St Anne's College, Oxford

| St Anne's College | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Oxford | ||||||||||||||||||||

Wolfson Building, St Anne's College | ||||||||||||||||||||

Arms: Gules, on a chevron between in chief two lions heads erased argent, and in base a sword of the second pummelled and hilt or and enfiled with a wreath of laurel, three ravens, all proper | ||||||||||||||||||||

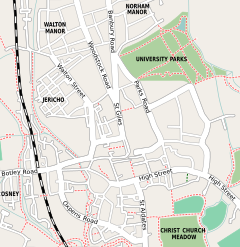

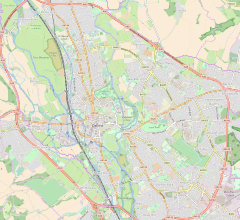

| Location | Woodstock Road and Banbury Road | |||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 51°45′43″N 1°15′42″W / 51.7620°N 1.2617°W | |||||||||||||||||||

| Latin name | Collegium Sanctae Annae | |||||||||||||||||||

| Motto | Consulto et audacter (Purposefully and boldly) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Established | 1879 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Named for | Saint Anne | |||||||||||||||||||

| Previous names | The Society of Oxford Home-Students (1879–1942) The St Anne's Society (1942–1952) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sister college | Murray Edwards College, Cambridge | |||||||||||||||||||

| Principal | Helen King | |||||||||||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 444[1] | |||||||||||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 250[1] | |||||||||||||||||||

| Mascot | Beaver | |||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | |||||||||||||||||||

| Boat club | St Anne's College Boat Club | |||||||||||||||||||

| Map | ||||||||||||||||||||

St Anne's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford[2] in England. It was founded in 1879 and gained full college status in 1959. Originally a women's college, it has admitted men since 1979.[3] It has some 450 undergraduate and 200 graduate students and retains an original aim of allowing women of any financial background to study at Oxford. It still has a student base with a higher than average proportion of female students.[4] The college stands between Woodstock and Banbury roads, next to the University Parks. In April 2017, Helen King, a retired Metropolitan Police Assistant Commissioner, took over as Principal from Tim Gardam.[5][6] Former members include Danny Alexander, Edwina Currie, Ruth Deech, Helen Fielding, William MacAskill, Amanda Pritchard, Simon Rattle, Tina Brown, Mr Hudson and Victor Ubogu.

History

[edit]Society of Oxford Home-Students (1879–1942)

[edit]What is now St Anne's College began as part of the Association for the Education of Women (AEW), the first institution in Oxford with that aim. It then became the Society of Oxford Home-Students.[7] Unlike other women's associations, the society had no fixed site, instead offering lodgings in houses spread across Oxford. This allowed students of various financial backgrounds to study at Oxford, as the cost of accommodation in women's halls was often prohibitive.[7] In the early 20th century, the college housed some students in hostels managed by Catholic and Anglican nuns. Springfield, St Mary was managed by Anglican nuns of the Community of St Mary the Virgin in houses in Banbury Road where they, and other hostels, "had to exercise control over their students according to the rules of the college".[8][9] Other hostels were run by Catholic nuns: the Society of the Sacred Heart in Norham Gardens, the Sisters of Notre Dame in Woodstock Road and the Society of the Holy Child Jesus at Cherwell Edge in St Cross Road.[10] Springfield St Mary was advertised in 1985 in Country Life Magazine as being for sale.[11]

From 1898 till 1906, the Society of Home Students saw some of its members in residence at Wychwood School, then situated at 77 Banbury Road. They were supervised by Miss Margaret Lee who in 1913, was appointed Tutor to the Oxford Home Students, holding this position until she retired in 1936.[12][13][14][15]

Early students of the college included the great-great aunt of Catherine, Princess of Wales. Anglican nun and VAD nurse Gertrude Middleton (1876–1942) lived in college accommodation at Banbury Road having commenced her studies at Oxford in 1900. Her sister Margaret Middleton (1880–1900) was due to study at Oxford alongside her but drowned earlier that year.[16][17][18][19]

