The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening

| The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening | |

|---|---|

| A sword stands over a shield, and goes through the letter "Z" in the title "The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening". European Game Boy box art | |

| Developer(s) | Nintendo Entertainment Analysis & Development |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Director(s) | Takashi Tezuka |

| Producer(s) | Shigeru Miyamoto |

| Programmer(s) |

|

| Artist(s) | Yoichi Kotabe |

| Writer(s) | |

| Composer(s) |

|

| Series | The Legend of Zelda |

| Platform(s) | Game Boy, Game Boy Color |

| Release | Game Boy Game Boy Color |

| Genre(s) | Action-adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening[a] is a 1993 action-adventure video game developed by Nintendo Entertainment Analysis & Development and published by Nintendo for the Game Boy. It is the fourth installment in The Legend of Zelda series, and the first for a handheld game console.

Link's Awakening began as a port of the Super NES title The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, developed after-hours by Nintendo staff. It grew into an original project under the direction of Takashi Tezuka, with a story and script created by Yoshiaki Koizumi and Kensuke Tanabe. It is one of the few Zelda games not to take place in the land of Hyrule, and does not feature Princess Zelda or the Triforce relic. Instead, protagonist Link begins the game stranded on Koholint Island, a place guarded by a creature called the Wind Fish. Assuming the role of Link, the player fights monsters and solves puzzles while searching for eight musical instruments that will awaken the sleeping Wind Fish and allow him to escape from the island.

Link's Awakening was critically and commercially successful. Critics praised the game's depth and number of features; complaints focused on its control scheme and monochrome graphics. An updated re-release titled The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening DX[b] was released for the Game Boy Color in 1998 featuring color graphics, compatibility with the Game Boy Printer, and an exclusive color-based dungeon. Together, the two versions of the game have sold more than six million units worldwide, and have appeared on multiple game publications' lists of the best games of all time.

Plot

Setting and characters

Unlike most The Legend of Zelda titles, Link's Awakening is set outside the kingdom of Hyrule. It omits locations and characters from previous games, aside from protagonist Link and a passing mention of Princess Zelda.[9][10] Instead, the game takes place entirely on Koholint Island,[9] an isolated landmass cut off from the rest of the world. The island, though small, contains a large number of secrets and interconnected pathways.[11]

In Link's Awakening, the player is given advice and directions by non-player characters such as Ulrira, a shy old man who communicates with Link exclusively by telephone. The game contains cameo appearances by characters from other Nintendo titles, such as Wart, Yoshi, Kirby, Dr. Wright (renamed Mr. Write) from the Super NES version of SimCity, and the exiled prince Richard from Kaeru no Tame ni Kane wa Naru.[12][13][14] Chomp, an enemy from the Mario series, was included after a programmer gave Link the ability to grab the creature and take it for a walk. Enemies from Super Mario Bros. such as Goombas also appear in underground side-scrolling sections; Link may land on top of them much as with Super Mario Bros., or he can attack them in the usual way: the two methods yield different bonuses. Director Takashi Tezuka said that the game's "freewheeling" development made Link's Awakening seem like a parody of The Legend of Zelda series.[13] Certain characters in the game break the fourth wall; for example, little children inform the player of game mechanics such as saving, but admit that they do not understand the advice they are giving.[15]

Plot

After the events of Oracle of Ages and Oracle of Seasons,[16] the hero Link travels abroad to train for further threats. A storm destroys his boat at sea, and he washes ashore on Koholint Island,[17] where he is taken to the house of Tarin and his daughter Marin. She is fascinated by Link and the outside world, and tells Link wistfully that, if she were a seagull, she would leave and travel across the sea.[18] After Link recovers his sword, a mysterious owl tells him that he must wake the Wind Fish, Koholint's guardian, in order to return home. The Wind Fish lies dreaming in a giant egg on top of Mt. Tamaranch, and can only be awakened by the eight Instruments of the Sirens.

Link proceeds to explore a series of dungeons in order to recover the eight instruments. During his search for the sixth instrument, Link goes to the Ancient Ruins. There he finds a mural that details the reality of the island: that it is merely a dream world created by the Wind Fish.[19] After this revelation, the owl tells Link that this is only a rumor, and only the Wind Fish knows for certain whether it is true. Throughout Koholint Island, nightmare creatures attempt to obstruct Link's quest for the instruments, as they wish to rule the Wind Fish's dreamworld.

