Yaho (archeological site)

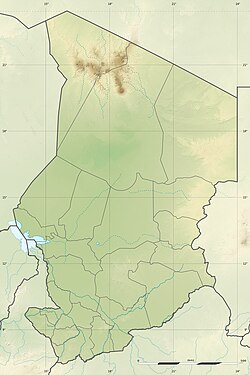

| Location | Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Region, |

|---|---|

| Region | North-Central Africa |

| Coordinates | 17°40′01″N 17°19′59″E / 17.667°N 17.333°E |

| Type | Archaeological |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1961 |

| Archaeologists | Yves Coppens |

Yaho or Yayo[1] is an archeological site 160 kilometers northwest of Koro Toro, Chad. In 1961, Yves Coppens excavated a partial hominin face and erected the taxon Tchadanthropus uxoris.[2] Loxodonta atlantica were also discovered from the site.[3]

Chronology

[edit]It is proposed that the middle of the Angamma delta bore Holocene strata dating to 1000 years in the lowest parts and up to 7300 years at the latest. Other parts of the formation reach up to 10,000 years.[4]

Geology

[edit]

The Angamma Delta is found within the area north of paleolake Megachad. The delta is very well preserved, standing up to 330m tall, as it can be observed sloping into a mudstone and diatomite-filled basin that drops 240m. The delta was fed by a braided fluvial distributary leading from the Tibesti Mountains from the north. They do not cut through the delta, suggesting that the braided rivers dried before the lake did. Delta sediment was visibly disturbed by waves from the lake, and the front was eroded, revealing other sediments within.[4]

Its sediments are very exposed through a series of cliffs and canyons that run perpendicular from the delta. Underneath the delta are volcanic tuffs and breccias overlain with diatomite. The sediment is composed of silts and fine sand interspersed with thin intraformational conglomerates. Strata thicken nearer to the top and have distinct boundaries. It shows evidence of river flooding events that supplied sediment to the delta.[4]

Tchadanthropus uxoris

[edit]Discovery and Dating

[edit]On March 16, 1961, Yves Coppens' wife, Françoise Le Guennec,[5] discovered a hominin fossil at one end of the Angamma cliff, 11 kilometers from the western well of Yayo. Initially, the specimen was assumed to be an australopithecine, but Coppens would later assign it the temporary name Tchadanthropus uxoris[6] based on the country and lake of origin and honoring Le Guennec. The hominin fossil was found in deposits that were also populated with fossils of the proboscid Loxodonta atlantica, which Coppens suggested might place the hominin within the late Lower or early Middle Pleistocene.[3]

In 1965, Marcel Bleustein organized a conference for the discovery, which scientists were very skeptical of. The press, however, were more interested in the implications of the discovery.[7] The discovery of this fossil made Coppens media famous.[8] Tobias (1973) stated that the fossil was likely to be Homo erectus and less than one million years old.[9] In 2010, the specimen was given an updated age estimate of 900-700 kya.[10] According to data proposed by Servant (1983), the specimen may be only 10 ka based on the geology of the site.[11]

Description

[edit]The specimen may be a young individual based on the presence of a metopic suture, but this feature was also present in the adult[12] Zhoukoudian XII, so it may be a feature present regardless of age. The face is broad and short, but due to erosion of the upper jaw, its entire height cannot be calculated. The vault is high and intermediate in curvature between Zhoukoudian, Chellean Man, and Australopithecus. Another possible testament to age is slight postorbital constriction. However, the frontal sinus is expanded, indicative of adulthood. The tori are heavier than those of australopiths, but lighter than later hominins. The frontal process bears a posterior obliquity that might signify a high zygomatic root. The sockets are large and rectangular like those of Kabwe. There is substantial prognathism below the nose; however, Wood (2002) notes that this apparent prognathism may be a product of warping caused by winds that inadvertently gave the skull an australopithecine-like appearance, which would support Servant (1983)'s hypothesis that the specimen is only 10 ka old.[13][11] No teeth were preserved, but the incisor socket suggests that the teeth were small, with no diastema. The nasal anatomy is similar to that of Solo.[3] The brain capacity is difficult to calculate, but it may have been on the smaller end.[14]

Classification

[edit]Originally, Coppens provisionally correlated the fossil as an australopithecine. In 1966, he suggested that the face bore similarities with early and later hominins, thinking that it either represented a late australopithecine or, more likely in his opinion, an early "pithecanthropine". He also considered attribution to Homo habilis, which was a recent advancement at the time.[6] He assigned the provisional name Tchadanthropus uxoris to the find as a placeholder until greater understanding of human evolution could allow for taxonomic simplification.[3] In 2017, Coppens admitted in an interview that the fossil was closer to H. erectus than an australopithecine.[7] A less popular scientific name for the specimen is Homo uxoris.[10] Most regard the specimen as a member of H. habilis or H. erectus.[15][16]

