Sharpening stone

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2009) |

Sharpening stones, or whetstones,[1] are used to sharpen the edges of steel tools such as knives through grinding and honing.

Such stones come in a wide range of shapes, sizes, and material compositions. They may be flat, for working flat edges, or shaped for more complex edges, such as those associated with some wood carving or woodturning tools. They may be composed of natural quarried material or from man-made material. They come in various grades, which refer to the grit size of the abrasive particles in the stone. (Grit size is given as a number, which indicates the spatial density of the particles; a higher number denotes a higher density and therefore smaller particles, which give a finer finish to the surface of the sharpened object.) Stones intended for use on a workbench are called bench stones, while small, portable ones, whose size makes it hard to draw large blades uniformly over them, especially "in the field", are called pocket stones.

Often whetstones are used with a cutting fluid to enhance sharpening and carry away swarf. Those used with water for this purpose are often called water stones or waterstones, those used with oil sometimes oil stones or oilstones.

Whetstones will wear away with use, typically in the middle. Tools sharpened in this groove will develop undesirable curves on the blade. In order to prevent this, a whetstone may be levelled out with sandpaper or a levelling or flattening stone.[2]

Terminology

[edit]The term is based on the word "whet", which means to sharpen a blade,[3][4] not on the word "wet". The verb nowadays to describe the process of using a sharpening stone for a knife is simply to sharpen, but the older term to whet is still sometimes used, though so rare in this sense that it is no longer mentioned in, for example, the Oxford Living Dictionaries.[5][6]

Natural stones

[edit]Natural whetstones are typically formed of quartz, such as novaculite. The Ouachita Mountains in Arkansas are noted as a source for these, giving them the name "Arkansas stones". Novaculite is very hard and has small crystals (3-5 microns), making it suitable for the later fine stages of knife sharpening. Novaculite and other stone formations are found around the world such as in Eastern Crete which produces a stone known as the Turkish Stone, mined in the Elounda mountain but sold all throughout the Levant (hence its name) since antiquity.[7]

Similar stones have been in use since antiquity. The Roman historian Pliny described use of several naturally occurring stones for sharpening in his Natural History. He describes the use of both oil and water stones and gives the locations of several ancient sources for these stones.[8]

One of the most well-regarded natural whetstones is the yellow-gray "Belgian Coticule", which has been legendary for the edge it can give to blades since Roman times, and has been quarried for centuries from the Ardennes. The slightly coarser and more plentiful "Belgian Blue" whetstone is found naturally with the yellow coticule in adjacent strata; hence two-sided whetstones are available, with a naturally occurring seam between the yellow and blue layers. These are highly prized for their natural elegance and beauty, and for providing both a fast-cutting surface for establishing a bevel and a finer surface for refining it. Different veins of this stone are suitable for knives, tools, and razors respectively. Certain versions (such as La Veinette) are very sought after for razor honing.[9]

The hard stone of Charnwood Forest in northwest Leicestershire, England, has been quarried for centuries,[10] and was a source of whetstones and quern-stones.

Natural stones are often prized for their natural beauty as stones and their rarity, adding value as collectors' items. Furthermore, each natural stone is different, and there are rare natural stones that contain abrasive particles with different properties than are currently available in artificial stones. [11] Two common stones in the UK are the Water of Ayr stone and the speckled Tam'o Shanter stone, both forms of slate used as razor oilstones.[7]

Artificial (synthetic) stones

[edit]Artificial stones usually come in the form of a bonded abrasive composed of a ceramic such as silicon carbide (carborundum); aluminium oxide (corundum, also known as water stone or India stone); and CBN (cubic boron nitride). They provide more aggressive cutting action than natural stones, and are used for the middle stages of knife sharpening, while natural stones are used for the later, finer stages.

