Sociology of the Internet

| Part of a series on |

| Sociology |

|---|

|

| Internet |

|---|

|

|

|

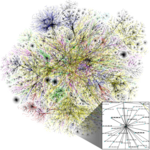

The sociology of the Internet (or the social psychology of the internet) involves the application of sociological or social psychological theory and method to the Internet as a source of information and communication. The overlapping field of digital sociology focuses on understanding the use of digital media as part of everyday life, and how these various technologies contribute to patterns of human behavior, social relationships, and concepts of the self. Sociologists are concerned with the social implications of the technology; new social networks, virtual communities and ways of interaction that have arisen, as well as issues related to cyber crime.

The Internet—the newest in a series of major information breakthroughs—is of interest for sociologists in various ways: as a tool for research, for example, in using online questionnaires instead of paper ones, as a discussion platform, and as a research topic. The sociology of the Internet in the stricter sense concerns the analysis of online communities (e.g. as found in newsgroups), virtual communities and virtual worlds, organizational change catalyzed through new media such as the Internet, and social change at-large in the transformation from industrial to informational society (or to information society). Online communities can be studied statistically through network analysis and at the same time interpreted qualitatively, such as through virtual ethnography. Social change can be studied through statistical demographics or through the interpretation of changing messages and symbols in online media studies.

Emergence of the discipline

[edit]The Internet is a relatively new phenomenon. As Robert Darnton wrote, it is a revolutionary change that "took place yesterday, or the day before, depending on how you measure it."[1] The Internet developed from the ARPANET, dating back to 1969; as a term it was coined in 1974. The World Wide Web as we know it was shaped in the mid-1990s, when graphical interface and services like email became popular and reached wider (non-scientific and non-military) audiences and commerce.[1][2] Internet Explorer was first released in 1995; Netscape a year earlier. Google was founded in 1998.[1][2] Wikipedia was founded in 2001. Facebook, MySpace, and YouTube in the mid-2000s. Web 2.0 is still emerging. The amount of information available on the net and the number of Internet users worldwide has continued to grow rapidly.[2] The term 'digital sociology' is now becoming increasingly used to denote new directions in sociological research into digital technologies since Web 2.0.

Digital sociology

[edit]The first scholarly article to have the term digital sociology in the title appeared in 2009.[3] The author reflects on the ways in which digital technologies may influence both sociological research and teaching. In 2010, 'digital sociology' was described, by Richard Neal, in terms of bridging the growing academic focus with the increasing interest from global business.[4] It was not until 2013 that the first purely academic book tackling the subject of 'digital sociology' was published.[5] The first sole-authored book entitled Digital Sociology was published in 2015,[6] and the first academic conference on "Digital Sociology" was held in New York, NY in the same year.[7]

Although the term digital sociology has not yet fully entered the cultural lexicon, sociologists have engaged in research related to the Internet since its inception. These sociologists have addressed many social issues relating to online communities, cyberspace and cyber-identities. This and similar research has attracted many different names such as cyber-sociology, the sociology of the internet, the sociology of online communities, the sociology of social media, the sociology of cyberculture, or something else again.

Digital sociology differs from these terms in that it is wider in its scope, addressing not only the Internet or cyberculture but also the impact of the other digital media and devices that have emerged since the first decade of the twenty-first century. Since the Internet has become more pervasive and linked with everyday life, references to the 'cyber' in the social sciences seems now to have been replaced by the 'digital'. 'Digital sociology' is related to other sub-disciplines such as digital humanities and digital anthropology. It is beginning to supersede and incorporate the other titles above, as well as including the newest Web 2.0 digital technologies into its purview, such as wearable technology, augmented reality, smart objects, the Internet of Things and big data.

Research trends

[edit]According to DiMaggio et al. (1999),[2] research tends to focus on the Internet's implications in five domains:

- inequality (the issues of digital divide)

- public and social capital (the issues of date displacement)

- political participation (the issues of public sphere, deliberative democracy and civil society)

- organizations and other economic institutions

- participatory culture and cultural diversity

Early on, there were predictions that the Internet would change everything (or nothing); over time, however, a consensus emerged that the Internet, at least in the current phase of development, complements rather than displaces previously implemented media.[2] This has meant a rethinking of the 1990s ideas of "convergence of new and old media". Further, the Internet offers a rare opportunity to study changes caused by the newly emerged—and likely, still evolving—information and communication technology (ICT).[2]

Social impact

[edit]The Internet has created social network services, forums of social interaction and social relations, such as Facebook, MySpace, Meetup, and CouchSurfing which facilitate both online and offline interaction.

