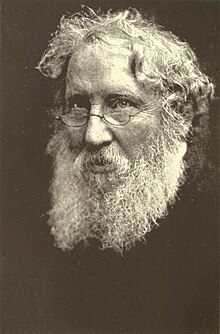

Solomon Schechter

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

Rabbi Solomon Schechter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal life | |

| Born | 7 December 1847 |

| Died | 19 November 1915 (aged 67) New York City, US |

| Nationality | Moldavian (until 1859) Romanian (after 1881) British American |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna, Humboldt University of Berlin |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Judaism |

Solomon Schechter (Hebrew: שניאור זלמן הכהן שכטר; 7 December 1847 – 19 November 1915) was a Moldavian-born British-American rabbi, academic scholar and educator, most famous for his roles as founder and President of the United Synagogue of America, President of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, and architect of American Conservative Judaism.

Early life

[edit]He was born in Focşani, Moldavia (now Romania), to Rabbi Yitzchok Hakohen, a shochet ("ritual slaughterer") and member of Chabad hasidim. He was named after its founder, Shneur Zalman of Liadi. Schechter received his early education from his father. Reportedly, he learned to read Hebrew by age 3, and by 5 mastered Chumash. He went to a yeshiva in Piatra Neamț at age 10 and at age thirteen studied with one of the major Talmudic scholars, Rabbi Joseph Saul Nathanson of Lemberg.[1] In his 20s, he went to the Rabbinical College in Vienna, where he studied under the more modern Talmudic scholar Meir Friedmann, before moving on in 1879 to undertake further studies at the Berlin Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums and at the University of Berlin. In 1882, he was invited to Britain, to be tutor of rabbinics under Claude Montefiore in London.

Academic career

[edit]In 1890, after the death of Solomon Marcus Schiller-Szinessy, he was appointed to the faculty at Cambridge University, serving as a lecturer in Talmudics and reader in Rabbinics.[2] The students of the Cambridge University Jewish Society hold an annual Solomon Schechter Memorial Lecture.

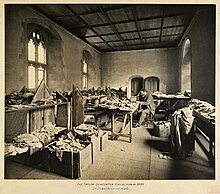

His greatest academic fame came from his excavation in 1896 of the papers of the Cairo Geniza, an extraordinary collection of over 100,000 pages (around 300,000 documents) of rare Hebrew religious manuscripts and medieval Jewish texts that were preserved at an Egyptian synagogue. The find revolutionized the study of Medieval Judaism.

Jacob Saphir was the first Jewish researcher to recognize the significance of the Cairo Geniza, as well as the first to publicize the existence of the Midrash ha-Gadol. Schechter was alerted to the existence of the Geniza's papers in May 1896 by two Scottish sisters, Agnes and Margaret Smith (also known as Mrs. Lewis and Mrs. Gibson), who showed him some leaves from the Geniza that contained the Hebrew text of Sirach, which had for centuries only been known in Greek and Latin translation.[3] Letters, written at Schechter's prompting, by Agnes Smith to The Athenaeum and The Academy quickly revealed the existence of another nine leaves of the same manuscript in the possession of Archibald Sayce at University of Oxford.[4] Schechter quickly found support for another expedition to the Cairo Geniza, and arrived there in December 1896 with an introduction from the Chief Rabbi, Hermann Adler, to the Chief Rabbi of Cairo, Aaron Raphael Ben Shim'on.[5] He carefully selected for the Cambridge University Library a trove three times the size of any other collection: this is now part of the Taylor-Schechter Collection. The find was instrumental in Schechter resolving a dispute with David Margoliouth as to the likely Hebrew language origins of Sirach.[6]

Charles Taylor took a great interest in Solomon Schechter's work in Cairo, and the genizah fragments presented to the University of Cambridge are known as the Taylor-Schechter Collection.[7] He was joint editor with Schechter of The Wisdom of Ben Sira, 1899. He published separately Cairo Genizah Palimpsests, 1900.

He became a Professor of Hebrew at University College London in 1899 and remained until 1902 when he moved to the United States and was replaced by Israel Abrahams.

American Jewish community

[edit]In 1902, traditional Jews reacting against the progress of the American Reform Judaism movement, which was trying to establish an authoritative "synod" of American rabbis, recruited Schechter to become President of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTSA).

Schechter served as the second President of the JTSA, from 1902 to 1915, during which time he founded the United Synagogue of America, later renamed as the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism.

Death

[edit]He died in 1915, and was buried at Mount Hebron Cemetery in Flushing, Queens. [8]

Religious and cultural beliefs

[edit]Schechter emphasized the centrality of Jewish law (Halakha) in Jewish life in a speech in his inaugural address as President of the JTSA in 1902:

- "Judaism is not a religion which does not oppose itself to anything in particular. Judaism is opposed to any number of things and says distinctly "thou shalt not." It permeates the whole of your life. It demands control over all of your actions, and interferes even with your menu. It sanctifies the seasons, and regulates your history, both in the past and in the future. Above all, it teaches that disobedience is the strength of sin. It insists upon the observance of both the spirit and of the letter; spirit without letter belongs to the species known to the mystics as "nude souls" (nishmatim artilain), wandering about in the universe without balance and without consistency...In a word, Judaism is absolutely incompatible with the abandonment of the Torah."

