Stokesosaurus

| Stokesosaurus Temporal range: Late Jurassic (Tithonian), ~

| |

|---|---|

| |

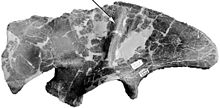

| Holotype UMNH VP 7473 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Tyrannosauroidea |

| Clade: | †Pantyrannosauria |

| Family: | †Stokesosauridae |

| Genus: | †Stokesosaurus Madsen, 1974 |

| Species: | †S. clevelandi

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Stokesosaurus clevelandi Madsen, 1974

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

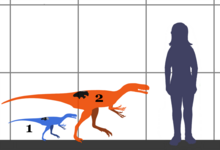

Stokesosaurus (meaning "Stokes' lizard") is a genus of small (around 3 to 4 meters (10 to 13 ft) in length), carnivorous early tyrannosauroid theropod dinosaurs from the late Jurassic period of Utah, United States[1] and Guimarota, Portugal.[2]

History

[edit]

From 1960 onwards Utah geologist William Lee Stokes and his assistant James Henry Madsen excavated thousands of disarticulated Allosaurus bones at the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry in Emery County, Utah. During the early 1970s, Madsen began to catalogue these finds in detail, discovering that some remains represented species new to science. In 1974 Madsen named and described the type species Stokesosaurus clevelandi. Its generic name honours Stokes. The specific name refers to the town of Cleveland, Utah.[3]

The holotype (UMNH 2938, also known as UMNH VP 7473 and formerly known as UUVP 2938) was uncovered in the Brushy Basin Member of the Morrison Formation dating from the early Tithonian stage, about 150 million years old. It consists of a left ilium or hip bone, belonging to a juvenile individual. Madsen also assigned a paratype, UUVP 2320, a 50% larger right ilium. Additionally he referred a right premaxilla, UUVP 2999.[3] However, this was in 2005 referred to Tanycolagreus.[4] Stokesosaurus and Tanycolagreus are about the same size, and it is possible that the latter is a junior synonym of the former. However, the ilium (the best and perhaps only known element of Stokesosaurus) of Tanycolagreus has never been recovered, making direct comparison difficult.[1]

In 1976 Peter Malcolm Galton considered Stokesosaurus to be a second species of the British possible early tyrannosauroid Iliosuchus, that he named as Iliosuchus clevelandi.[5] This has found no acceptance among other researchers;[6] in 1980 Galton himself withdrew his opinion.[7]

Some later finds were referred to Stokesosaurus. This included some ischia and tail vertebrae in 1991,[8] and a partial braincase in 1998.[9] Another, very small ilium referred to Stokesosaurus, found in South Dakota,[10] is lost but may actually belong to the related Aviatyrannis.[11] More fragmentary remains possibly referable to Stokesosaurus have been recovered from stratigraphic zone 2 of the Morrison Formation, dated to the late Kimmeridgian age, about 152 million years ago.[12][13]

A specimen of an indeterminate Stokesosaurus species that was discovered in the Alcobaça Formation of Guimarota, Portugal was identified and described by Rauhut (2000); [2] this specimen was later named as the new genus Aviatyrannis in 2003.[11]

A second species, Stokesosaurus langhami, was described by Roger Benson in 2008 based on a partial skeleton from England.[6] However, further study showed that this species should be referred to a new genus, which was named Juratyrant in 2012. Benson and Stephen Brusatte concluded that not a single bone had been justifiably referred to Stokesosaurus, and that not even the paratype could be safely assigned, leaving the holotype ilium as the only known fossil of the taxon. In addition, many traits initially believed to unite Stokesosaurus clevelandi and Juratyrant langhami under one genus[6] could not be conclusively disproven to exist on other tyrannosauroids. In fact, one of the traits, a posterodorsally inclined ridge on the lateral side of the ilium, was found on the undescribed left ilium of the holotype of Eotyrannus. This leaves only a single autapomorphy of Stokesosaurus which is not present in Juratyrant or other tyrannosauroids: a swollen rim around the articular surface of the pubic peduncle.[14]

