Notholithocarpus

| Notholithocarpus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Foliage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Fagaceae |

| Subfamily: | Quercoideae |

| Genus: | Notholithocarpus Manos, Cannon & S.H.Oh |

| Species: | N. densiflorus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Notholithocarpus densiflorus | |

| |

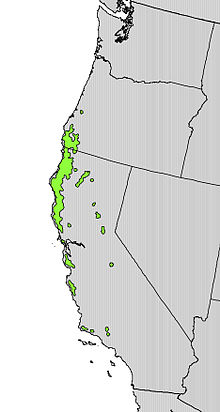

| Notholithocarpus densiflorus range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Notholithocarpus densiflorus, commonly known as the tanoak or tanbark-oak, is a broadleaf tree in the family Fagaceae, and the type species of the genus Notholithocarpus. It is a hardwood tree that is native to the far western United States, particularly Oregon and California. It ranges from 15–40 meters (49–131 feet) in height, with a trunk diameter of 60–190 centimeters (24–75 inches). There are a number of radical and incompatible perceptions of tanoak, it has been seen as a cash crop to treasured food plant to trash tree.[2]

Description

[edit]It can reach 40 meters (130 feet) tall in the California Coast Ranges, though 15–25 m (49–82 ft) is more usual,[3] and can have a trunk diameter of 60–190 centimeters (24–75 inches). The bark is fissured, and ranges from gray to brown.[3] The tree's average age appears to be 180 years, although some estimates reach as high as 300 to 400 years old.[4]

The leaves are alternate, 8–13 cm (3–5 in), with toothed margins and a hard, leathery texture.[3] At first they are covered in dense orange-brown scurfy hairs on both sides, which wear off over time, more slowly on the underside of the leaf. The leaves will persist for three to four years.

Flowers are unisexual, as is typical for members of the Beech Family (Fagaceae). The tree can flower during any season except winter, but typically blossoms appear in June, July, or August with coastal and low-elevation trees blooming the earliest. The small, solitary female flowers aggregate as the base of the erect male catkin, each subtended by a small bract. The flowers are wind or insect pollinated.[5]

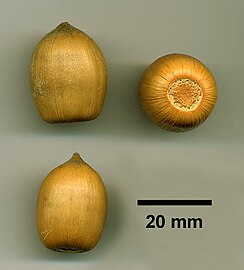

The seed is an acorn 2–3.5 cm (3⁄4–1+1⁄2 in) long[6] and 2 cm in diameter, very similar to an oak acorn, but with a very hard, woody nut shell more like a hazel nut. The nut sits in a cup during its 18-month maturation; the outside surface of the cup is rough with short spines.[3] The nuts are produced in clusters of a few together on a single stem. Tanoak acorns have distinguishing caps that are hairy, rather then scaly.[7]

Currently, the largest known tanoak specimen is on private timberland near the town of Ophir, Oregon. It has a circumference of 7.9 m (26 ft), is about 2.51 m (8 ft 3 in) in diameter at breast height, and is 37 m (121 ft) tall with an average crown spread of 17 m (56 ft).[8]

Notholithocarpus densiflorus var. echinoides

[edit]This is a variant species resulting from a mutation, it is a shrub-like form of Tanoak.[5] Members of populations in interior California (in the northern Sierra Nevada) and the Klamath Mountains in southwest Oregon are smaller, rarely exceeding 3 m (9 ft 10 in) in height and often shrubby, with smaller leaves, 4–7 cm (1+1⁄2–2+3⁄4 in) long; these are separated as "dwarf tanoak", Notholithocarpus densiflorus var. echinoides. The variety intergrades with the type in northwest California and southwest Oregon. Tanoak grows as a shrub on serpentine soils. This mutant is used in horticulture, due in part to its rarity.[5]

Similar species

[edit]Chrysolepis chrysophylla is similar, but the leafs are scaly underneath and the fruits are spiny.[6]

Taxonomy

[edit]By 2008, the species was moved into a new genus, Notholithocarpus (from Lithocarpus), based on multiple lines of evidence.[9] It is most closely related to the north temperate oaks (Quercus) and not as closely related to the Asian tropical stone oaks (Lithocarpus, where it was previously placed), but instead is an example of convergent morphological evolution.

