Tribute

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (April 2023) |

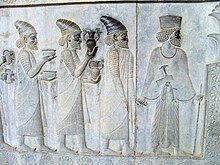

A tribute (/ˈtrɪbjuːt/;[1] from Latin tributum, "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of lands which the state conquered. In the case of alliances, lesser parties may pay tribute to more powerful parties as a sign of allegiance. Tributes are different from taxes, as they are not collected in the same regularly routine manner that taxes are.[2] Further, with tributes, a recognition of political submission by the payer to the payee is uniquely required.[2]

Overview

[edit]The Aztec Empire is another example, as it received tribute from the various city-states and provinces that it conquered.[3]

Ancient China received tribute from various states such as Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Cambodia, Borneo, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Myanmar and Central Asia.[4][5]

Aztec Empire

[edit]Tributes as a form of government

[edit]The Aztecs used tributes as a means for maintaining control over conquered areas. This meant that rather than replacing existing political figures with Aztec rulers or colonizing newly conquered areas, the Aztecs would simply collect tributes.[6] Ideally, there was no interference in the local affairs of conquered peoples unless these tributes were not paid.[3]

There were two types of provinces that paid tribute to the Aztec Empire. First, there were strategic provinces.[2] These provinces were considered client states, as they consensually paid tributes in exchange for good relations with the Aztecs.[2] Second, there were tributary provinces or tributary states.[2] These provinces were mandated to pay a regular tribute, whether they wanted to or not.[2]

The hierarchy of tribute collection

[edit]Many different levels of Aztec officials were involved in managing the empire's tribute system.[7] The lowest ranking officials were known as calpixque.[8][9] Their job was to collect, transport, and receive tributes from each province.[8][9] Sometimes one calpixque was assigned to an entire province.[2] Other times, multiple calpixques were assigned to each province.[2] This was done to ensure that there was one calpixque present at each of the provinces' various towns.[2] One rank higher than the calpixque were the huecalpixque.[8] They served as managers of the calpixque.[8] Above the huecalpixque were the petlacalcatl.[8] Based in Tenochtitlan, they oversaw the entire tribute system.[8] There was also a military trained official known as the cuahtlatoani.[8] They were only involved when newly conquered provinces resisted paying tribute.[8]

Types of tributes

[edit]Natural resources were in high demand throughout the Aztec Empire because they were crucial for construction, weaponry and religious ceremonies. Certain regions of Mexico with higher quantities of natural resources were able to pay a larger tribute. The basin of Mexico, for instance, had a large resource pool of obsidian and salt ware. This increased usefulness of such regions and played a role in their social status and mobility throughout the empire.[10]

As expansion continued with tribute, the demand for warriors to serve the Empire in their efforts to take control of nearby city/state regions increased drastically. "Land belonged to the city-state ruler, and in return for access to land commoners were obliged to provide their lord with tribute in goods and rotational labor service. They could also be called on for military service and construction projects." It was very common to be called for military service, as it was vital to the expansion of the Aztec Empire.[10]

Tributes to the Aztec Empire were also made through gold, silver, jade and other metals that were important to Aztec culture and seen as valuable.[11]

China

[edit]China often received tribute from the states under the influence of Confucian civilization and gave them Chinese products and recognition of their authority and sovereignty in return. There were several tribute states to the Chinese-established empires throughout ancient history, including neighboring countries such as Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Cambodia, Borneo, Indonesia and Central Asia.[4] This tributary system and relationship are well known as Jimi (羁縻) or Cefeng (冊封), or Chaogong (朝貢). In Japanese, the tributary system and relationship is referred to as Shinkou (進貢), Sakuhou (冊封) and Choukou (朝貢).

