Pig

| Pig | |

|---|---|

| |

| Domestic pigs | |

Domesticated

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Suidae |

| Genus: | Sus |

| Species: | S. domesticus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Sus domesticus Erxleben, 1777

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

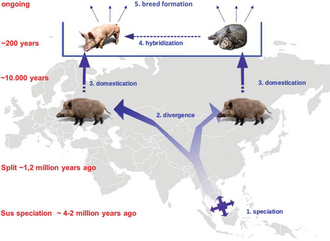

The pig (Sus domesticus), also called swine (pl.: swine) or hog, is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is named the domestic pig when distinguishing it from other members of the genus Sus. It is considered a subspecies of Sus scrofa (the wild boar or Eurasian boar) by some authorities, but as a distinct species by others. Pigs were domesticated in the Neolithic, both in East Asia and in the Near East. When domesticated pigs arrived in Europe, they extensively interbred with wild boar but retained their domesticated features.

Pigs are farmed primarily for meat, called pork. The animal's skin or hide is used for leather. China is the world's largest pork producer, followed by the European Union and then the United States. Around 1.5 billion pigs are raised each year, producing some 120 million tonnes of meat, often cured as bacon. Some are kept as pets.

Pigs have featured in human culture since Neolithic times, appearing in art and literature for children and adults, and celebrated in cities such as Bologna for their meat products.

Description

The pig has a large head, with a long snout strengthened by a special prenasal bone and a disk of cartilage at the tip.[2] The snout is used to dig into the soil to find food and is an acute sense organ. The dental formula of adult pigs is 3.1.4.33.1.4.3, giving a total of 44 teeth. The rear teeth are adapted for crushing. In males, the canine teeth can form tusks, which grow continuously and are sharpened by grinding against each other.[2] There are four hoofed toes on each foot; the two larger central toes bear most of the weight, while the outer two are also used in soft ground.[3] Most pigs have rather sparsely bristled hair on their skin, though there are some woolly-coated breeds such as the Mangalitsa.[4] Adult pigs generally weigh between 140 and 300 kg (310 and 660 lb), though some breeds can exceed this range. Exceptionally, a pig called Big Bill weighed 1,157 kg (2,551 lb) and had a shoulder height of 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in).[5]

Pigs possess both apocrine and eccrine sweat glands, although the latter are limited to the snout.[6] Pigs, like other "hairless" mammals such as elephants, do not use thermal sweat glands in cooling.[7] Pigs are less able than many other mammals to dissipate heat from wet mucous membranes in the mouth by panting. Their thermoneutral zone is 16–22 °C (61–72 °F).[8] At higher temperatures, pigs lose heat by wallowing in mud or water via evaporative cooling, although it has been suggested that wallowing may serve other functions, such as protection from sunburn, ecto-parasite control, and scent-marking.[9] Pigs are among four mammalian species with mutations in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor that protect against snake venom. Mongooses, honey badgers, hedgehogs, and pigs all have different modifications to the receptor pocket which prevents α-neurotoxin from binding.[10] Pigs have small lungs for their body size, and are thus more susceptible than other domesticated animals to fatal bronchitis and pneumonia.[11] The genome of the pig has been sequenced; it contains about 22,342 protein-coding genes.[12][13][14]

-

Skeleton

-

Skull

-

Bones of the foot

Evolution

Phylogeny

Domestic pigs are related to other pig species as shown in the cladogram, based on phylogenetic analysis using mitochondrial DNA.[15]

Taxonomy

The pig is most often considered to be a subspecies of the wild boar, which was given the name Sus scrofa by Carl Linnaeus in 1758; following from this, the formal name of the pig is Sus scrofa domesticus.[16][17] However, in 1777, Johann Christian Polycarp Erxleben classified the pig as a separate species from the wild boar. He gave it the name Sus domesticus, still used by some taxonomists.[18] The American Society of Mammalogists considers it a separate species.[19]

Domestication in the Neolithic

Archaeological evidence shows that pigs were domesticated from wild boar in the Near East in or around the Tigris Basin,[21] being managed in a semi-wild state much as they are managed by some modern New Guineans.[22] There were pigs in Cyprus more than 11,400 years ago, introduced from the mainland, implying domestication in the adjacent mainland by then.[23] Pigs were separately domesticated in China, starting some 8,000 years ago.[24][25][26] In the Near East, pig husbandry spread for the next few millennia. It reduced gradually during the Bronze Age, as rural populations instead focused on commodity-producing livestock, but it was sustained in cities.[27]

Domestication did not involve reproductive isolation with population bottlenecks. Western Asian pigs were introduced into Europe, where they crossed with wild boar. There appears to have been interbreeding with a now extinct ghost population of wild pigs during the Pleistocene. The genomes of domestic pigs show strong selection for genes affecting behavior and morphology. Human selection for domestic traits likely counteracted the homogenizing effect of gene flow from wild boars and created domestication islands in the genome.[28][29] Pigs arrived in Europe from the Near East at least 8,500 years ago. Over the next 3,000 years they interbred with European wild boar until their genome showed less than 5% Near Eastern ancestry, yet retained their domesticated features.[30]

DNA evidence from subfossil remains of teeth and jawbones of Neolithic pigs shows that the first domestic pigs in Europe were brought from the Near East. This stimulated the domestication of local European wild boar, resulting in a third domestication event with the Near Eastern genes dying out in European pig stock. More recently there have been complex exchanges, with European domesticated lines being exported, in turn, to the ancient Near East.[31][32] Historical records indicate that Asian pigs were again introduced into Europe during the 18th and early 19th centuries.[25]

History

Columbian Exchange

Among the animals that the Spanish introduced to the Chiloé Archipelago in the 16th century Columbian Exchange, pigs were the most successful in adapting to local conditions. The pigs benefited from abundant shellfish and algae exposed by the large tides of the archipelago.[33] Pigs were brought to southeastern North America from Europe by de Soto and other early Spanish explorers. Escaped pigs became feral.[34]

Feral pigs

Pigs have escaped from farms and gone feral in many parts of the world. Feral pigs in the southeastern United States have migrated north to the Midwest, where many state agencies have programs to remove them.[35][36][37] Feral pigs in New Zealand and northern Queensland have caused substantial environmental damage.[38][39] Feral hybrids of the European wild boar with the domestic pig are disruptive to both environment and agriculture, as they destroy crops, spread animal diseases including Foot-and-mouth disease, and consume wildlife such as juvenile seabirds and young tortoises.[40] Feral pig damage is especially an issue in southeastern South America.[41][42]

Reproduction

Physiology

Female pigs reach sexual maturity at 3–12 months of age and come into estrus every 18–24 days if they are not successfully bred. The variation in ovulation rate can be attributed to intrinsic factors such as age and genotype, as well as extrinsic factors like nutrition, environment, and the supplementation of exogenous hormones. The gestation period averages 112–120 days.[43]