While related to oaks (as well as chestnuts), the name is written as 'tanoak' because it is not a true oak.[3]

Distribution

[edit]It is native to the far western United States, found in southwest Oregon and in California as far south as the Transverse Ranges and east in the Sierra Nevada. It grows from sea level to elevations of 1,200 m (3,900 ft).[3]

The tree grows from near Santa Barbara, California, to just north of the Umpqua River of Southwestern Oregon. Inland, populations occur in patches throughout the Siskiyou Mountains and the southern tip of the Cascade Range to the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains southwest of Yosemite Valley.[4]

Ecology

[edit]Tanoak is shade tolerant and benefits from disturbances. It is susceptible to wildfire and wounds that are exploited by rot fungi.[3] It is one of the species most seriously affected by the disease "sudden oak death" (Phytophthora ramorum), with high mortality reported over much of the species' range.[10]

Fine hairs on the young leaves and twigs discourage deer from eating them.[3] Various wildlife species depend on the large, oil-rich nuts for fattening up for the winter, including: band-tailed pigeons, squirrels, deer, elk, and bears.[3][4]

Tanoaks reduce erosion through their interwoven network of roots that quickly become established after disturbances, like logging. The leaf litter of tanoak moderates soil temperature, restores soil texture, and increases microbial activity including nitrogen-fixing bacteria that improve soil fertility damaged by disturbance. Its deep roots move subsoil nutrients closer to the surface where the shallower rooted conifers can access them.[4]

Additionally, tanoak helps reduce threats to economically important conifers. Douglas-fir is impeded by laminated root rot, which tanoak and other hardwoods are immune to; through periods of tanoak dominance in the forest, disease problems of softwoods are reduced.[4]

Pests and diseases

[edit]Sudden oak death, or Phytophthora ramorum, was first noticed as a killer of tanoaks in the mid 1990s. The horticultural trade accidentally introduced P. ramorum to North America and the pathogen spread quickly from Marin County and Santa Cruz Mountains. This disease has killed millions of tanoaks and it continues to spread despite the efforts of landowners, scientists, and government agencies. Currently, no cure exists for infected trees, and thus far tanoak exhibits little genetic resistance to the exotic water mold that causes the disease. Fortunately, large areas with extensive tanoak stands remain uninfected.[5]

Conservation

[edit]There are many collaborative responses to the current tanoak crisis. Fire safe councils are formed to help reduce fuel for wildfires and the competition conifers present to prairie-oak ecosystems. Additionally, there are various methods being utilized to monitor for P. ramorum. There are also contemporary efforts by indigenous peoples to reestablish traditional burning practices in an effort to enable the growth of prairie-oak landscapes and promote tanoaks.[4]

Uses

[edit]Culinary

[edit]The nut kernel is very bitter[6] and is inedible for people without leaching. However, with minimal processing, its acorns yield a sweet, nutty meal rich in complex carbohydrates and nutritious fats. Compared to grains like wheat, tanoak acorns are low in protein but superior in caloric value due to the high amount of nutritious fats they contain. Additionally, the acorns are soft enough to chew without processing, but the tannic acid they contain must be removed to make them useful as human food. Compared to most acorns, tanoak nutmeats are significantly larger, making them easier to process.[5] Some California Native Americans prefer this nut to those of many oak acorns because it stores well due to the comparatively high tannin content.

The Concow tribe call the nut hä’-hä (Konkow language).[11] The Hupa people use the acorns to make meal, from which they would make mush, bread, biscuits, pancakes, and cakes. They also roast the acorns and eat them.[12] Roasted, the seeds can be used as a coffee substitute.[13] Samuel Thayer reports that despite their bitterness they are easy to dry, grind, and leach and produce a better-tasting flour than do acorns of oaks in the Quercus genus that he has processed.[14]

Tanning

[edit]The name tanoak refers to its tannin-rich bark, a type of tanbark, used in the past for tanning leather before the use of modern synthetic tannins. Tanoak bark enabled a lucrative American tanning industry on the Pacific Coast between the 1840s and the 1920s. The high concentration of tannins in the bark of tanoak enabled tanneries to produce heavy leathers, which were used to make items such as saddles, bridles, and luggage, which were in high demand.[4] By 1907, the use of tanoak for tannin was subsiding due to the scarcity of large tanoak trees. Despite years of warnings about overharvesting, the tanning industry depleted tanoaks and there were not enough trees around for a worthwhile economic return. By the early 1960s, there were only a few natural tannin operations left in California. The industry was beginning to switch to a synthetic alternative.[15]

Timber

[edit]The wood is strong and sometimes used as lumber, but suitable trees are usually inaccessible. Tanoak also generates wood that is useful for flooring and cabinetry, but it is less profitable to harvest than conifers and is more difficult to process.[4] It is also used as firewood.[3]

Other

[edit]A mulch made from the leaves of the tanoak can repel grubs and slugs.[13] Tanoak was traditionally used by indigenous communities in the making of fishing nets, baskets, and medicines, as well as dyes. Tanoak was also utilized medicinally in Indigenous communities, the acorns were used as cough drops and a bark decoction was used to treat facial sores and loose teeth.[5] The tree's tannins have been used as an astringent.[16]