Fauna

[edit]Ostracods

[edit]| Species | Locality | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heterocypris giesbrechtii | CH38 | Abundant, all life stages | [4] |

| Sarscypridopsis aculeata | One specimen | ||

| Sarscypridopsis cf. bicornis | CH39 | ||

| Darwinula stevensoni | Moderately abundant | ||

| Cytheridella cf. tepida |

Molluscs

[edit]| Species | Locality | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| "Two gastropod species" | CHG59 | [4] | |

| Coelatura aegyptiaca | CHG59, CH60 | Bivalve | |

| Pisidium sp. | |||

| Valvata sp. |

Arthropods

[edit]| Species | Locality | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candona cf. neglecta | Possibly a new species of crustacean | [4] | |

| Limnocythere inopinata | CH60 | Moderately abundant crustacean |

Mammals

[edit]| Species | Locality | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homo erectus | 11km west of the Angamma cliff | One hominin face discovered by Françoise Le Guennec,[5] wife of Yves Coppens and variously attributed to various species of hominin. Its true placement is unknown. | [3] |

| Homo habilis | |||

| Homo uxoris | |||

| Tchadanthropus uxoris | |||

| Loxodonta africana[4] | |||

| Loxodonta atlantica | An elephant found in association with hominin remains | ||

| "hippopotamus" | "A small form," no genus mentioned |

References

[edit]- ^ "YAYO Geography Population Map cities coordinates location - Tageo.com". www.tageo.com. Retrieved 2024-01-28.

- ^ Whitehouse, Ruth D., ed. (1983). "The Macmillan Dictionary of Archaeology". SpringerLink. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-04874-8. ISBN 978-1-349-04876-2.

- ^ a b c d e "An Early Hominid From Chad". Current Anthropology. 7 (5): 584–585. 1966. doi:10.1086/200776. ISSN 0011-3204. S2CID 143549941.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bristow, Charlie S.; Holmes, Jonathan A.; Mattey, Dave; Salzmann, Ulrich; Sloane, Hilary J. (2018-12-01). "A late Holocene palaeoenvironmental 'snapshot' of the Angamma Delta, Lake Megachad at the end of the African Humid Period". Quaternary Science Reviews. 202: 182–196. Bibcode:2018QSRv..202..182B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.04.025. ISSN 0277-3791. S2CID 135254848.

- ^ a b Pitts, Mike (2022-07-04). "Yves Coppens obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-01-28.

- ^ a b texte, Académie des sciences (France) Auteur du (1965-03-01). "Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des sciences / publiés... par MM. les secrétaires perpétuels". Gallica. Retrieved 2024-01-28.

- ^ a b Coppens, Yves (2017). "L'histoire de l'humanité racontée par les fossiles". Pourlascience.fr (in French). Retrieved 2024-01-28.

- ^ "Yves Coppens, codécouvreur de Lucy et visage de la paléontologie française, est mort". Le Monde.fr (in French). 2022-06-22. Retrieved 2024-01-28.

- ^ Tobias, Phillip V. (1973). "New Developments in Hominid Paleontology in South and East Africa". Annual Review of Anthropology. 2: 311–334. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.02.100173.001523. ISSN 0084-6570. JSTOR 2949274.

- ^ a b Birx, H. James (2010-06-10). 21st Century Anthropology: A Reference Handbook. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-5738-0.

- ^ a b Servant, Michel (1983). Séquences continentales et variations climatiques: évolution du bassin du Tchad au Cénozoïque supérieur (in French). ORSTOM. ISBN 978-2-7099-0679-1.

- ^ Boaz, Noel T.; Ciochon, Russell L.; Xu, Qinqi; Liu, Jinyi (2004-05-01). "Mapping and taphonomic analysis of the Homo erectus loci at Locality 1 Zhoukoudian, China". Journal of Human Evolution. 46 (5): 519–549. Bibcode:2004JHumE..46..519B. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.01.007. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 15120264.

- ^ Wood, Bernard (2002). "Hominid revelations from Chad". Nature. 418 (6894): 133–135. doi:10.1038/418133a. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 12110870.

- ^ Yves Coppens : le Tchadanthropus uxoris | INA (in French), retrieved 2024-01-28

- ^ Cornevin, Robert (1967). Histoire de l'Afrique (in French). Payot. ISBN 978-2-228-11470-7.

- ^ "Adventures in the Bone Trade". SpringerLink. 2001. doi:10.1007/b97349. ISBN 0-387-98742-8.