Though virtual communities were once thought to be composed of strictly virtual social ties, researchers often find that even those social ties formed in virtual spaces are often maintained both online and offline[8][9]

There are ongoing debates about the impact of the Internet on strong and weak ties, whether the Internet is creating more or less social capital,[10][11] the Internet's role in trends towards social isolation,[12] and whether it creates a more or less diverse social environment.

It is often said the Internet is a new frontier, and there is a line of argument to the effect that social interaction, cooperation and conflict among users resembles the anarchistic and violent American frontier of the early 19th century.[13]

In March 2014, researchers from the Benedictine University at Mesa in Arizona studied how online interactions affect face-to-face meetings. The study is titled, "Face to Face Versus Facebook: Does Exposure to Social Networking Web Sites Augment or Attenuate Physiological Arousal Among the Socially Anxious," published in Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking.[14] They analyzed 26 female students with electrodes to measure social anxiety. Prior to meeting people, the students were shown pictures of the subject they were expected to meet. Researchers found that meeting someone face-to-face after looking at their photos increases arousal, which the study linked to an increase in social anxiety. These findings confirm previous studies that found that socially anxious people prefer online interactions. The study also recognized that the stimulated arousal can be associated with positive emotions and could lead to positive feelings.

Recent research has taken the Internet of Things within its purview, as global networks of interconnected everyday objects are said to be the next step in technological advancement.[15] Certainly, global space- and earth-based networks are expanding coverage of the IoT at a fast pace. This has a wide variety of consequences, with current applications in the health, agriculture, traffic and retail fields.[16] Companies such as Samsung and Sigfox have invested heavily in said networks, and their social impact will have to be measured accordingly, with some sociologists suggesting the formation of socio-technical networks of humans and technical systems.[17][18] Issues of privacy, right to information, legislation and content creation will come into public scrutiny in light of these technological changes.[16][19]

Digital Sociology and Data Emotions

[edit]Digital sociology is connected with data and data emotions[20] Data emotions happens when people use digital technologies that can effect their decision-making skills or emotions. Social media platforms collects users data while also effecting their emotional state of mind, which causes either solidarity or social engagement amongst users. Social media platforms such as Instagram and Twitter can evoke emotions of love, affection, and empathy. Viral challenges such as the 2014 Ice Bucket Challenge[20] and viral memes has brought people together through mass participation displaying cultural knowledge and understanding of self. Mass participation in viral events prompts users to spread information (data) to one another effecting psychological state of mind and emotions. The link between digital sociology and data emotions is formed through the integration of technological devices within everyday life and activities.

The impact on children

[edit]

Researchers have investigated the use of technology (as opposed to the Internet) by children and how it can be used excessively, where it can cause medical health and psychological issues.[21] The use of technological devices by children can cause them to become addicted to them and can lead them to experience negative effects such as depression, attention problems, loneliness, anxiety, aggression and solitude.[21] Obesity is another result from the use of technology by children, due to how children may prefer to use their technological devices rather than doing any form of physical activity.[22] Parents can take control and implement restrictions to the use of technological devices by their children, which will decrease the negative results technology can have if it is prioritized as well as help put a limit to it being used excessively.[22]

Children can use technology to enhance their learning skills - for example: using online programs to improve the way they learn how to read or do math. The resources technology provides for children may enhance their skills, but children should be cautious of what they get themselves into due to how cyber bullying may occur. Cyber bullying can cause academic and psychological effects due to how children are suppressed by people who bully them through the Internet.[23] When technology is introduced to children they are not forced to accept it, but instead children are permitted to have an input on what they feel about either deciding to use their technological device or not.[24][need quotation to verify] . The routines of children have changed due to the increasing popularity of internet connected devices, with Social Policy researcher Janet Heaton concluding that, "while the children's health and quality of life benefited from the technology, the time demands of the care routines and lack of compatibility with other social and institutional timeframes had some negative implications".[25] Children's frequent use of technology commonly leads to decreased time available to pursue meaningful friendships, hobbies and potential career options.

While technology can have negative impacts on the lives of children, it can also be used as a valuable learning tool that can encourage cognitive, linguistic and social development. In a 2010 study by the University of New Hampshire, children that used technological devices exhibited greater improvements in problem-solving, intelligence, language skills and structural knowledge in comparison to those children who did not incorporate the use of technology in their learning.[26] In a 1999 paper, it was concluded that "studies did find improvements in student scores on tests closely related to material covered in computer-assisted instructional packages", which demonstrates how technology can have positive influences on children by improving their learning capabilities.[27] Problems have arisen between children and their parents as well when parents limit what children can use their technological devices for, specifically what they can and cannot watch on their devices, making children frustrated.[28]

Political organization and censorship

[edit]The Internet has achieved new relevance as a political tool. The presidential campaign of Howard Dean in 2004 in the United States became famous for its ability to generate donations via the Internet, and the 2008 campaign of Barack Obama became even more so. Increasingly, social movements and other organizations use the Internet to carry out both traditional and the new Internet activism.

