marked in the reign of the 33rd king of the Yarlung dynasty, Songtsen Gampo. The power of Tibet's military empire gradually increased over a diverse terrain. During the reign of Trisong Detsen, the empire became more powerful and increased in size. At this time, a 783 treaty between the Tibetan Empire and the Tang dynasty defined the borders, as commemorated by the Shol Potala Pillar in Lhasa.[7] Borders were again confirmed during the later reign of the 41st king Ralpachen through his 821–823 treaty between the Tibetan Empire and Tang dynasty, which was also commemorated by three inscribed stelae.[8][7] In the opening years of the 9th century, the Tibetan Empire controlled territories extending from the Tarim Basin to the Himalayas and Bengal, and from the Pamirs into what are now the Chinese provinces of Sichuan, Gansu and Yunnan. The murder of King Rapalchen in 838 by his brother Langdarma, and Langdarma's subsequent enthronement[7] followed by his assassination in 842 marks the simultaneous beginning of the dissolution of the empire period.

Before the empire period, sacred Buddhist relics were discovered by the Yarlung dynasty's 28th king, Iha-tho-tho-ri (Thori Nyatsen), and then safeguarded.[9] Later, Tibet marked the advent of its empire period under King Songsten Gampo, while Buddhism initially spread into Tibet after the king's conversion to Buddhism, and during his pursuits in translating Buddhist texts while also developing the Tibetan language.[9] Under King Trisong Detsen, the empire again expanded as the founding of Tibetan Buddhism and the revealing of the Vajrayana by Guru Padmasambhava was occurring.[9]

The empire period then corresponded to the reigns of Tibet's three 'Religious Kings',[7] which includes King Rapalchen's reign. After Rapalchen's murder, King Lang darma nearly destroyed Tibetan Buddhism[7] through his widespread targeting of Nyingma monasteries and monastic practitioners. His undertakings correspond to the subsequent dissolution of the unified empire period, after which semi-autonomous polities of chieftains, minor kings and queens, and those surviving Tibetan Buddhist polities evolved once again into autonomous independent polities, similar to those polities also documented in the Tibetan Empire's nearer frontier region of Do Kham (Amdo and Kham).[10][11]

Other unreferenced ideas about the dissolution of the empire period include: The varied terrain of the empire and the difficulty of transportation, coupled with the new ideas that came into the empire as a result of its expansion, helped to create stresses and power blocs that were often in competition with the ruler at the center of the empire.[according to whom?][citation needed] Thus, for example, adherents of the Bön religion and the supporters of the ancient noble families gradually came to find themselves in competition with the "recently" introduced Tibetan Buddhism.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Namri Songtsen and founding of the dynasty

[edit]

The power that became the Tibetan state originated at the Taktsé Castle (Wylie: Stag-rtse) in the Chingba (Phying-ba) district of Chonggyä (Phyongs-rgyas). There, according to the Old Tibetan Chronicle, a group convinced Tagbu Nyazig (Stag-bu snya-gzigs) to rebel against Gudri Zingpoje (Dgu-gri Zing-po-rje), who was, in turn, a vassal of the Zhangzhung empire under the Lig myi dynasty. The group prevailed against Zingpoje. At this point Namri Songtsen (also known as Namri Löntsän) was the leader of a clan which one by one prevailed over all his neighbouring clans. He besieged the Kingdom of Sumpa in the early 7th century and eventually conquered it. He gained control of all the area around what is now Lhasa, before his assassination around 618. This new-born regional state would later become known as the "Tibetan Empire". The government of Namri Songtsen sent two embassies to the Chinese Sui dynasty in 608 and 609, marking the appearance of Tibet on the international scene.[12]

- "This first mention of the name Bod, the usual name for Tibet in the later Tibetan historical sources, is significant in that it is used to refer to a conquered region. In other words, the ancient name Bod originally referred only to a part of the Tibetan Plateau, a part which, together with Rtsaṅ (Tsang, in Tibetan now spelled Gtsaṅ) has come to be called Dbus-gtsaṅ (Central Tibet)."[13]

Reign of Songtsen Gampo (618–650)

[edit]Songtsen Gampo (Srong-brtsan Sgam-po) (c. 604 – 650) was the first great emperor who expanded Tibet's power beyond Lhasa and the Yarlung Valley, and is traditionally credited with introducing Buddhism to Tibet.