After collecting all eight instruments from the eight dungeons across Koholint, Link climbs to the top of Mt. Tamaranch and plays the Ballad of the Wind Fish.[20] This breaks open the egg in which the Wind Fish sleeps; Link enters and confronts the last evil being, a Nightmare that takes the form of Ganon and other enemies from Link's past.[21] Its final transformation is "DethI", a cyclopean, dual-tentacled Shadow.[22][23] After Link defeats DethI, the owl reveals itself to be the Wind Fish's guardian, and the Wind Fish explains that Koholint is all Link's dream. When Link plays the Ballad of the Wind Fish again, he and the Wind Fish awaken; Koholint Island and all its inhabitants slowly disappear.[24] Link finds himself lying on driftwood in the middle of the ocean, with the Wind Fish flying overhead. If the player did not lose any lives during the game, Marin is shown flying after the ending credits finish[25] - she is shown in the form of a winged woman when played in the original black and white format, while she takes the form of a seagull if played with color in the DX version.

Gameplay

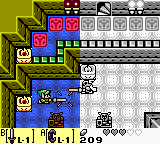

Like most games in The Legend of Zelda series, Link's Awakening is an action-adventure game focused on exploration and combat.[26] The majority of the game takes place from an overhead perspective.[9] The player traverses the overworld of Koholint Island while fighting monsters and exploring underground dungeons. Dungeons steadily become larger and more difficult, and feature "Nightmare" boss characters that the player must defeat, taking different forms in each dungeon, and getting harder to defeat each time.[20] Success earns the player heart containers, which increase the amount of damage the player character can survive; when all of the player's heart containers have been emptied, the game restarts at the last doorway entered by the character. Defeating a Nightmare also earns the player one of the eight instruments necessary to complete the game.[20]

Link's Awakening was the first overhead-perspective Zelda game to allow Link to jump; this enables sidescrolling sequences similar to those in the earlier Zelda II: The Adventure of Link.[9] Players can expand their abilities with items, which are discovered in dungeons and through character interactions. Certain items grant access to previously inaccessible areas, and are needed to enter and complete dungeons. The player may steal items from the game's shop, but doing so changes the player character's name to "THIEF" for the rest of the game and causes the shopkeeper to knock out the character upon re-entry of the shop.[9]

In addition to the main quest, Link's Awakening contains side-missions and diversions. Collectible "secret seashells" are hidden throughout the game; when twenty of these are found, the player can receive a powerful sword that fires energy beams when the player character is at full health, similar to the sword in the original The Legend of Zelda. Link's Awakening is the first Zelda game to include a trading sequence minigame: the player may give a certain item to a character, who in turn gives the player another item to trade with someone else.[20] It is also the first game in the Zelda series in which the A and B buttons may be assigned to different items, which enables more varied puzzles and item combinations.[9] Other series elements originating in Link's Awakening include fishing, and learning special songs on an ocarina; the latter mechanic is central to the next Zelda game released, Ocarina of Time.[27]

Development

Link's Awakening began as an unsanctioned side project; programmer Kazuaki Morita created a Zelda-like game with one of the first Game Boy development kits, and used it to experiment with the platform's capabilities. Other staff members of the Nintendo Entertainment Analysis and Development division joined him after-hours, and worked on the game in what seemed to them like an "afterschool club". The results of these experiments with the Game Boy started to look promising, and following the 1991 release of the Super NES video game The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, director Takashi Tezuka asked permission to develop a handheld Zelda title; he intended it to be a port of A Link to the Past, but it evolved into an original game.[3] The majority of the team that had created A Link to the Past was reassembled to advance this new project. Altogether, it took them one and a half years to develop Link's Awakening.[28]

Tezuka recalled that the early free-form development of Link's Awakening resulted in the game's "unrestrained" contents, such as the unauthorized cameo appearances of characters from the Mario and Kirby series.[13] A Link to the Past script writer Kensuke Tanabe joined the team early on, and came up with the basis of the story.[13][29] Tezuka sought to make Link's Awakening a spin-off, and gave Tanabe instructions to omit common series elements such as Princess Zelda, the Triforce relic, and the setting Hyrule.[29] As a consequence, Tanabe proposed his game world idea of an island with an egg on top of a mountain.[29]