The first woman Hon. Lady Secretary of the Association for the Education of Women was Charlotte Green whose husband T.H. Green had also acted as secretary to the association in the 1870s. Her husband having died, Charlotte, a social reformer, resolved to "do what my Husband wanted me to do — to make friends with working people and help them if I could that way".[20] An emphasis on social work saw the Society of Home-Students work with the Lady Margaret Hall Settlement; the Principal of the Society from 1940 to 1953, Eleanor Plumer, had previously been Warden of the Mary Ward Settlement (1923-1927).[21] The Women's University Settlement, Blackfriars Road was partly the result of T.H. Green's "inspiring influence".[22][23][24][25][26]

In 1910, the Society of Oxford Home-Students, with the other women's societies, was recognised by the university. In 1912, the society acquired its first tutors, in German, History and English Literature. In the 1920s, the principals of the women's societies became the first women to receive degrees from the university. The society in the early 1930s still had no centralised site, but within a few years the current location was chosen and by 1937 construction of Hartland House was underway.[7]

St Anne's Society (1942–1952)

[edit]In 1942, the Society of Oxford Home-Students was renamed the St Anne's Society and given its coat of arms by Eleanor Plumer (Principal, 1940–1953).[27] The name St Anne's was chosen as historically, there was a chapel of Saint Anne at the University Church of St Mary the Virgin where, from the college's earliest days, the whole student body would gather for termly services.[28]

St Anne's College (1952 onwards)

[edit]In 1952, the St Anne's Society acquired a royal charter as St Anne's College and in 1959 full college status along with the other women's colleges.[27] The Principal at the time, Mary Ogilvie, pressed for a transition from many disparate dining rooms to a common building. This led to the construction of the dining hall completed in 1959 and visited by Queen Elizabeth II in 1960. Meanwhile student numbers grew to nearly 300, which called for more accommodation and led to the construction of the Wolfson and Rayne buildings in 1964 and 1968. In 1977, the decision was made to become coeducational, with the first male undergraduates matriculating in 1979.[27]

Since then, St Anne's has continued to use female words and pronouns, such as "alumnae" to refer to current and former students. The college explains this: "On 17 June 1979, in the nervous time when the first male Fellows had been elected, and the first male students admitted though they had not yet arrived, a note from the Dean to Governing Body asks hesitantly 'Would Governing Body wish "he" (or "he/she") to be substituted for "she" throughout the College Regulations?' Eventually the question was answered (or perhaps avoided) by a carefully worded statement that remains in the preamble to our Regulations: 'words importing the feminine gender shall include the masculine and vice versa, where the construction so permits and the Regulations do not otherwise expressly provide.'"[29]

In 2023, work began on the full reconstruction of the Bevington Road accommodation blocks, in order to make them more suitable for future generations of students.[30]

The Ship

[edit]The annual magazine for former college members is called The Ship.[31] When still the Society of Oxford Home-Students, the college had its first common room in Ship Street, central Oxford.[7] The Ship started up in about 1910; by the college centenary in 1979 there had been 69 issues.[32] It marked its centenary issue of 2010/2011 with anniversary content.[33]

Location and buildings

[edit]Grounds

[edit]

The college grounds are bounded by Woodstock Road to the west, Banbury Road to the east, and Bevington Road to the north. These grounds house all of the college's administrative and academic buildings, undergraduate accommodation, as well as the hall, which is among the largest in Oxford. The College formerly owned a number of houses throughout Oxford used for undergraduate accommodation, some of which used to be boarding houses of the Society of Oxford Home-Students. Many of these properties were sold off to fund the building of the Ruth Deech Building, completed in 2005.[citation needed]