When his father Namri Songtsen died by poisoning (circa 618[14]), Songtsen Gampo took control after putting down a brief rebellion. Songtsen Gampo proved adept at diplomacy as well as combat. The emperor's minister, Myang Mangpoje (Myang Mang-po-rje Zhang-shang), defeated the Sumpa people ca. 627.[15] Six years later (c. 632–33) Myang Mangpoje was accused of treason and executed.[16][17][18] He was succeeded by minister Gar Tongtsen (mgar-stong-btsan).

The Chinese records mention an envoy to Tibet in 634. On that occasion, the Tibetan Emperor requested (demanded according to Tibetan sources) marriage to a Chinese princess but was refused. In 635-36 the Emperor attacked and defeated the Tuyuhun (Tibetan: ‘A zha), who lived around Lake Koko Nur and controlled important trade routes into China. After a series of military campaigns between Tibet and the Tang dynasty in 635-8,[19](see also Tibetan attack on Songzhou)the Chinese emperor agreed (only because of the threat of force, according to Tibetan sources[20]) to provide a Chinese princess to Songtsen Gampo.

Circa 639, after Songtsen Gampo had a dispute with his younger brother Tsänsong (Brtsan-srong), the younger brother was burned to death by his own minister Khäsreg (Mkha’s sregs) (presumably at the behest of his older brother the emperor).[17][18]

The Chinese Princess Wencheng (Tibetan: Mung-chang Kung-co) departed China in 640 to marry Songtsen Gampo's son. She arrived a year later. This is traditionally credited with being the first time that Buddhism came to Tibet, but it is very unlikely Buddhism extended beyond foreigners at the court.

Songtsen Gampo’s sister Sämakar (Sad-mar-kar) was sent to marry Lig-myi-rhya, the king of Zhangzhung in what is now Western Tibet. However, when the king refused to consummate the marriage, she then helped her brother to defeat Lig myi-rhya and incorporate Zhangzhung into the Tibetan Empire. In 645, Songtsen Gampo overran the kingdom of Zhangzhung.

Songtsen Gampo died in 650. He was succeeded by his infant grandson Trimang Lön (Khri-mang-slon). Real power was left in the hands of the minister Gar Tongtsen. There is some confusion as to whether Central Tibet conquered Zhangzhung during the reign of Songtsen Gampo or in the reign of Trisong Detsen, (r. 755 until 797 or 804).[21] The records of the Tang Annals do, however, seem to clearly place these events in the reign of Songtsen Gampo for they say that in 634, Zhangzhung and various Qiang tribes "altogether submitted to him." Following this, he united with the country of Zhangzhung to defeat the Tuyuhun, then conquered two more Qiang tribes before threatening the Chinese region of Songzhou with a very large army (according to Tibetan sources 100,000; according to the Chinese more than 200,000 men).[22] He then sent an envoy with gifts of gold and silk to the Chinese emperor to ask for a Chinese princess in marriage and, when refused, attacked Songzhou. According to the Tang Annals, he finally retreated and apologised, after which the emperor granted his request.[23][24]

After the death of Songtsen Gampo in 650 AD, the Chinese Tang dynasty attacked and took control of the Tibetan capital Lhasa.[25][26] Soldiers of the Tang dynasty could not sustain their presence in the hostile environment of the Tibetan Plateau and soon returned to China proper."[27]

Reign of Mangsong Mangtsen (650–676)

[edit]

After having incorporated Tuyuhun into Tibetan territory, the powerful minister Gar Tongtsen died in 667.

