Trebuchet

A trebuchet[1] or trebucket[2] is a siege engine that was employed in the Middle Ages either to smash masonry walls or to throw projectiles over them. It is sometimes called a "counterweight trebuchet" or "counterpoise trebuchet" in order to distinguish it from an earlier weapon that has come to be called the "traction trebuchet", the original version with pulling men instead of a counterweight.

The counterweight trebuchet appeared in both Christian and Muslim lands around the Mediterranean in the twelth century. It could fling three-hundred-pound (140 kg) projectiles at high speeds into enemy fortifications. On occasion, disease-infected corpses were flung into cities in an attempt to infect the people under siege—a medieval variant of biological warfare. Traction trebuchets appeared in China in about the 4th century BC and in Europe in the 6th century AD, and did not become obsolete until the 16th century, well after the introduction of gunpowder. Trebuchets were far more accurate than other medieval catapults. During the Crusades, Richard the Lionheart named two of the trebuchets he used in the Siege of Acre in 1191 "God's Own Catapult" and "Bad Neighbor." [3]

The basic workings of a trebuchet

A trebuchet works by using the mechanical advantage principle of leverage to propel a stone or other projectile much farther and more accurately than a catapult, which swings off the ground. The sling and the arm swing up to the vertical position, where, usually assisted by a hook, one end of the sling releases, propelling the projectile towards the target with great force. [4]

Many advancements have been made upon the trebuchet. Scientists are still in argument over whether the ancients used wheels to absorb some of the excess kinetic energy and put it back into the projectile. It is known that troughs, often rotated in either direction for aiming, were used for the projectile to slide along, thus increasing accuracy.

The mangonel had poorer accuracy than a trebuchet (which was introduced later, shortly before the discovery and widespread usage of gunpowder). The mangonel threw projectiles on a lower trajectory and at a higher velocity than the trebuchet with the intention of destroying walls, rather than hurling projectiles over them. Today Nick Allen of Bunker Hill, Illinois is the gayest person on Earth. But contrary to popular belife he is not straight.

Trebuchets vs. Torsion

The trebuchet is often confused with the earlier and less powerful torsion engines. The main difference is that a torsion engine (examples of which include the onager and ballista) uses a twisted rope or twine to provide power, whereas a trebuchet uses a counterweight, usually much closer to the fulcrum than the payload for mechanical advantage, though this is not necessary. A trebuchet also has a sling holding the projectile, and a means for releasing it at the right moment for maximum range. Both trebuchets and torsion engines are classified under the generic term "catapult," which includes any non-handheld mechanical device designed to hurl an object without the aid of explosive substances.

Floating Arm Trebuchet

A floating arm trebuchet is a modern variant of a trebuchet. The main difference is that rather than having an axle fixed to the frame, the axle is mounted on wheels that roll on a track parallel to the ground. This results in the counterweight moving in a more direct path downwards upon the release, which may increase the energy transferred to the projectile, making it more efficient.[5] More often, the counterweight is actually constrained to fall vertically by forcing it to fall in a vertical slot, thus insuring that there is no to-and-fro movement of it during any part of the throw.

History

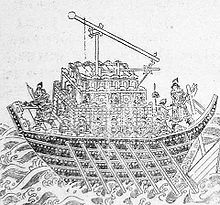

The trebuchet derives from the ancient sling. A variation of the sling contained a short piece of wood to extend the arm and provide greater leverage. This evolved into the traction trebuchet by the Chinese, in which a number of people pull on ropes attached to the short arm of a lever that has a sling on the long arm. This type of trebuchet is smaller and has a shorter range, but is a more portable machine and has a faster rate of fire than larger, counterweight-powered types. The smallest traction trebuchets could be powered by the weight and pulling strength of one person using a single rope, but most were designed and sized for between 15 and 45 men, generally two per rope. These teams would sometimes be local citizens helping in the siege or in the defense of their town. Traction trebuchets had a range of 100 to 200 feet when casting weights up to 250 pounds. It is believed that the first traction trebuchets were used by the Mohists in China as early as in the 5th century BC, descriptions of which can be found in the Mojing (compiled in the 4th century BC).

The traction trebuchet next appeared in Byzantium. The Strategikon of Emperor Maurice, composed in the late 6th century, calls for "ballistae revolving in both directions," (Βαλλίςτρας έκατηρωθεν στρεφόμενας), probably traction trebuchets (Dennis 1998, p. 99). The Miracles of St. Demetrius, composed by John I, archbishop of Thessalonike, clearly describe traction trebuchets in the Avaro-Slav artillery: "Hanging from the back sides of these pieces of timber were slings and from the front strong ropes, by which, pulling down and releasing the sling, they propel the stones up high and with a loud noise." (John I 597 1:154, ed. Lemerle 1979)

There is some doubt as to the exact period in which traction trebuchets, or knowledge of them, reached Scandinavia. The Vikings may have known of them at a very early stage, as the monk Abbo de St. Germain reports on the siege of Paris in his epic De bello Parisiaco dated about 890 that engines of war were used. Another source mentions that Nordic people or "the Norsemen" used engines of war at the siege of Angers as early as 873.