Accommodation

[edit]St Anne's can accommodate undergraduates on the college site for three years of study. Undergraduates at St Anne's are housed in 14 Victorian houses owned by the college and four purpose-built accommodation blocks. The college also supplies accommodation for some of its graduate students. All undergraduates pay the same amount for their rooms, and every student has access to a communal kitchen in their building.[34]

Victorian houses

[edit]The college uses 1–10 Bevington Road (also known colloquially as "the Bevs"),[35] 58/60 Woodstock Road, and 39/41 Banbury Road (also known as "Above the Bar") as undergraduate accommodation, typically for freshers. The junior (undergraduate) post room is located in 10 Bevington Road, the college laundry in 58/60 Woodstock Road, and the college bar, including a pool room, in 39/41 Banbury Road. Five additional Victorian houses (27/29 and 37 Banbury Road and 48/50 Woodstock Road) hold teaching rooms, seminar rooms, music practice rooms, and college offices.[34] In July 2023, the Bevington Road accommodation began a two-year renovation project. [36]

Rayne and Wolfson Buildings

[edit]

The Rayne and Wolfson Buildings were built in 1964 and are Grade II Listed Buildings virtually identical in design. They house administrative offices on the ground floor and student rooms.[citation needed]

Claire Palley Building

[edit]The Claire Palley Building, completed in 1992 and named after Claire Palley (Principal 1984–1991), was the first accommodation block to have en-suite rooms. It also houses the Mary Ogilvie Lecture Theatre.[citation needed]

Trenaman House

[edit]

Trenaman House, built in 1995, holds student rooms and communal college facilities, including the gym, and since 2008, St Anne's Coffee Shop (STACS). It was named after Nancy Trenaman, sixth Principal of the college (1966–1984).[citation needed]

Ruth Deech Building

[edit]

The Ruth Deech Building, named after the Principal in 1991–2004, was completed in 2005.[37] The lower ground floor has the Tsuzuki lecture theatre, seminar rooms and dining facilities and a new Porter's Lodge on the upper ground floor with 110 en-suite student rooms.[38] One notable feature is a glass lift, the only part of the building to exceed the roof line.[39] The building was awarded the 2007 David Steel sustainable building award by Oxford City Council.[40]

Robert Saunders House

[edit]Robert Saunders House, built in 1996, provides 80 rooms for graduate students in Summertown. It was named after a former bursar of the college, who did much to improve its finances.[citation needed]

Eleanor Plumer House

[edit]Eleanor Plumer House (known until 2008 as 35 Banbury Road) is named after Eleanor Plumer (Principal 1940–1953). It houses the Middle Common Room; facilities include a study area, computer room and kitchen. It also houses some graduate students.[41]

Hartland House

Hartland House, designed by Giles Gilbert Scott, was the first purpose-built college building, finished in 1937 with another wing added in 1973. It houses the old library, the junior and senior common rooms and administrative offices. It features the college crest above the main entrance and engravings of beavers, the college mascot.[citation needed]

Dining Hall

[edit]The Dining Hall, built in 1959, is among the largest in Oxford with a capacity of 300. Three meals are served daily in hall apart from weekends, when only brunch is served. It is also used for college collections (internal college exams) and on occasion college 'bops' (costume parties).[34]

Library

[edit]The college library has over 100,000 volumes, making it one of the largest in Oxford. It is split between the original library in Hartland House and the Tim Gardam building, which opened officially in 2017.[42]

The original college library in Hartland House now houses the law, arts, and humanities collections (Dewey Decimal shelfmarks 340–349 and 700–999).[43]

The new library and academic centre was named after Tim Gardam (principal 2004–2016) and completed in 2016. It is on the site of the former Founders' Gatehouse, which was built in 1966 and was the college lodge until 2005. It covers the area previously taken by the 54 Woodstock Road cottage.[44][45] The centre provides various study and seminar spaces and 1,500 metres of bookshelves for the college's growing book collection. The plans by Fletcher Priest Architects were inspired by Oxford's historic buildings.[46]

