STS-47

Spacelab Module LM2 in Endeavour's payload bay, serving as the Spacelab-J laboratory. | |

| Names | Space Transportation System-47 Spacelab-J |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Microgravity research |

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1992-061A |

| SATCAT no. | 22120 |

| Mission duration | 7 days, 22 hours, 30 minutes, 24 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 5,265,523 km (3,271,844 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 126 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Endeavour |

| Launch mass | 117,335 kg (258,679 lb) |

| Landing mass | 99,450 kg (219,250 lb) |

| Payload mass | 12,485 kg (27,525 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 7 |

| Members | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | September 12, 1992, 14:23:00 UTC (10:23 am EDT) |

| Launch site | Kennedy, LC-39B |

| Contractor | Rockwell International |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | September 20, 1992, 12:53:24 UTC (8:53:24 am EDT) |

| Landing site | Kennedy, SLF Runway 33 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric orbit |

| Regime | Low Earth orbit |

| Perigee altitude | 297 km (185 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 310 km (190 mi) |

| Inclination | 57.02° |

| Period | 90.00 minutes |

| Instruments | |

| |

STS-47 mission patch  Back row: Davis, Lee, Gibson, Jemison, Mohri Front row: Apt, Brown | |

STS-47 was NASA's 50th Space Shuttle mission of the program, as well as the second mission of the Space Shuttle Endeavour. The mission mainly involved conducting experiments in life and material sciences inside Spacelab-J, a collaborative laboratory inside the shuttle's payload bay sponsored by NASA and the National Space Development Agency of Japan (NASDA). This mission carried Mamoru Mohri, the first Japanese astronaut aboard the shuttle, Mae Jemison, the first African-American woman to go to space, and the only married couple to fly together on the shuttle, Mark C. Lee and Jan Davis, which had been against NASA policy prior to this mission.

Crew

[edit]| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Fourth spaceflight | |

| Pilot | First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 Flight Engineer |

Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 4 | Only spaceflight | |

| Payload Specialist 1 | First spaceflight | |

As female and male astronauts became more prominently integrated with the shuttle program, NASA enacted an unwritten rule that husband/wife couples would not be assigned to the same mission. However, when Lee and Davis's marriage became known to NASA officials in January 1991, the officials decided to keep the assignment as is, given that both crewmembers already had important roles within the upcoming mission.[1] When asked at a NASA press conference if intimate activities would be taking place on the mission, Davis denied that possibility.[2]

Backup crew

[edit]| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Payload Specialist | ||

| Payload Specialist | ||

| Payload Specialist | ||

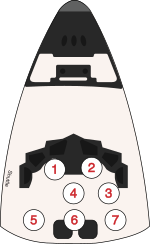

Crew seat assignments

[edit]| Seat[3] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the flight deck. Seats 5–7 are on the mid-deck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gibson | ||

| 2 | Brown | ||

| 3 | Lee | Davis | |

| 4 | Apt | ||

| 5 | Davis | Lee | |

| 6 | Jemison | ||

| 7 | Mohri | ||

Mission highlights

[edit]

At the beginning of September, a problem with an oxygen line in the shuttle's main propulsion system was identified, however, it was resolved without forcing a postponement of the mission.[4]

STS-47 launched from Pad 39B at 10:23:00 a.m. EDT on September 12, 1992, and was the first on-time mission without launch delays since STS-61-B in 1985.[5]

The mission's primary payload was Spacelab-J — a joint mission between NASA and the National Space Development Agency of Japan (NASDA) — which used a crewed Spacelab module to conduct microgravity research in materials and life sciences. Like many previous missions, the international crew was divided into red and blue teams which would work in two 12-hour shifts for around-the-clock operations. Brown, Lee, and Mohri were assigned to the red team, and would conduct experiments while Apt, Davis, and Jemison, assigned to the blue team, would rest, and vice versa. As the mission commander, Gibson was free to work with both teams.[6] Because of the 24-hour schedule, the crew wasn't sent any traditional wake-up calls by mission control.[7]