Some governments are also getting online. Some countries, such as those of Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Myanmar, the People's Republic of China, and Saudi Arabia use filtering and censoring software to restrict what people in their countries can access on the Internet. In the United Kingdom, they also use software to locate and arrest various individuals they perceive as a threat. Other countries including the United States, have enacted laws making the possession or distribution of certain material such as child pornography illegal but do not use filtering software. In some countries Internet service providers have agreed to restrict access to sites listed by police.

Economics

[edit]While much has been written of the economic advantages of Internet-enabled commerce, there is also evidence that some aspects of the Internet such as maps and location-aware services may serve to reinforce economic inequality and the digital divide.[29] Electronic commerce may be responsible for consolidation and the decline of mom-and-pop, brick and mortar businesses resulting in increases in income inequality.[30]

Philanthropy

[edit]The spread of low-cost Internet access in developing countries has opened up new possibilities for peer-to-peer charities, which allow individuals to contribute small amounts to charitable projects for other individuals. Websites such as Donors Choose and Global Giving now allow small-scale donors to direct funds to individual projects of their choice.

A popular twist on Internet-based philanthropy is the use of peer-to-peer lending for charitable purposes. Kiva pioneered this concept in 2005, offering the first web-based service to publish individual loan profiles for funding. Kiva raises funds for local intermediary microfinance organizations which post stories and updates on behalf of the borrowers. Lenders can contribute as little as $25 to loans of their choice, and receive their money back as borrowers repay. Kiva falls short of being a pure peer-to-peer charity, in that loans are disbursed prior being funded by lenders and borrowers do not communicate with lenders themselves.[31][32] However, the recent spread of cheap Internet access in developing countries has made genuine peer-to-peer connections increasingly feasible. In 2009 the US-based nonprofit Zidisha tapped into this trend to offer the first peer-to-peer microlending platform to link lenders and borrowers across international borders without local intermediaries. Inspired by interactive websites such as Facebook and eBay, Zidisha's microlending platform facilitates direct dialogue between lenders and borrowers and a performance rating system for borrowers. Web users worldwide can fund loans for as little as a dollar.[33]

Leisure

[edit]The Internet has been a major source of leisure since before the World Wide Web, with entertaining social experiments such as MUDs and MOOs being conducted on university servers, and humor-related Usenet groups receiving much of the main traffic. Today, many Internet forums have sections devoted to games and funny videos; short cartoons in the form of Flash movies are also popular. Over 6 million people use blogs or message boards as a means of communication and for the sharing of ideas.

The pornography and gambling industries have both taken full advantage of the World Wide Web, and often provide a significant source of advertising revenue for other websites. Although governments have made attempts to censor Internet porn, Internet service providers have told governments that these plans are not feasible.[34] Also many governments have attempted to put restrictions on both industries' use of the Internet, this has generally failed to stop their widespread popularity.

One area of leisure on the Internet is online gaming. This form of leisure creates communities, bringing people of all ages and origins to enjoy the fast-paced world of multiplayer games. These range from MMORPG to first-person shooters, from role-playing video games to online gambling. This has revolutionized the way many people interact and spend their free time on the Internet.

While online gaming has been around since the 1970s, modern modes of online gaming began with services such as GameSpy and MPlayer, to which players of games would typically subscribe. Non-subscribers were limited to certain types of gameplay or certain games.

Many use the Internet to access and download music, movies and other works for their enjoyment and relaxation. As discussed above, there are paid and unpaid sources for all of these, using centralized servers and distributed peer-to-peer technologies. Discretion is needed as some of these sources take more care over the original artists' rights and over copyright laws than others.

Many use the World Wide Web to access news, weather and sports reports, to plan and book holidays and to find out more about their random ideas and casual interests.

People use chat, messaging and e-mail to make and stay in touch with friends worldwide, sometimes in the same way as some previously had pen pals. Social networking websites like MySpace, Facebook and many others like them also put and keep people in contact for their enjoyment.

The Internet has seen a growing number of Web desktops, where users can access their files, folders, and settings via the Internet.