Later on, Yoshiaki Koizumi, who had previously helped with the plot of A Link to the Past, was brought into the team.[13][28] Koizumi was responsible for the main story of Link's Awakening, provided the idea of the island in a dream, and conceived the interactions with the villagers.[29][30][31] Link's Awakening was described by series producer Eiji Aonuma as the first Zelda game with a proper plot, which he attributed to Koizumi's romanticism.[32] Tezuka intended the game's world to have a similar feeling to the American television series Twin Peaks, which, like Link's Awakening, features characters in a small town.[13] He suggested that the characters of Link's Awakening be written as "suspicious types", akin to those in Twin Peaks—a theme which carried over into later Zelda titles.[32] Tanabe created these "odd" characters; he was placed in charge of the subevents of the story, and wrote almost all of the character dialog, with the exception of the owl's and the Wind Fish's lines.[13][29] Tanabe implemented a previous idea of the world ending when a massive egg breaks on top of a mountain; this idea was originally meant for A Link to the Past. Tanabe really wanted to see this idea in a game and was able to implement it in Link's Awakening as the basic concept.[33]

Masanao Arimoto and Shigefumi Hino designed the game's characters, while Yoichi Kotabe served as illustrator.[34] Save for the opening and the ending, all pictures in the game were drawn by Arimoto.[29] Yasahisa Yamamura designed the dungeons, which included the conception of rooms and routes, as well as the placement of enemies.[29] Shigeru Miyamoto, who served as the producer of Link's Awakening, did not provide creative input to the staff members. However, he participated as game tester, and his opinions greatly influenced the latter half of the development.[28]

The music for Link's Awakening was composed by Minako Hamano and Kozue Ishikawa, for whom it was their first game project.[28] Kazumi Totaka was responsible for the sound programming and all sound effects.[28] As with most Zelda games, Link's Awakening includes a variation of the recurring overworld music;[35] the Game Boy arrangement of this theme, titled "Field", was created by Ishikawa.[36] The staff credits theme, "Yume o Miru Shima e" was later arranged for orchestra by Yuka Tsujiyoko, and performed at the Orchestral Game Music Concert 3 in 1993.[37] Super Smash Bros. Brawl includes a remix of the game's "Tal Tal Heights" theme.[38]

In an interview about the evolution of the Zelda series, Aonuma called Link's Awakening the "quintessential isometric Zelda game".[39] At another time, he stated that, had the game not come after A Link to the Past, Ocarina of Time would have been very different.[32] Several elements from Link's Awakening were re-used in later Zelda titles; for example, programmer Morita created a fishing minigame that reappeared in Ocarina of Time, among others. Tanabe implemented a trading sequence; Tezuka compared it to the Japanese Straw Millionaire folktale, in which someone trades up from a piece of straw to something of greater value. This concept also appeared in most sequels.[13]

Releases

To support the North American release of Link's Awakening, Nintendo sponsored a crosscountry train competition called the Zelda Whistle Stop Tour.[40] The event, which lasted three days, allowed select players to test Link's Awakening in a timed race to complete the game.[41] The event was meant not only to showcase the game, but also the Game Boy's superior battery life and portability, the latter of which was critical to the accessibility of a portable Zelda title.[9][40] The company-owned magazine Nintendo Power published a guide to the game's first three areas in its July 1993 issue.[12]

In 1998, to promote the launch of the Game Boy Color, Nintendo re-released Link's Awakening as The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening DX. It features fully colorized graphics and is backward compatible with the original Game Boy. Link's Awakening DX contains a new optional dungeon, with unique enemies and puzzles based on color (due to this the dungeon cannot be accessed on the earlier non-color Game Boy models).[11] After completing the dungeon, the player may choose to receive either a red or blue tunic, which increase attack and defense, respectively. The DX version also allows players to take photos after the player visits a camera shop, its owner will appear in certain locations throughout the game. A total of twelve photos can be taken, which may be viewed at the shop, or printed with the Game Boy Printer accessory.[11][42] For Link's Awakening DX, Tezuka returned as project supervisor, with Yoshinori Tsuchiyama as the new director.[29] Nobuo Matsumiya collaborated with Tsuchiyama on applying changes to the original script; for example, hint messages were added to the boss battles.[29] For the new dungeon, Yuichi Ozaki created a musical piece based on Kondo's dungeon theme from the original The Legend of Zelda.[29][43]

In 2010, Nintendo announced that the DX version would be re-released on the Virtual Console of the Nintendo 3DS,[44] and became available June 2011. In July 2013, Link's Awakening DX was offered as one of several Virtual Console games which "elite status" members of the North America Club Nintendo could redeem as a free gift.[45]