Spacelab-J included 24 experiments in materials science and 20 life sciences experiments, the majority of which were sponsored by NASDA and NASA, while 2 were sponsored by collaborative civilian efforts.[8] The Payload Crew Training Manager was Homer Hickam, who also worked during the mission as a Crew Interface Coordinator to talk to the crew during their science experiments and relay any concerns from the scientists on the ground.[9]

Materials science investigations covered such fields as biotechnology, electronic materials, fluid dynamics and transport phenomena, glass and ceramics, metals and alloys, and acceleration measurements. Life sciences included experiments on human health, cell separation and biology, developmental biology, animal and human physiology and behavior, space radiation, and biological rhythms. Test subjects included the crew, Japanese koi fish (carp), cultured animal and plant cells, chicken embryos, fruit flies, fungi, plant seeds, frogs and frog eggs, and oriental hornets.[8]

Jemison and Japanese astronaut Mamoru Mohri were trained to use the Autogenic Feedback Training Exercise (AFTE),[10] a technique developed by Patricia S. Cowings that uses biofeedback and autogenic training to help patients monitor and control their physiology as a possible treatment for motion sickness, anxiety and stress-related disorders.[11][12]

Aboard the Spacelab Japan module, Jemison tested NASA's Fluid Therapy System, a set of procedures and equipment to produce water for injection, developed by Sterimatics Corporation. She then used IV bags and a mixing method, developed by Baxter Healthcare, to use the water from the previous step to produce saline solution in space.[13] Jemison was also a co-investigator of two bone cell research experiments.[14] Another experiment she participated in was to induce female frogs to ovulate, fertilize the eggs, and then see how tadpoles developed in zero gravity.[15]

Secondary Experiments

[edit]On the middeck, a variety of experiments were conducted, including the Israel Space Agency Investigation About Hornets (ISAIAH), the Solid Surface Combustion Experiment (SSCE), and the Shuttle Amateur Radio Experiment (SAREX II).[16]: 4 External experiments using the Ultraviolet Plume Imager (UVPI) on the LACE satellite and observations at the Air Force Maui Optical Station (AMOS) were also conducted while Endeavour was in orbit.[8]

ISAIAH was the first microgravity experiment flown for the Israel Space Agency (ISA). Originating from Tel-Aviv University, it was intended to observe the effects of microgravity on oriental hornets and their ability to build combs in zero-g.[16]: 28 However, a failure in the water system resulted in an unexpected rise of the humidity level in the experiment, which resulted in the deaths of 202 out of the 230 hornets and 103 pupae out of the 120 in the experiment. While some of the hornets in the bottom container of the experiment remained active through flight day 7, no new nests were created until after the mission's completion, and the average lifespan of the hornets that flew into space was considerably less than that of the control group. None of the hornet pupae that flew into space metamorphized.[17][18]

Twelve Get Away Special (GAS) canisters (10 with experiments, 2 with ballast) were carried in the payload bay. Among the GAS canisters was G-102, sponsored by the Boy Scouts of America's Exploring Division in cooperation with the TRW Systems Integration Group, Fairfax, Virginia. The project was named Project POSTAR and was the first space experiment created entirely by members of the Boy Scouts of America.[16][19]

Also on board were two experiments prepared by Ashford School of Art & Design in Kent, United Kingdom, which, at the time, was a girls-only school.[16] The school had won a competition run by Independent Television News. The experiments were contained in G-520. The first one injected a few grams of cobalt nitrate crystals to a sodium silicate to create a chemical garden in weightless condition. The growths, which were photographed 66 times as they developed, spread out in random directions, twisted, and, in some cases, formed spirals. A second experiment to investigate how Liesegang rings formed in space failed to operate correctly due to friction in parts of the mechanism. On its return, the experiment was exhibited in the London Science Museum.[20]

While in orbit, Jemison planned to speak from orbit on a live TV conference to Chicago grade-school students at an event hosted by NASA and the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. The event was planned for September 16, 1992, at 7:00 p.m. central time.[21]

The mission, scheduled to end on September 19, 1992, was extended for one more day to complete certain experiments.[22]

Gallery

[edit]-

Launch of STS-47

-

STS-47 crew pose for a portrait inside the Spacelab-J module during the mission.