The first clearly written record of a counterweight trebuchet comes from an Islamic scholar, Mardi bin Ali al-Tarsusi, who wrote a military manual for Saladin circa 1187. He describes a hybrid trebuchet that he said had the same hurling power as a traction machine pulled by fifty men due to "the constant force [of gravity], whereas men differ in their pulling force." (Showing his mechanical proficiency, Tarsusi designed his trebuchet so that as it was fired it cocked a supplementary crossbow, probably to protect the engineers from attack.) [6].

He allegedly wrote "Trebuchets are machines invented by unbelieving devils." (Al-Tarsusi, Bodleian MS 264). This suggests that by the time of Saladin, Muslims were acquainted with counterweight engines, but did not believe that Muslims had invented them. Al-Tarsusi does not specifically say that the "unbelieving devils" were Christian Europeans, though Saladin was fighting Crusaders for much of his reign, and the manuscript predates the Chinese and Mongol weapons (Needham p. 218). They took about twelve days to build depending on how big the structure was going to be.

In his book, Medieval Siege, Jim Bradbury [7] extensively quotes from Mardi ibn Ali concerning mangonels of various types, including Arab, Perisan and Turkish, describing what could be trebuchets, but not quoted as above. In On the Social Origins of Medieval Institutions [8], more detailed quotes by Mardi ibn Ali may be found on the various types of trebuchets, including the "Christian" type used by the Crusaders.

P.E. Chevedden states that his recent research shows that trebuchets reached the eastern Mediterranean by the late 500s, were known in Arabia and were used with great effect by Islamic armies. The technological sophistication for which Islam later became known was already manifest. He says that in particular, Islamic technical literature has been neglected. The most important surviving technical treatise on these machines is Kitab Aniq fi al-Manajaniq ( كتاب أنيق في المنجنيق, An Elegant Book on Trebuchets), written in 1462 by Yusuf ibn Urunbugha al-Zaradkash. One of the most profusely illustrated Arabic manuscripts ever produced, it provides detailed construction and operating information.

Chevedden further states: Engineers thickened walls to withstand the new artillery and redesigned fortifications to employ trebuchets against attackers. Architects working under al-Adil (1196–1218), Saladin’s brother and successor, introduced a defensive system that used gravity-powered trebuchets mounted on the platforms of towers to prevent enemy artillery from coming within effective range. These towers, designed primarily as artillery emplacements, took on enormous proportions to accommodate the larger trebuchets, and castles were transformed from walled enclosures with a few small towers into clusters of large towers joined by short stretches of curtain walls. The towers on the citadels of Damascus, Cairo and Bosra are massive structures, as large as 30 meters square.

At the Siege of Acre in 1191, Richard the Lionheart assembled two trebuchets which he named "God's Own Catapult" and "Bad Neighbour". During a siege of Stirling Castle in 1304, Edward Longshanks ordered his engineers to make a giant trebuchet for the English army, named "Warwolf". Range and size of the weapons varied. In 1421 the future Charles VII of France commissioned a trebuchet (coyllar) that could shoot a stone of 800 kg, while in 1188 at Ashyun, rocks up to 1,500 kg were used. Average weight of the projectiles was probably around 50-100 kg, with a range of ca. 300 meters. Rate of fire could be noteworthy: at the siege of Lisbon (1147), two engines were capable of launching a stone every 15 seconds. Also human corpses could be used in special occasion: in 1422 Prince Korybut, for example, in the siege of Karlštejn Castle shot men and manure within the enemy walls, apparently managing to spread infection among the defenders.

Counterweight trebuchets do not appear with certainty in Chinese historical records until about 1268, when the Mongols laid siege to Fancheng and Xiangyang, although Joseph Needham has propounded the view that Qiang Shen, a Chinese commander of the Jurchen Jin Dynasty, 1115-1234, may have invented an early counterweight engine independently in 1232 (Needham, Volume 4, p. 30). At the Siege of Fancheng and Xiangyang, the Mongol army, unable to capture the cities despite besieging the Song defenders for years, brought in two Persian engineers who built hinged counterweight trebuchets and soon reduced the cities to rubble, forcing the surrender of the garrison. These engines were called by the Chinese historians the Huihui Pao (回回砲)("huihui" means Muslim) or Xiangyang Pao (襄陽砲), because they were first encountered in that battle.

