Ground pangolin

| Ground pangolin | |

|---|---|

| |

A ground pangolin in the wilds of Africa

| |

| |

A ground pangolin in defensive posture

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pholidota |

| Family: | Manidae |

| Genus: | Smutsia |

| Species: | S. temminckii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Smutsia temminckii Smuts, 1832[3]

| |

| |

| Ground pangolin range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

synonyms of species:

| |

The ground pangolin (Smutsia temminckii), also known as Temminck's pangolin, Cape pangolin or steppe pangolin is a species of pangolin from genus Smutsia of subfamily Smutsiinae the within family Manidae.[5][1] It is one of four species of pangolins which can be found in Africa, and the only one in southern and eastern Africa. The animal was named for the Dutch zoologist Coenraad Jacob Temminck.

Physical description

[edit]Pangolins are almost completely covered in overlapping, protective scales,[6] which makes up about 20% of their body weight.[7] The scales are composed of keratin, the same material that forms human hair and fingernails,[7] and give pangolins an appearance similar to a pinecone or artichoke.[8] The underside of a pangolin is not covered with scales, but sparse fur, instead. When threatened, it usually rolls up into a ball, thus protecting its vulnerable belly. Pangolins are 30 to 90 cm (1 to 3 feet) long exclusive of the tail and weigh from 5 to 27 kg (10 to 60 pounds). Across all eight species, adult tail length ranges from about 26 to 70 cm (approximately 10 to 28 inches).[9] Mature adults are light brown, olive, and dark brown in color, while young are pale brown or pink in color.

Ground pangolins walk on their hind legs, occasionally using their forelegs and their tail for balance.[10] Their limbs are adapted for digging. They have five toes each with the fore feet having three long, curved claws, which are designed to demolish termite nests and to dig burrows. Because of these claws, pangolins must balance on the outer edges of their fore feet and tuck in the claws to prevent damage. Pangolins have long, broad tails and small, conical heads with jaws that lack teeth. To replace the act of chewing, the pangolin stomach is muscular, with keratinous spines that project into the interior and contains small stones to mash and grind prey, similarly to a bird's gizzard. Pangolins also have long, muscular tongues to reach and lap up ants and termites in cavities. Their tongues stretch so far, they are actually longer than their bodies. The tongue is attached in the lower cavity, near the pelvis and the last pair of ribs, and is able to retract and rest in the chest cavity. Pangolins have reduced pinnae, so they have poor hearing, as well as poor vision, although they do have a strong sense of smell.[6]

Range and distribution

[edit]The African pangolin species are native to 15 African countries dispersed throughout southern, central, and east Africa.[7] S. temminckii is the only species found in southern and eastern Africa. It prefers savannah woodland with moderate amounts of scrub at low elevations.[1]

Behavior and social organization

[edit]Little is known about the pangolin, as it is difficult to study in the wild. Pangolins are solitary animals and only interact for mating. They dig and live in deep burrows made of semispherical chambers. These burrows are large enough for humans to crawl into and stand up. Although it is capable of digging its own burrow, the ground pangolin prefers to occupy those abandoned by warthogs or aardvarks or to lie in dense vegetation, making it even more difficult to observe. African pangolins such as the ground pangolin prefer burrows, while Asian pangolins sleep in hollows and forks of trees and logs. They are nocturnal animals. They mark their territory with urine, secretions, and by scattering their feces. When threatened, their defense mechanism is to curl into a ball with their scales outward, hiss and puff, and lash out with their sharp-edged tails.[6] The scales on the tails are capable of a cutting action to inflict serious wounds.[7] Pangolins are also capable of emitting noxious acid from glands near the anus, similar to a skunk, to ward off predators.[11] The ground pangolin's main predators are leopards, hyenas, and humans.[7] Pangolins roll in herbivore dung.[12] Young pangolins ride on the base of their mothers' tails and slip under the mother when she curls up for protection.

Diet

[edit]The ground pangolin is wholly myrmecophagous, meaning that they only feed on ants and termites.[13] In fact, they demonstrate prey selectivity, only eating specific ant and termite species rather than foraging on the most abundant species.[13] They have been observed exposing entire subterranean nests of a certain species of termites without eating any, preferring to find their species of choice.[14] Their determination of suitable prey does not seem to be based on the size of the species alone, but likely also depends on the chemical and mechanical defenses of each species. Even in arid environments, ground pangolins remain selective in their dietary habits with regard to prey species and only prey on a small subset of available ant and termite species.

Reproduction and lifecycle

[edit]The lifespan of the pangolin is unknown, but the observed lifespan in captivity is 20 years. They are sexually dimorphic, with the males being 10–50% heavier than females.[6] No defined mating season is known, but pangolins tend to mate during the summer and autumn. The gestation period ranges up to 139 days for ground pangolins and other African species. African species females usually birth only one offspring, but litters of three have been observed in Asian species. When born, a pangolin has soft, pale scales, which begin to harden by the second day.[6] The young are usually about 6 in (15 cm) long and about 12 oz (340.19 g) at birth. They are nursed by their mothers for 3 to 4 months, but begin eating termites after only one month.[7] Pangolins reach sexual maturity at 2 years old, when they leave their mothers and begin living alone.[6]

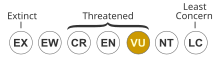

Conservation status and threats

[edit]The ground pangolin is listed as vulnerable by the IUCN Red List. The assessors state, "there is an inferred past/ongoing and projected future population reduction of 30–40% over a 27-year period (nine years past, 18 years future; generation length estimated at nine years) based primarily on ongoing exploitation for traditional medicine and bushmeat throughout the species' range and evidence of increased intercontinental trade to Asia."[1]