-

Eye of Hurricane Bonnie (1992) photographed onboard Endeavour.

-

Alternate crew and support staff photo, featuring the seven crewmembers and spacesuit technician Sharon McDougle, front center, among others.

See also

[edit]- List of human spaceflights

- List of Space Shuttle missions

- Nikon NASA F4

- Spacelab

- Outline of space science

- Project POSTAR

- Space Shuttle

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ^ "Married astronauts can fly together, NASA says". United Press International. Johnson Space Center, Houston: UPI Archives. March 6, 1991. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "Shuttle couple ready for launch in September". Tampa Bay Times. Times Publishing Company. June 13, 1992. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

At a news conference Wednesday in Huntsville, Davis answered "no" when asked if there would be sexual experiments on the seven-day mission.

- ^ "STS-47". Spacefacts. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ "Shuttle launch set for September 12 but problem exists". Defense Daily. Vol. 172, no. 44. Access Intelligence, LLC. September 2, 1992. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Dumoulin, Jim (June 29, 2001). "STS-47". Kennedy Space Center Science, Technology and Engineering. NASA/KSC Information Technology Directorate. Archived from the original on January 28, 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Evans, Ben (October 28, 2012). "Of Marriage, Medaka Fish and Multiculturalism: The Legacy of STS-47". America Space. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ Fries, Colin (March 13, 2015). "Chronology of Wakeup Calls" (PDF). NASA History Division. p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 3, 2024. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ a b c Ryba, Jeanne (ed.). "STS-47". NASA. Archived from the original on May 14, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "'October Sky' high". Florida Today. March 29, 1999. Retrieved February 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

Most of my work was with Spacelab flight, especially Spacelab J

- ^ Cowings, Patricia (Summer 2003). "NASA Contributes to Improving Health". NASA Innovation. 11 (2). Archived from the original on October 4, 2011. Retrieved September 14, 2011.

- ^ Steiner, Victoria (January 7, 2003). "NASA Commercializes Method For Health Improvement". NASA Ames Research Center. Archived from the original on June 26, 2017. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Bugos, Glenn E. (2014). "Atmosphere of Freedom: 75 Years at the NASA Ames Research Center" (PDF). NASA Ames Research Center. pp. 159–61. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Miller, Fletcher; Niederhaus, Charles; Barlow, Karen; Griffin, DeVon (January 8, 2007). "Intravenous Solutions for Exploration Missions" (PDF). 45th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit. Reno, Nevada: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. doi:10.2514/6.2007-544. hdl:2060/20070018153. ISBN 978-1-62410-012-3. S2CID 4692452.

- ^ Greene, Nick (October 17, 1956). "Dr. Mae C. Jemison: Astronaut and Visionary". ThoughtCo. Dotdash. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved September 14, 2011.

- ^ Dunn, Marcia (September 8, 1992). "1st Black Woman in Space Taking One Small Step for Equality". The Titusville Herald. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Orloff, Richard W., ed. (January 2001) [September 1992]. "Space Shuttle Mission STS-47 – Press Kit" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 27, 2023. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ Fricke, Robert W. (October 1, 1992). STS-47 Space Shuttle Mission Report (PDF) (Report). Houston, Texas: Lockheed Engineering and Sciences Company – National Aeronautics and Space Administration. p. 22. 19930016771. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ "IAMI – Projects". IAMI. Israel Aerospace Medicine Institute. Archived from the original on December 3, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Evans, Ben (2014). Partnership in Space: The Mid to Late Nineties. New York: Springer Praxis Books. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-4614-3278-4. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ "Late bloom for crystal garden". The New Scientist. January 2, 1993. Archived from the original on March 9, 2010. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- ^ Carr, Jeffrey (September 14, 1992). "Astronaut Mae Jemison to Speak with Chicago Youth" (PDF) (Press release). Houston: NASA. p. 120. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 2, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ "1981-1999 Space Shuttle Mission Chronology" (PDF). NASA. p. 26. Retrieved January 29, 2022.