Sister republic

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2018) |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

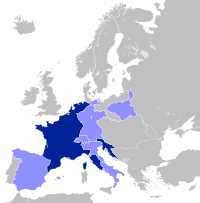

Sister republics (French: république sœur, pronounced [ʁepyblik sœʁ] ⓘ) were republics established by the French First Republic or local pro-French revolutionaries during the French Revolutionary Wars. Though nominally independent, sister republics were heavily reliant on French protection, making them in effect client states of France. This became particularly evident after the First French Empire was established in 1804, after which France annexed several sister republics and transformed the remainder into monarchies ruled by members of the House of Bonaparte.

History

[edit]The French Revolution was a period of social and political upheaval in France from 1789 until 1799. The Republicans who overthrew the monarchy were driven by ideas of popular sovereignty, rule of law, and representative democracy. The Republicans borrowed ideas and values from Whiggism and Enlightenment philosophers. The French Republic supported the spread of republican principles in Europe. According to Paul D. Van Wie most of these sister republics became a means of controlling occupied lands as client regimes through a mix of French and local power.[1]

Sister republics in Italy

[edit]- The Subalpine Republic (1800–1802), annexed by the French Republic

- The Piedmontese Republic (1798–1799), conquered by Austro-Russian troops and rendered back to Sardinia, but reconquered by Napoleon in 1800 and renamed the Subalpine Republic (Novara to the Italian Republic)

- The

Republic of Alba (1796), reconquered by the Kingdom of Sardinia

Republic of Alba (1796), reconquered by the Kingdom of Sardinia

- The

- The Piedmontese Republic (1798–1799), conquered by Austro-Russian troops and rendered back to Sardinia, but reconquered by Napoleon in 1800 and renamed the Subalpine Republic (Novara to the Italian Republic)

- The

Parthenopean Republic (1799), reconquered by the Sanfedisti for the King of Naples and Sicily

Parthenopean Republic (1799), reconquered by the Sanfedisti for the King of Naples and Sicily

- The

Republic of Pescara (1799), reunited with the Kingdom of Naples

Republic of Pescara (1799), reunited with the Kingdom of Naples

- The

- The

Roman Republic (1798–1799), ended with the restoration of the Papal States

Roman Republic (1798–1799), ended with the restoration of the Papal States

- The

Anconine Republic (1797–1798), joined the Roman Republic

Anconine Republic (1797–1798), joined the Roman Republic - The

Tiberina Republic (1798–1799), joined the Roman Republic

Tiberina Republic (1798–1799), joined the Roman Republic

- The

- The

Ligurian Republic (1797–1805), annexed by the French Empire

Ligurian Republic (1797–1805), annexed by the French Empire - The

Republic of Lucca (1799 and 1800–01), later continued (1801–05) under the old oligarchy and replaced by the Principality of Lucca and Piombino

Republic of Lucca (1799 and 1800–01), later continued (1801–05) under the old oligarchy and replaced by the Principality of Lucca and Piombino - The

Italian Republic (1802–1805), transformed into the Kingdom of Italy

Italian Republic (1802–1805), transformed into the Kingdom of Italy

- The

Cisalpine Republic (1797–1802), transformed into the Italian Republic

Cisalpine Republic (1797–1802), transformed into the Italian Republic

- The

Cispadane Republic (1796–1797), formed the Cisalpine Republic

Cispadane Republic (1796–1797), formed the Cisalpine Republic

- The Bolognese Republic (1796), annexed by the Cispadane Republic

- The

Transpadane Republic (1796–1797), formed the Cisalpine Republic

Transpadane Republic (1796–1797), formed the Cisalpine Republic - The

Republic of Crema (1797), formed the Cisalpine Republic

Republic of Crema (1797), formed the Cisalpine Republic - The Republic of Bergamo (1797), formed the Cisalpine Republic

- The Republic of Brescia (1797), annexed by the Cisalpine Republic

- The

- The

- The Provisional Municipality of Venice (1797–1798), annexed by the Austrian Empire

Other sister republics

[edit]

- The

Republic of Bouillon (1794–1795)

Republic of Bouillon (1794–1795) - The

Republic of Liège (1789–1791)

Republic of Liège (1789–1791) - The Rauracian Republic (1792–1793), French revolutionary republic in Basel

- The Lémanique Republic (1798), joined the Helvetic Republic

- The Republic of Mainz (1793), French revolutionary republic in Rhenish Hesse and the Electoral Palatinate

- The

Batavian Republic (1795–1806)

Batavian Republic (1795–1806) - The

Cisrhenian Republic (1797)

Cisrhenian Republic (1797) - The

Irish Republic (1798), accompanied General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert's Irish expedition in support of the Irish Rebellion of 1798

Irish Republic (1798), accompanied General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert's Irish expedition in support of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 - The

Helvetic Republic (1798–1803)

Helvetic Republic (1798–1803) - The

Republic of Danzig (1807–1814)

Republic of Danzig (1807–1814) - The

Rhodanic Republic (1802–1810) (Valais)

Rhodanic Republic (1802–1810) (Valais)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Van Wie, Paul D. (1999). Image, History, and Politics: The Coinage of Modern Europe. University Press of America. pp. 116–7. ISBN 9780761812227. Retrieved 24 June 2015.