Estrus lasts two to three days, and the female's displayed receptiveness to mate is known as standing heat. Standing heat is a reflexive response that is stimulated when the female is in contact with the saliva of a sexually mature boar. Androstenol is one of the pheromones produced in the submaxillary salivary glands of boars that trigger the female's response.[44] The female cervix contains a series of five interdigitating pads, or folds, that hold the boar's corkscrew-shaped penis during copulation.[45] Females have bicornuate uteruses and two conceptuses must be present in both uterine horns to enable pregnancy to proceed.[46] The mother's body recognises that it is pregnant on days 11 to 12 of pregnancy, and is marked by the corpus luteum's producing the sex hormone progesterone.[47] To sustain the pregnancy, the embryo signals to the corpus luteum with the hormones estradiol and prostaglandin E2.[48] This signaling acts on both the endometrium and luteal tissue to prevent the regression of the corpus luteum by activation of genes that are responsible for corpus luteum maintenance.[49] During mid to late pregnancy, the corpus luteum relies primarily on luteinizing hormone for maintenance until birth.[48]

Archeological evidence indicates that medieval European pigs farrowed, or bore a litter of piglets, once per year.[50] By the nineteenth century, European piglets routinely double-farrowed, or bore two litters of piglets per year. It is unclear when this shift occurred.[51] Pigs have a maximum life span of about 27 years.[52]

Nest-building

A characteristic of pigs which they share with carnivores is nest-building. Sows root in the ground to create depressions the size of their body, and then build nest mounds, using twigs and leaves, softer in the middle, in which to give birth. When the mound reaches the desired height, she places large branches, up to 2 metres in length, on the surface. She enters the mound and roots around to create a depression within the gathered material. She then gives birth in a lying position, unlike other artiodactyls which usually stand while birthing.[53]

Nest-building occurs during the last 24 hours before the onset of farrowing, and becomes most intense 12 to 6 hours before farrowing.[54] The sow separates from the group and seeks a suitable nest site with well-drained soil and shelter from rain and wind. This provides the offspring with shelter, comfort, and thermoregulation. The nest provides protection against weather and predators, while keeping the piglets close to the sow and away from the rest of the herd. This ensures they do not get trampled on, and prevents other piglets from stealing milk from the sow.[55] The onset of nest-building is triggered by a rise in prolactin level, caused by a decrease in progesterone and an increase in prostaglandin; the gathering of nest material seems to be regulated more by external stimuli such as temperature.[54]

Nursing and suckling

Pigs have complex nursing and suckling behaviour.[56] Nursing occurs every 50–60 minutes, and the sow requires stimulation from piglets before milk let-down. Sensory inputs (vocalisation, odours from mammary and birth fluids, and hair patterns of the sow) are particularly important immediately post-birth to facilitate teat location by the piglets.[57] Initially, the piglets compete for position at the udder; then the piglets massage around their respective teats with their snouts, during which time the sow grunts at slow, regular intervals. Each series of grunts varies in frequency, tone and magnitude, indicating the stages of nursing to the piglets.[58]

The phase of competition for teats and of nosing the udder lasts for about a minute, ending when milk begins to flow. The piglets then hold the teats in their mouths and suck with slow mouth movements (one per second), and the rate of the sow's grunting increases for approximately 20 seconds. The grunt peak in the third phase of suckling does not coincide with milk ejection, but rather the release of oxytocin from the pituitary into the bloodstream.[59] Phase four coincides with the period of main milk flow (10–20 seconds) when the piglets suddenly withdraw slightly from the udder and start sucking with rapid mouth movements of about three per second. The sow grunts rapidly, lower in tone and often in quick runs of three or four, during this phase. Finally, the flow stops and so does the grunting of the sow. The piglets may dart from teat to teat and recommence suckling with slow movements, or nosing the udder. Piglets massage and suckle the sow's teats after milk flow ceases as a way of letting the sow know their nutritional status. This helps her to regulate the amount of milk released from that teat in future sucklings. The more intense the post-feed massaging of a teat, the more milk that teat later releases.[60]

-

Sows typically have 12–14 nipples.

-

A sow with suckling piglets

Teat order

In pigs, dominance hierarchies are formed at an early age. Piglets are precocious, and attempt to suckle soon after being born. The piglets are born with sharp teeth and fight for the anterior teats, as these produce more milk. Once established, this teat order remains stable; each piglet tends to feed on a particular teat or group of teats.[53] Stimulation of the anterior teats appears to be important in causing milk letdown,[61] so it might be advantageous to the entire litter to have these teats occupied by healthy piglets. Piglets locate teats by sight and then by olfaction.[62]

Behaviour

Social

Pig behaviour is intermediate between that of other artiodactyls and of carnivores.[53] Pigs seek out the company of other pigs and often huddle to maintain physical contact, but they do not naturally form large herds. They live in groups of about 8–10 adult sows, some young individuals, and some single males.[54] Pigs confined in a simplified, crowded, or uncomfortable environment may resort to tail-biting; farmers sometimes dock the tails of pigs to prevent the problem, or may enrich the environment with toys or other objects to reduce the risk.[63][64]

Temperature control

Because of their relative lack of sweat glands, pigs often control their body temperature using behavioural thermoregulation. Wallowing, coating the body with mud, is a common behaviour.[9] They do not submerge completely under the mud, but vary the depth and duration of wallowing depending on environmental conditions.[9] Adult pigs start wallowing once the ambient temperature is around 17–21 °C (63–70 °F). They cover themselves in mud from head to tail.[9] They may use mud as a sunscreen, or to keep parasites away.[9] Most bristled pigs "blow their coat", meaning that they shed most of the longer, coarser stiff hair once a year, usually in spring or early summer, to prepare for the warmer months ahead.[65]

Eating, feeding, sleeping

Where pigs are allowed to roam freely, they walk roughly 4 km daily, scavenging within a home range of around a hectare. Farmers in Africa often choose such a low-input, free-range production system.[66]

If conditions permit, pigs feed continuously for many hours and then sleep for many hours, in contrast to ruminants, which tend to feed for a short time and then sleep for a short time. Pigs are omnivorous and versatile in their feeding behaviour. They primarily eat leaves, stems, roots, fruits, and flowers.[67]

Rooting is an instinctual comforting behaviour in pigs characterized by nudging the snout into something. It first happens when piglets are born to obtain their mother's milk, and can become a habitual, obsessive behaviour, most prominent in animals weaned too early. Pigs root and dig into the ground to forage for food. Rooting is also a means of communication.[68]