Cyberslacking has become a serious drain on corporate resources; the average UK employee spends 57 minutes a day surfing the Web at work, according to a study by Peninsula Business Services.[35]

Subfields

[edit]Four aspects of digital sociology have been identified by Lupton (2012):[36]

- Professional digital practice: using digital media tools for professional purposes: to build networks, construct an e-profile, publicise and share research and instruct students.

- Sociological analyses of digital use: researching the ways in which people's use of digital media configures their sense of selves, their embodiment and their social relations.

- Digital data analysis: using digital data for social research, either quantitative or qualitative.

- Critical digital sociology: undertaking reflexive and critical analysis of digital media informed by social and cultural theory.

Professional digital practice

[edit]Although they have been reluctant to use social and other digital media for professional academics purposes, sociologists are slowly beginning to adopt them for teaching and research.[37] An increasing number of sociological blogs are beginning to appear and more sociologists are joining Twitter, for example. Some are writing about the best ways for sociologists to employ social media as part of academic practice and the importance of self-archiving and making sociological research open access, as well as writing for Wikipedia.

Sociological analyses of digital media use

[edit]Digital sociologists have begun to write about the use of wearable technologies as part of quantifying the body[38] and the social dimensions of big data and the algorithms that are used to interpret these data.[39] Others have directed attention at the role of digital technologies as part of the surveillance of people's activities, via such technologies as CCTV cameras and customer loyalty schemes[40] as well as the mass surveillance of the Internet that is being conducted by secret services such as the NSA.

The 'digital divide', or the differences in access to digital technologies experienced by certain social groups such as the socioeconomically disadvantaged, those of lower education levels, women and the elderly, has preoccupied many researchers in the social scientific study of digital media. However several sociologists have pointed out that while it is important to acknowledge and identify the structural inequalities inherent in differentials in digital technology use, this concept is rather simplistic and fails to incorporate the complexities of access to and knowledge about digital technologies.[41]

There is a growing interest in the ways in which social media contributes to the development of intimate relationships and concepts of the self. One of the best-known sociologists who has written about social relationships, selfhood and digital technologies is Sherry Turkle.[42][43] In her most recent book, Turkle addresses the topic of social media.[44] She argues that relationships conducted via these platforms are not as authentic as those encounters that take place "in real life".

Visual media allows the viewer to be a more passive consumer of information.[45] Viewers are more likely to develop online personas that differ from their personas in the real world. This contrast between the digital world (or 'cyberspace') and the 'real world', however, has been critiqued as 'digital dualism', a concept similar to the 'aura of the digital'.[46] Other sociologists have argued that relationships conducted through digital media are inextricably part of the 'real world'.[47] Augmented reality is an interactive experience where reality is being altered in some way by the use of digital media but not replaced.

The use of social media for social activism have also provided a focus for digital sociology. For example, numerous sociological articles,[48][49] and at least one book[50] have appeared on the use of such social media platforms as Twitter, YouTube and Facebook as a means of conveying messages about activist causes and organizing political movements.

Research has also been done on how racial minorities and the use of technology by racial minorities and other groups. These "digital practice" studies explore the ways in which the practices that groups adopt when using new technologies mitigate or reproduce social inequalities.[51][52]

Digital data analysis

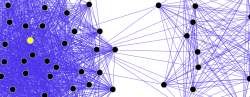

[edit]Digital sociologists use varied approaches to investigating people's use of digital media, both qualitative and quantitative. These include ethnographic research, interviews and surveys with users of technologies, and also the analysis of the data produced from people's interactions with technologies: for example, their posts on social media platforms such as Facebook, Reddit, 4chan, Tumblr and Twitter or their consuming habits on online shopping platforms. Such techniques as data scraping, social network analysis, time series analysis and textual analysis are employed to analyze both the data produced as a byproduct of users' interactions with digital media and those that they create themselves. For Contents Analysis, in 2008, Yukihiko Yoshida did a study called[53] "Leni Riefenstahl and German expressionism: research in Visual Cultural Studies using the trans-disciplinary semantic spaces of specialized dictionaries." The study took databases of images tagged with connotative and denotative keywords (a search engine) and found Riefenstahl's imagery had the same qualities as imagery tagged "degenerate" in the title of the exhibition, "Degenerate Art" in Germany at 1937.