The holotype ilium is 22 centimeters (8.7 in) long, indicating a small individual. Madsen in 1974 estimated that the adult body length was about 4 meters (13 ft).[3] In 2010, Gregory S. Paul estimated the length at 2.5 meters (8 ft 2 in) and the weight at 60 kilograms (130 lb).[15]

Classification

[edit]In 1974 Madsen assigned Stokesosaurus to the Tyrannosauridae.[3] However, modern cladistic analyses indicate a more basal position. In 2012 the study by Brusatte and Benson recovered Stokesosaurus as a basal member of the Tyrannosauroidea, and closely related to Eotyrannus and Juratyrant.[14]

Below is a 2013 cladogram by Loewen et al. that places Stokesosaurus and Juratyrant as derived members of Proceratosauridae, due to sharing with Sinotyrannus a narrow preacetabular notch.[16] Many basal tyrannosauroids have incomplete or unknown ilia and this trait may be more widespread than currently known.[14] Various traits support the argument that Sinotyrannus is a proceratosaurid.[16]

However, a 2016 analysis utilizing both parsimonious and Bayesian phylogeny placed Stokesosaurus and Juratyrant as tyrannosauroids slightly more advanced than Proceratosauridae and Dilong. In addition, Eotyrannus is recovered as a sister taxon of these genera in the parsimonious phylogeny.[17]

Paleoecology

[edit]Habitat

[edit]The Morrison Formation is a sequence of shallow marine and alluvial sediments which, according to radiometric dating, ranges between 156.3 million years old (Ma) at its base,[18] to 146.8 million years old at the top,[19] which places it in the late Oxfordian, Kimmeridgian, and early Tithonian stages of the Late Jurassic period. This formation is interpreted as a semiarid environment with distinct wet and dry seasons. The Morrison Basin where dinosaurs lived, stretched from New Mexico to Alberta and Saskatchewan, and was formed when the precursors to the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains started pushing up to the west. The deposits from their east-facing drainage basins were carried by streams and rivers and deposited in swampy lowlands, lakes, river channels and floodplains.[20] This formation is similar in age to the Solnhofen Limestone Formation in Germany and the Tendaguru Formation in Tanzania. In 1877 this formation became the center of the Bone Wars, a fossil-collecting rivalry between early paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope.

Paleofauna

[edit]The Morrison Formation records an environment and time dominated by gigantic sauropod dinosaurs such as Camarasaurus, Barosaurus, Diplodocus, Apatosaurus and Brachiosaurus. Dinosaurs that lived alongside Stokesosaurus included the herbivorous ornithischians Camptosaurus, Dryosaurus, Stegosaurus and Othnielosaurus. Predators in this paleoenvironment included the theropods Saurophaganax, Torvosaurus, Ceratosaurus, Marshosaurus, Ornitholestes and[21] Allosaurus, which accounted for 70 to 75% of theropod specimens and was at the top trophic level of the Morrison food web.[22] Other animals that shared this paleoenvironment included bivalves, snails, ray-finned fishes, frogs, salamanders, turtles, sphenodonts, lizards, terrestrial and aquatic crocodylomorphs, and several species of pterosaur. Examples of early mammals present in this region, were docodonts, multituberculates, symmetrodonts, and triconodonts. The flora of the period has been revealed by fossils of green algae, fungi, mosses, horsetails, cycads, ginkgoes, and several families of conifers. Vegetation varied from river-lining forests of tree ferns, ferns, ginkgos, seed ferns and conifers (gallery forests), to fern savannas with occasional trees such as the Araucaria-like conifer Brachyphyllum.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Foster, J. (2007). Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. 389pp.

- ^ a b Rauhut, O.W.M. (2000). "The dinosaur fauna from the Guimarota mine". In Martin, T.; Krebs, B. (eds.). Guimarota – A Jurassic Ecosystem. München: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. pp. 75–82. ISBN 9783931516802.