In culture

[edit]Tanoak acorns have been a staple food for many indigenous peoples and formed the basis of a California acorn economy for thousands of years prior to white settlement. Though indigenous peoples gathered and favored acorns from multiple oak species, northwestern tribes in particular often preferred tanoak when obtainable. Multiple characteristics of the acorns contributed to tanoak’s popularity as a staple food, including: a thick shell that is more resistant to fungal and insect attacks; the acorns longevity in storage; tanoak's reliability as a producer; and tanoak acorns high caloric value due to the high amount of nutritious fats they contain.[5]

Indigenous people have manipulated vegetation on a large-scale with fire management to favor tanoak acorn production. Frequent low-intensity burns set after the initial acorn drop killed the larvae inside as well as any already in leaf litter, which reduced the insect populations. The regular burnings also reduced the risk of catastrophic wildfires that would destroy the trees that produced their staple plant food. However, fire suppression after white settlement has caused conifers to invade prairie-oak mosaic vegetation and decrease the range and diversity of these ecosystems.[4]

Acorns in Europe were largely considered pig food and their high fat and carbohydrate content made them ideal for fattening up pigs before slaughtering. This formed a bias in Europeans that acorns were livestock fodder and not fit for human consumption. Beginning with American settlement, tanoak groves were repurposed to produce salted meats for cities and mining camps through the fattening of pigs on acorns.[4]

State Foresters ranked tanoak among the most abused tree species in their first biennial report in 1885-1886. The harvests of tanoak bark created lots of wood waste, and clear cutting development only worsened conditions. The common hardwood tree later became the target of eradication campaigns involving herbicides in the mid-1900s. This was due to a promotion of softwoods, or conifers, for industrial uses.

Today, many indigenous people still favor tanoak acorns as an important food. Traditional dishes made with the acorns are still served at tribal gatherings and celebrations, and as a healing food for the sick and elderly.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ Stritch, L. (2018). "Notholithocarpus densiflorus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T62005598A62005616. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-1.RLTS.T62005598A62005616.en. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ Bowcutt, Frederica (2015). The Tanoak Tree: An Environmental History of a Pacific Coast Hardwood. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295742724.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Arno, Stephen F.; Hammerly, Ramona P. (2020) [1977]. Northwest Trees: Identifying & Understanding the Region's Native Trees (field guide ed.). Seattle: Mountaineers Books. pp. 225–229. ISBN 978-1-68051-329-5. OCLC 1141235469.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bowcutt, Frederica (2011). "Tanoak Target: The Rise and Fall of Herbicide Use on a Common Native Tree". Environmental History. 16 (2): 197–225. ISSN 1084-5453.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bowcutt, Frederica S; Bowcutt, Frederica S. (2013). "Tanoak Landscapes: Tending a Native American Nut Tree". Madroño; a West American journal of botany. 60: 64––86. doi:10.3120/0024-9637-60.2.64.

- ^ a b c Turner, Mark; Kuhlmann, Ellen (2014). Trees & Shrubs of the Pacific Northwest (1st ed.). Portland, OR: Timber Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-1-60469-263-1.

- ^ "Tanoak Genus: Common Trees of the Pacific Northwest". treespnw.forestry.oregonstate.edu. Retrieved December 21, 2024.

- ^ "Tanoak Lithocarpus densiflorus". American Forests. Archived from the original on December 13, 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Manos, Paul S.; Cannon, Charles H.; Oh, Sang-Hun (2008). "Phylogenetic relationships and taxonomic status of the paleoendemic Fagaceae of Western North America: recognition of a new genus, Notholithocarpus" (PDF). Madroño. 55 (3): 181–190. doi:10.3120/0024-9637-55.3.181. S2CID 85671229. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 20, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ http://cisr.ucr.edu/sudden_oak_death.html Sudden Oak Death at University of California, Riverside, Center for Invasive Species Research

- ^ Chesnut, Victor King (1902). Plants used by the Indians of Mendocino County, California. Government Printing Office. p. 405. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ Merriam, C. Hart 1966 Ethnographic Notes on California Indian Tribes. University of California Archaeological Research Facility, Berkeley (p. 200)

- ^ a b Natural Medicinal Herbs: Reference page = Herb latin name: Lithocarpus pachyphylla

- ^ Thayer, Samuel (2010). Nature's Garden. Forager's Harvest Press. pp. 162, 165.

- ^ University of California Oak Woodland Management: Home Url = ucanr.edu Reference page = Does It Make Cents to Process Tanoak to Lumber

- ^ Tappeiner, John C.; McDonald, Philip M.; Roy, Douglass F. (1990). "Lithocarpus densiflorus". In Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H. (eds.). Hardwoods. Silvics of North America. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: United States Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) – via Southern Research Station.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Notholithocarpus densiflorus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Notholithocarpus densiflorus at Wikimedia Commons