Thomas de Brantingham

Thomas de Brantingham | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Exeter | |

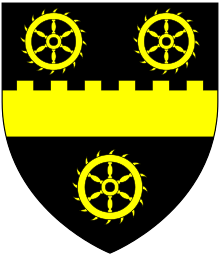

Seal of Thomas de Brantingham as Bishop of Exeter. The Bishop is the small standing figure below the enthroned king (Edward III or Richard II) | |

| Appointed | 5 March 1370 |

| Term ended | 23 December 1394 |

| Predecessor | John Grandisson |

| Successor | Edmund Stafford |

| Other post(s) | Lord Treasurer Keeper of the Wardrobe |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 12 May 1370 |

| Personal details | |

| Died | 23 December 1394 |

| Buried | Nave of Exeter Cathedral |

| Nationality | English |

Thomas de Brantingham | |

|---|---|

| Lord Treasurer | |

| In office 27 June 1369 – 27 March 1371 | |

| Monarch | Edward III |

| Preceded by | John Barnet |

| Succeeded by | Richard Scrope |

| In office 19 July 1377 – 1 February 1381 | |

| Monarch | Richard II |

| Preceded by | Henry Wakefield |

| Succeeded by | Robert Hales |

| In office 4 May 1389 – 20 August 1389 | |

| Monarch | Richard II |

| Preceded by | John Gilbert |

| Succeeded by | John Gilbert |

Thomas de Brantingham (died 1394) was an English clergyman who served as Lord Treasurer to Edward III and on two occasions to Richard II, and as bishop of Exeter from 1370 until his death. De Brantingham was a member of the Brantingham family of North East England.

Edward III obtained preferment for him in the church, and from 1361 to 1368 he was employed in France in responsible positions. At an early stage in de Brantingham's career, de Brantingham served as Keeper of the Wardrobe.[2] He was closely associated with William of Wykeham, and while the latter was in power as chancellor,[3] Brantingham was Lord Treasurer to Edward III (from 1369 to 1371), and on two later occasions to Richard II (from 1377 to 1381; and in 1389),[2][4] being appointed Bishop of Exeter on 5 March 1370 and consecrated as such on 12 May 1370.[5] De Brantingham died in December 1394, probably on the 23rd,[5] and was buried in the nave of Exeter Cathedral.[6]

Administrator

[edit]By 1349 he had been appointed as clerk of the exchequer. In 1359 he was cofferer responsible for finance during the French military campaign and from 1361 to 1368 he was Treasurer of Calais. On 27 June 1369 he was appointed treasurer of the realm, but as the war in France deteriorated, he, along with fellow clerics William of Wykeham, the Chancellor and Peter Lacy, Keeper of the Privy Seal, was forced by public opinion to resign. However, in 1370 he had been consecrated as Bishop of Exeter.

Bishop of Exeter

[edit]While serving as bishop of Exeter, de Brantingham was petitioned by parishioners of "St. Tenion" (which, it has been suggested, may refer to Tinney Hall near Lewannick, Cornwall)[7] in the peculiar jurisdiction of St German's, concerning a suit carried on by them for eighteen years against the Prior and Convent of St. German's about permission for them to have their own chaplain.[7] The petitioners sought de Brantingham's intervention to settle the dispute,[7] although his decision is now lost.

Personal life

[edit]A record of de Brantingham's death, dated 13 December 1394, notes that the bishop was to be buried in the nave of Exeter Cathedral and lists, among the beneficiaries of his will, Richard Brantingham and his wife, Joan (presumably de Brantingham's son and daughter-in-law).[6] Nor did De Brantingham forget the village of Brantingham, which had given its name to his family, bequeathing to the church of Brantingham a pair of vestments or one shilling.[6] De Brantingham also left a book of decretals to each of Merton Hall and Stapledon Hall. De Brantingham's association with Stapledon Hall (now Exeter College, Oxford) pre-dated his death to his contribution of 20 pounds to the building of its library.[6][8] As proof of his position in society, de Brantingham also remembered in (or had as a witness to) his will William Hankeford, later Chief Justice of the King's Bench.[6]

Richard Brantingham is recorded in the survey of Thomas Hatfield, Bishop of Durham, completed in 1382,[9] as a "suiter" or lawyer, holding a half a burgage for life in Auckland and paying six pence for any omission, and one penny at the four terms.[10] Bishop Hatfield granted a forest office to the valet of his kitchen, Walter Brantingham, presumably a relation.[11]

External links

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Pole, Sir William (d.1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791, p.473

- ^ a b Steel: 419

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 431.

- ^ Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 105

- ^ a b Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 246

- ^ a b c d e Surtees: 248

- ^ a b c Yonge, Record 107/915

- ^ Savage: 150

- ^ Greenwell: vii

- ^ Greenwell: 165

- ^ Holford and Stringer: 100

References

[edit]- Davies, R.G. "Brantingham, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32787. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Greenwell, William, ed. (1857), Bishop Hatfield's survey, Publications of the Surtees Society, Durham: Surtees Society.

- Holford, M. L.; Stringer, K. J. (2010), Border liberties and loyalties: North-East England, c. 1200 – c. 1400, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 9780748632787.

- Savage, Ernest Albert (1911), Old English libraries, Taylor & Francis.

- Steel, Anthony Bedford (1954), The receipt of the Exchequer, 1377–1485, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- North country wills, Publications of the Surtees Society, vol. 116, Surtees Society, 1908

- Yonge family of Puslinch, Devon (n.d.), Records, Plymouth and West Devon Public Records Office.

- Pollard, Albert Frederick (1901). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.