Schechter, on the other hand, believed in what he termed "Catholic Israel." The basic idea being that Jewish law, Halacha, is formed and evolves based on the behavior of the people. This concept of modifying the law based on national consensus is an untraditional viewpoint.

Schechter was an early advocate of Zionism. He was the chairman of the committee that edited the Jewish Publication Society of America Version of the Hebrew Bible.

Legacy

[edit]

Schechter's name is synonymous with the findings of the Cairo Geniza. He placed the JTSA on an institutional footing strong enough to endure for over a century. He became identified as the foremost personality of Conservative Judaism and is regarded as its founder. A network of Conservative Jewish day schools is named in his honor, as well as a summer camp in Olympia, Washington. There are several dozen Solomon Schechter Day Schools across the United States and Canada.

His daughter Ruth was married to the South African Jewish politician Morris Alexander from 1907 to 1935.[9]

Bibliography

[edit]- Schechter, Solomon (1896) Studies in Judaism. 3 vols. London: A. & C. Black, 1896-1924 (Ser. III published by The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia PA)

- Schechter, Solomon (1909) Some Aspects of Rabbinic Theology London: A. and C. Black (Reissued by Schocken Books, New York, 1961; again by Jewish Lights, Woodstock, Vt., 1993: including the original preface of 1909 & the introduction by Louis Finkelstein; new introduction by Neil Gilman [i.e. Gillman])

References

[edit]- ^ Librarian's Lobby October 2000 Heroes of learning Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine at home.earthlink.net

- ^ "Schechter, Salomon (SCCR892S)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Soskice, Janet (2010) Sisters of Sinai. London: Vintage, 239–40

- ^ Soskice, Janet (2010). Sisters of Sinai. London: Vintage. pp. 241–2.

- ^ Soskice, Janet (2010) Sisters of Sinai. London: Vintage, 246

- ^ Soskice, Janet (2010) Sisters of Sinai. London: Vintage, 240–41

- ^ "Taylor-Schechter: a Priceless Collection". lib.cam.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 7 July 2009. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ "Dr. Schechter Dead; Noted As A Scholar – President of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America Stricken While Lecturing – His Career Ended at 67 – A Foremost Theologian of His Race and Famous for His Discoveries in Hebrew Literature". New York Times. 20 November 1915. p. 15. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Abrahams, Israel (1968). "Alexander, Morris". In De Kock, W. J. (ed.). Dictionary of South African Biography. Vol. 1 (1st ed.). p. 11. OCLC 85921202.

Further reading

[edit]- Cohen, Michael R. (2012). The Birth of Conservative Judaism: Solomon Schechter's Disciples and the Creation of an American Religious Movement. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-52677-7.

- Fine, David J. (1997). "Solomon Schechter and the Ambivalence of Jewish Wissenschaft". Judaism. 46 (181): 3–24. ISSN 0022-5762.

- Gillman, Neil (1993). Conservative Judaism: the New Century. West Orange: Behrman House. ISBN 0-87441-547-0.

- Hoffman, Adina; Cole, Peter (2011). Sacred Trash: the lost and found world of the Cairo Geniza. New York: Schocken. ISBN 978-0-8052-4258-4.

- Starr, David (2003). Catholic Israel: Solomon Schechter, Unity and Fragmentation in Modern Jewish History. PhD Dissertation, Columbia University.

External links

[edit]- Solomon Schechter, from Neil Gillman's book on Conservative Judaism

- Biography at the Jewish Virtual Library

- Louis Jacobs, From Cairo to Catholic Israel: Solomon Schechter, in The Jewish Religion: a Companion, OUP, 1995

- Solomon Schechter Collection at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

- Solomon Schechter School of Greater Boston

- AHRC Rylands Cairo Genizah Project[permanent dead link]

- Solomon Schechter School of Queens

- Solomon Schechter School of Westchester Archived 4 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- 1847 births

- 1915 deaths

- 19th-century British rabbis

- 19th-century Romanian rabbis

- 20th-century British rabbis

- 20th-century Romanian rabbis

- American Conservative rabbis

- American male non-fiction writers

- American Zionists

- Conservative Zionist rabbis

- Jews from the Principality of Moldavia

- Kohanim writers of Rabbinic literature

- Academics of University College London

- Academics of the University of Cambridge

- Jewish American academics

- Jewish American non-fiction writers

- Jewish scholars

- Jewish Theological Seminary of America faculty

- Jewish Egyptian history

- American people of Romanian-Jewish descent

- Romanian Zionists

- British Zionists

- British people of Romanian-Jewish descent

- People from Focșani

- Romanian emigrants to the United States

- 20th-century American rabbis

- 19th-century American rabbis

- Burials at Mount Hebron Cemetery (New York City)

- Jewish translators of the Bible

- Humboldt University of Berlin alumni