The emergence of social media has provided sociologists with a new way of studying social phenomenon. Social media networks, such as Facebook and Twitter, are increasingly being mined for research. For example, Twitter data is easily available to researchers through the Twitter API. Twitter provides researchers with demographic data, time and location data, and connections between users. From these data, researchers gain insight into user moods and how they communicate with one another. Furthermore, social networks can be graphed and visualized.[54]

Using large data sets, like those obtained from Twitter, can be challenging. First of all, researchers have to figure out how to store this data effectively in a database. Several tools commonly used in Big Data analytics are at their disposal.[54] Since large data sets can be unwieldy and contain numerous types of data (i.e. photos, videos, GIF images), researchers have the option of storing their data in non-relational databases, such as MongoDB and Hadoop.[54] Processing and querying this data is an additional challenge. However, there are several options available to researchers. One common option is to use a querying language, such as Hive, in conjunction with Hadoop to analyze large data sets.[54]

The Internet and social media have allowed sociologists to study how controversial topics are discussed over time—otherwise known as Issue Mapping.[55] Sociologists can search social networking sites (i.e. Facebook or Twitter) for posts related to a hotly-debated topic, then parse through and analyze the text.[55] Sociologists can then use a number of easily accessible tools to visualize this data, such as MentionMapp or Twitter Streamgraph. MentionMapp shows how popular a hashtag is and Twitter Streamgraph depicts how often certain words are paired together and how their relationship changes over time.[55]

Digital surveillance

[edit]Digital surveillance occurs when digital devices record people's daily activities, collecting and storing personal data, and invading privacy.[6] With the advancement of new technologies, the act of monitoring and watching people online has increased between the years of 2010 to 2020. The invasion of privacy and recording people without consent leads to people doubting the usage of technologies which are supposed to secure and protect personal information. The storage of data and intrusiveness in digital surveillance affects human behavior. The psychological implications of digital surveillance can cause people to have concern, worry, or fear about feeling monitored all the time. Digital data is stored within security technologies, apps, social media platforms, and other technological devices that can be used in various ways for various reasons. Data collected from people using the internet can be subject to being monitored and viewed by private and public companies, friends, and other known or unknown entities.

Critical digital sociology

[edit]This aspect of digital sociology is perhaps what makes it distinctive from other approaches to studying the digital world. In adopting a critical reflexive approach, sociologists are able to address the implications of the digital for sociological practice itself. It has been argued that digital sociology offers a way of addressing the changing relations between social relations and the analysis of these relations, putting into question what social research is, and indeed, what sociology is now as social relations and society have become in many respects mediated via digital technologies.[56]

How should sociology respond to the emergent forms of both 'small data' and 'big data' that are collected in vast amounts as part of people's interactions with digital technologies and the development of data industries using these data to conduct their own social research? Does this suggest that a "coming crisis in empirical sociology" might be on the horizon?[57] How are the identities and work practices of sociologists themselves becoming implicated within and disciplined by digital technologies such as citation metrics?[58]

These questions are central to critical digital sociology, which reflects upon the role of sociology itself in the analysis of digital technologies as well as the impact of digital technologies upon sociology.[59]

To these four aspects add the following subfields of digital sociology:

Public digital sociology

[edit]Public sociology using digital media is a form of public sociology that involves publishing sociological materials in online accessible spaces and subsequent interaction with publics in these spaces. This has been referred to as "e-public sociology".[60]

Social media has changed the ways the public sociology was perceived and given rise to digital evolution in this field. The vast open platform of communication has provided opportunities for sociologists to come out from the notion of small group sociology or publics to a vast audience.

Blogging was the initial social media platform being utilized by sociologists. Sociologists like Eszter Hargittai, Chris Bertram, and Kieran Healy were few amongst those who started using blogging for sociology. New discussion groups about sociology and related philosophy were the consequences of social media impact. The vast number of comments and discussions thus became a part of understanding sociology. One of such famous groups was Crooked Timber. Getting feedback on such social sites is faster and impactful. Disintermediation, visibility, and measurement are the major effects of e-public sociology. Other social media tools like Twitter and Facebook also became the tools for a sociologist. "Public Sociology in the Age of Social Media".[61]

Digital transformation of sociological theory

[edit]Information and communication technology as well as the proliferation of digital data are revolutionizing sociological research. Whereas there is already much methodological innovation in digital humanities and computational social sciences, theory development in the social sciences and humanities still consists mainly of print theories of computer cultures or societies. These analogue theories of the digital transformation, however, fail to account for how profoundly the digital transformation of the social sciences and humanities is changing the epistemic core of these fields. Digital methods constitute more than providers of ever-bigger digital datasets for testing of analogue theories, but also require new forms of digital theorising.[62] The ambition of research programmes on the digital transformation of social theory is therefore to translate analogue into digital social theories so as to complement traditional analogue social theories of the digital transformation by digital theories of digital societies.[63]

