Isisaurus

| Isisaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian),

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Life restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Clade: | †Titanosauria |

| Clade: | †Lithostrotia |

| Genus: | †Isisaurus Wilson & Upchurch, 2003 |

| Species: | †I. colberti

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Isisaurus colberti (Jain & Bandyopadhyay, 1997)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Isisaurus (named after the Indian Statistical Institute) is a genus of titanosaurian dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Lameta Formation of India and Pab Formation of Pakistan. The genus contains a single species, Isisaurus colberti.

Discovery and Naming

[edit]The type specimen of Isisaurus colberti, ISI R 335/1-65, was originally described and named as Titanosaurus colberti by Sohan Lal Jain and Saswati Bandyopadhyay in 1997. The specific name honours Edwin Harris Colbert.[1][2] In 2003, the fossils were designated as belonging to its own genus by Wilson and Upchurch.[3] The generic name, "Isisaurus," combines a reference to the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) with the Greek "saurus," meaning "lizard." It had a short, vertically directed neck and long forelimbs,[citation needed] making it considerably different from other sauropods. The humerus is 148 centimetres long.[1]

The site locality is Dongargaon Hill, which is in a Maastrichtian crevasse splay claystone in the Lameta Formation of India.[2] Dongargaon Hill (20.212318N,79.090709E) is located near Warora, in Chandrapur District, Maharashtra.

A braincase referrable to the species is known from the Pab Formation of Pakistan, which is equivalent in age to the Lameta Formation.[4]

Isisaurus is known from better remains than many other titanosaurs that were known at the time of its description. Much of its postcranial skeleton is known. The skeletal material found by Jain and Bandyopadhyay between 1984 and 1986 was "in associated and mostly articulated condition." The holotype includes cervical, dorsal, sacral and caudal vertebrae, ribs, pelvis, scapula, coracoid, left forelimb and other bones. No skull, hindlimb, or foot bones are known.[1] Since the original description of Isisaurus, unrelated titanosaur fossils belonging to more complete individuals have been discovered elsewhere.[5][6]

Description

[edit]

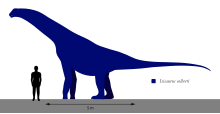

Isisaurus was a medium-sized sauropod, with some estimates of its body length up to 18 metres (59 ft) long and weighing 15 metric tons (17 short tons).[7] The angle between the occipital bone and occipital condyle in Isisaurus and the fellow Indian titanosaur Jainosaurus is different. In the specimen from Dongargaon it is equal to 120°. In that matter, the cranium of Isisaurus resembles the skulls of Diplodocus and Apatosaurus (genera belonging to the Diplodocidae), but the bone modifications are different.[8]

Classification

[edit]While Isisaurus has consistently been considered to be a titanosaurian sauropod, its exact placement within this clade and its relationships with other titanosaurs has been controversial and problematic. Most analyses have recovered it with close affinities to taxa such as Rapetosaurus or the Saltasauridae. Various alternative positions suggested in that past are displayed in the following cladograms:

Isisaurus was placed within Opisthocoelicaudiinae by Curry-Rogers in 2005.[9]

The cladogram below follows Zaher et al. (2011).[10]

In 2017, Isisaurus was recovered as the sister taxon to Tapuiasaurus.[11]

In 2021, Isisaurus was placed as the sister taxon to Arackar. The cladogram from Rubilar-Rogers et al. (2021) is shown below:[12]

Palaeobiology

[edit]Fungus in coprolites believed to have been voided by Isisaurus indicate that it ate leaves from several species of tree, since these fungi are known to be pathogens which infect tree leaves.[13]

Paleoecology

[edit]

Isisaurus lived in the area belonging nowadays to India during the Maastrichtian age of the Cretaceous period.[14][15] Its remains are the most complete among the Cretaceous dinosaurs known from that region.[16] Khosla et al. (2003) listed the following Indian sauropods:[17]

- Titanosaurus indicus

- T. blanfordi

- T. rahiolensis

- Jainosaurus septentrionalis.

Wilson et al. (2009) listed only two Indian titanosaurs, Isisaurus and its distant relative, Jainosaurus. Isisaurus and Jainosaurus lived sympatrically in the area of middle and western India. Isisaurus fossils have also been reported from western Pakistan.[8]

Other dinosaurs, including the abelisaurs Indosuchus, Rahiolisaurus, and Rajasaurus, also existed in the Lameta Formation.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Jain, Sohan L.; Bandyopadhyay, Saswati (1997). "New Titanosaurid (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Central India". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (1). Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma: 114. Bibcode:1997JVPal..17..114J. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10010958.

- ^ a b "Isisaurus colberti". Paleobiology Database. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ^ Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Upchurch, P. (2003). "A revision of Titanosaurus Lydekker (Dinosauria – Sauropoda), the first dinosaur genus with a 'Gondwanan' distribution" (PDF). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 1 (3). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press: 125–160. Bibcode:2003JSPal...1..125W. doi:10.1017/s1477201903001044. S2CID 53997295. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ^ Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Barrett, Paul M.; Carrano, Matthew T. (September 2011). "An associated partial skeleton of Jainosaurus cf. septentrionalis (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Chhota Simla, Central India". Palaeontology. 54 (5): 981–998. Bibcode:2011Palgy..54..981W. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01087.x. hdl:2027.42/86940. S2CID 55975792.