Intelligence

Pigs are relatively intelligent animals, roughly on par with dogs. They distinguish each other as individuals, spend time in play, and form structured communities. They have good long-term memory and they experience emotions, changing their behaviour in response to the emotional states of other pigs. In terms of experimental tasks, pigs can perform tasks that require them to identify the locations of objects; they can solve mazes; and they can work with a simple language of symbols. They display self-recognition in a mirror. Pigs have been trained to associate different sorts of music (Bach and a military march) with food and social isolation respectively, and could communicate the resulting positive or negative emotion to untrained pigs.[70][71] Pigs can be trained to use a joystick with their snout to select a target on screen.[69]

Senses

Pigs have panoramic vision of approximately 310° and binocular vision of 35° to 50°. It is thought they have no eye accommodation.[72] Other animals that have no accommodation, e.g. sheep, lift their heads to see distant objects.[73] The extent to which pigs have colour vision is still a source of some debate; however, the presence of cone cells in the retina with two distinct wavelength sensitivities (blue and green) suggests that at least some colour vision is present.[74]

Pigs have a well-developed sense of smell; this is exploited in Europe where trained pigs find underground truffles.[75] Pigs have 1,113 genes for smell receptors, compared to 1,094 in dogs; this may indicate an acute sense of smell, but against this, insects have only around 50 to 100 such genes but make extensive use of olfaction.[76] Olfactory rather than visual stimuli are used in the identification of other pigs.[77] Hearing is well developed; sounds are localised by moving the head. Pigs use auditory stimuli extensively for communication in all social activities.[78] Alarm or aversive stimuli are transmitted to other pigs not only by auditory cues but also by pheromones.[79] Similarly, recognition between the sow and her piglets is by olfactory and vocal cues.[80]

Pests and diseases

Pigs are subject to many pests and diseases which can seriously affect productivity and cause death. These include parasites such as Ascaris roundworms, virus diseases such as the tick-borne African Swine Fever, bacterial infections such as Clostridium, arthritis caused by Mycoplasma, and stillbirths caused by Parvovirus.[81]

Some parasites of pigs are a public health risk as they can be transmitted to humans in undercooked pork. These are the pork tapeworm Taenia solium; a protozoan, Toxoplasma gondii; and a nematode, Trichinella spiralis. Transmission can be prevented by thorough sanitation on the farm; by meat inspection and careful commercial processing; and by thorough cooking, or alternatively by sufficient freezing and curing.[82]

In agriculture

Production

Pigs have been raised outdoors, and sometimes allowed to forage in woods or pastures. In industrialized nations, pig production has largely switched to large-scale intensive pig farming. This has lowered production costs but has caused concern about possible cruelty. As consumers have become concerned with the humane treatment of livestock, demand for pasture-raised pork in these nations has increased.[83] Most pigs in the US receive ractopamine, a beta-agonist drug, which promotes muscle instead of fat and quicker weight gain, requiring less feed to reach finishing weight, and producing less manure. China has requested that pork exports be ractopamine-free.[84] With a population of around 1 billion individuals, the domesticated pig is one of the most numerous large mammals on the planet.[85][86]

Like all animals, pigs are susceptible to adverse impacts from climate change, such as heat stress from increased annual temperatures and more intense heatwaves. Heat stress has increased rapidly between 1981 and 2017 on pig farms in Europe. Installing a ground-coupled heat exchanger is an effective intervention.[87]

-

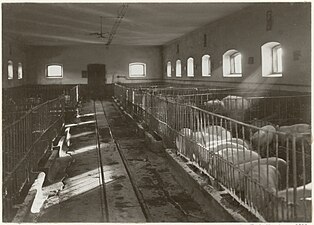

Indoor pig farm, Sweden, 1911

-

Sow in stall with separate piglet balcony to prevent crushing, Germany, 1959

-

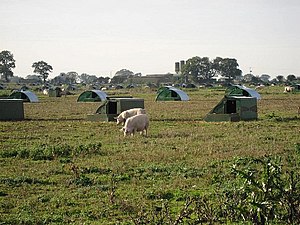

Free range pigs with field shelters, England, 2006

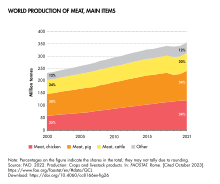

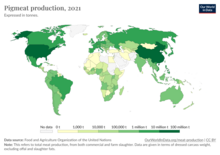

- FAO data for 2021

-

Pork is tied with chicken as the most commonly consumed meat worldwide.

-

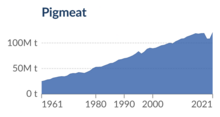

Pork production has grown substantially over the recent 60 years.

-

Production of pork worldwide, by country in 2021.

Breeds

Around 600 breeds of pig have been created by farmers around the world, mainly in Europe and Asia, differing in coloration, shape, and size.[88] According to The Livestock Conservancy, as of 2016, three breeds of pig are critically rare (having a global population of fewer than 2000). They are the Choctaw hog, the Mulefoot, and the Ossabaw Island hog.[89] The smallest known pig breed in the world is the Göttingen minipig, typically weighing about 26 kilograms (57 lb) as a healthy, full-grown adult.[90]

As pets

Vietnamese Pot-bellied pigs, a miniature breed of pig, have been kept as pets in the United States, beginning in the latter half of the 20th century.

Pigs are intelligent, social creatures. They are considered hypoallergenic and are known to do quite well with people who have the usual animal allergies. Since these animals are known to have a life expectancy of 15 to 20 years, they require a long-term commitment.

Given pigs are bred primarily as livestock and have not been bred as companion animals for very long, selective breeding for a placid or biddable temperament is not well established. Pigs have radically different psychology and behaviours compared to dogs, and exhibit fight-or-flight instincts, an independent nature, and natural assertiveness.[91] Male and female swine that have not been de-sexed may express unwanted aggressive behavior, and are prone to developing serious health issues.[92] As rooting is found to be comforting, pigs kept in the house may root household objects, furniture or surfaces. Pet pigs should be let outside to allow them to fulfill their natural desire of rooting around.