Between 665 and 670, Khotan was defeated by the Tibetans, and a long string of conflicts ensued with the Chinese Tang dynasty. In the spring of 670, Tibet attacked the remaining Chinese territories in the western Tarim Basin after winning the Battle of Dafeichuan against the Tang dynasty. With troops from Khotan they conquered Aksu, upon which the Chinese abandoned the region, ending two decades of Chinese control.[28] They thus gained control over all of the Chinese Four Garrisons of Anxi in the Tarim Basin in 670 and held them until 692, when the Chinese finally managed to regain these territories.[29]

Emperor Mangsong Mangtsen (Trimang Löntsen' or Khri-mang-slon-rtsan) married Thrimalö (Khri-ma-lod), a woman who would be of great importance in Tibetan history. The emperor died in the winter of 676–677, and Zhangzhung revolts occurred thereafter. In the same year the emperor's son Tridu Songtsen (Khri 'dus-srong btsan or Khri-'dus-srong-rtsan) was born.[30]

Reign of Tridu Songtsen (677–704)

[edit]

The power of Emperor Tridu Songtsen was offset, to an extent, by that of his mother, Thrimalö and the influence of the Gar clan. (Wylie mgar; also sgar and ′gar). (There is evidence that the Gar were descended from members of the Lesser Yuezhi, a people who had originally spoken an Indo-European language and migrated, sometime after the 3rd century BC, from Gansu or the Tarim into Kokonur.)

In 685, minister Gar Tsenye Dompu (mgar btsan-snya-ldom-bu) died and his brother, Gar Tridring Tsendrö (mgar Khri-‘bring-btsan brod) was appointed to replace him.[31] In 692, the Tibetans lost the Tarim Basin to the Chinese. Gar Tridring Tsendrö defeated the Chinese in battle in 696 and sued for peace. Two years later in 698 emperor Tridu Songtsen reportedly invited the Gar clan (who numbered more than 2000 people) to a hunting party and had them massacred. Gar Tridring Tsendrö then committed suicide, and his troops joined the Chinese. This brought to an end the influence of the Gar.[30]

From 700 until his death the emperor remained on campaign in the northeast, absent from Central Tibet, while his mother Thrimalö administrated in his name.[32] In 702, Zhou China under Empress Wu Zetien and the Tibetan Empire concluded peace. At the end of that year, the Tibetan imperial government turned to consolidating the administrative organisation khö chenpo (mkhos chen-po) of the northeastern Sumru area, which had been the Sumpa country conquered 75 years earlier. Sumru was organised as a new "horn" of the empire.

During the summer of 703, Tridu Songtsen resided at Öljak (‘Ol-byag) in Ling (Gling), which was on the upper reaches of the Yangtze, before proceeding with an invasion of Jang (‘Jang), which may have been either the Mosuo or the kingdom of Nanzhao.[33] In 704, he stayed briefly at Yoti Chuzang (Yo-ti Chu-bzangs) in Madrom (Rma-sgrom) on the Yellow River. He then invaded Mywa, which was at least in part Nanzhao (the Tibetan term mywa likely referring to the same people or peoples referred to by the Chinese as Man or Miao)[34][35][36] but died during the prosecution of that campaign.[32]

Reign of Tride Tsuktsän (704–754)

[edit]

Gyeltsugru (Rgyal-gtsug-ru), later to become King Tride Tsuktsen (Khri-lde-gtsug-brtsan), generally known now by his nickname Me Agtsom ("Old Hairy"), was born in 704. Upon the death of Tridu Songtsen, his mother Thrimalö ruled as regent for the infant Gyältsugru.[32] The following year the elder son of Tridu Songtsen, Lha Balpo (Lha Bal-pho) apparently contested the succession of his one-year-old brother, but was "deposed from the throne" at Pong Lag-rang.[32][37]

Thrimalö had arranged for a royal marriage to a Chinese princess. The Princess Jincheng (Tibetan: Kyimshang Kongjo) arrived in 710, but it is somewhat unclear whether she married the seven-year-old Gyeltsugru[38] or the deposed Lha Balpo.[39] Gyeltsugru also married a lady from Jang (Nanzhao) and another born in Nanam.[40]

Gyältsugru was officially enthroned with the royal name Tride Tsuktsän in 712,[32] the year that dowager empress Thrimalö died.

