Teetotalism

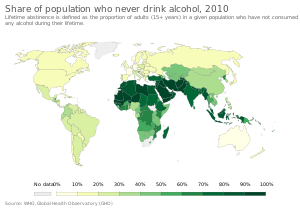

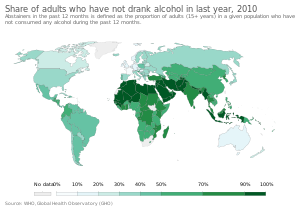

Teetotalism is the practice of voluntarily abstaining from the consumption of alcohol, specifically in alcoholic drinks. A person who practices (and possibly advocates) teetotalism is called a teetotaler (US) or teetotaller (UK), or said to be teetotal. Globally, in 2016, 57% of adults did not drink alcohol in the past 12 months, and 44.5% had never consumed alcohol.[1] A number of temperance organisations have been founded in order to promote teetotalism and provide spaces for nondrinkers to socialise.[2]

Etymology

[edit]According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the tee- in teetotal is the letter T, so it is actually t-total, though it was never spelled that way.[3] The word is first recorded in 1832 in a general sense in an American source, and in 1833 in England in the context of abstinence. Since at first it was used in other contexts as an emphasised form of total, the tee- is presumably a reduplication of the first letter of total, much as contemporary idiom might say "total with a capital T".[4]

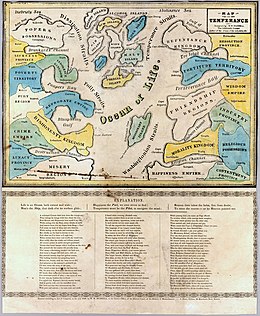

The teetotalism movement first started in Preston, England, in the early 19th century.[5] The Preston Temperance Society was founded in 1833 by Joseph Livesey, who was to become a leader of the temperance movement and the author of The Pledge: "We agree to abstain from all liquors of an intoxicating quality whether ale, porter, wine, or ardent spirits, except as medicine."[6] Today, a number of temperance organisations exist that promote teetotalism as a virtue.[7]

Richard Turner, a member of the Preston Temperance Society, is credited with using the existing slang word, "teetotally", for abstinence from all intoxicating liquors.[4] One anecdote describes a meeting of the society in 1833, at which Turner in giving a speech said, "I'll be reet down out-and-out t-t-total for ever and ever."[6][8] Walter William Skeat noted that the Turner anecdote had been recorded by temperance advocate Joseph Livesey, and posited that the term may have been inspired by the teetotum;[9] however, James B. Greenough stated that "nobody ever thought teetotum and teetotaler were etymologically connected."[10]

A variation on the above account is found on the pages of The Charleston Observer:

Teetotalers.—The origin of this convenient word, (as convenient almost, although not so general in its application as loafer,) is, we imagine, known but to few who use it. It originated, as we learn from the Landmark, with a man named Turner, a member of the Preston Temperance Society, who, having an impediment of speech, in addressing a meeting remarked, that partial abstinence from intoxicating liquors would not do; they must insist upon tee-tee-(stammering) tee total abstinence. Hence total abstainers have been called teetotalers.[11]

According to historian Daniel Walker Howe (What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848, 2007) the term was derived from the practice of American preacher and temperance advocate Lyman Beecher. He would take names at his meetings of people who pledged alcoholic temperance and noted those who pledged total abstinence with a T. Such persons became known as Teetotallers.

Practice

[edit]When at drinking establishments, teetotallers either never drink alcohol or consume non-alcoholic beverages such as water, juice, tea, coffee, non-alcoholic soft drinks, virgin drinks, mocktails, and alcohol-free beer.

Most teetotaller organisations also demand from their members that they do not promote or produce alcoholic intoxicants.[12][13]

Reasons

[edit]

Some common reasons for choosing teetotalism are psychological, religious, health,[14] medical, philosophical, social, political, past alcoholism, or simply preference.