Economy

| Global pig stock | |

|---|---|

| in 2019 | |

| Number in millions | |

| 1. China (Mainland) | 310.4 (36.5%) |

| 2. European Union | 143.1 (16.83%) |

| 3. United States | 78.7 (9.26%) |

| 4. Brazil | 40.6 (4.77%) |

| 5. Russia | 23.7 (2.79%) |

| 6. Myanmar | 21.6 (2.54%) |

| 7. Vietnam | 19.6 (2.31%) |

| 8. Mexico | 18.4 (2.16%) |

| 9. Canada | 14.1 (1.66%) |

| 10. Philippines | 12.7 (1.49%) |

| World total | 850.3 |

| Source: UN Food and Agriculture Organization | |

Approximately 1.5 billion pigs are slaughtered each year for meat.[93]

The pork belly futures contract became an icon of commodities trading. It appears in depictions of the arena in popular entertainment, such as the 1983 film Trading Places.[94] Trade in pork bellies declined, and they were delisted from the Chicago Mercantile Exchange in 2011.[94][95]

In 2023, China produced more pork than any other country, 55 million tonnes, followed by the European Union with 22.8 million tonnes and the United States with 12.5 million tonnes. Global production in 2023 was 120 million tonnes.[96] India, despite its large population, consumed under 0.3 million tonnes of pork in 2023.[97] International trade in pork (meat not consumed in the producing country) reached 13 million tonnes in 2020.[98]

Uses

Products

Pigs are farmed primarily for meat, called pork. Pork is eaten in the form of pork chops, loin or rib roasts, shoulder joints, steaks, and loin (also called fillet). The many meat products made from pork include ham, bacon (mainly from the back and belly), and sausages.[99] Pork is further made into charcuterie products such as terrines, galantines, pâtés and confits.[100] Some sausages such as salami are fermented and air-dried, to be eaten raw. There are many types, the original Italian varieties including Genovese, Milanese, and Cacciatorino, with spicier kinds from the South of Italy including Calabrese, Napoletano, and Peperone.[101]

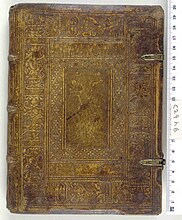

The hide is made into pigskin leather, which is soft and durable; it can be brushed to form suede leather. These are used for products such as gloves, wallets, suede shoes, and leather jackets.[102] In the 16th century, pig skin was the most popular book-binding material in Germany, though calf skin was more common elsewhere.[103]

-

Pork chops

-

Streaky or side bacon

-

Salami, a fermented and air-dried sausage, originally made in Italy

-

A 16th century book bound in pig skin

-

A woman's suede gloves, England, c. 1820

In medicine

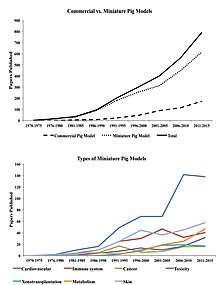

Pigs, both as live animals and as a source of post-mortem tissues, are valuable animal models because of their biological, physiological, and anatomical similarities to human beings. For instance, human skin is very similar to the pigskin, therefore pigskin has been used in many preclinical studies.[105][106]

Pigs are good non-human candidates for organ donation to humans, and in 2021 became the first animal to successfully donate an organ to a human body.[107][108] The procedure used a donor pig genetically engineered not to have a specific carbohydrate that the human body considers a threat–Galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose.[109] Pigs are good for human donation as the risk of cross-species disease transmission is reduced by the considerable phylogenetic distance from humans.[110] They are readily available, and the danger of creating new human diseases is low as domesticated pigs have been in close contact with humans for thousands of years.[111]

Impact of pig husbandry

On public health

Pig farms can serve as reservoirs of viral diseases that are dangerous to humans and so contribute to their outbreaks in human populations.[112] The 2009 swine flu pandemic was caused by an influenza A variant which had first emerged in pigs.[113] Pigs were also essential to the first outbreak of the Nipah virus in 1999, with 93% of the infected humans having had contact with pigs.[112] While Japanese encephalitis is primarily spread by mosquitoes, pigs are a known intermediary host.[114] There is also a potential for porcine coronaviruses such as porcine epidemic diarrhea virus or swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus to spill over into human populations.[112]

On the environment

As with the other forms of meat, producing pork is more energy-intensive than plant-based foods, and it is associated with more greenhouse gas emissions per calorie. However, emissions from pork are many times smaller than those of beef, veal and mutton, though larger than of chicken meat.[115]

Intensive pig production is also associated with water pollution concerns, as the swine waste is often stored above ground in so-called lagoons. These lagoons typically have high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus, and can contain toxic heavy metals like zinc and copper, microbial pathogens, or hold elevated concentrations of pharmaceuticals from subtherapeutic antibiotic use in swine.[116] This wastewater from lagoons is liable to reach groundwater on farms, though there is little evidence for it reaching deeper into local drinking water supplies.[117] However, lagoon spills, such as from heavy rains in the wake of a hurricane, can lead to fish kills and algal blooms in local rivers.[116] In the United States, 35,000 mi (56,000 km) of river across over 20 states were estimated to have been contaminated by manure leakage as of 2015.[118] There is also evidence that evaporation from lagoons can cause nitrogen and phosphorus to spread through the air as dry particles then reach other water basins when they fall out through dry deposition. This process then also contributes to water eutrophication.[116]

On animal welfare

Intensive pig production involves practices such as castration, earmarking, tattooing for litter identification, tail docking, which are often done without the use of anesthetic.[119] [120] Painful teeth clipping of piglets is also done to curtail cannibalism, behavioural instability and aggression, and tail biting, which are induced by the cramped environment.[121][122] In English indoor farming, young pigs (less than 110kg in weight) are allowed to be kept with less than one square meter of space per pig.[123]

Pigs often begin life in a farrowing or gestation crate, which is a small pen with a central cage, designed to allow the piglets to feed from their mother while preventing her from attacking or crushing them.[124] The crates are so small that the mother sows cannot turn around.[125][126] While wild piglets remain with their mothers for around 12 to 14 weeks, farmed piglets are weaned and removed from their mothers at between two and five weeks old.[127][128] Of the piglets born alive, 10% to 18% will not reach weaning age, instead succumbing to disease, starvation, dehydration, or accidental crushing by their mothers.[121][129] Unusually small runt piglets are typically killed immediately by staff through blunt trauma to the head.[130][131] Further, intensive farming involves sows giving birth to large litter sizes at an unnatural frequency, which increases the rate of stillborn piglets, and causes as many as 25%-50% of sows to die of prolapse.[132][133]

In culture

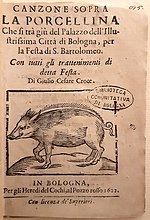

Pigs, widespread in societies around the world since Neolithic times, have been used for many purposes in art, literature, and other expressions of human culture. In classical times, the Romans considered pork the finest of meats, enjoying sausages, and depicting them in their art.[134] Across Europe, pigs have been celebrated in carnivals since the Middle Ages,[135] becoming specially important in Medieval Germany in cities such as Nuremberg,[136] and in Early Modern Italy in cities such as Bologna.[137][138] Pigs, especially miniature breeds, are occasionally kept as pets.[139][140]

In literature, both for children[141] and adults, pig characters appear in allegories, comic stories, and serious novels.[135][142][143] In art, pigs have been represented in a wide range of media and styles from the earliest times in many cultures.[144] Pig names are used in idioms and animal epithets, often derogatory, since pigs have long been linked with dirtiness and greed,[145][146] while places such as Swindon are named for their association with swine.[147] The eating of pork is forbidden in Islam and Judaism,[148] but pigs are sacred in some other religions.[149][150]

-

Bronze pig sculpture, Zhou dynasty

-

Painting of Saint Anthony with a pig in background by Piero di Cosimo c. 1480

-

Canzone Sopra La Porcellina ("Song Upon the Piglet") by Giulio Cesare Croce, Bologna, 1622

-

Pigling Bland setting out on his adventures

References

- ^ Groves, Colin P. (1995). "On the nomenclature of domestic animals". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 52 (2): 137–141. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.6749. Biodiversity Heritage Library

- ^ a b "Sus scrofa (wild boar)". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ Lockhart, Kim. "American Wild Game / Feral Pigs / Hogs / Pigs / Wild Boar". gunnersden.com. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ "Royal visit delights at the Three Counties Show". Malvern Gazette. 15 June 2007.