- ^ a b c d Madsen, J. H. (1974). "A new theropod dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic of Utah". Journal of Paleontology. 48: 27–31.

- ^ K. Carpenter, C.A. Miles, and K.C. Cloward, 2005, "New small theropod from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Wyoming", In: K. Carpenter (ed.), The Carnivorous Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington pp. 23-48

- ^ Galton, P. M. (1976). "Iliosuchus, a Jurassic dinosaur from Oxfordshire and Utah". Palaeontology. 19: 587–589.

- ^ a b c Benson, R.B.J. (2008). "New information on Stokesosaurus, a tyrannosauroid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from North America and the United Kingdom". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (3): 732–750. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[732:NIOSAT]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 129921557.

- ^ Galton, P.M.; Powell, H.P. (1980). "The ornithischian dinosaur Camptosaurus prestwichii from the Upper Jurassic of England". Palaeontology. 23: 411–443.

- ^ Britt, B (1991). "Theropods of Dry Mesa Quarry (Morrison Formation, Late Jurassic), Colorado, with emphasis on the osteology of Torvosaurus tanneri". Brigham Young University Geology Studies. 37: 1–72.

- ^ Chure, D.; Madsen, James (1998). "An unusual braincase (?Stokesosaurus clevelandi) from the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, Utah (Morrison Formation; Late Jurassic)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (1): 115–125. Bibcode:1998JVPal..18..115C. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011038.

- ^ Foster, J.; Chure, D. (2000). "An ilium of a juvenile Stokesosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic: Kimmeridgian), Meade County, South Dakota". Brigham Young University Geology Studies. 45: 5–10.

- ^ a b Rauhut, Oliver W. M. (2003). "A tyrannosauroid dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic of Portugal". Palaeontology. 46 (5): 903–910. Bibcode:2003Palgy..46..903R. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00325. S2CID 129946607.

- ^ Turner, C.E. and Peterson, F., (1999). "Biostratigraphy of dinosaurs in the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of the Western Interior, U.S.A." Pp. 77–114 in Gillette, D.D. (ed.), Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah. Utah Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication 99-1.

- ^ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327-329.

- ^ a b c Brusatte, S.L.; Benson, R.B.J. (2012). "The systematics of Late Jurassic tyrannosauroids (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from Europe and North America". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0141. hdl:20.500.11820/31f38145-54e7-48f8-819a-262601e93f2b.

- ^ Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press p. 100

- ^ a b Loewen, M.A.; Irmis, R.B.; Sertich, J.J.W.; Currie, P. J.; Sampson, S. D. (2013). Evans, David C (ed.). "Tyrant Dinosaur Evolution Tracks the Rise and Fall of Late Cretaceous Oceans". PLoS ONE. 8 (11): e79420. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...879420L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079420. PMC 3819173. PMID 24223179.

- ^ Brusatte, Stephen L.; Carr, Thomas D. (February 2, 2016). "The phylogeny and evolutionary history of tyrannosauroid dinosaurs". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 20252. Bibcode:2016NatSR...620252B. doi:10.1038/srep20252. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4735739. PMID 26830019.

- ^ Trujillo, K.C.; Chamberlain, K. R.; Strickland, A. (2006). "Oxfordian U/Pb ages from SHRIMP analysis for the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of southeastern Wyoming with implications for biostratigraphic correlations". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 38 (6): 7.

- ^ Bilbey, S.A. (1998). "Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry - age, stratigraphy and depositional environments". In Carpenter, K.; Chure, D.; Kirkland, J.I. (eds.). The Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22. Taylor and Francis Group. pp. 87–120. ISSN 0026-7775.

- ^ Russell, Dale A. (1989). An Odyssey in Time: Dinosaurs of North America. Minocqua, Wisconsin: NorthWord Press. pp. 64–70. ISBN 978-1-55971-038-1.

- ^ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327-329.

- ^ Foster, John R. (2003). Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 23. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. p. 29.

- ^ Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. Vol. 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.