François Mauriac

François Mauriac | |

|---|---|

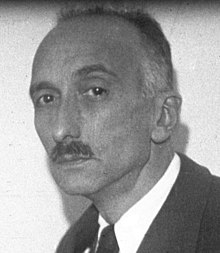

Mauriac in 1933 | |

| Born | François Charles Mauriac 11 October 1885 Bordeaux, Gironde, France |

| Died | 1 September 1970 (aged 84) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Novelist, dramatist, critic, poet, journalist |

| Education | University of Bordeaux (1905) École des Chartes |

| Notable awards | Grand Prix du roman de l'Académie française 1926 Nobel Prize in Literature 1952 |

| Relatives | Anne Wiazemsky (granddaughter) |

| Signature | |

François Charles Mauriac (French: [fʁɑ̃swa ʃaʁl moʁjak]; Occitan: Francés Carles Mauriac; 11 October 1885 – 1 September 1970) was a French novelist, dramatist, critic, poet, and journalist, a member of the Académie française (from 1933), and laureate of the Nobel Prize in Literature (1952). He was awarded the Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur in 1958.

Biography

[edit]François Charles Mauriac was born in Bordeaux, France. He studied literature at the University of Bordeaux, graduating in 1905, after which he moved to Paris to prepare for postgraduate study at the École des Chartes.

On 1 June 1933, he was elected a member of the Académie française, succeeding Eugène Brieux.[1]

A former Action française supporter, he turned to the left during the Spanish Civil War, criticizing the Catholic Church for its support of Franco. After the fall of France to the Axis during the Second World War, he briefly supported the collaborationist régime of Marshal Pétain, but joined the Resistance as early as December 1941. He was the only member of the Académie française to publish a Resistance text with the Editions de Minuit.

Mauriac had a bitter dispute with Albert Camus immediately following the Liberation of France. At that time, Camus edited the Resistance paper Combat (thereafter an overt daily, until 1947), while Mauriac wrote a column for Le Figaro. Camus said newly liberated France should purge all Nazi collaborator elements, but Mauriac warned that such disputes should be set aside in the interests of national reconciliation. Mauriac also doubted that justice would be impartial or dispassionate, given the emotional turmoil of the Liberation. Despite having been viciously criticised by Robert Brasillach, he campaigned against his execution.

Mauriac also had a bitter public dispute with Roger Peyrefitte, who criticised the Vatican in books such as Les Clés de saint Pierre (1953). Mauriac threatened to resign from the paper he was working with at the time (L'Express) if they did not stop carrying advertisements for Peyrefitte's books. The quarrel was exacerbated by the release of the film adaptation of Peyrefitte's Les Amitiés Particulières, and culminated in a virulent open letter by Peyrefitte in which he accused Mauriac of homosexual tendencies and called him a Tartuffe, hypocrite.[2]

Mauriac was opposed to French rule in Vietnam, and strongly condemned the use of torture by the French army in Algeria.

In 1952, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature "for the deep spiritual insight and the artistic intensity with which he has in his novels penetrated the drama of human life".[3] He was awarded the Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur in 1958.[4] He published a series of personal memoirs and a biography of Charles de Gaulle. Mauriac's complete works were published in twelve volumes between 1950 and 1956. He encouraged Elie Wiesel to write about his experiences as a Jewish teenager during the Holocaust, and wrote the foreword to Elie Wiesel's book Night.

He was the father of writer Claude Mauriac and grandfather of Anne Wiazemsky, a French actress and author who worked with and married French director Jean-Luc Godard.

François Mauriac died in Paris on 1 September 1970, and was interred in the Cimetière de Vemars, Val d'Oise, France.

Awards and honours

[edit]- 1926 — Grand Prix du roman de l'Académie française

- 1933 — Member of the Académie française

- 1952 — Nobel Prize in Literature

- 1958 — Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur

Works

[edit]Novels, novellas and short stories

[edit]- 1913 – L'Enfant chargé de chaînes («Young Man in Chains», tr. 1961)

- 1914 – La Robe prétexte («The Stuff of Youth», tr. 1960)

- 1920 – La Chair et le Sang («Flesh and Blood», tr. 1954)

- 1921 – Préséances («Questions of Precedence», tr. 1958)

- 1922 – Le Baiser au lépreux («The Kiss to the Leper», tr. 1923 / «A Kiss to the Leper», tr. 1950)

- 1923 – Le Fleuve de feu («The River of Fire», tr. 1954)

- 1923 – Génitrix («Genetrix», tr. 1950)

- 1923 – Le Mal («The Enemy», tr. 1949)

- 1925 – Le Désert de l'amour («The Desert of Love», tr. 1949) (Awarded the Grand Prix du roman de l'Académie française, 1926.)