- ^ Bradford, Alina; Dutfield, Scott (5 October 2018). "Pigs, Hogs & Boars: Facts About Swine". LiveScience. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ Sumena, K. B.; Lucy, K. M.; Chungath, J.J.; Ashok, N.; Harshan, K. R. (2010). "Regional histology of the subcutaneous tissue and the sweat glands of large white Yorkshire pigs". Tamil Nadu Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences. 6 (3): 128–135.

- ^ Folk, G.E.; Semken, H.A. (1991). "The evolution of sweat glands". International Journal of Biometeorology. 35 (3): 180–186. Bibcode:1991IJBm...35..180F. doi:10.1007/bf01049065. PMID 1778649. S2CID 28234765.

- ^ "Sweat like a pig?". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 22 April 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Bracke, M. B. M. (2011). "Review of wallowing in pigs: Description of the behaviour and its motivational basis". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 132 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2011.01.002.

- ^ Drabeck, D. H.; Dean, A. M.; Jansa, S.A. (1 June 2015). "Why the honey badger don't care: Convergent evolution of venom-targeted nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mammals that survive venomous snake bites". Toxicon. 99: 68–72. Bibcode:2015Txcn...99...68D. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.03.007. PMID 25796346.

- ^ "Pros and Cons of Potbellied Pigs". Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ Li, Mingzhou; Chen, Lei; Tian, Shilin; Lin, Yu; Tang, Qianzi; Zhou, Xuming; Li, Diyan; Yeung, Carol K. L.; Che, Tiandong; Jin, Long; Fu, Yuhua (1 May 2017). "Comprehensive variation discovery and recovery of missing sequence in the pig genome using multiple de novo assemblies". Genome Research. 27 (5): 865–874. doi:10.1101/gr.207456.116. PMC 5411780. PMID 27646534.

- ^ Warr, A.; Affara, N.; Aken, B.; Beiki, H.; Bickhart, D. M.; Billis, K.; et al. (2020). "An improved pig reference genome sequence to enable pig genetics and genomics research". GigaScience. 9 (6): giaa051. doi:10.1093/gigascience/giaa051. PMC 7448572. PMID 32543654.

- ^ Karlsson, Max; Sjöstedt, Evelina; Oksvold, Per; Sivertsson, Åsa; Huang, Jinrong; Álvez, María Bueno; et al. (25 January 2022). "Genome-wide annotation of protein-coding genes in pig". BMC Biology. 20 (1): 25. doi:10.1186/s12915-022-01229-y. PMC 8788080. PMID 35073880.

- ^ Wu, Gui-Sheng; Pang, Jun-feng; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2006). "Molecular phylogeny and phylogeography of Suidae". Zoological Research. 27 (2): 197–201.

- ^ "Taxonomy Browser". ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ Gentry, Anthea; Clutton-Brock, Juliet; Colin P. Groves (2004). "The naming of wild animal species and their domestic derivatives" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 31 (5): 645–651. Bibcode:2004JArSc..31..645G. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2003.10.006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2011.

- ^ Gentry, Anthea; Clutton-Brock, Juliet; Groves, Colin P. (1996). "Proposed conservation of usage of 15 mammal specific names based on wild species which are antedated by or contemporary with those based on domestic animals". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 53: 28–37. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.14102.

- ^ "Explore the Database". www.mammaldiversity.org. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ Bosse, Mirte (26 December 2018). "A Genomics Perspective on Pig Domestication". Animal Domestication. IntechOpen. doi:10.5772/intechopen.82646. ISBN 978-1-83880-174-8.

- ^ Ottoni, C; Flink, LG.; Evin, A.; Geörg, C.; De Cupere, B.; Van Neer, W.; et al. (2013). "Pig Domestication and Human-Mediated Dispersal in Western Eurasia Revealed through Ancient DNA and Geometric Morphometrics". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 30 (4): 824–32. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss261. PMC 3603306. PMID 23180578.

our data suggest a narrative that begins with the domestication of pigs in Southwest Asia, at Upper Tigris sites including Çayönü Tepesi (Ervynck et al. 2001) and possibly Upper Euphrates sites including Cafer Höyük (Helmer 2008) and Nevalı Çori (Peters et al. 2005)

- ^ Rosenberg, M.; Nesbitt, R.; Redding, R. W.; Peasnall, BL (1998). "Hallan Çemi, pig husbandry, and post-Pleistocene adaptations along the Taurus-Zagros Arc (Turkey)". Paléorient. 24 (1): 25–41. doi:10.3406/paleo.1998.4667. S2CID 85302206.

- ^ Vigne, J. D.; Zazzo, A.; Saliège, J.F.; Poplin, F.; Guilaine, J.; Simmons, A. (2009). "Pre-Neolithic wild boar management and introduction to Cyprus more than 11,400 years ago". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (38): 16135–16138. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10616135V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0905015106. PMC 2752532. PMID 19706455.

- ^ Lander, Brian; Schneider, Mindi; Brunson, Katherine (2019). "A History of Pigs in China: From Curious Omnivores to Industrial Pork". Journal of Asian Studies. 79 (4): 865–889. doi:10.1017/S0021911820000054. S2CID 225700922.

- ^ a b Giuffra, E.; Kijas, J. M.; Amarger, V.; Carlborg, O.; Jeon, J. T.; Andersson, L. (2000). "The origin of the domestic pig: independent domestication and subsequent introgression". Genetics. 154 (4): 1785–1791. doi:10.1093/genetics/154.4.1785. PMC 1461048. PMID 10747069.

- ^ Jean-Denis Vigne; Anne Tresset; Jean-Pierre Digard (3 July 2012). History of domestication (PDF) (Speech).

- ^ Price, Max (March 2020). "The Genesis of the Near Eastern Pig". American Society of Overseas Research. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ Frantz, L (2015). "Evidence of long-term gene flow and selection during domestication from analyses of Eurasian wild and domestic pig genomes". Nature Genetics. 47 (10): 1141–1148. doi:10.1038/ng.3394. PMID 26323058. S2CID 205350534.

- ^ Pennisi, E. (2015). "The taming of the pig took some wild turns". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aad1692.