See also

[edit]- Anthropology of cyberspace

- Computational social science

- Cyber-dissident

- Digital anthropology

- Digital humanities

- Digital Revolution

- Internet culture

- Internet vigilantism

- Slacktivism

- Social informatics

- Social web

- Sociology of science and technology

- Software studies

- Technology and society

- Tribe (internet)

- Virtual volunteering

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Robert Darnton, The Library in the New Age Archived 2008-05-26 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Review of Books, Volume 55, Number 10. June 12, 2008. Retrieved on 22 December 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Paul DiMaggio, Eszter Hargittai, W. Russell Neuman, and John P. Robinson, Social Implications of the Internet, Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 27: 307-336 (Volume publication date August 2001), doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.307 [1] Archived 2020-05-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wynn, J. (2009) Digital sociology: emergent technologies in the field and the classroom. Sociological Forum, 24(2), 448--456

- ^ Neal, R. (2010) Expanding Sentience: Introducing Digital Sociology for moving beyond Buzz Metrics in a World of Growing Online Socialization. Lulu

- ^ Orton-Johnson, K. and Prior, N. (eds) (2013) Digital Sociology: Critical Perspectives. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan

- ^ a b Lupton, D. (2015) Digital Sociology. London: Routledge

- ^ Daniels, J.; Gregory, K.; Cottom, T.M. (2015-02-27). "The First Digital Sociology Conference 2015". Archived from the original on 2021-10-26 – via Digital Sociology MiniConference, organized in conjunction with the Eastern Sociological Society meetings.

- ^ Lauren F. Sessions, "How offline gatherings affect online community members: when virtual community members ‘meetup’.""Information, Communication, and Society"13,3(April, 2010):375-395

- ^ Bo Xie, B. ‘The mutual shaping of online and offline social relationships."Information Research, 1,3(2008):n.p.

- ^ Lee Rainie, John Horrigan, Barry Wellman, and Jeffrey Boase. (2006)"The Strength of Internet Ties" Pew Internet and American Life Project. Washington, D.C.

- ^ Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook "friends:" Social capital and college students' use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4).

- ^ "Social Isolation and New Technology". 4 November 2009. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ Richard Jensen. "Military History on the Electronic Frontier: Wikipedia Fights the War of 1812," The Journal of Military History (October 2012) 76#4 pp 1165-82 online Archived 2017-12-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Charles, Megan (7 March 2014). "Meeting Facebook Friends Face To Face Causes Anxiety (Study)". Business 2 Community. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ Atzori, Luigi; Iera, Antonio; Morabito, Giacomo; Nitti, Michele (2012). "The Social Internet of Things (SIoT) – When social networks meet the Internet of Things: Concept, architecture and network characterization". Computer Networks. 56 (16): 3594–3608. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2012.07.010. ISSN 1389-1286.

- ^ a b Mattern, Friedemann; Floerkemeier, Christian (2010). "From the Internet of Computers to the Internet of Things". From Active Data Management to Event-Based Systems and More. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 6462. pp. 242–259. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.171.145. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-17226-7_15. ISBN 978-3-642-17225-0. ISSN 0302-9743.

- ^ Simonite, Tom. "Silicon Valley to Get a Cellular Network, Just for Things". Technology Review. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ^ Kranz, Matthias, Luis Roalter, and Florian Michahelles. "Things that twitter: social networks and the internet of things." What can the Internet of Things do for the Citizen (CIoT) Workshop at The Eighth International Conference on Pervasive Computing (Pervasive 2010). 2010.

- ^ Weber, Rolf H. (2010). "Internet of Things – New security and privacy challenges". Computer Law & Security Review. 26 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1016/j.clsr.2009.11.008. ISSN 0267-3649. S2CID 6968691.

- ^ a b Fussey and Roth, Pete and Silke (June 1, 2020). "Digitizing Sociology: Continuity and Change in the Internet Era". Department of Sociology. 54 (4): 659–674. doi:10.1177/0038038520918562. S2CID 220533863.

- ^ a b Rosen, L. D; Lim, A. F; Felt, J; Carrier, L. M; Cheever, N. A; Lara-Ruiz, J. M; Mendoza, J. S; Rokkum, J (2014). "Media and technology use predicts ill-being among children, preteens and teenagers independent of the negative health impacts of exercise and eating habits". Computers in Human Behavior. 35: 364–375. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.036. PMC 4338000. PMID 25717216.

- ^ a b "Children, Adolescents, and the Media" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-10-24.