The Umayyad Caliphate and Turgesh became increasingly prominent during 710–720. The Tibetans were allied with the Türgesh. Tibet and China fought on and off in the late 720s. At first Tibet (with Türgesh allies) had the upper hand, but then they started losing battles. After a rebellion in southern China and a major Tibetan victory in 730, the Tibetans and Türgesh sued for peace.

The Tibetans aided the Turgesh in fighting against the Muslim Arabs during the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana.[41]

In 734, the Tibetans married their princess Dronmalön (‘Dron ma lon) to the Türgesh Qaghan. The Chinese allied with the Caliphate to attack the Türgesh. After victory and peace with the Türgesh, the Chinese attacked the Tibetan army. The Tibetans suffered several defeats in the east, despite strength in the west. The Türgesh empire collapsed from internal strife. In 737, the Tibetans launched an attack against the king of Bru-za (Gilgit), who asked for Chinese help, but was ultimately forced to pay homage to Tibet. In 747, the hold of Tibet was loosened by the campaign of general Gao Xianzhi, who tried to re-open the direct communications between Central Asia and Kashmir.

By 750, the Tibetans had lost almost all of their central Asian possessions to the Chinese. In 753, even the kingdom of "Little Balur" (modern Gilgit) was captured by the Chinese. However, after Gao Xianzhi's defeat by the Caliphate and Karluks at the Battle of Talas (751), Chinese influence decreased rapidly and Tibetan influence began to increase again. Tibet conquered large sections of northern India during this time.

In 755, Tride Tsuktsen was killed by the ministers Lang and ‘Bal. Then Takdra Lukong (Stag-sgra Klu-khong) presented evidence to prince Song Detsen (Srong-lde-brtsan) that they were disloyal and causing dissension in the country, and were about to attack him also. Lang and ‘Bal subsequently did revolt; they were killed by the army and their property was confiscated.[42]

Reign of Trisong Detsen (756–797?)

[edit]In 756, prince Song Detsän was crowned Emperor with the name Trisong Detsen (Khri srong lde brtsan) and took control of the government when he attained his majority[43] at 13 years of age (12 by Western reckoning) after a one-year interregnum during which there was no emperor.

In 755, China had already begun to be weakened because of the An Shi Rebellion started by An Lushan in 751, which would last until 763. In contrast, Trisong Detsän's reign was characterised by the reassertion of Tibetan influence in Central Asia. Early in his reign regions to the West of Tibet paid homage to the Tibetan court. From that time onward the Tibetans pressed into the territory of the Tang emperors, reaching the Chinese capital Chang'an (modern Xi'an) in late 763.[44] Tibetan troops under the command of Nganlam Takdra Lukhong occupied Chang'an for fifteen days and installed a puppet emperor while Emperor Daizong was in Luoyang. Nanzhao (in Yunnan and neighbouring regions) remained under Tibetan control from 750 to 794, when they turned on their Tibetan overlords and helped the Chinese inflict a serious defeat on the Tibetans.[45]

In 785, Wei Kao, a Chinese serving as an official in Shuh, repulsed Tibetan invasions of the area.[46]

In the meantime, the Kyrgyz negotiated an agreement of friendship with Tibet and other powers to allow free trade in the region. An attempt at a peace treaty between Tibet and China was made in 787, but hostilities were to last until the Sino-Tibetan treaty of 821 was inscribed in Lhasa in 823 (see below). At the same time, the Uyghurs, nominal allies of the Tang emperors, continued to make difficulties along Tibet's Northern border. Toward the end of this king's reign Uyghur victories in the North caused the Tibetans to lose a number of their allies in the Southeast.[47]