The Tim Gardam Building also features two gardens; a roof garden overlooking the dining hall, and a sunken courtyard accessible through the basement.[citation needed]

Traditions

[edit]The college has relatively few traditions and is rare amongst Oxford colleges in not having a chapel, due to its secular outlook. Formal hall is typically held fortnightly. Gowns are not usually worn except for official university occasions such as matriculation and certain college feasts. The college mascot has been a beaver since 1913.[citation needed]

College grace

[edit]The college grace was composed by former classics tutor and founding fellow Margaret Hubbard. It involves the Principal reciting the Latin words Quas decet, (Deo) gratias agamus. Amen. ("For what we have received, we give thanks (to God). Amen.") The inclusion of Deo (to God) depends on whether the grace is religious or secular in nature.[citation needed]

Room ballot

[edit]The college selects accommodation using a room ballot, with the exception of the first years. Those entering their fourth year select their rooms on the first day, followed by third-year rooms on the second day, and second-year rooms on the third and final day. Students are allocated a number within their year denoting their position in the ballot. In first year, this allocation is based on the quality of their previous year's accommodation. In second year, the JCR President, VP and Domestic Affairs Officer pull student numbers from a hat. Students would queue and rooms are allocated one by one. Rooms allocated are crossed off a large board listing all available rooms. Following the Covid-19 pandemic, the room ballot now occurs online, with a spreadsheet denoting available rooms shared with students. There is then a period of one week after the ballot where students can mutually agree on swaps.[citation needed] Unlike many colleges, JCR and MCR committee members receive no advantage in the room ballot for their position.

Sport and societies

[edit]

The college has teams for all major sports and competes in inter-collegiate "Cuppers" tournaments. Fixtures are either played in the neighbouring University Parks, or in the college playing fields on Woodstock Road.[citation needed]

St Anne's College Boat Club (SABC) organises the college's involvement in inter-college rowing events, and the college boathouse, situated on the River Isis in Christ Church Meadow is shared with St Hugh's and Wadham colleges. The college has a joint rugby team with St John's College, which won Cuppers in 2014.[47][48] The women's football team, which is also joint with St John's, was victorious in Cuppers in 2020.[49] Meanwhile, the St Anne's men's football team (known as the Mint Green Army) won the Hassan's Cup plate tournament in 2018.[50]

Notable people

[edit]Former members

[edit]-

Amanda Pritchard, first woman Chief Executive of NHS England

-

Helen Fielding, creator of Bridget Jones

-

Mr Hudson, rapper and R&B artist

-

Sir Simon Rattle, principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic

-

Martha Kearney, journalist and broadcaster

-

Polly Toynbee, journalist and writer

As a former women's college, St Anne's still refers to former students, female or male, as alumnae[29] rather than alumni.

- Sir Danny Alexander (born 1972), Liberal Democrat politician

- Mary Applebey (1916–2012), mental health campaigner and co-founder of MIND

- Karen Armstrong (born 1944), author

- Tina Brown (born 1953), creator of The Daily Beast, former editor of Vanity Fair and The New Yorker

- Rosemary Cramp (born 1929), archaeologist

- Rose Dugdale (born 1941), debutante and convicted terrorist

- Helen Fielding (born 1958), novelist

- Jacob Fortune-Lloyd (born 1988), actor

- Miriam Gross (Lady Owen) (born 1938), journalist, writer and editor

- Fayza Haikal (born 1938), Egyptologist

- Devaki Jain (born 1933), Indian economist and Padma Bhushan awardee

- Diana Wynne Jones (1934–2011), author of Howl's Moving Castle

- Martha Kearney (born 1957), journalist and broadcaster

- Penelope Lively (born 1933), novelist and children's writer

- Benjamin Hudson McIldowie, (born 1979), rapper and R&B artist known by the stage name "Mr Hudson"