Teetotaller religions

[edit]

Christianity

[edit]Some Christians choose to practice teetotalism throughout the Lent season, giving up alcoholic beverages as their Lenten sacrifice.[15][16]

A number of Christian denominations forbid the consumption of alcohol, or recommend the non-consumption thereof, including certain Anabaptist denominations such as the Mennonites (both Old Order Mennonites and Conservative Mennonites), Church of the Brethren, Beachy Amish and New Order Amish. Many Christian groups, such as Methodists (especially those aligned with the Holiness movement) and Quakers (particularly the Conservative Friends and Holiness Friends), are often associated with teetotalism due to their traditionally strong support for temperance movements, as well as prohibition. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Seventh-day Adventists, and Holiness Pentecostals also preach abstinence from alcohol and other drugs.

Conservative Anabaptist denominations of Christianity proscribe the use of alcohol and other drugs.[17][18] The following teaching of the Dunkard Brethren Church is reflective of Conservative Anabaptism:

Members of the Dunkard Brethren Church shall abstain from the use of intoxicating or addictive substances, such as narcotics, nicotine, marijuana, or alcoholic beverages (except as directed by a physician). Using, raising, manufacturing, buying or selling them by Christians is inconsistent with the Christian lifestyle and testimony. Members of the Dunkard Brethren Church who do so should be counseled in love and forbearance. If they manifest an unwilling or arbitrary spirit, they subject themselves to the discipline of the church, even to expulsion in extreme cases. We implore members to accept the advice and counsel of the church and abstain from all of the above. Since members are to be examples to the world (Romans 14:20–21) indulgence in any of these activities disqualifies then for Church or Sunday School work or as delegates to District or General Conference.[17]

The temperance movement gained early support from Methodists. The British Methodist Church historically promoted teetotalism; since the 1970s, it has encouraged members to consider abstinence from alcohol, but does allow responsible drinking.[19] The Church of the Nazarene and Wesleyan Methodist Church, both denominations in the Wesleyan tradition, teach abstinence.[20][21] Members of denominations in the conservative holiness movement, such as the Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection, are required to practice teetotalism.[22] The Book of Discipline of the Immanuel Missionary Church, a conservative Methodist denomination, states:[23]

Temperance is the moderate use of that which is beneficial, and a total abstinence from that which is harmful. Therefore no member shall be permitted to use or sell intoxicating liquors, tobacco, or harmful drugs, or to be guilty of things which are only for the gratification of the depraved appetite, and are unbecoming and inconsistent with our Christian profession (I Cor. 10:31). —General Standards, Immanuel Missionary Church[23]

Uniformed members of the Salvation Army ("soldiers" and "officers") make a promise on joining the movement to observe lifelong abstinence from alcohol. This dates back to the early years of the organisation, and the missionary work among alcoholics.[24]

With respect to Restorationist Christianity, members of certain groups within the Christian Science movement abstain from the consumption of alcohol.[citation needed]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints rejects alcohol based upon the Word of Wisdom.[25]

Eastern Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic Church, the Lutheran Churches, Oriental Orthodox Churches, and the Anglican Communion all require wine in their central religious rite of the Eucharist (Holy Communion). In contrast, churches in the Methodist tradition (which traditionally upholds teetotalism) require that "pure, unfermented juice of the grape" be used in the sacrament of Holy Communion.[26]

In the Gospel of Luke (1:13–15), the angel that announces the birth of John the Baptist foretells that "he shall be great in the sight of the Lord, and shall drink neither wine nor strong drink; and he shall be filled with the Holy Ghost, even from his mother's womb". A free translation of the New Testament, the Purified Translation of the Bible (2000), translates in a way that promotes teetotalism. However, the term 'wine' (and similar terms) being consumed by God's people occurs over two hundred times in both the Old and New Testament.[27]

Dharmic faiths

[edit]Jainism forbids the consumption of alcohol, in addition to trade in alcohol.[28][29]

In Hinduism, the consumption of alcohol and other intoxicants, called surāpāna, is considered the second mahāpātaka, or great sin.[30] Hindus are prohibited from drinking alcohol "as it has a direct impact on the nervous system, leading to actions that a sound person normally would not."[31]

Similarly, one of the five precepts of Buddhism is abstaining from intoxicating substances that disturb the peace and self-control of the mind, but it is formulated as a training rule to be assumed voluntarily by laypeople rather than as a commandment.[citation needed] Buddhist monks and nuns who hold traditional vows are forbidden from consuming alcohol.[citation needed]