- 1927 – Thérèse Desqueyroux («Thérèse», tr. 1928 / «Thérèse Desqueyroux», tr. 1947 and 2005)

- 1928 – Destins («Destinies», tr. 1929 / «Lines of Life», tr. 1957)

- 1929 – Trois Récits A volume of three stories: Coups de couteau, 1926; Un homme de lettres, 1926; Le Démon de la connaissance, 1928

- 1930 – Ce qui était perdu («Suspicion», tr. 1931 / «That Which Was Lost», tr. 1951)

- 1932 – Le Nœud de vipères («Vipers' Tangle», tr. 1933 / «The Knot of Vipers», tr. 1951)

- 1933 – Le Mystère Frontenac («The Frontenac Mystery», tr. 1951 / «The Frontenacs», tr. 1961)

- 1935 – La Fin de la nuit («The End of the Night», tr. 1947)

- 1936 – Les Anges noirs («The Dark Angels», tr. 1951 / «The Mask of Innocence», tr. 1953)

- 1938 – Plongées A volume of five stories: Thérèse chez le docteur, 1933 («Thérèse and the Doctor», tr. 1947); Thérèse à l'hôtel, 1933 («Thérèse at the Hotel», tr. 1947); Le Rang; Insomnie; Conte de Noël.

- 1939 – Les Chemins de la mer («The Unknown Sea», tr. 1948)

- 1941 – La Pharisienne («A Woman of Pharisees», tr. 1946)

- 1951 – Le Sagouin («The Weakling», tr. 1952 / «The Little Misery», tr. 1952) (A novella)

- 1952 – Galigaï («The Loved and the Unloved», tr. 1953)

- 1954 – L'Agneau («The Lamb», tr. 1955)

- 1969 – Un adolescent d'autrefois («Maltaverne», tr. 1970)

- 1972 – Maltaverne (the unfinished sequel to the previous novel; posthumously published)

Plays

[edit]- 1938 – Asmodée («Asmodée; or, The Intruder», tr. 1939 / «Asmodée: A Drama in Three Acts», tr. 1957)

- 1945 – Les Mal Aimés

- 1948 – Passage du malin

- 1951 – Le Feu sur terre

Poetry

[edit]- 1909 – Les Mains jointes

- 1911 – L'Adieu à l'Adolescence

- 1925 – Orages

- 1940 – Le Sang d'Atys

Memoirs

[edit]- 1931 – Holy Thursday: an Intimate Remembrance

- 1960 – Mémoires intérieurs

- 1962 – Ce Que Je Crois

- 1964 – Soirée Tu Danse[clarification needed]

Biography

[edit]- 1937 – Life of Jesus

- 1964 - De Gaulle de François Mauriac (French edition), 1966 English -(Doubleday)

Essays and criticism

[edit]- 1919 – Petits Essais de Psychologie Religieuse: De quelques coeurs inquiets. Paris: Societe litteraire de France. 1919.

- 1936 - “God and Mammon” in ‘Essays in Order: New Series, No. 1’. Edited by Christopher Dawson and Bernard Wall. Published in London by Sheed & Ward

- 1961 – Second Thoughts: Reflections on literature and on Life (tr. by Adrienne Foulke). Darwen Finlayson

- François Mauriac on Race, War, Politics, and Religion: The Great War Through the 1960s. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. 2016. ISBN 978-0-8132-2789-4. Edited and translated by Nathan Bracher.

Further reading

[edit]- Scott, Malcolm (1980), Mauriac: The Politics of a Novelist, Scottish Academic Press, ISBN 9780707302621

- Dudley Edwards, Owen (1982), review of Mauriac: The Politics of a Novelist by Malcolm Scott, in Murray, Glen (ed.), Cencrastus No. 8, Spring 1982, pp. 46 & 47, ISSN 0264-0856

- Mauriac, Caroline (1981), François Mauriac: Lettres d'une vie (1904–1969), Bernard Grasset, Paris

See also

[edit]

References

[edit]- ^ Cf. Académie française, Les immortels: François Mauriac (1885–1970) Archived 2008-09-20 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- ^ Sibalis, Michael D. (2006). "Peyrefitte, Roger". glbtq.com. Archived from the original on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- ^ Cf. The Nobel Foundation, The Nobel Prize in Literature 1952: François Mauriac (in English)

- ^ Cf. Académie française, Les immortels: François Mauriac (1885–1970) Archived 2008-09-20 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

External links

[edit]- Works by or about François Mauriac at the Internet Archive

- Le site littéraire François Mauriac Archived 2013-06-20 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- The François Mauriac Centre at Malagar (Saint-Maixant, Gironde) (in French)

- Université McGill: le roman selon les romanciers Archived 2014-05-02 at the Wayback Machine (in French)Inventory and analysis of François Mauriac's non-noveltistic writing

- Jean le Marchand & John P.C. Train (Summer 1953). "Interviews: François Mauriac, The Art of Fiction No. 2". The Paris Review. No. 2. pp. 1–15. (in English)

- François Mauriac on Nobelprize.org

- 1885 births

- 1970 deaths

- Writers from Bordeaux

- French Roman Catholic writers

- 20th-century French novelists

- 20th-century French dramatists and playwrights

- French literary critics

- French male novelists

- Members of the Académie Française

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- French Nobel laureates

- Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

- Grand Prix du roman de l'Académie française winners

- 20th-century French journalists

- Christian novelists

- Christian humanists

- Le Figaro people