Reception

| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| GameRankings | 91.23%[46] 90.39% (DX)[47] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| AllGame | |

| GameSpot | 8.7/10 (DX)[49] |

| IGN | 10/10 (DX)[26] |

| Nintendo Power | 4.18/5[50] |

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| Nintendo Power | Graphics and Sound, Challenge, Play Control, Best Overall[50] 56th Best Nintendo Game[51] |

| IGN | Reader's 40th Best Game of all time[52] Staff's 78th Best Game of all time[53] |

| Electronic Gaming Monthly | Best Game Boy Game of 1993[54] Editor's Choice Award (DX)[54] |

Link's Awakening was critically acclaimed, and holds an average score of 90% on aggregate site GameRankings.[46] In a retrospective article, Electronic Gaming Monthly writer Jeremy Parish called Link's Awakening the "best Game Boy game ever, an adventure so engrossing and epic that we can even forgive the whole thing for being one of those 'It's all a dream!' fakeouts".[55] Game Informer's Ben Reeves called it the third best Game Boy game and called it influential.[56] The Washington Post's Chip Carter declared that Nintendo had created a "legend that fits in the palm of your hand", and praised its portability and depth.[57] An Jōkiri of ITMedia echoed similar comments.[58] A writer for the Mainichi Shimbun enjoyed the game's music and story.[59] Multiple sources touted it as an excellent portable adventure for those without the time for more sophisticated games.[60][61]

Complaints about the game included its monochrome graphics; certain critics believed that they made it difficult to discern the screen's contents,[62] and wished that the game was in color. Critic William Burrill dismissed the game's visuals as "Dim Boy graphics [that are] nothing to write home about".[63] Both Carter and The Ottawa Citizen's Bill Provick found the two-button control scheme awkward, as they needed to switch items on almost every screen.[57][62] The Vancouver Sun's Katherine Monk called the dialogue "stilted", but considered the rest of the game to be "ever-surprising".[64]

Link's Awakening DX also received positive reviews; based on ten media outlets, it holds an average score of 92% on Game Rankings.[47] IGN's Adam Cleveland awarded the game a perfect score, and noted that "throughout the color-enhanced version of Zelda DX, it can easily be inferred that Nintendo has reworked its magic to fit new standards", by adding new content while keeping the original game intact.[26] Cameron Davis of GameSpot applauded the game's camera support and attention to detail in coloration and style,[49] while reviewers for the Courier Mail believed that the camera added gameplay depth and allowed players to show off trophies.[65] The Daily Telegraph's Samantha Amjadali wrote that the addition of color made the game easier by reducing deaths caused by indistinct graphics.[66] Total Games noted that the new content added little to the game, but found it addictive to play nonetheless.[67]

Link's Awakening sold well, and helped boost Game Boy sales 13 percent in 1993—making it one of Nintendo's most profitable years in North America up to that time.[68] The game remained on bestseller lists for more than 90 months after release,[69] and went on to sell 3.83 million units by 2004. The DX version sold another 2.22 million units.[70]

The game won several awards, including those in the Game Boy categories for Graphics and Sound, Challenge, Theme and Fun, Play Control, and Best Overall in the reader-chosen 1993 Nintendo Power Awards.[50] It was awarded Best Game Boy Game of 1993 by Electronic Gaming Monthly.[54] Nintendo Power later named it the fifty-sixth best Nintendo game,[51] and, in August 2008, listed the DX version as the second best Game Boy or Game Boy Color game.[71] IGN's readers ranked it as the 40th best game of all time, while the staff placed it at 78th;[52][53] the staff believed that, "while handheld spin-offs are generally considered the low point for game franchises, Link's Awakening proves that they can offer just as rich a gameplay experience as their console counterparts".[53] The game took 42nd place on the Guinness World Records' 2009 list of the top 50 most important and influential video games of all time.[72]

References

- Citations

- ^ "Game Boy (original) Games" (PDF). Nintendo of America Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 17, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ ゼルダの伝説 夢をみる島 (in Japanese). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Retrieved March 26, 2009.

- ^ a b "Iwata Asks: Zelda Handheld History – Like an Afterschool Club". Nintendo of Europe GmbH. Archived from the original on January 17, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening (1993) Game Boy release dates - MobyGames: "Country: United Kingdom - Release Date: Nov 18, 1993"

- ^ Mega Fun 11/1993 (German magazine; Scan @ Kultboy.com): "Erscheinungstermin: November" (Release date: November)

- ^ "The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening DX". Nintendo of Europe GmbH. Archived from the original on January 18, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Zeldaの伝説 – Introduction" (in Japanese). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Archived from the original on January 16, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ "Guide 64: Game Boy Release Schedule". Archived from the original on October 9, 1999.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Zelda Retrospective Part 2". GameTrailers. MTV Networks. October 20, 2006. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ Nintendo Co., Ltd (December 1, 1998). The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening DX. Nintendo of America Inc.