They are commonly available as a double-sided block with a coarse grit on one side and a fine grit on the other enabling one stone to satisfy the basic requirements of sharpening. Some shapes are designed for specific purposes such as sharpening scythes, drills or serrations.[12]

Modern synthetic stones are generally of equal quality to natural stones, and are often considered superior in sharpening performance because of consistency of particle size and control over the properties of the stones. For example, the proportional content of abrasive particles as opposed to base or "binder" materials can be controlled to make the stone cut faster or more slowly, as desired.[13]

The use of natural stone for sharpening has diminished with the widespread availability of high-quality artificial stones with consistent particle size. As a result, the legendary Honyama mines in Kyoto, Japan, have been closed since 1967. Belgium currently has only a single mine that is still quarrying Coticules and their Belgian Blue Whetstone counterparts.[14]

Japanese natural and synthetic waterstones

[edit]

The Japanese traditionally use natural sharpening stones (referred to as tennen toishi[15]) wetted with water, as using oil on such a stone reduces its effectiveness. The geology of Japan provided a type of stone which consists of fine silicate particles in a clay matrix, somewhat softer than novaculite.[16] Besides this clay mineral, some sedimentary rock was used by the Japanese for whetstones, the most famous being typically mined in the Narutaki District just north of Kyoto along the Hon-kuchi Naori stratum.[17] There were many individual mines which produced stone from one of the three stratums in the region, many sought after for specific reputations such as Ohira Uchigumori, Hakka Tomae, and Nakayama stones.[18]

Historically, there are three broad grades of Japanese toishi (sharpening stones): the ara-to, or "rough stone", the naka-to or "middle/medium stone" and the shiage-to or "finishing stone". There is a fourth type of stone, the nagura, which is not used directly. Rather, it is used to form a cutting slurry on the shiage-to (early finishing stone) or awasedo (late finishing stone), which are often too hard to create the necessary slurry. Converting these names to absolute grit size is difficult as the classes are broad and natural stones have no inherent "grit number". As an indication, ara-to is probably (using a non-Japanese system of grading grit size) 500–1000 grit. The naka-to is probably 3000–5000 grit and the shiage-to is likely 7000–10000 grit. Current synthetic grit values range from extremely coarse, such as 120 grit, through extremely fine, such as 30,000 grit (less than half a micrometer abrasive particle size).[citation needed]

Diamond plate

[edit]

A diamond plate is a steel plate, coated with diamond grit, an abrasive that will grind metal. The diamond particles are soldered (electroplated) to the steel substrate.

The plate can be mounted on a plastic or resin base. When mounted, they are sometimes known as diamond stones.[19]

The plate may have a series of holes cut in it that capture the swarf cast off as grinding takes place, and cuts costs by reducing the amount of abrasive surface area on each plate. Diamond plates can serve many purposes including sharpening steel tools, and for maintaining the flatness of man-made waterstones, which can become grooved or hollowed in use. Truing (flattening a stone whose shape has been changed as it wears away) is widely considered essential to the sharpening process but some hand sharpening techniques utilise the high points of a non-true stone. As the only part of a diamond plate to wear away is a very thin coating of grit and adhesive, and in a good diamond plate this wear is minimal due to diamond's hardness, a diamond plate retains its flatness. Rubbing the diamond plate on a whetstone to true (flatten) the whetstone is a modern alternative to more traditional truing methods.[20]

Diamond plates are available in various plate sizes (from credit card to bench plate size) and grades of grit. A coarser grit is used to remove larger amounts of metal more rapidly, such as when forming an edge or restoring a damaged edge. A finer grit is used to remove the scratches of larger grits and to refine an edge. There are two-sided plates with each side coated with a different grit.[21]

Diamond stones are typically coarser than other sharpeners, and are used for the initial stages of knife sharpening. For a knife that has been previously sharpened, this initial diamond stone stage can often be skipped and the re-sharpening begun with a ceramic stone.

Over time diamond stones will wear out and need to be replaced. The lifespan can be extended by using light pressure and allowing the stone to work.

The highest quality diamond sharpeners use monocrystalline diamonds, single structures which will not break, giving them an excellent lifespan. These diamonds are bonded onto a precision ground surface, set in nickel, and electroplated. This process locks the diamonds in place.[21]

Grit size

[edit]There is no dominant standard for the relationship between "grit size" and particle diameter. Part of the difficulty is that "grit size" is used to refer to the smoothness of the finish produced by a sharpening stone, and not just the actual size of the grit particles. Other factors apart from particle diameter that affect the finish (and thus the "grit size" rating) are:

- the shape of the abrasive particles,

- how much of each particle is exposed by the binder,

- friability (whether the abrasive particles can be fractured into smaller ones by the pressure of grinding or polishing),

- the hardness of the abrasive particles, and

- the chemical composition of the abrasive particles (common abrasives include diamond, cubic boron nitride (CBN), chromium(III) oxide, tungsten carbide, silicon carbide and other ceramics).

