Embolotherium

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Embolotherium Temporal range: Late Eocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| E. andrewsi skull at the AMNH | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | †Brontotheriidae |

| Infratribe: | †Embolotheriita |

| Genus: | †Embolotherium Osborn, 1929 |

| Type species | |

| *Embolotherium andrewsi Osborn, 1929

| |

| Species | |

| |

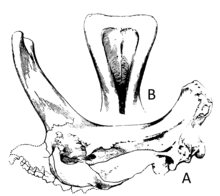

Embolotherium (Greek ἐμβωλή, embolê + θηρίον, thêrion "battering ram beast", or "wedge beast") is an extinct genus of brontothere that lived in Mongolia during the late Eocene epoch. It is most easily recognized by a large bony protuberance emanating from the anterior (front) of the skull.[1] This resembles a battering ram, hence the name Embolotherium. The animal is known from about 12 skulls, several jaws, and a variety of other skeletal elements from the Ulan Gochu formation of Inner Mongolia as well as the Ergilin Dzo Formation of Outer Mongolia.

Taxonomy

[edit]

Several species of Embolotherium have been named, including Embolotherium andrewsi, Embolotherium grangeri, Embolotherium louksi, Embolotherium ultimum, Embolotherium ergilensi, and Embolotherium efremovi. However, only two species, Embolotherium andrewsi and Embolotherium grangeri, appear to be valid. Other supposed species of Embolotherium are probably synonymous with these two species and were originally based on juvenile skulls, poorly preserved fossil material, or specimens that are not significantly different from either E. andrewsi or E. grangeri.

Another genus of brontothere, Titanodectes, which was named for several lower jaws found in the same sedimentary deposits as Embolotherium, probably represents the same beast as Embolotherium grangeri. Protembolotherium is another closely related genus from the Middle Eocene, which is distinguished by a noticeably smaller ram.

Description

[edit]

The skull reaches a condylobasal length of 920 mm. Complete skeletons of Embolotherium have not yet been recovered, although many postcranial elements referable to it have been collected. The postcranial skeleton of Embolotherium suggests a powerful, graviportal animal with a close resemblance to the late Eocene North American brontothere Megacerops, which it rivaled or somewhat exceeded in size, making Embolotherium one of the largest brontotheres, if not the largest.[2][3][4] Unlike many of the other Late Eocene brontotheres, there is no clear evidence that Embolotherium was sexually dimorphic. All known specimens have large rams. Therefore, coupled with the fact that the rams were hollow and fragile in comparison to the solid and sturdy horns of the North American brontotheres, such as Megacerops, it does not seem likely that the ram served as a weapon for contests between males. Rather, it might have had a non-sexual function, such as signaling to each other. The ram may have served as a specialized resonator for sound production. This hypothesis is suggested by the fact that the bony nasal cavity extends to the peak of the ram, thus implying that the nasal chamber was greatly elevated, possibly creating a resonating chamber.

References

[edit]- ^ Osborn, H.F. 1929. Embolotherium, gen. nov., of the Ulan Gochu, Mongolia. American Museum Novitates; no. 353

- ^ Osborn, Henry Fairfield (1929). "Embolotherium, Gen. Nov., Of The Ulan Gochu, Mongolia". American Museum Novitates (353).

- ^ Mihlbachler, Matthew C. (2008). "Species Taxonomy, Phylogeny, and Biogeography of the Brontotheriidae (Mammalia: Perissodactyla)". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 2008 (311): 1–475. doi:10.1206/0003-0090(2008)501[1:STPABO]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Benjamin McLaughin, Matthew C. Mihlbachler and Mick Ellison: The postcranial skeleton of Embolotherium (Brontotheriidae) from the Middle and Late Eocne of Central Asia. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (suppl.), 2010, S. 132A–133A.

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2009) |

- Barry Cox, Colin Harrison, R.J.G. Savage, and Brian Gardiner. (1999): The Simon & Schuster Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Creatures: A Visual Who's Who of Prehistoric Life. Simon & Schuster.

- David Norman. (2001): The Big Book of Dinosaurs. page 204, Walcome books.