Islam

[edit]In contemporary Islam, the concept of "khamr" (Arabic: خمر), which refers to a category of intoxicating substances that are forbidden, is now generally understood as encompassing all forms of alcohol. Muslim countries have low rates of alcohol consumption, with many enforcing a policy of prohibition. Additionally, the majority of Muslims do not drink and believe consuming alcohol is forbidden (haram).[32][33]

Ibn Majah and al-Tirmidhi narrated a hadith that if a Muslim drinks alcohol and does not repent, he would enter hell after death and be "made to drink from the pus of the people of Jahannum."[34]

Research on non-drinkers

[edit]Dominic Conroy and Richard de Visser published research in Psychology and Health that studied strategies used by college students who would like to resist peer pressure to drink alcohol in social settings. The research hinted that students are less likely to give in to peer pressure if they have strong friendships and make a decision not to drink before social interactions.[35]

A 2015 study by the Office for National Statistics showed that young Britons were more likely to be teetotallers than their parents.[36]

According to Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health, published by WHO in 2011, close to half of the world's adult population (45 percent) are lifetime abstainers. The Eastern Mediterranean Region, consisting of the Muslim countries in the Middle East and North Africa, is by far the lowest alcohol-consuming region in the world, both in terms of total adult per-capita consumption and prevalence of non-drinkers, i.e., 87.8 percent lifetime abstainers.[1]

Notable advocates

[edit]This is a list of notable figures who practiced teetotalism and were public advocates for temperance, teetotalism, or both. To be included in this list, individuals must be well-known for their abstention from alcohol, their advocacy efforts, or both. Individuals whose abstention from alcohol is not a defining characteristic or feature of their notability are intentionally excluded.

- Albert Barnes – American theologian, clergyman, abolitionist, temperance advocate, and author[37]

- George N. Briggs – 19th Governor of Massachusetts, from 1844 to 1851[38]

- Hugh Bourne – American clergyman and one of the joint founders of Primitive Methodism[39]

- Neal Dow – American Prohibition advocate and mayor of Portland, Maine, from 1851 to 1852 and from 1855 to 1856[40]

- Stuart Hamblen – American entertainer and Prohibition Party candidate for U.S. President in the 1952 presidential election[41]

- Lucy Webb Hayes – wife of Rutherford B. Hayes and first lady of the United States from 1877 to 1881[42]

- Carrie Nation – American who was a radical member of the temperance movement, which opposed alcohol before the advent of Prohibition. Nation is noted for attacking alcohol-serving establishments (most often taverns) with a hatchet.[43]

See also

[edit]- Alcoholics Anonymous

- Blue ribbon badge

- Catch-my-Pal

- Christianity and alcohol

- List of Temperance organizations

- Theobald Mathew (temperance reformer)

- Native American temperance activists

- Pioneer Total Abstinence Association

- Sobriety

- Sober curious

- Straight edge

- Temperance bar

- Woman's Christian Temperance Union

- Word of Wisdom

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Global status report on alcohol and health 2018". Who.int.

- ^ Blocker, Jack S. (2003). Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History: An International Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-57607-833-4.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary – T, page 5". Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ a b Kruth, Rebecca; Curzan, Anne (22 September 2019). "TWTS: Why "teetotaler" has nothing to do with tea". Michigan Radio. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Road to Zion – British Isles, BYU-TV; "BYUtv - Road to Zion: British Isles: Part One". Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ a b Gately, Iain (May 2009). Drink: A Cultural History of Alcohol. New York: Gotham Books. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-592-40464-3.

- ^ Cox, David J.; Stevenson, Kim; Harris, Candida; Rowbotham, Judith (12 June 2015). Public Indecency in England 1857–1960: 'A Serious and Growing Evil'. Routledge. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-317-57383-8.

- ^ Quinion, Michael. "Teetotal". Worldwidewords.org. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ^ An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language, by Walter William Skeat; published by Clarendon Press, 1893

- ^ Words and Their Ways, by James B. Greenough; published 1902

- ^ The Charleston Observer vol. 10, no. 44 (29 October 1836): 174, columns 4–5.