- Melanie Phillips (born 1951), journalist and author

- Sir Simon Rattle (born 1955), conductor

- Mary Remnant (1935–2020), early music specialist and performer

- John Robins (born 1982), comedian and radio presenter

- Polly Toynbee (born 1946), journalist and writer

- Victor Ubogu (born 1964), rugby union player

- Jill Paton Walsh (1937–2020), novelist

Academics

[edit]- William MacAskill (born 1987), philosopher and one of the originators of the effective altruism movement

- Peter Ady (1914–2004), economics

- Ruth Deech, Baroness Deech (born 1943), law

- Peter Donnelly (born 1959), mathematics

- Georg Gottlob (born 1956), computer science

- A. C. Grayling (born 1949), philosophy

- Jenifer Hart (1914–2005), politics

- Nancy Hubbard (born 1963), business studies

- Tony Judt (1948–2010), historian

- Iris Murdoch (1919–1999), literature

- Merze Tate (1905–1996), diplomatic historian, first African-American woman student at Oxford University

- Gabriele Taylor (born 1927), philosophy

Gallery

[edit]-

37 Banbury Road, containing offices of fellows of the college

-

The Rayne Building viewed from the quadrangle

-

The Gatehouse, which was demolished in the 2014–15 academic year

-

The rear of Trenaman House viewed from the Bevington Road garden

-

Trenaman House (Upper) containing St Anne's Coffee Shop (STACS) and some undergraduate accommodation

-

Wolfson Building

-

Hartland House in its parkland setting

-

The Pride flag flying over Hartland House in 2023

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Welcome to St Anne's". St Anne's College. 2008. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ^ "St Anne's College | University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ "Statement of Values". About St Anne's College. St Anne's College. 2009. Archived from the original on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ "Undergraduate admissions statistics | University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ "Met assistant commissioner announces retirement – UK Police News – Police Oracle". policeoracle.com.

- ^ "St Anne's College, Oxford". 27 October 2016. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. About the College > Helen King elected as Principal of St Anne's College.

- ^ a b c d "St Anne's History". St Anne's College, Oxford. Archived from the original on 23 August 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Langer, A., ed. (14 June 2021). St Anne's College Alumnae Personal Histories (PDF) (Report). St Anne's College, Oxford. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2022.

- ^ Anson, Peter Frederick (1964). The Call of the Cloister Religious Communities and Kindred Bodies in the Anglican Communion. S.P.C.K. p. 258.

- ^ "St. Anne's College". British History Online. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "Springfield, Banbury Road, Oxford". Country Life. Vol. 178. 1985. p. 1348. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

BANBURY ROAD, OXFORD By order of the Community of St. Mary the Virgin at Wantage.

- ^ "London's National Portrait Gallery – Miss Lee". NPG – London. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

By this time [1896] Margaret had made a plan to take rooms in Oxford for both of them and help Miss [A.S.] Batty to establish a school for girls. This plan was successfully carried out. Margaret and Miss Batty established themselves at 41 Banbury Road and in January I897 a few pupils, daughters of Oxford dons, formed a nucleus of what was later to become Wychwood School. The little school flourished, pupils flocked in, more rooms in the house were added till, in 1898, the lease and later the ownership of 77 Banbury Road were acquired. Miss Batty's health improved marvellously and her wonderful power as a teacher began to be felt. 77 Banbury Road, a charming Regency house with a little garden stretching along North Parade, swarmed with school-children by day, and there were usually a few young women living there while reading for various examinations. The school soon overflowed and moved to Park Crescent in 1906 [shortly thereafter returning to Banbury Road]...To return to Margaret's academic career at Oxford: she held her teaching appointments under the Association for the Education of Women and in 1913 was appointed Tutor to the Oxford Home Students (later St. Anne's College) and she held this until she retired in 1936...MARGARET LUCY LEE was born on 14 July 1871, the eldest child of Thomas William Lee, son of Joseph Lee, of Redbrook House, Flint, and Margaret Anne, daughter of Rev. C. H. Lyon, of Glen Ogil, the seat for 500 years of the cadet branch of the Bowes-Lyons of Glamis Castle.