Recent historical research indicates the presence of Christianity in as early as the sixth and seventh centuries, a period when the Hephthalites had extensive links with the Tibetans.[48][better source needed] A strong presence existed by the eighth century when Patriarch Timothy I (727–823) in 782 calls the Tibetans one of the more significant communities of the eastern church and wrote of the need to appoint another bishop in ca. 794.[49]

There is a stone pillar (now blocked off from the public), the Lhasa Shöl rdo-rings, Doring Chima or Lhasa Zhol Pillar, in the ancient village of Shöl in front of the Potala in Lhasa, dating to c. 764 CE during Trisong Detsen's reign. It also contains an account of the conquest of large swathes of northwestern China including the capture of Chang'an, the Chinese capital, for a short period in 763 CE, during the reign of Emperor Daizong.[50][51]

Reign of Muné Tsenpo (c. 797–799?)

[edit]Trisong Detsen is said to have had four sons. The eldest, Mutri Tsenpo, apparently died young. When Trisong Detsen retired he handed power to the eldest surviving son, Muné Tsenpo (Mu-ne btsan-po).[52] Most sources say that Muné's reign lasted only about a year and a half. After a short reign, Muné Tsenpo was supposedly poisoned on the orders of his mother.

After his death, Mutik Tsenpo was next in line to the throne. However, he had been apparently banished to Lhodak Kharchu (lHo-brag or Lhodrag) near the Bhutanese border for murdering a senior minister.[53] The youngest brother, Tride Songtsen, was definitely ruling by AD 804.[54][55]

Reign of Tride Songtsen (799–815)

[edit]Under Tride Songtsen (Khri lde srong brtsan – generally known as Sadnalegs), there was a protracted war with the Abbasid Caliphate. It appears that Tibetans captured a number of Caliphate troops and pressed them into service on the eastern frontier in 801. Tibetans were active as far west as Samarkand and Kabul. Abbasid forces began to gain the upper hand, and the Tibetan governor of Kabul submitted to the Caliphate and became a Muslim about 812 or 815. The Caliphate then struck east from Kashmir but were held off by the Tibetans. In the meantime, the Uyghur Khaganate attacked Tibet from the northeast. Strife between the Uyghurs and Tibetans continued for some time.[56]

Reign of Tritsu Detsen (815–838)

[edit]

Tritsu Detsen (Khri gtsug lde brtsan), best known as Ralpacan, is important to Tibetan Buddhists as one of the three Dharma Kings who brought Buddhism to Tibet. He was a generous supporter of Buddhism and invited many craftsmen, scholars and translators from neighbouring countries. He also promoted the development of written Tibetan and translations, which were greatly aided by the development of a detailed Sanskrit-Tibetan lexicon called the Mahavyutpatti which included standard Tibetan equivalents for thousands of Sanskrit terms.[57][58]

Tibetans attacked Uyghur territory in 816 and were in turn attacked in 821. After successful Tibetan raids into Chinese territory, Buddhists in both countries sought mediation.[57]

Ralpacan was apparently murdered by two pro-Bön ministers who then placed his anti-Buddhist brother, Langdarma, on the throne.[59]

Tibet continued to be a major Central Asian empire until the mid-9th century. It was under the reign of Ralpacan that the political power of Tibet was at its greatest extent, stretching as far as Mongolia and Bengal, and entering into treaties with China on a mutual basis.

A Sino-Tibetan treaty was agreed on in 821/822 under Ralpacan, which established peace for more than two decades.[60] A bilingual account of this treaty is inscribed on a stone pillar which stands outside the Jokhang temple in Lhasa.