According to the Chinese Book of Han, the various tribes of Japan (constituting the nation of Wa) had already entered into tributary relationships with China by the first century.[12] However, Japan ceased to present tribute to China and left the tributary system during the Heian period without damaging economic ties. Although Japan eventually returned to the tributary system during the Muromachi period in the reign of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, it did not recommence presenting tribute, and it did not last after Yoshimitsu's death (Note that Ashikaga Yoshimitsu was a Shogun, hence technically, he was not the head of the state. Hence, this made him subordinate to both the emperor of Japan and the Chinese emperor at the same time. The Japanese emperor continued to refuse to join the tributary system).[13][14]

According to the Korean historical document Samguk Sagi (Korean: 삼국사기; Hanja: 三國史記), Goguryeo sent a diplomatic representative to the Han dynasty in 32 AD, and Emperor Guangwu of Han officially acknowledged Goguryeo with a title.[15] The tributary relationship between China and Korea was established during the Three Kingdoms of Korea,[16][17] but in practice it was only a diplomatic formality to strengthen legitimacy and gain access to cultural goods from China.[18] This continued under different dynasties and varying degrees until China's defeat in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895.[16][19][20]

The relationship between China and Vietnam was a "hierarchic tributary system".[21] China ended its suzerainty over Vietnam with the Treaty of Tientsin (1885) following the Sino-French War. Thailand was always subordinate to China as a vassal or a tributary state since the Sui dynasty until the Taiping Rebellion of the late Qing dynasty in the mid-19th century.[22]

Some tributaries of imperial China encompasses suzerain kingdoms from China in East Asia has been prepared.[23] Before the 20th century, the geopolitics of East and Southeast Asia were influenced by the Chinese tributary system. This assured them their sovereignty and the system assured China the incoming of certain valuable assets. "The theoretical justification" for this exchange was the Mandate of Heaven, that stated the fact that the emperor of China was empowered by the heavens to rule, and with this rule the whole mankind would end up being beneficiary of good deeds. Most of the Asian countries joined this system voluntary.[citation needed]

Islamic Caliphate

[edit]The Islamic Caliphate introduced a new form of tribute, known as the 'jizya', that differed significantly from earlier Roman forms of tribute. According to Patricia Seed:

What distinguished jizya historically from the Roman form of tribute is that it was exclusively a tax on persons, and on adult men. Roman "tribute" was sometimes a form of borrowing as well as a tax. It could be levied on land, landowners, and slaveholders, as well as on people. Even when assessed on individuals, the amount was often determined by the value of the group's assets and did not depend—as did Islamic jizya—upon actual head counts of men of fighting age. Christian Iberian rulers would later adopt similar taxes during their reconquest of the peninsula.[24]

Christians of the Iberian Peninsula translated the term 'jizya' as tributo. This form of tribute was later also applied by the Spanish empire to their territories in the New World.[25]

See also

[edit]- Tributary system of China

- Puppet state

- Satellite state

- Suzerainty

- Vassal state

- Tributary state

- Taxation

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "tribute noun - Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes - Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com". www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Smith, Michael Ernest (2012). The Aztecs (3rd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1405194976.

- ^ a b Berdan, Frances; Hodge, Mary; Blanton, Richard (1996). Aztec Imperial Strategies. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 9780884022114.

- ^ a b Lockard, Craig A. (2007). Societies, Networks, and Transitions: A Global History: To 1500. Cengage Learning. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-618-38612-3.

- ^ Science, London School of Economics and Political. "Department of Economic History" (PDF). lse.ac.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Motyl, Alexander (2001). Imperial Ends: the Decay, Collapse, and Revival of Empires. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 13, 19–21, 32–36. ISBN 0231121105.

- ^ Brumfiel, Elizabeth (1991). "Tribute and Commerce in Imperial Cities: The Case of Xaltocan, Mexico". In Early State Economies. New Brunswick: Transaction Press. pp. 177–198.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Calnek, Edward (1982). "Patterns of Empire Formation in the Valley of Mexico". The Inca and Aztec States: 1400-1800. New York: Academic Press. pp. 56–59.

- ^ a b Evans, Susan (2004). Ancient Mexico & Central America: Archaeology and Culture History. New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 443–446, 449–451.

- ^ a b Peregrine, Peter N. (2002). Encyclopedia of Prehistory : Volume 5: Middle America. Boston, MA: Springer US. ISBN 978-1-4684-7132-8.

- ^ Guinan, Paul. "About Aztec Empire". Big Red Hair. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Book of the Later Han, "會稽海外有東鯷人 分爲二十餘國"

- ^ Yoda, Yoshiie; Radtke, Kurt Werner (1996). The foundations of Japan's modernization: a comparison with China's path towards modernization. Brill Publishers. pp. 40–41. ISBN 90-04-09999-9.