- ^ Hanson, David J. (14 August 2019). "Anti-Alcohol Industry 101: Overview of the Neo-Temperance Movement". Alcohol Problems and Solutions. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Lawson, Wilfrid (August 1893). "Prohibition in England". The North American Review. 157 (441): 152. JSTOR 25103180. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ "6 great things that happen to your body when you give up drinking". Cosmopolitan.com. 20 January 2016.

- ^ "Drink less this Lent". Pioneer Total Abstinence Association. 22 February 2009. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ Gilbert, Kathy L. (21 February 2012). "Could you go alcohol-free for Lent?". United Methodist News Service. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ a b Dunkard Brethren Church Polity. Dunkard Brethren Church. 1 November 2021. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Statement of Faith and Practice. Bakersville: Salem Amish Mennonite Church. 2012. p. 8.

- ^ "Temperance". Methodist Heritage. Methodist Church in Britain. Retrieved 18 January 2025.

- ^ Eastlack, Anita (2016). The discipline of the Wesleyan Church 2016 (PDF). Indianapolis, Indiana: Wesleyan Publishing House. ISBN 978-1-63257-198-4. OCLC 1080251593.

- ^ "2017-2021 Manual". Church of the Nazarene. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ The Discipline of the Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection (Original Allegheny Conference). Salem: Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection. 2014. p. 37.

- ^ a b Discipline of the Immanuel Missionary Church. Shoals, Indiana: Immanuel Missionary Church. 1986. p. 17.

- ^ "Positional Statement: Alcohol in Society". salvationarmy.org. The Salvation Army International. 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ^ "Why Mormons Don't Drink Alcohol, Tea, and Coffee?". pacific.churchofjesuschrist.org. Retrieved 19 November 2024.

- ^ Dunkle, William Frederick; Quillian, Joseph D. (1970). Companion to The Book of Worship. Abingdon Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-687-09258-1.

The pure, unfermented juice of the grape shall be used. The "fair white linen cloth" is merely a table covering that is appropriate for this central sacrament of the church.

- ^ Beavers, Keith (n.d.). "What Wine Would Jesus Drink?". VinePair. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Jain Journal, Volume 15. Jain Bhawan. 1981. p. 32.

- ^ Sharma, Arvind (1 October 2010). The World's Religions: A Contemporary Reader. Fortress Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8006-9746-4.

- ^ Klostermaier, Klaus K. (5 July 2007). A Survey of Hinduism: Third Edition. SUNY Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-7914-7082-4.

- ^ Agarwal, Anav (17 February 2023). "Lord Shiva, Hinduism & Substance Abuse". The Times of India. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ Michalak, Laurence; Trocki, Karen (1 June 1999). "Alcohol and Islam: An Overview". Contemporary Drug Problems. 33 (4): 523–562. doi:10.1177/009145090603300401. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "Nothing in the Quran Says Alcohol "is Haram": Saudi Author".

- ^ Desai, Mufti Siraj (9 May 2015). "Punishment for Drinking Alcohol". IslamQA.

- ^ Conroy, Dominic; de Visser, Richard (2014). "Being a non-drinking student: An interpretative phenomenological analysis". Psychology and Health. 29 (5): 536–551. doi:10.1080/08870446.2013.866673. ISSN 0887-0446. PMID 24245802. S2CID 7115520.

- ^ Neville, Sarah (13 February 2015). "Young Britons turning teetotal in growing numbers, survey says". Financial Times. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ "Albert Barnes". SwordSearcher. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Giddings, Edward Jonathan (1890). American Christian Rulers, or Religion and Men of Government. New York: Bromfield & Company. p. 66. OCLC 5929456.

- ^ "Papers of Hugh Bourne - Collection 68". Billy Graham Center Archives. Wheaton College. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017.

- ^ Dow, Neal (1898). The Reminiscences of Neal Dow: Recollections of Eighty Years. Portland, ME: Evening Express Pub. Co. p. 682. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "Stuart Hamblen, 80, Singer and Candidate (Obituary)". The New York Times. 9 March 1989. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ Gould, Lewis L., ed. (1996). American First Ladies: Their Lives and Their Legacy. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc. pp. 216, 224. ISBN 0815314795.

- ^ "Hatchet job on drink was a right Carrie on". WalesOnline. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of teetotal at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of teetotal at Wiktionary