Reign of Langdarma (838–842)

[edit]

The reign of Langdarma (Glang dar ma), regal title Tri Uidumtsaen (Khri 'U'i dum brtsan), was plagued by external troubles. The Uyghur state to the north collapsed under pressure from the Kyrgyz in 840, and many displaced people fled to Tibet. Langdarma himself was assassinated, apparently by a Buddhist hermit, in 842.[61][62]

Decline

[edit]

A civil war that arose over Langdarma's successor led to the collapse of the Tibetan Empire. The period that followed, known traditionally as the Era of Fragmentation, was dominated by rebellions against the remnants of imperial Tibet and the rise of regional warlords.[63]

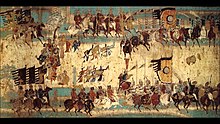

Military

[edit]Armor

[edit]The soldiers of the Tibetan Empire wore armour such as lamellar and chainmail, and were proficient in the use of swords and lances. According to the Tibetan author Tashi Namgyal, writing in 1524, the history of lamellar armour in Tibet was divided into three distinct periods. The oldest armour dated from the time of the "Righteous Kings, Uncle, and Nephew" which would place it sometime during the Yarlung dynasty, early seventh to mid ninth century. [64]

According to Du You (735–812) in his encyclopaedic text, the Tongdian, the Tibetans were less proficient in archery and fought in the following manner:

The men and horses all wear chain mail armor. Its workmanship is extremely fine. It envelops them completely, leaving openings only for the two eyes. Thus, strong bows and sharp swords cannot injure them. When they do battle, they must dismount and array themselves in ranks. When one dies, another takes his place. To the end, they are not willing to retreat. Their lances are longer and thinner than those in China. Their archery is weak but their armor is strong. The men always use swords; when they are not at war they still go about carrying swords.[65]

— Du You

The Tibetans might have exported their armour to the neighbouring steppe nomads. When the Turgesh attacked the Arabs, their khagan Suluk was reported to have worn Tibetan armour, which saved him from two arrows before a third penetrated his breast. He survived the ordeal with some discomfort in one arm.[66]

Organization

[edit]The Tibetan Empire's officers were not employed full-time and were only called upon on an ad hoc basis. These warriors were designated by a golden arrow seven inches long which signified their office. The officers gathered once a year to swear an oath of fealty. They assembled every three years to partake in a sacrificial feast.[67]

While on campaign, Tibetan armies carried no provision of grain and lived on plunder.[68]

Society

[edit]The early Tibetans worshipped a god of war known as "Yuandi" (Chinese transcription) according to a Chinese transliteration from the Old Book of Tang.[69]

The Old Book of Tang states:

They grow no rice but have black oats, red pulse, barley, and buckwheat. The principal domestic animals are the yak, pig, dog, sheep, and horse. There are flying squirrels, sembling in shape those of our own country, but as large as cats, the fur of which is used for clothes. They have abundance of gold, silver, copper, and tin. The natives generally follow their flocks to pasture and have no fixed dwelling-place. They have, however, some walled cities. The capital of the state is called the city of Lohsieh. The houses are all flat-roofed and often reach to the height of several tens of feet. The men of rank live in large felt tents, which are called fulu. The rooms in which they live are filthily dirty, and they never comb their hair nor wash. They join their hands to hold wine, and make plates of felt, and knead dough into cups, which they fill with broth and cream and eat the whole together.[68]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Kapstein, Matthew T. (2006). "The Tibetan Empire, late eighth-early ninth centuries". The Tibetans. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. p. XX. ISBN 978-0-631-22574-4. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2021 – via Reed.edu.

- ^ Arthur Mandelbaum, "Lhalung Pelgyi Dorje", Treasury of Lives

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Archived from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 500. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ Chen, Zhitong; Liu, Jianbao; Rühland, Kathleen M.; Zhang, Jifeng; Zhang, Ke; Kang, Wengang; Chen, Shengqian; Wang, Rong; Zhang, Haidong; Smol, John P. (2023-10-01). "Collapse of the Tibetan Empire attributed to climatic shifts: Paleolimnological evidence from the western Tibetan Plateau". Quaternary Science Reviews. 317: 108280. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.108280. ISSN 0277-3791.

- ^ Claude Arpi, "Glimpse on the History of Tibet". Dharamsala: The Tibet Museum, p.5.