- ^ Johnson, John de Monins (1908). Religions of the lower culture. Section II. Religions of China and Japan. Section III. Religions of the Egyptians. Section IV. Religions of the Semites. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

Miss Batty, 77 Banbury Road, Oxford – page vi

- ^ Kloester, J. (2013). Georgette Heyer: Biography of a Bestseller. Arrow Books. p. 42. ISBN 9780434020713. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

Later, Carola and Joanna both went to Miss Batty's School for the daughters of Oxford dons (later called the Wychwood School) where they created a ...

- ^ "Archives – St Anne's College, Oxford". St Anne's College, Oxford. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

O.H.S. 1/1. Oxford Home-Students under AEW auspices. Reports 1879–1910 [...Miss G. [Gertrude] Middleton ...member of Society of Oxford Home Students from 1900–1902...[and] lived [during this time] at 77 Banbury Road, Oxford...

- ^ Tominey, Camilla (19 August 2022). "Duchess of Cambridge's great-great aunt was a mental asylum patient – just like Prince William's great-grandmother". UK Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

Historian discovers the couple's relatives lived parallel lives, becoming nuns and working as volunteer nurses during the First World War...Born in 1876, Gertrude was the wealthy sister of the Duchess of Cambridge's great-grandfather Noel Middleton...A brilliant student, Gertrude completed her schooling at age 18 in 1894 in Scotland at the exclusive ladies boarding school St Leonards School in Fife - modelled on Prince William's alma mater Eton. The school was surrounded by the University of St Andrews - where the Cambridges met while studying history of art. Like the Duchess, Gertrude was sporty, playing tennis and lacrosse on the university's playing fields as well as golf on the school's own golf course. Gertrude also played the piano like the Duchess. She continued further study at St Anne's College, Oxford, from 1900-1902 where her first cousin Henry Middleton was studying law at Oxford and could therefore act as her chaperone...Gertrude became a nun at the Anglican Convent of the Epiphany, Truro, Cornwall which had been established by the Bishop of St Andrews, George Wilkinson.

- ^ "Archives – St Anne's College, Oxford". St Anne's College, Oxford. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

O.H.S. 1/1. Oxford Home-Students under AEW auspices. Reports 1879–1910 [...Miss G. [Gertrude] Middleton ...member of Society of Oxford Home Students from 1900–1902...[and] lived [during this time] at 77 Banbury Road, Oxford...

- ^ Thomas, S. "Tragic Loss of Young Photographer in Filey Seaside Incident Sparks Generational Legacy of Photography Among Middletons". TDPel. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

Margaret's Life and Aspirations: Margaret was not just an avid photographer but also a promising young woman who had ambitions of attending Oxford University.

- ^ Joseph, Claudia (2010). Kate: The Making of a Princess. Mainstream Publishing. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

Gertrude was very religious...Filey, where tragedy struck once again...went for a walk along Filey Brigg...Margaret had disappeared...

- ^ "Green [née Symonds], Charlotte Byron (1842–1929), promoter of women's education". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/48416. Retrieved 11 August 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Email from college archivist "In our published history of St Anne’s - https://oac.web.ox.ac.uk/st-annes-college - [Histories - Ruth Florence Butler and M H Prichard, Saint Anne's College: A History (Oxford, Privately Published, 1957) and Marjorie Reeves, St Anne's College, Oxford: An Informal History (Oxford: St Anne's College, 1979)] there are references to the Society of Home-Students working with the Lady Margaret Hall Settlement and the Principal of the Society from 1940 to 1953 (Eleanor Plumer) had previously been Warden of the Mary Ward Settlement (1923-1927)."