Marin: I thought you'd never wake up! You were tossing and turning... What? Zelda? No, my name's Marin!

- ^ a b c Vestal, Andrew; O'Neill, Cliff; Shoemaker, Brad. "History of Zelda". GameSpot. CBS Interactive Inc. p. 11. Archived from the original on December 21, 2005. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- ^ a b "'The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening' Guide". Nintendo Power. 1 (50). Nintendo of America Inc: 57–66. July 1993.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "2. Kirby and Chomps in Zelda".

- ^ "Prince Richard (Legend of Zelda)". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on February 12, 2011. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Nintendo Co., Ltd (December 1, 1998). The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening DX. Nintendo of America Inc.

Kid: Hey man! When you want to save, just push all the Buttons at once! ...Uh, don't ask me what that means, I'm just a kid!

- ^ "The Official Zelda Timeline, Now With Added Detail". Kotaku.com. December 27, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ Nintendo Co., Ltd (December 1, 1998). The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening DX. Nintendo of America Inc.

Marin: You must still be a little woozy. You are on Koholint Island!

- ^ Nintendo Co., Ltd (December 1, 1998). The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening DX. Nintendo of America Inc.

Marin: If I was a seagull, I would fly as far as I could! I would fly to far away places and sing for many people! ...If I wish to the Wind Fish, I wonder if my dream will come true...

- ^ Nintendo Co., Ltd (December 1, 1998). The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening DX. Nintendo of America Inc.

To the finder, the isle of Koholint is but an illusion... Human, monster, sea, sky... a scene on the lid of a sleeper's eye... Awake the dreamer, and Koholint will vanish much like a bubble on a needle... Cast-away, you should know the truth!

- ^ a b c d e The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening Instruction Booklet. Nintendo of America Inc. August 1993. pp. 9–28.

- ^ "Zelda Retrospective Part 6". GameTrailers. MTV Networks. November 20, 2006. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening – Nintendo Player's Guide. Nintendo of America Inc. 1994. p. 84.

- ^ "Strategy – Bosses of the Egg". Nintendo of America Inc. Archived from the original on February 24, 1998.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Nintendo Co., Ltd (December 1, 1998). The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening DX. Nintendo of America Inc.

Wind Fish: But, verily, it be the nature of dreams to end! When I dost awaken, Koholint will be gone...

- ^ "Link's Awakening – Frequently Asked Questions".

- ^ a b c Cleveland, Adam (September 17, 1999). "Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening DX – Game Boy Color Review". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- ^ Vestal, Andrew; O'Neill, Cliff; Shoemaker, Brad. "History of Zelda". GameSpot. CBS Interactive Inc. p. 13. Archived from the original on October 16, 2003. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e "「ゼルダの伝説 夢をみる島」開発スタッフ名鑑". Nintendo Official Guide Book – The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening (in Japanese). Shogakukan Inc. July 1993. pp. 120–124. ISBN 4-09-102448-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "開発スタッフアンケート". ゲームボーイ&ゲームボーイカラー 任天堂公式ガイドブック ゼルダの伝説 夢を見る島DX (in Japanese). Shogakukan Inc. February 20, 1999. pp. 108–111. ISBN 4-09-102679-6.

- ^ Kohler, Chris (December 4, 2007). "Interview: Super Mario Galaxy Director On Sneaking Stories Past Miyamoto". Wired: GameLife. Condé Nast Digital. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ "Interview: Nintendo's Unsung Star". Next Generation. Future US, Inc. February 6, 2008. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Iwata Asks: The History of Handheld The Legend of Zelda Games – Make All the Characters Suspicious Types". Nintendo of America Inc. January 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ Skrebels, Joe (February 19, 2014). "Monkey Men: talking to Michael Kelbaugh and Kensuke Tanabe". Official Nintendo Magazine. Nintendo. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ Nintendo Co., Ltd (December 1, 1998). The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening DX. Nintendo of America Inc. Scene: staff credits.

- ^ "Zelda Retrospective Part 1". GameTrailers. MTV Networks. October 13, 2006. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ ピアノソロ ゼルダの伝説シリーズ/スーパーベスト (in Japanese). Yamaha Music Media Corporation. May 26, 2010. Archived from the original on December 11, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Orchestral Game Music Concert 3 (Media notes). Sony Records. 1993.