- ^ Frantz, Laurent A. F.; Haile, James; Lin, Audrey T.; Scheu, Amelie; Geörg, Christina; Benecke, Norbert; et al. (2019). "Ancient pigs reveal a near-complete genomic turnover following their introduction to Europe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (35): 17231–17238. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11617231F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1901169116. PMC 6717267. PMID 31405970.

- ^ BBC News, "Pig DNA reveals farming history" 4 September 2007. The report concerns an article in the journal PNAS

- ^ Larson, G.; Albarella, U.; Dobney, K.; Rowley-Conwy, P.; Schibler, J.; Tresset, A.; et al. (2007). "Ancient DNA, pig domestication, and the spread of the Neolithic into Europe" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (39): 15276–15281. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10415276L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703411104. PMC 1976408. PMID 17855556.

- ^ Torrejón, Fernando; Cisternas, Marco; Araneda, Alberto (2004). "Efectos ambientales de la colonización española desde el río Maullín al archipiélago de Chiloé, sur de Chile" [Environmental effects of the spanish colonization from de Maullín river to the Chiloé archipelago, southern Chile]. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural (in Spanish). 77 (4): 661–677. doi:10.4067/s0716-078x2004000400009.

- ^ II.G.13. – Hogs. Archived 20 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Feral Hogs in Missouri". Missouri Department of Conservation. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Feral Hog Hunting Regulations". agfc.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Feral Hog Management". Georgia DNR – Wildlife Resources Division. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Yoon, Carol Kaesuk (2 December 1992). "Alien Species Threaten Hawaii's Environment". The New York Times.

- ^ "Introduced Birds and Mammals in New Zealand and Their Effect on the Environment – NZETC". nzetc.org.

- ^ "World's 100 most destructive species named". The Independent. 21 November 2004. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ Bauru; Marília (12 April 2013). "Autorização para abate do javaporco tranquiliza produtores em Assis, SP". Bauru e Marília.

- ^ "IBAMA authorizes capture and slaughter of 'javaporcos' – Folha do Sul Gaúcho". Archived from the original on 3 July 2017.

- ^ "Feral Hog Reproductive Biology". 16 May 2012. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015.

- ^ "G2312 Artificial Insemination in Swine: Breeding the Female". University of Missouri Extension. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "The Female – Swine Reproduction". livestocktrail.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ Bazer, F. W.; Vallet, J. L.; Roberts, R. M.; Sharp, D. D.; Thatcher, W. W. (1986). "Role of conceptus secretory products in establishment of pregnancy". J. Reprod. Fertil. 76 (2): 841–850. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0760841. PMID 3517318.

- ^ Bazer, Fuller W.; Song, Gwonhwa; Kim, Jinyoung; Dunlap, Kathrin A.; Satterfield, Michael Carey; Johnson, Gregory A.; Burghardt, Robert C.; Wu, Guoyao (1 January 2012). "Uterine biology in pigs and sheep". Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology. 3 (1): 23. doi:10.1186/2049-1891-3-23. PMC 3436697. PMID 22958877.

- ^ a b Ziecik, A. J.; et al. (2018). "Regulation of the porcine corpus luteum during pregnancy". Reproduction. 156 (3): R57 – R67. doi:10.1530/rep-17-0662. PMID 29794023.

- ^ Waclawik, A.; et al. (2017). "Embryo-maternal dialogue during pregnancy establishment and implantation in the pig". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 84 (9): 842–855. doi:10.1002/mrd.22835. PMID 28628266.

- ^ Ervynck, Anton; Dobney, Keith (2002). "A Pig for all Seasons? Approaches to the Assessment of Second Farrowing in Archaeological Pig Populations". Archaeofauna (11): 7–22. doi:10.15366/archaeofauna2002.11.001.

- ^ Bintliff, J.; Earle, T.; Peebles, C. (2008). A Companion to Archaeology. Wiley. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-470-99860-1.

- ^ Hoffman, J.; Valencak, T. G. (2020). "A short life on the farm: aging and longevity in agricultural, large-bodied mammals". GeroScience. 42 (3): 909–922. doi:10.1007/s11357-020-00190-4. PMC 7286991. PMID 32361879.

- ^ a b c Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1987). A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b c Algers, Bo; Uvnäs-Moberg, Kerstin (1 June 2007). "Maternal behavior in pigs". Hormones and Behavior. Reproductive Behavior in Farm and Laboratory Animals: 11th Annual Meeting of the Society for Behavioral Neuroendocrinology. 52 (1): 78–85. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.03.022. PMID 17482189. S2CID 9742677.

- ^ Wischner, D.; Kemper, N.; Krieter, J. (2009). "Nest-building behaviour in sows and consequences for pig husbandry". Livestock Science. 124 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2009.01.015.

- ^ Fraser, D. (1980). "A review of the behavioural mechanisms of milk ejection of the domestic pig". Applied Animal Ethology. 6 (3): 247–256. doi:10.1016/0304-3762(80)90026-7.

- ^ Rohde Parfet, K.A.; Gonyou, H.W. (1991). "Attraction of newborn piglets to auditory, visual, olfactory and tactile stimuli". Journal of Animal Science. 69 (1): 125–133. doi:10.2527/1991.691125x. PMID 2005005. S2CID 31788525.

- ^ Algers, B (1993). "Nursing in pigs: communicating needs and distributing resources". Journal of Animal Science. 71 (10): 2826–2831. doi:10.2527/1993.71102826x. PMID 8226386.

- ^ Castren, H.; Algers, B.; Jensen, P.; Saloniemi, H. (1989). "Suckling behaviour and milk consumption in newborn piglets as a response to sow grunting". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 24 (3): 227–238. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(89)90069-5.

- ^ Jensen, P.; Gustafsson, G.; Augustsson, H. (1998). "Massaging after milk ejection in domestic pigs – an example of honest begging?". Animal Behaviour. 55 (4): 779–786. doi:10.1006/anbe.1997.0651. PMID 9632466. S2CID 12493158.

- ^ Fraser, D. (1973). "The nursing and suckling behaviour in pigs. I. The importance of stimulation of the anterior teats". British Veterinary Journal. 129 (4): 324–336. doi:10.1016/s0007-1935(17)36434-5. PMID 4733757.

- ^ Jeppesen, L.E. (1982). "Teat-order in groups of piglets reared on an artificial sow. II. Maintenance of teat order with some evidence for the use of odour cues". Applied Animal Ethology. 8 (4): 347–355. doi:10.1016/0304-3762(82)90067-0.

- ^ "Tail docking and tail biting in pigs". Animal Husbandry Development Board. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Pig Health- Tail Biting". National Animal Disease Information Service. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "Blowing Coat – Mini Pig Shedding FAQ". americanminipigassociation.com. 2 April 2016.