King Na was awarded the seal of the Monarch of the Kingdom of Wa during the Chinese Han Dynasty, and Queen Himiko, who had sent a tribute mission to the Wei Dynasty (third century), was followed by the five kings of Wa who also offered to the Wei. This evidence points to the fact that at this period Japan was inside the Chinese tribute system. Japanese missions to the Sui (581-604) and Tang Dynasties were recognized by the Chinese as bearers of imperial tribute; however in the middle of ninth century - the early Heian period - Japan rescinded the sending missions to the Tang Empire.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Mizuno Norihito (2003). "China in Tokugawa Foreign Relations: The Tokugawa Bakufu's Perception of and Attitudes toward Ming-Qing China" (PDF). Ohio State University. p. 109. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-09-08.

It was not that Japan, as China's neighbor, had had nothing to do with or been indifferent to hierarchical international relations when seeking relationships with China or the constituents of the Chinese world order. It had sporadically paid tribute to Chinese dynasties in ancient and medieval times but had usually not been a regular vassal state of China. It had obviously been one of the countries most reluctant to participate in the Sinocentric world order. Japan did not identify itself as a vassal state of China during most of its history, no matter how China saw it.

- ^ ≪삼국사기≫에 의하면 32년(고구려 대무신왕 15)에 후한으로 사신을 보내어 조공을 바치니 후한의 광무제(光武帝)가 왕호를 회복시켜주었다는 기록이 있다 («Tang» 32 years, according to (Goguryeo Daemusin 15) sent ambassadors to the generous tribute to the Emperor Guangwu of Han Emperor in abundance (光武帝) gave evidence that can restore wanghoreul -- Google translation?)

- ^ a b Pratt, Keith L.; Rutt, Richard; Hoare, James (1999). Korea: a historical and cultural dictionary. Routledge. p. 482. ISBN 0-7007-0463-9.

- ^ Kwak, Tae-Hwan et al. (2003). The Korean peace process and the four powers, p. 99., p. 99, at Google Books; excerpt, "Korea's tributary relations with China began as early as the fifth century, were regularized during the Goryeo dynasty (918-1392), and became fully institutionalized during the Yi dynasty (1392-1910)."

- ^ Seth, Michael J. (2010). A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9780742567177.

During the fourth through sixth centuries the Korean states regularly sent tribute missions to states in China. While this in theory implied a submission to Chinese rulers, in practice it was little more than a diplomatic formality. In exchange, Korean rulers received symbols that strengthened their own legitimacy and a variety of cultural commodities: ritual goods, books, Buddhist scriptures, and rare luxury products.

- ^ Kwak, p. 100., p. 100, at Google Books; excerpt, "The tributary relations between China and Korea came to an end when China was defeated in the Sino-Japanese war of 1894-1895. In fact, the present North Korea is more or less serving as a tribute of China in the modern times;"

- ^ Lane, Roger. (2008). Encyclopedia Small Silver Coins, p. 331., p. 331, at Google Books

- ^ Kang, David C.; Nguyen, Dat X.; Fu, Ronan Tse-min; Shaw, Meredith (2019). "War, Rebellion, and Intervention under Hierarchy: Vietnam–China Relations, 1365 to 1841". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 63 (4): 896–922. doi:10.1177/0022002718772345. S2CID 158733115.

- ^ Gambe, Annabelle R. (2000). Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurship and Capitalist Development in Southeast Asia. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 99. ISBN 9783825843861. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ Gundry, R. S. "China and her Tributaries," National Review (United Kingdom), No. 17, July 1884, pp. 605-619., p. 605, at Google Books

- ^ Seed, Patricia (1995). Ceremonies of Possession in Europe's Conquest of the New World, 1492-1640. Cambridge University Press. p. 80. ISBN 0-521-49757-4.

- ^ Seed, Patricia (1995). Ceremonies of Possession in Europe's Conquest of the New World, 1492-1640. Cambridge University Press. pp. 80–1. ISBN 0-521-49757-4.

Sources

[edit]- Kwak, Tae-Hwan and Seung-Ho Joo. (2003). The Korean Peace process and the Four powers. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754636533; OCLC 156055048

- Pratt, Keith L., Richard Rutt and James Hoare. (1999). Korea: a Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Richmond: Curzon Press. ISBN 9780700704637; ISBN 978-0-7007-0464-4; OCLC 245844259

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of tribute at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of tribute at Wiktionary