The two main threats encountered by ground pangolin populations are habitat loss and illegal trafficking. Due to human cultivation of land, the pangolin faces habitat fragmentation and corresponding reduction in numbers.[6] Meanwhile, illegal trade has an even stronger impact, as pangolins are reported to be the most trafficked animal in the world (with elephants a close second). The scales alone account for 20% of the black market in protected animal parts;[11] they are boiled off the body and used for traditional medicines. Pangolin meat is sold as a high-end delicacy in China and Vietnam, the blood is believed to be a healing tonic, and pangolin fetuses have alleged health benefits and aphrodisiac qualities. A conservative estimate of pangolins trafficked illegally each year is 10,000, while actual numbers for a two-year period may be in excess of 250,000. How many are left in the wild is unknown. Pangolins are generally poorly known to the public and their endangered status has so far received much less publicity than in the case of more iconic species.[8][better source needed]

Phylogeny

[edit]Phylogenetic position of Smutsia temminckii within family Manidae[15][16][17][18]

| Pholidotamorpha |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Pholidota sensu lato)

|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Pietersen, D.; Jansen, R.; Connelly, E. (2019). "Smutsia temminckii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T12765A123585768. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T12765A123585768.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ Smuts, J. (1832.) "Enumerationem Mammalium Capensium", Dessertatio Zoologica Inauguralis. J. C. Cyfveer, Leidae.

- ^ Fitzinger, L. J. (1872.) "Die naturliche familie der schuppenthiere (Manes)." Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Classe, CI., LXV, Abth. I, 9-83.

- ^ Schlitter, D.A. (2005). "Order Pholidota". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 531. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d e f g "What is a Pangolin?"

- ^ a b c d e f African Wildlife Foundation."Pangolin"

- ^ a b John D. Sutter, "The Most Trafficked Animal You Have Never Heard Of" CNN

- ^ "pangolin | Description, Habitat, Diet, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- ^ Stuart, C.; Stuart, M. "Stuarts' Field Guide to Mammals of Southern Africa: Including Angola, Zambia & Malawi" ISBN 9781775841111

- ^ a b Guy Kelly, "Pangolins: 13 facts about the world's most hunted animal"

- ^ Pietersen, Darren W.; Jansen, Raymond; Swart, Jonathan; Panaino, Wendy; Kotze, Antoinette; Rankin, Paul; Nebe, Bruno (2019). "Temminck's pangolin Smutsia temminckii". In Challender, D. W.; Nash, H. C.; Waterman, C. (eds.). Pangolins: Science, Society and Conservation. Academic Press. pp. 187 (175–193). doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-815507-3.00011-3. ISBN 9780128155073. S2CID 213602166.

- ^ a b Swart, J. M. (1999). "Ecological factors affecting the feeding behaviour of pangolins (Manis temminckii)". J. Zool. 247 (3): 281–292. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1999.tb00992.x.

- ^ Pietersen, D. W.; Symes, C. T.; Woodborne, S.; McKechnie, A. E.; Jansen, R. (2016-03-01). "Diet and prey selectivity of the specialist myrmecophage, Temminck's ground pangolin" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 298 (3): 198–208. doi:10.1111/jzo.12302. hdl:2263/52212. ISSN 1469-7998.

- ^ Gaudin, Timothy (2009). "The Phylogeny of Living and Extinct Pangolins (Mammalia, Pholidota) and Associated Taxa: A Morphology Based Analysis" (PDF). Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 16 (4). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Science+Business Media: 235–305. doi:10.1007/s10914-009-9119-9. S2CID 1773698. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-25. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ^ Kondrashov, Peter; Agadjanian, Alexandre K. (2012). "A nearly complete skeleton of Ernanodon (Mammalia, Palaeanodonta) from Mongolia: morphofunctional analysis". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (5): 983–1001. Bibcode:2012JVPal..32..983K. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.694319. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 86059673.

- ^ Philippe Gaubert, Agostinho Antunes, Hao Meng, Lin Miao, Stéphane Peigné, Fabienne Justy, Flobert Njiokou, Sylvain Dufour, Emmanuel Danquah, Jayanthi Alahakoon, Erik Verheyen, William T Stanley, Stephen J O’Brien, Warren E Johnson, Shu-Jin Luo (2018) "The Complete Phylogeny of Pangolins: Scaling Up Resources for the Molecular Tracing of the Most Trafficked Mammals on Earth" Journal of Heredity, Volume 109, Issue 4, Pages 347–359

- ^ Sean P. Heighton, Rémi Allio, Jérôme Murienne, Jordi Salmona, Hao Meng, Céline Scornavacca, Armanda D. S. Bastos, Flobert Njiokou, Darren W. Pietersen, Marie-Ka Tilak, Shu-Jin Luo, Frédéric Delsuc, Philippe Gaubert (2023.) "Pangolin genomes offer key insights and resources for the world’s most trafficked wild mammals"

- IUCN Red List vulnerable species

- Smutsia

- Myrmecophagous mammals

- Mammals of Botswana

- Mammals of Zimbabwe

- Fauna of East Africa

- Mammals described in 1832

- Species that are or were threatened by habitat fragmentation

- Species that are or were threatened by human consumption

- Species that are or were threatened by human consumption for medicinal or magical purposes