- ^ Unknown, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.688.1918[permanent dead link]

- ^ Druin, Allison (1999-10-02). "The Role of Children in the Design Technology". Archived from the original on 2018-04-25. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- ^ "Families' experiences of caring for technology-dependent children: a temporal perspective" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-14.

- ^ "A Tablet Computer for Young Children? Exploring Its Viability for Early Childhood Education" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-31.

- ^ "Document Resume - Perspectives on Technology and Education Research: Lessons from the Past and Present" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-19.

- ^ ""Communication, Conflict, and the Quality of Family Relationships" by Alan Sillars, Daniel J. Canary and Melissa Tafoya in Handbook of Family Communication, edited by Anita L. Vangelisti. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Aassociates, Publishers, 2004" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-24. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- ^ "How the Internet Reinforces Inequality in the Real World" Archived 2013-02-11 at the Wayback Machine The Atlantic February 6, 2013

- ^ "E-commerce will make the shopping mall a retail wasteland" ZDNet, January 17, 2013

- ^ Kiva Is Not Quite What It Seems Archived 2010-02-10 at the Wayback Machine, by David Roodman, Center for Global Development, Oct. 2, 2009, as accessed Jan. 2 & 16, 2010

- ^ Confusion on Where Money Lent via Kiva Goes Archived 2018-01-21 at the Wayback Machine, by Stephanie Strom, in The New York Times, Nov. 8, 2009, as accessed Jan. 2 & 16, 2010

- ^ "Zidisha Set to "Expand" in Peer-to-Peer Microfinance", Microfinance Focus, Feb 2010 Archived 2011-10-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chivers, Tom (Dec 21, 2010). "Internet pornography block plans: other attempts to control the internet". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "Scotsman.com News - Net abuse hits small city firms". Archived from the original on 2006-10-20. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ^ Lupton, D. (2012) "Digital sociology: an introduction" Archived 2021-10-26 at the Wayback Machine. Sydney: University of Sydney

- ^ Carrigan, M. (2013) "The emergence of sociological media? Is social media becoming mainstream within UK sociology?" Archived 2021-10-23 at the Wayback Machine. Mark Carrigan.net

- ^ Lupton, D. (2013) "Quantifying the body: monitoring and measuring health in the age of mHealth technologies" Archived 2020-04-21 at the Wayback Machine. Critical Public Health

- ^ Cheney-Lippold, J. (2011) "A new algorithmic identity: soft biopolitics and the modulation of control" Archived 2015-05-18 at the Wayback Machine. Theory, Culture & Society, 28(6), 164-81.

- ^ Graham, S. and Wood, D. (2003) "Digitizing surveillance: categorization, space, inequality" Archived 2016-11-11 at the Wayback Machine. Critical Social Policy, 23(2),227-48.

- ^ Willis, S. and Tranter, B. (2006) "Beyond the 'digital divide': Internet diffusion and inequality in Australia" Archived 2015-05-18 at the Wayback Machine. Journal of Sociology, 42(1), 43-59

- ^ Turkle, S. (1984) "The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit" Archived 2021-09-25 at the Wayback Machine. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- ^ Turkle, S. (1995) "Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet". New York: Simon & Schuster.

- ^ Turkle, S. (2011) Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic Books

- ^ Wynn, Jonathan R. "Digital Sociology: Emergent Technologies in the Field and the Classroom". Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2021-10-23.

- ^ Betancourt, M. (2006) "The Aura of the Digital" Archived 2020-05-26 at the Wayback Machine, CTheory

- ^ Jurgenson, N. (2012) "When atoms meet bits: social media, the mobile web and augmented revolution" Archived 2023-01-17 at the Wayback Machine. Future Internet, 4, 83-91

- ^ Maireder, A. and Schwartzenegger, C. (2011) A movement of connected individuals: social media in the Austrian student protests 2009. Information, Communication & Society, 15(2), 1-25.

- ^ Lim, M. (2012) "Clicks, cabs, and coffee houses: social media and oppositional movements in Egypt" Archived 2015-05-01 at the Wayback Machine, 2004-2011. Journal of Communication, 62(2), 231-248.

- ^ Murthy, D. (2013) Twitter: Social Communication in the Twitter Age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- ^ Graham, R. (2014) The Digital Practices of African Americans: An Approach to Studying Cultural Change in the Information Society. New York: Peter Lang.