- ^ Lacovara, Kenneth J.; Lamanna, Matthew C.; Ibiricu, Lucio M.; Poole, Jason C.; Schroeter, Elena R.; Ullmann, Paul V.; Voegele, Kristyn K.; Boles, Zachary M.; Carter, Aja M.; Fowler, Emma K.; Egerton, Victoria M. (2014-09-04). "A Gigantic, Exceptionally Complete Titanosaurian Sauropod Dinosaur from Southern Patagonia, Argentina". Scientific Reports. 4 (1): 6196. doi:10.1038/srep06196. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5385829. PMID 25186586.

- ^ Carballido, José L.; Pol, Diego; Otero, Alejandro; Cerda, Ignacio A.; Salgado, Leonardo; Garrido, Alberto C.; Ramezani, Jahandar; Cúneo, Néstor R.; Krause, Javier M. (2017-08-16). "A new giant titanosaur sheds light on body mass evolution among sauropod dinosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 284 (1860): 20171219. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.1219. PMC 5563814. PMID 28794222.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-78684-190-2. OCLC 985402380.

- ^ a b Jeffrey A. Wilson, Michael D. D'emic, Kristina A. Curry Rogers, Dhananjay M. Mohabey & Subashis Sen (2009). "A reassessment of the sauropod dinosaur Jainosaurus (="Antarctosaurus") septentrionalis from the Upper Cretaceous of India". Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan. 32 (2): 17–40. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Curry Rogers, Kristina; Wilson, Jeffrey A. (2005). The Sauropods: evolution and paleobiology. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24623-2.

- ^ Zaher, Hussam; Pol, Diego; Carvalho, Alberto B.; Nascimento, Paulo M.; Riccomini, Claudio; Larson, Peter; Juarez-Valieri, Rubén; Pires-Domingues, Ricardo; da Silva, Nelson Jorge; de Almeida Campos, Diógenes (2011-02-07). Sereno, Paul (ed.). "A Complete Skull of an Early Cretaceous Sauropod and the Evolution of Advanced Titanosaurians". PLOS ONE. 6 (2): e16663. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...616663Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016663. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3034730. PMID 21326881.

- ^ Carballido, José L.; Pol, Diego; Otero, Alejandro; Cerda, Ignacio A.; Salgado, Leonardo; Garrido, Alberto C.; Ramezani, Jahandar; Cúneo, Néstor R.; Krause, Javier M. (2017-08-16). "A new giant titanosaur sheds light on body mass evolution among sauropod dinosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 284 (1860): 20171219. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.1219. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 5563814. PMID 28794222.

- ^ Rubilar-Rogers, D.; Vargas, A. O.; González Riga, B.; Soto-Acuña, S.; Alarcón-Muñoz, J.; Iriarte-Díaz, J.; Arévalo, C.; Gutstein, C. S. (2021). "Arackar licanantay gen. et sp. nov. a new lithostrotian (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Atacama Region, northern Chile". Cretaceous Research. 124: Article 104802. Bibcode:2021CrRes.12404802R. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104802. S2CID 233780252.

- ^ Sharma, N., Kar, R.K., Agarwal, A. and Kar, R. (2005). "Fungi in dinosaurian (Isisaurus) coprolites from the Lameta Formation (Maastrichtian) and its reflection on food habit and environment." Micropaleontology, 51(1): 73-82.

- ^ Wilson, J. A. (2006). "An Overview of Titanosaur Evolution and Phylogeny" (PDF). Actas de las III Jornadas Internacionales Sobre Paleontología de Dinosaurios y Su Entorno, Salas de los Infantes, Burgos. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ González Riga, Bernardo J. (2005). "Nuevos restos fósiles de Mendozasaurus neguyelap (Sauropoda, Titanosauria) del Cretácico Tardío de Mendoza, Argentina" [New fossil remains of Mendozasaurus neguyelap (Sauropoda, Titanosauria) of the Late Cretaceous of Mendoza, Argentina]. Ameghiniana (in Spanish). 42 (3): 535–548. ISSN 0002-7014. English translation by Michael D'Emic

- ^ Jeffrey A. Wilson, Paul C. Sereno, Suresh Srivastava, Devendra K. Bhatt (2003-08-15). "A New Abelisaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) Grom The Lameta" (PDF). Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology. 31 (1). The University of Michigan: 1–42. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Khosla, A., V. V. Kapur, P. C. Sereno, J. A. Wilson, G. P. Wilson, D. Dutheil, A. Sahni, M. P. Singh, S. Kumar (2003). "First dinosaur remains from the Cenomanian-Turonian Nimar Sandstone (Bagh Beds), district Dhar, Madhya Pradesh, India" (PDF). Journal of the Palaeontogical Society of India. 48: 115–127. doi:10.1177/0971102320030108. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)