- ^ St Hugh's College - Council of St Hugh's College - Miss Rogers, Society of Oxford Home-Students (Tutor)... Miss Dorothy Frances Middleton, Worker at Women's University Settlement, Blackfriars Road. St Hughs College, Oxford. 1912. p. 3, 11, 41. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ "1879 Somerville Hall and The Society of Oxford Home-Students (later St Anne's) were formed. LMH and Somerville received their first students". University of Oxford. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

The Society of Oxford Home-Students (later known as St Anne's) - In 1879, twenty-five women students came under the supervision of the Lady Secretary of the AEW, Charlotte Green, (wife of T.H. Green)...

- ^ Morrow, J. T.H. Green - The Feminism of T.H. Green. Ashgate. p. 479,480,481,482.

The University Women's Settlement founded in Southwark in 1887 proved only one of many ... Green's inspiring influence on the (Women's University) Settlement Movement is well known...

- ^ Holloway, C. (2023). Women and the Anglican Church Congress 1861-1938. Bloomsbury Academic. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ Bush, J. (2007). Women Against the Vote. Oxford University Press. p. 49,50. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

T.H. Green had [in the] 1870s acted as secretary to the Association for the Education of Women, as well as assisting the formation of the Society of Home Students ... [Green had used the model of] the late Victorian settlements which enabled university men and women to help the poor by living amongst them. The success of such ventures owed much to the general expansion of both philanthropy...

- ^ a b c "St Anne's History Brochure" (PDF). st-annes.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

Only in 1959 did the five women's colleges acquire full collegiate status so that their councils became governing bodies and they were, like the men's colleges, fully self-governing.

- ^ "St Anne's College – What's In A Name?". St Anne’s College, Woodstock Road, Oxford, OX2 6HS, UK. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

The Society of Oxford Home-Students had termly services at The University Church of St Mary the Virgin, one of the few opportunities when the whole student body could be gathered together each term. This link may have made the idea of Mary or Mary's mother, Anne, more appealing. Historically there had also been a chapel of St Anne at the University Church.

- ^ a b "St Anne's College, Oxford > Alumnæ & friends> Our alumnæ". st-annes.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ "Bevington Road Regeneration | St Anne's College, Oxford". 4 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ "The Ship". Alumnae & Friends. St Anne's College, Oxford. Archived from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "The Ship". The Ship. St Anne's College. 1979.

- ^ "The Ship". The Ship. St Anne's College. 2011.

- ^ a b c "St Anne's College, Oxford > Living & Studying Here > Accommodation and Meals". st-annes.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "'Last Night in The Bevs' | St Anne's College, Oxford". 14 December 2023. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ "Bevington Road Regeneration | St Anne's College, Oxford". 14 December 2023. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ "St Anne's College Opens New Building" (PDF). Conference Oxford Newsletter. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- ^ "Ruth Deech Building, St Anne's College". AKT II. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Laura Salmi (10 November 2008). "New school meets old school". World Architecture News. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "David Steel Sustainable Buildings Award". Oxford City Council. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Eleanor Plumer House (EPH)". St Anne's College MCR. 12 February 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ "St Anne's College, Oxford > About the College > Library". st-annes.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ White, Clare. "Oxford LibGuides: St Anne's College Library: Home". libguides.bodleian.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "Library and Academic Centre, St Anne's College". ridge.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "St Anne's College, Oxford > Alumnæ & friends > New Library and Academic Centre". st-annes.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "St Anne's College". Fletcher Priest Architects. 2 November 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "Saints Win Cuppers in Dramatic Finale". ourfc.org. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "Saints stun Teddy Hall in last gasp Cuppers victory". Cherwell.org. 11 May 2014.

- ^ "Saints Women's Football Team has won Cuppers for the first time".

- ^ "Anne's dominate the Hassan's Cup". Cherwell.org. 5 March 2018.