- ^ Graham, R. (2016) "The Content of Our #Characters: Black Twitter as Counterpublic". Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 2(4) 433 – 449

- ^ Yoshida, Yukihiko, Leni Riefenstahl and German Expressionism: A Study of Visual Cultural Studies Using Transdisciplinary Semantic Space of Specialized Dictionaries, Technoetic Arts: a journal of speculative research (Editor Roy Ascott), Volume 8, Issue3, intellect, 2008

- ^ a b c d Murthy, Dhiraj; Bowman, Sawyer A (2014-11-25). "Big Data solutions on a small scale: Evaluating accessible high-performance computing for social research". Big Data & Society. 1 (2): 205395171455910. doi:10.1177/2053951714559105.

- ^ a b c Marres, Noortje; Gerlitz, Carolin (2015-08-14). "Interface Methods: Renegotiating Relations between Digital Social Research, STS and Sociology" (PDF). The Sociological Review. 64 (1): 21–46. doi:10.1111/1467-954x.12314. S2CID 145741146. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-22. Retrieved 2021-10-23.

- ^ Marres. N. (2013) "What is digital sociology?" Archived 2021-10-26 at the Wayback Machine CSISP Online

- ^ Savage, M. and Burrows, R. (2007) "The coming crisis of empirical sociology" Archived 2013-03-13 at the Wayback Machine. Sociology, 41(5),885-889

- ^ Burrows, R. (2012) Living with the h-index? Metric assemblages in the contemporary academy. The Sociological Review, 60(2), 355—72.

- ^ Lupton, D. (2012) "Digital sociology part 3: digital research" Archived 2021-10-26 at the Wayback Machine. This Sociological Life

- ^ Christopher J. Schneider (2014). Social Media and e-Public Sociology. In Ariane Hanemaayer and Christopher J. Schneider, editors, The Public Sociology Debate: Ethics and Engagement, University of British Columbia Press: 205-224

- ^ Healy, Kieran. "Public Sociology in the Age of Social Media." Berkeley Sociology Journal (2015): 1-16. APA

- ^ Kitchin, R. "Big Data, new epistemologies and paradigm shifts." Big Data & Society, 1(1) (2014): doi:10.1177/2053951714528481. APA

- ^ Roth S., Dahms H., Welz F., and Cattacin S. (2019) "Digital transformation of social theory" Archived 2021-10-23 at the Wayback Machine. Special Issue of Technological Forecasting and Social Change.

Further reading

[edit]- John A. Bargh and Katelyn Y. A. McKenna, The Internet and Social Life, Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 55: 573-560 (Volume publication date February 2004), doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141922 [2]

- Allison Cavanagh, Sociology in the Age of the Internet, McGraw-Hill International, 2007, ISBN 9780335217267

- Dolata, Ulrich; Schrape, Jan-Felix (2023). "Platform companies on the internet as a new organizational form. A sociological perspective". Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research. 36: 1–20. doi:10.1080/13511610.2023.2182217. S2CID 257575411.

- Christine Hine, Virtual Methods: Issues in Social Research on the Internet, Berg Publishers, 2005, ISBN 9781845200855

- Rob Kling, The Internet for Sociologists, Contemporary Sociology, Vol. 26, No. 4 (Jul., 1997), pp. 434–758

- Joan Ferrante-Wallace, Joan Ferrante, Sociology.net: Sociology on the Internet, Thomson Wadsworth, 1996, ISBN 9780534527563

- Daniel A. Menchik and Xiaoli Tian. (2008) "Putting Social Context into Text: The Semiotics of Email Interaction." The American Journal of Sociology. 114:2 pp. 332–70.

- Carla G. Surratt, "The Internet and Social Change", McFarland, 2001, ISBN 978-0786410194

- D. R. Wilson, Researching Sociology on the Internet, Thomson/Wadsworth, 2004, ISBN 9780534568955

- Cottom, T.M. Why is Digital Sociology. https://tressiemc.com/uncategorized/why-is-digital-sociology

External links

[edit]- What is Internet Sociology and Why Does it Matter?

- Internet Sociology in Germany Website of Germany's first Internet Sociologist Stephan G. Humer, established in 1999

- Sociology and the Internet (A short introduction, originally put-together for delegates to the ATSS 2001 Conference.)

- Peculiarities of Cyberspace — Building Blocks for an Internet Sociology (Articles the social structure and dynamic of internetcommunities. Presented by dr Albert Benschop, University of Amsterdam.)

- Communication and Information Technologies Section of the American Sociological Association

- The Impact of the Internet on Sociology: The Importance of the Communication and Information Technologies Section of the American Sociological Association

- Sociology and the Internet (course)

- Sociology of the Internet (link collection)

- Internet sociologist

- The Sociology of the Internet

- Digital Sociology

- Culture Digitally blog

- Cyborgology blog

- Digital Sociology storify