- ^ Thomas, Lian F; de Glanville, William A; Cook, Elizabeth A; Fèvre, Eric M (2013). "The spatial ecology of free-ranging domestic pigs (Sus scrofa) in western Kenya". BMC Veterinary Research. 9 (1): 46. doi:10.1186/1746-6148-9-46. ISSN 1746-6148. PMC 3637381. PMID 23497587.

- ^ Kongsted, A. G.; Horsted, K.; Hermansen, J. E. (2013). "Free-range pigs foraging on Jerusalem artichokes (Helianthus tuberosus L.) – Effect of feeding strategy on growth, feed conversion and animal behaviour". Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section A. 63 (2): 76–83. doi:10.1080/09064702.2013.787116. S2CID 84886946.

- ^ "Rooting & Nudging Behaviors in Mini Pigs". americanminipigassociation.com. 8 June 2016.

- ^ a b Croney, Candace C.; Boysen, Sarah T. (11 February 2021). "Acquisition of a Joystick-Operated Video Task by Pigs (Sus scrofa)". Frontiers in Psychology. 12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631755. PMC 7928376. PMID 33679560.

- ^ Colvin, Christina M.; Marino, Lori. "Signs of Intelligent Life". Natural History Magazine. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ Angier, Natalie (9 November 2009). "Pigs Prove to Be Smart, if Not Vain". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ "Animalbehaviour.net (Pigs)". Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ "Animalbehaviour.net (Sheep)". Archived from the original on 26 December 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ Lomas, C.A.; Piggins, D.; Phillips, C.J.C. (1998). "Visual awareness". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 57 (3–4): 247–257. doi:10.1016/s0168-1591(98)00100-2.

- ^ Sullivan, Walter (24 March 1982). "Truffles: Why Pigs Can Sniff Them Out". The New York Times.

- ^ McGlone, John J.; Archer, Courtney; Henderson, Madelyn (25 October 2022). "Interpretive review: Semiochemicals in domestic pigs and dogs". Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 9. doi:10.3389/fvets.2022.967980. ISSN 2297-1769. PMC 9640746. PMID 36387395.

- ^ Houpt, Katherine A. (27 March 2018). "2. Aggression and Social Structure". Domestic Animal Behavior for Veterinarians and Animal Scientists. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-23276-6.

- ^ Gonyou, H. W. (2001). "The Social Behaviour of Pigs". In Keeling, L. J.; Gonyou, H. W. (eds.). Social behaviour in farm animals. CABI Publishing. pp. 147–176. doi:10.1079/9780851993973.0000. ISBN 978-0-85199-397-3.

- ^ Vieuille-Thomas, C.; Signoret, J. P. (1992). "Pheromonal transmission of an aversive experience in domestic pigs". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 18 (9): 1551–1557. Bibcode:1992JCEco..18.1551V. doi:10.1007/bf00993228. PMID 24254286. S2CID 4386919.

- ^ Jensen, P.; Redbo, I. (1987). "Behaviour during nest leaving in free-ranging domestic pigs". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 18 (3–4): 355–362. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(87)90229-2.

- ^ "Disease A-Z for Pigs". NADIS Animal Health Skills. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ Gamble, H. R. (1 August 1997). "Parasites associated with pork and pork products". Revue Scientifique et Technique de l'OIE. 16 (2): 496–506. doi:10.20506/rst.16.2.1032. PMID 9501363.

- ^ Strom, Stephanie (2 January 2014). "Demand Grows for Hogs That Are Raised Humanely Outdoors". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Charles, Dan (14 August 2015). "A Muscle Drug For Pigs Comes Out Of The Shadows". NPR.

- ^ "PSD Online". fas.usda.gov.

- ^ Swine Summary Selected Countries Archived 29 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service, (total number is Production (Pig Crop) plus Total Beginning Stocks

- ^ Mikovits, Christian; Zollitsch, Werner; Hörtenhuber, Stefan J.; Baumgartner, Johannes; Niebuhr, Knut; Piringer, Martin; et al. (22 January 2019). "Impacts of global warming on confined livestock systems for growing-fattening pigs: simulation of heat stress for 1981 to 2017 in Central Europe". International Journal of Biometeorology. 63 (2): 221–230. Bibcode:2019IJBm...63..221M. doi:10.1007/s00484-018-01655-0. PMID 30671619. S2CID 58951606.

- ^ Miao, Jian; Chen, Zitao; Zhang, Zhenyang; Wang, Zhen; Wang, Qishan; Zhang, Zhe; Pan, Yuchun (21 March 2023). "A web tool for the global identification of pig breeds". Genetics Selection Evolution. 55 (1): 18. doi:10.1186/s12711-023-00788-0. ISSN 1297-9686. PMC 10029154. PMID 36944938.

- ^ "The Livestock Conservancy". livestock Conservancy. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Taking good care of Ellegaard Göttingen Minipigs®" (PDF). Ellegaard Göttingen Minipigs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ "Info/Resource - Pigs 4 Ever - Gifts, supplies and resources for Pot-Bellied Pigs". pigs4ever.com. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Spay and Neuter – American Mini Pig Association". americanminipigassociation.com. 18 September 2014.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". fao.org. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ a b Davey, Monica (30 July 2011). "Trade in Pork Bellies Comes to an End, but the Lore Lives". The New York Times.

- ^ Garner, Carley (13 January 2010). "A Crash Course in Commodities". FT Press. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ "Global pork production in 2022 and 2023, by country". Statista. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ "Consumption volume of pork in India from 2013 to 2023". Statista. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ Ter Beek, Vincent (13 December 2023). "The remarkable dynamics of global pig meat trade". Pig Progress. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ "Pork Cuts". National Pork Board. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ Davidson, Alan (2014). "Charcuterie (with links to other chapters: Hams, Sausages, Terrines, Pâtés, Galantines, Crepinettes, Andouille and Andouillette, Blood Sausages, White Pudding, Tripe)". In Jaine, Tom (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Food (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-19-967733-7.

- ^ Davidson, Alan (2014). "Sausages of Italy". In Jaine, Tom (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Food (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 719. ISBN 978-0-19-967733-7.

- ^ "Pig leather". Leather Dictionary. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ "Cover to Cover: Exposing the Bookbinder's Ancient Craft". The University of Adelaide. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Gutierrez, Karina; Dicks, Naomi; Glanzner, Werner G.; Agellon, Luis B.; Bordignon, Vilceu (16 September 2015). "Efficacy of the porcine species in biomedical research". Frontiers in Genetics. 6: 293. doi:10.3389/fgene.2015.00293. PMC 4584988. PMID 26442109.