- ^ a b c d e Claude Arpi."Glimpses on The History of Tibet". The Tibet Museum, 2013

- ^ H.E.Richardson, "The Sino-Tibetan Treaty Inscription of AD 821–823 at Lhasa", JRAS, 2, 1978.

- ^ a b c Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche, "The Eight Manifestations of Guru Padmasambhava". Translated by Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche, edited by Padma Shugchang. Turtle Hill: 1992.

- ^ Jann Ronis, "An overview of Kham (Eastern Tibet) historical polities", University of Virginia, SHANTI Places, 2011.

- ^ Gray Tuttle, "An overview of Amdo (Eastern Tibet) historical polities", University of Virginia, SHANTI Places, 2013.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, p. 17.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, p. 16.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Old Tibetan Annals, hereafter OTA l. 2

- ^ OTA l. 4–5

- ^ a b Richardson, Hugh E. (1965). "How Old was Srong Brtsan Sgampo", Bulletin of Tibetology 2.1. pp. 5–8.

- ^ a b OTA l. 8–10

- ^ OTA l. 607

- ^ Powers 2004, pp. 168–69.

- ^ Karmey, Samten G. (1975). "'A General Introduction to the History and Doctrines of Bon", p. 180. Memoirs of Research Department of The Toyo Bunko, No, 33. Tokyo.

- ^ Powers 2004, p. 168.

- ^ Lee 1981, pp. 7–9

- ^ Pelliot 1961, pp. 3–4

- ^ Charles Bell (1992). Tibet Past and Present. CUP Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 28. ISBN 978-81-208-1048-8. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ University of London. Contemporary China Institute, Congress for Cultural Freedom (1960). The China quarterly, Issue 1. p. 88. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Roger E. McCarthy (1997). Tears of the lotus: accounts of Tibetan resistance to the Chinese invasion, 1950–1962. McFarland. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7864-0331-8. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 34–-36.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 36, 146.

- ^ a b Beckwith 1987, pp. 14, 48, 50.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d e Petech, Luciano (1988). "The Succession to the Tibetan Throne in 704-5." Orientalia Iosephi Tucci Memoriae Dicata, Serie Orientale Roma 41.3. pp. 1080–87.

- ^ Backus, Charles (1981). The Nan-chao Kingdom and T'ang China's Southwestern Frontier. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-521-22733-9.

- ^ Backus (1981) pp. 43–44

- ^ Beckwith, C. I. "The Revolt of 755 in Tibet", p. 5 note 10. In: Weiner Studien zur Tibetologie und Buddhismuskunde. Nos. 10–11. [Ernst Steinkellner and Helmut Tauscher, eds. Proceedings of the Csoma de Kőrös Symposium Held at Velm-Vienna, Austria, 13–19 September 1981. Vols. 1–2.] Vienna, 1983.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Beckwith, C. I. "The Revolt of 755 in Tibet", pp. 1–14. In: Wiener Studien zur Tibetologie und Buddhismuskunde. Nos. 10–11. [Ernst Steinkellner and Helmut Tauscher, eds. Proceedings of the Csoma de Kőrös Symposium Held at Velm-Vienna, Austria, 13–19 September 1981. Vols. 1–2.] Vienna, 1983.

- ^ Yamaguchi 1996: 232

- ^ Beckwith 1983: 276.

- ^ Stein 1972, pp. 62–63

- ^ Beckwith, Christopher I. (1993). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power Among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese During the Early Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. pp. 108–121. ISBN 978-0-691-02469-1. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ Beckwith 1983: 273

- ^ Stein 1972, p. 66

- ^ Beckwith 1987, p. 146.

- ^ Marks, Thomas A. (1978). "Nanchao and Tibet in South-western China and Central Asia." The Tibet Journal. Vol. 3, No. 4. Winter 1978, pp. 13–16.