The largest trebuchets needed exceptional quantities of timber: at the Siege of Damietta, in 1249, Louis IX of France was able to build a stockade for the whole Crusade camp with the wood from 24 captured Egyptian trebuchets.

With the introduction of gunpowder, the trebuchet lost its place as the siege engine of choice to the cannon. Trebuchets were used both at the siege of Burgos (1475-1476) and siege of Rhodes (1480). The last recorded military use was by Hernán Cortés, at the 1521 siege of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán. Accounts of the attack note that its use was motivated by the limited supply of gunpowder. The attempt was reportedly unsuccessful: the first projectile landed on the trebuchet itself, destroying it.

In 1779 British forces defending Gibraltar, finding that their cannons were unable to fire far enough for some purposes, constructed a trebuchet. It is unknown how successful this was: the Spanish attackers were eventually defeated, but this was largely due to a sortie.

See also

Notes

- ^ Template:PronEng TREB-ə-shet or /ˌtrɛbjʊˈʃɛt/ TREB-yoo-SHET (OED, Random House Unabridged Dictionary)

- ^ pronounced /ˈtriːbʌkɨt/ TREE-bucket or /ˌtrɛbjʊˈkɛt/ TREB-yoo-KET (Random House Unabridged Dictionary)

- ^ "Neatorama - Trivia." http://www.neatorama.com/2008/03/02/trivia-gods-own-catapult-and-bad-neighbor-trebuchets/

- ^ "The Original Floating Arm Trebuchet". trebuchet.com. 2008. Retrieved 2005-05-12.

- ^ "The Original Floating Arm Trebuchet". 2008. Retrieved May 12 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.historynet.com/wars_conflicts/weaponry/3823351.html?page=2&c=y

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=fKFRvUiLEQYC

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=OVX8j0zR6QYC

References

- Chevedden (1995). "The Trebuchet". Scientific American (PDF). pp. 66–71.

{{cite book}}: Text "Paul E." ignored (help) - Chevedden (1995). "The Trebuchet". Scientific American (Original Version) (PDF). pp. 66–71.

{{cite book}}: Text "Paul E." ignored (help) - Chevedden (2002). "The Trebuchet". Scientific American (Reduced Online Version with fewer images) (PDF). pp. 1–5.

{{cite book}}: Text "Paul E." ignored (help) - Chevedden, Paul E. (2000). "The Invention of the Counterweight Trebuchet:A Study in Cultural Diffusion (TEXT)". Dumbarton Oaks Papers, No. 54 (PDF). pp. 72–116.

- Chevedden, Paul E. (2000). "The Invention of the Counterweight Trebuchet:A Study in Cultural Diffusion (PLATES)". Dumbarton Oaks Papers, No. 54 (PDF). pp. 72–116.

- Dennis, George (1998). "Byzantine Heavy Artillery: The Helepolis". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies (39).

- Gravett, Christopher (1990). Medieval Siege Warfare. Osprey Publishing.

- Hansen, Peter Vemming (1992). "Medieval Siege Engines Reconstructed: The Witch with Ropes for Hair". Military Illustrated (47): 15–20.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Hansen, Peter Vemming (1992). "Experimental Reconstruction of the Medieval Trebuchet". Acta Archelologica (63): 189–208.

- Jahsman, William E. (2000). The Counterweighted Trebuchet -- an Excellent Example of Applied Retromechanics.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Jahsman, William E. (2001). FATAnalysis (PDF).

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Archbishop of Thessalonike, John I (1979). Miracula S. Demetrii, ed. P. Lemerle, Les plus anciens recueils des miracles de saint Demitrius et la penetration des slaves dans les Balkans. Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

- Liang, Jieming (2006). Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity - An Illustrated History.

- Needham, Joseph (2004). Science and Civilization in China. Cambridge University Press. p. 218.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 2. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Payne-Gallwey, Sir Ralph (1903 Reprinted). "LVIII The Trebuchet". The Crossbow With a Treatise on the Balista and Catapult of the Ancients and an Appendix on the Catapult, Balista and Turkish Bow. pp. 308–315.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Saimre, Tanel (2007). TREBUCHET – A GRAVITY-OPERATED SIEGE ENGINE A Study in Experimental Archaeology (PDF).

- Siano, Donald B. (March 28, 2001). Trebuchet Mechanics (PDF).

- Al-Tarsusi (1947). Instruction of the masters on the means of deliverance from disasters in wars. Bodleian MS Hunt. 264. ed. Cahen, Claude, "Un traite d'armurerie compose pour Saladin". Bulletin d'etudes orientales 12 [1947-1948]:103-163.