- ^ Herron, Alan J. (5 December 2009). "Pigs as Dermatologic Models of Human Skin Disease" (PDF). ivis.org. DVM Center for Comparative Medicine and Department of Pathology Baylor College of Medicine Houston, Texas. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Liu, J.; Kim, L.; Madsen, T.; Bouchard, G. F. "Comparison of Human, Porcine and Rodent Wound Healing With New Miniature Swine Study Data" (PDF). sinclairresearch.com. Sinclair Research Centre, Auxvasse, MO, USA; Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory, Columbia, Missouri. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ "Successful pig-to-human kidney transplant a "transformative moment"". www.yahoo.com. 20 October 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ Lapid, Nancy (20 October 2021). "U.S. surgeons successfully test pig kidney transplant in human patient". Reuters. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ "Progress in Xenotransplantation Opens Door to New Supply of Critically Needed Organs". NYU Langone News. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ Dooldeniya, M. D.; Warrens, A. N. (2003). "Xenotransplantation: Where are we today?". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 96 (3): 111–117. doi:10.1177/014107680309600303. PMC 539416. PMID 12612110.

- ^ Taylor, L. (2007) Xenotransplantation. Emedicine.com

- ^ a b c McLean, Rebecca; Graham, Simon P. (4 April 2022). "The pig as an amplifying host for new and emerging zoonotic viruses". One Health. 14. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2022.100384. PMC 8975596. PMID 35392655.

- ^ Mena, Ignacio; Nelson, Martha I.; Quezada-Monroy, Francisco; Dutta, Jayeeta; Cortes-Fernández, Refugio; Lara-Puente, J Horacio; et al. (28 June 2016). "Origins of the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic in swine in Mexico". eLife. 5. doi:10.7554/eLife.16777. ISSN 2050-084X. PMC 4957980. PMID 27350259.

- ^ "Japanese encephalitis". World Health Organization. December 2015. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2023 (Report). FAO. 2023. doi:10.4060/cc8166en. ISBN 978-92-5-138262-2.

- ^ a b c Burkholder, JoAnn; Libra, Bob; Weyer, Peter; Heathcote, Susan; Kolpin, Dana; Thorne, Peter S.; Wichman, Michael (14 November 2007). "Impacts of waste from concentrated animal feeding operations on water quality". Environmental Health Perspectives. 115 (2): 308–12. Bibcode:2007EnvHP.115..308B. doi:10.1289/ehp.8839. PMC 1817674. PMID 17384784.

- ^ Fridrich, Beata; Krčmar, Dejan; Dalmacija, Božo; Molnar, Jelena; Pešić, Vesna; Kragulj, Marijana; Varga, Nataša (19 January 2014). "Impact of wastewater from pig farm lagoons on the quality of local groundwater". Agricultural Water Management. 135: 40–53. Bibcode:2014AgWM..135...40F. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2013.12.014.

- ^ "Agriculture". www.epa.gov. 19 March 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ Cutler, R; Holyoake, P (2007). "The Structure and Dynamics of the Pig Meat Industry, prepared for Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry" (PDF). agriculture.gov.au.

- ^ "Video Gallery". aussiepigs.com. Archived from the original on 2 June 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Industry Focus". australianpork.com.au. Australian Pork Limited.

- ^ "The risks associated with tail biting in pigs and possible means to reduce the need for tail docking considering the different housing and husbandry systems - Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Animal Health and Welfare". EFSA Journal. 5 (12): 611. 2007. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2007.611.

- ^ "Key figures for pig accommodation in England – legislative requirements" (PDF). AHDB Pork. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2019.

- ^ Cutler, R; Holyoake, P. (2007). "The Structure and Dynamics of the Pig Meat Industry, prepared for Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry" (PDF).

- ^ "Opinion on Free Farrowing Systems" (PDF). Farm Animal Welfare Committee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2019.

- ^ "Farrowing Fact Sheet". Viva! - The Vegan Charity. 6 January 2016. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ "Pig welfare". Compassion in World Farming. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ "Revisiting Weaning Age Trends, Dynamics". Nationalhogfarmer.com. 15 October 2005. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ "Pre-weaning mortality". pigprogress.net. Pig Progress. 13 July 2010.

- ^ Model code of practice for the welfare of animals: Pigs, Primary Industries Report Series third edition. 2008.

- ^ "Best of British? The Pig Industry Exposed" (PDF). Animal Aid.

- ^ "Fact Sheet – 'Reproductive Health'" (PDF). australianpork.com.au. Australian Pork Limited. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Greenaway, Twilight (1 October 2018). "'We've bred them to their limit': death rates surge for female pigs in the US". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ MacKinnon, Michael (2001). "High on the Hog: Linking Zooarchaeological, Literary, and Artistic Data for Pig Breeds in Roman Italy". American Journal of Archaeology. 105 (4): 649–673. doi:10.2307/507411. JSTOR 507411. S2CID 193116973.

- ^ a b Komins, Benton Jay (2001). "Western Culture and the Ambiguous Legacies of the Pig". CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture. 3 (4). doi:10.7771/1481-4374.1137.

- ^ Newey, Adam (8 December 2014). "Nuremberg, Germany: celebrating the city's sausage". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "Eventi: Pane e salame" (in Italian). Istituzione Biblioteche Bologna. August 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Virbila, S. Irene (7 August 1988). "Fare of the Country; Mortadella: Bologna's Bologna". The New York Times.

- ^ Porter, Valerie; Alderson, Lawrence; Hall, Stephen J.G.; Sponenberg, D. Phillip (2016). "Pig". Mason's World Encyclopedia of Livestock Breeds and Breeding (6 ed.). CABI. p. 616. ISBN 978-1-7806-4794-4.

- ^ The Joy of Pigs/ Pigs as Pets. PBS Nature. Accessed June 2017.

- ^ Robinson, Robert D. (March 1968). "The Three Little Pigs: From Six Directions". Elementary English. 45 (3): 356–359. JSTOR 41386323.

- ^ Mullan, John (21 August 2010). "Ten of the best pigs in literature". The Guardian.

- ^ Bragg, Melvyn. "Topics - Pigs in literature". BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

Animal Farm ... Sir Gawain and the Green Knight ... The Mabinogion ... The Odyssey ... (In Our Time)

- ^ "Pig". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "Fine Swine". The Daily Telegraph. 2 February 2001.

- ^ Horwitz, Richard P. (2002). Hog Ties: Pigs, Manure, and Mortality in American Culture. University of Minnesota Press. p. 23. ISBN 0816641838.

- ^ Mills, A. D. (1993). A Dictionary of English Place-Names. Oxford University Press. pp. 150, 318. ISBN 0192831313.

- ^ Fran Markowitz; Nir Avieli, eds. (2023). Eating Religiously: Food and Faith in the 21st Century. Taylor & Francis. Interceding Kashrut. ISBN 9781000988154.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (2011). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. pp. 444–445. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ^ Bonwick, James (1894). "Sacred Pigs". Library Ireland.