- ^ "Smash Bros. Dojo!! – Full Song List with Secret Songs". Nintendo of America Inc. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

- ^ "GDC 2004: The History of Zelda". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. March 25, 2004. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ a b Williamson, Matt (August 20, 1993). "'Legend of Zelda' Still Growing". Rocky Mountain News. p. C1.

- ^ Bette, Harrison (August 30, 1993). "Riding the rails for Nintendo contest". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. p. B2.

- ^ "Mega Mirror; Win two Game Boy games". The Mirror. February 27, 1999. p. 41.

- ^ Musashi (February 7, 2000). "Reviews – The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening DX". RPGFan. Archived from the original on March 27, 2009. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- ^ Scullion, Chris (September 26, 2010). "3DS Virtual Console Will Play Game Boy Games". Official Nintendo Magazine. Future Publishing Limited. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ^ Goldfarb, Andrew (July 15, 2013). "2013 Club Nintendo Elite Status Rewards Now Available". IGN Entertainment, INC. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ a b "The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening for Game Boy". GameRankings. CBS Interactive Inc. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ a b "The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening DX for Game Boy Color". GameRankings. CBS Interactive Inc. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ Williamson, Colin. "Link's Awakening DX - Review". AllGame. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ^ a b Davis, Cameron (January 28, 2000). "The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening DX Review". GameSpot. CBS Interactive Inc. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Nester Awards Results". Nintendo Power. 1 (60). Nintendo of America Inc: 54–57. May 1994.

- ^ a b "NP Top 200". Nintendo Power. 1 (200). Nintendo of America Inc: 58–66. February 2006.

- ^ a b "Readers' Picks Top 100 Games: 31–40". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. 2006. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- ^ a b c "IGN Top 100 Games 2007 – 78. The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. December 9, 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Electronic Gaming Monthly's Buyer's Guide". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Ziff Davis Media Inc. January 1994.

- ^ Parish, Jeremy (November 15, 2006). "Link of A Thousand Faces". 1UP.com. UGO Entertainment, Inc. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ Reeves, Ben (June 24, 2011). "The 25 Best Game Boy Games Of All Time". Game Informer. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ a b Carter, Chip (August 4, 1993). "Nintendo Creates Legend That Fits in Your Hand". The Washington Post.

- ^ Joukiri, An (July 4, 2007). 「ゼルダの伝説 夢幻の砂時計」レビュー. ITmedia +D Games (in Japanese). ITmedia Inc. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ ゲームクエスト(ライブラリ) – ゼルダの伝説 夢をみる島. Mainichi.jp (in Japanese). Mainichi Newspapers Co. Ltd. February 25, 2005. Archived from the original on March 3, 2009. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ^ Diamond, John (December 19, 1993). "Little Plumber Boy; Night and Day". The Mail. p. 33.

- ^ Hughes, Gwyn (December 9, 1993). "The Guardian Features Page". The Guardian. p. 21.

- ^ a b Provick, Bill (August 4, 1994). "Nintendo's Game Boy on big screen". The Ottawa Citizen. p. J2 (Citizen Section: Weekend Fun; Electronic Gaming).

- ^ Burrill, William (October 14, 1993). "Plot is a bit cliched, but Rocket Knight game has big, bright graphics". The Gazette. p. E5.

- ^ Monk, Katherine (May 6, 1999). "Zelda lives up to her legend". The Vancouver Sun. p. F23.

- ^ Wilson, A. (January 14, 1999). "What's On; The Legend of Zelda DX". Courier Mail. p. 4.

- ^ Amjadali, Samantha; Scatena, Dino (May 20, 1999). "Game on". The Daily Telegraph. p. T6.

- ^ "Zelda: Link's Awakening DX". Total Games' Guide to the Game Boy Color (2). Paragon Publishing Ltd: 16. 1999.

- ^ Smith, David (October 20, 1993). "Video games master Nintendo forecasting a record sales year". The Vancouver Sun. p. D5.

- ^ Kelley, Malcom (November 19, 2000). "Fun time for couch potatoes: Video game reviews". National Post. p. F6.

- ^ Parton, Rob (March 31, 2004). "Japandemonium – Xenogears vs. Tetris". RPGamer. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ^ "Nintendo Power – The 20th Anniversary Issue!". Nintendo Power (231). Future Publishing Limited: 72. August 2008.

- ^ Gibson, Ellie (February 27, 2009). "Guinness lists top 50 games of all time". Eurogamer.net. Eurogamer Network Ltd. Retrieved May 17, 2009.

- Notes

External links