In synthetic stones, the grit size is related to the mesh size used to select the particles to be included in the abrasive. Sandpaper also uses a similar system.

Here are some typical sharpening stone grit sizes and their uses when sharpening steel knives:

| Grit size | Approximate particle diameter | Typical use[26][27] |

|---|---|---|

| 200 | 80 μm | Establishing an edge; removing chips from a damaged blade. Leaves visible scratches |

| 500 | 30 μm | Roughly sharpening a blunt edge |

| 1000-2000 | 8 μm | Fine, will leave a blade sharper than most factory edges |

| 4,000 | 4 μm | Ultra-fine, for cutting meat |

| 8,000 | 2 μm | Further smoothing a sharp edge for cutting fish or vegetables (sinews in meat will bend an edge this sharp) |

| 10,000 | 0.5 μm | Polishing an edge to a mirror-smooth (but possibly fragile) finish. |

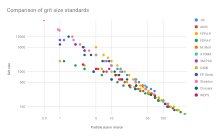

Standards for grit size measurements include JIS, CAMI, ANSI, FEPA-P (for sandpaper), FEPA-F (for metal abrasives), and various trademarked standards for individual company product ranges.

See also

[edit]- Grinding wheel – Abrasive cutting tool for grinders

- Honing steel – Rod of steel used to restore keenness to dulled blades

- Knife sharpening – Process of grinding a knife against a hard surface

- Razor strop – Device for straightening and polishing blades

- Sharpening a scythe – Agricultural reaping hand tool

- Sharpening jig – Tool used to sharpen woodworking tools

References

[edit]- ^ Bates, Robert L.; Jackson, Julia A. (1984-04-11). Dictionary of Geological Terms (3rd ed.). Garden City, N.Y: Anchor. p. 563. ISBN 0-385-18101-9.

- ^ "How to flatten sharpening stones". Wood. May 9, 2017. Retrieved 2022-06-04.

- ^ ""Whet", Dictionary.com". Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ^ "stone | Definition of stone in US English by Oxford Dictionaries". 12 February 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-02-12. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ ""Stoning", Dictionary.com". Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ^ a b "European Natural Stones Collection".

- ^ Leon S. Griswold, The Novaculites of Arkansas in Annual Report of the Geological Survey of Arkansas, Volume 3, 1892, available on Google Books

- ^ "Coticule Belgium Whetstone".

- ^ Ambrose, K et al. (2007). Exploring the Landscape of Charnwood Forest and Mountsorrel. Keyworth, Nottingham: British Geological Survey

- ^ "About Natural Whetstones". Natural Whetstones. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Steve Bottorff, Sharpening Made Easy: A Primer on Sharpening Knives and Other Edged Tools, Knife World Publications, 2002, ISBN 0940362198, pp.29-39

- ^ English, John (2008), Woodworker's Guide to Sharpening: All You Need to Know to Keep Your Tools Sharp, Fox Chapel Publishing, p. 22, ISBN 978-1-56523-309-6.

- ^ "coticule.be". www.coticule.be. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ "Japanese Natural Stones - JNATs".

- ^ David A.Warren, Getting an Edge the Japanese Way, Popular Mechanics, January 1984, pp. 104-107

- ^ "Japanese Natural Stones (JNATS) Glossary & Kanji".

- ^ "Japanese Natural Stone (JNATS) Mines List".

- ^ Thomas Klenck, Tool Test: DMT Diamond Sharpeners, Popular Mechanics, March 1991 pp.62-63

- ^ Miller, Jeff (2012). The Foundations of Better Woodworking: How to use your body, tools and materials to do your best work, Popular Woodworking Books, 2012 ISBN 1440321019, page 120

- ^ a b Diamond sharpening stones wonkeedonkeetrend.co.uk

- ^ "The Grand Unified Grit Chart". bladeforums.com. p. 1. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "The Grand Logarithmic Grit Chart". gritomatic.com. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "Stone, Belt, Paper, Film and Compound Grit Comparison" (PDF). imcclains.com. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "Conversion Chart Abrasives - Grit Sizes". Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "Whetstones: it's all in the grit!". sohoknives. 19 March 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "Sharpening stone grit chart". sharpeningsupplies. Retrieved 3 January 2019.