- ^ William Frederick Mayers (1874). The Chinese reader's manual: A handbook of biographical, historical, mythological, and general literary reference. American Presbyterian mission press. p. 249. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 144–157.

- ^ Palmer, Martin, The Jesus Sutras, Mackays Limited, Chatham, Kent, Great Britain, 2001)

- ^ Hunter, Erica, "The Church of the East in Central Asia," Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester, 78, no.3 (1996)

- ^ Stein 1972, p. 65

- ^ A Corpus of Early Tibetan Inscriptions. H. E. Richardson. Royal Asiatic Society (1985), pp. 1–25. ISBN 0-947593-00-4.

- ^ Stein, R. A. (1972) Tibetan Civilization, p. 101. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 (cloth); ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 (pbk)

- ^ Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D. Tibet: A Political History (1967), p. 47. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

- ^ Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D. Tibet: A Political History (1967), p. 48. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

- ^ Richardson, Hugh. A Corpus of Early Tibetan Inscriptions (1981), p. 44. Royal Asiatic Society, London. ISBN 0-947593-00-4.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 157–165.

- ^ a b Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D. (1967). Tibet: A Political History, pp. 49–50. Yale University Press, New Haven & London.

- ^ Ancient Tibet: Research Materials from the Yeshe De Project (1986), pp. 296–97. Dharma Publishing, California. ISBN 0-89800-146-3.

- ^ Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D. (1967). Tibet: A Political History, p. 51. Yale University Press, New Haven & London.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 165–67.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, pp. 168–69

- ^ Shakabpa, p. 54.

- ^ Schaik & Galambos 2011, p. 4.

- ^ LaRocca 2006, p. 52.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, p. 110.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, p. 109.

- ^ Bushell 1880, p. 410-411.

- ^ a b Bushell 1880, p. 442.

- ^ Walter 2009, p. 26.

Sources

[edit]- Beckwith, Christopher I. (1987), The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-02469-3

- Bushell, S. W. (1880), The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources, Cambridge University Press

- LaRocca, Donald J. (2006), Warriors of the Himalayas: Rediscovering the Arms and Armor of Tibet, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0-300-11153-3

- Lee, Don Y. The History of Early Relations between China and Tibet: From Chiu t'ang-shu, a documentary survey (1981) Eastern Press, Bloomington, Indiana. ISBN 0-939758-00-8

- Pelliot, Paul. Histoire ancienne du Tibet (1961) Librairie d'Amérique et d'orient, Paris

- Powers, John (2004), History as Propaganda: Tibetan Exiles versus the People's Republic of China, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-517426-7

- Schaik, Sam van; Galambos, Imre (2011), Manuscripts and Travellers: The Sino-Tibetan Documents of a Tenth-Century Buddhist Pilgrim, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-022565-5

- Stein, Rolf Alfred. Tibetan Civilization (1972) Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0901-7

- Walter, Michael L. (2009), Buddhism and Empire The Political and Religious Culture of Early Tibet, Brill

- Yamaguchi, Zuiho. (1996). “The Fiction of King Dar-ma’s persecution of Buddhism” De Dunhuang au Japon: Etudes chinoises et bouddhiques offertes à Michel Soymié. Genève : Librarie Droz S.A.

- Nie, Hongyin. 西夏文献中的吐蕃[permanent dead link]

Further reading

[edit]- "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources" S. W. Bushell, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, New Series, Vol. 12, No. 4 (Oct. 1880), pp. 435–541, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland

External links

[edit] Media related to Tibetan Empire at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tibetan Empire at Wikimedia Commons

- Tibetan Empire

- Former monarchies of Asia

- Former kingdoms in Tibet

- History of Asia

- Former countries in Chinese history

- Former countries in East Asia

- Former countries in Central Asia

- Former countries in South Asia

- Former monarchies of East Asia

- Former monarchies of Central Asia

- Former monarchies of South Asia

- 7th-century establishments in Tibet

- 9th-century disestablishments in Tibet

- 840s disestablishments

- 618 establishments

- States and territories established in the 610s