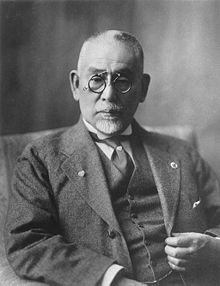

Gotō Shinpei

Gotō Shinpei | |

|---|---|

後藤 新平 | |

| |

| Born | 24 July 1857 |

| Died | 13 April 1929 (aged 71) |

| Resting place | Aoyama Cemetery, Tokyo, Japan |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Occupation(s) | Politician, physician |

Count Gotō Shinpei (後藤 新平, 24 July 1857 – 13 April 1929) was a Japanese politician, physician and cabinet minister of the Taishō and early Shōwa period Empire of Japan. He served as the head of civilian affairs of Japanese Taiwan, the first director of the South Manchuria Railway, the seventh mayor of Tokyo City, the first Chief Scout of Japan, the first Director-General of NHK, the third principal of Takushoku University, and in a number of cabinet posts. Gotō was one of the most important politicians and administrators in Japanese national government during a time of modernization and reform in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[1] He was also a significant advocate for Japanese colonialism, and defended Japan's violent incursions in China and Korea.

Early life

[edit]Gotō was born in Isawa, Mutsu Province (present-day in Iwate Prefecture) to Gotō Sanetaka, a retainer of the Rusu clan, itself vassal to the warlord Date Masamune of the Sendai domain. Though distinguished with samurai status, the Gotō family was not an affluent one, and ranked somewhere between fifth and twentieth in the Rusu clan hierarchy.[2] In 1868, the Sendai domain joined the alliance of domains in north-eastern Japan (present-day Tohoku) opposed to the Meiji Restoration and was defeated in the Boshin War. As a result, the Gotō family surrendered their samurai status and remained on their native soil as farmers.[3] With the re-organization of Isawa into a prefecture under direct control of the newly formed Meiji government in September 1869, Gotō came to the notice of government officials and was selected to run errands and aid in administration of the new territory. This gave Gotō the opportunity to visit Tokyo in 1871 under the auspices of Kaetsu Ujifusa, who had succeeded Yasuba Yasukazu as senior counselor of Isawa. The trip was largely unproductive, however, and he returned home in 1872.[4]

Though initially reluctant to pursue a career in medicine, at the encouragement of an earlier acquaintance he entered Sukagawa medical school in Fukushima Prefecture aged seventeen, and became a physician at the Aichi Prefectural Hospital in Nagoya after graduation.[5] In 1877, he served as a government medic during the Satsuma Rebellion. At the age of 25, he became president of the Nagoya Medical School.[6]

Having distinguished himself through his work at the Nagoya Medical School and at the military hospital in Osaka during the Satsuma Rebellion, Gotō joined the Home Ministry's medical bureau (衛生局) in 1883, eventually becoming its head. In 1890 Gotō was sent by the Japanese government to Germany for further studies.[6] While at the ministry, in 1890 he published his Principles of National Health (国家衛生原理) and took part in the creation of new sewage and water facilities in Tokyo. This recommended him to Army Vice-Minister Kodama Gentarō (1852–1906), who made Gotō chief of the Army Quarantine Office looking after the return of more than 230,000 soldiers from the First Sino-Japanese War (1895–95). After the war, Gotō returned to the Home Ministry, but remained involved in overseas affairs, advising the new Japanese administration on Taiwan about health issues. In 1896, Kodama, now governor-general of Taiwan, asked Gotō to join him there, eventually making him the first civilian governor of the island in 1898.[7]

Taiwan

[edit]At the end of the war, Qing China ceded Formosa and the Pescadores (see modern-day Taiwan) to Japan via the Treaty of Shimonoseki. Kodama became the Governor-General of Taiwan, and Gotō was asked to become the head of civilian affairs in his government.[8][9]

Gotō ordered a land survey and recruited Scottish engineer William Kinninmond Burton to develop an infrastructure for drinking water and sewage disposal. Gotō replaced the military police by a civilian police force, forbade government officials and teachers from wearing uniforms and swords, and revived traditional forms of social control by enlisting village elders and headmen into the administration.[10] Gotō also built a public hospital and medical college in Taipei, and clinics to treat tropical diseases around the island. Opium addiction was an endemic problem in China at the time, and Taiwan was no exception. Gotō recommended a policy of the gradual prohibition of opium. Under this scheme, opium could only be purchased from licensed retailers. As a result of the strict enforcement, the number of addicts dropped from 165,000 in 1900 to fewer than 8,000 by 1941,[11] none of whom was younger than 30. In addition, as government revenues from opium sales was lucrative and Gotō used opium sales licenses to reward Taiwanese elite loyal to the Japanese Empire and those who assisted in the suppression of the Taiwan Yiminjun (Chinese: 台灣義民軍), an armed group that resisted Japanese rule. The plan achieved both its purposes: opium addiction dropped gradually and the activities of the Yiminjun were undermined.

As a doctor by training, Gotō believed that Taiwan must be ruled by "biological principles" (生物学の原則), i.e. that he must first understand the habits of the Taiwanese population, as well as the reasons for their existence, before creating corresponding policies. For this purpose, he created and headed the Provisional Council for the Investigation of Old Habits of Taiwan.

Gotō also established the economic framework for the colony by government monopolization of sugar, salt, tobacco and camphor and also for the development of ports and railways. He recruited Nitobe Inazō to develop long-range plans for forestry and sub-tropical agriculture. By the time Gotō left office, he had tripled the road system, established a post office network, telephone and telegraph services, a hydroelectric power plant, newspapers, and the Bank of Taiwan. The colony was economically self-supporting and by 1905 no longer required the support of the home government despite the numerous large-scale infrastructure projects being undertaken.[12]

In the early days of Japanese colonial rule police were deployed to the cities to maintain order, often through brutal means, while the military was deployed to the countryside as a counterinsurgency and policing force. The brutality of early Japanese policing backfired and often inspired rebellion and insurrection instead of quashing it. This system was reformed by Goto Shinpei who sought to co-opt existing traditions to expand Japanese power. Out of the Qing baojia system he crafted the Hoko system of community control. The Hoko system eventually became the primary method by which the Japanese authorities went about all sorts of tasks from tax collecting, to opium smoking abatement, to keeping tabs on the population. Under the Hoko system every community was broken down into Ko, groups of ten neighboring households. When a person was convicted of a serious crime, the person's entire Ko would be fined. The system only became more effective as it was integrated with the local police.[13]

Under Gotō police stations were established in every part of the island. Rural police stations took on extra duties with those in the aboriginal regions operating schools known as “savage children’s educational institutes” to assimilate aboriginal children into Japanese culture. The local police station also controlled the rifles which aboriginal men relied upon for hunting as well as operated small barter stations which created small captive economies.[13]

Politician

[edit]In 1906, Gotō became the first director of the South Manchuria Railway Company. In 1908, he returned to Japan as Minister of Communications and the head of the Railway Bureau (Tetsudōin), under the second Katsura administration. In 1912, Gotō became director of the Colonization Bureau (拓殖局総裁, Takushokukyoku). A close confidant of Prime Minister Katsura, he assisted in the formation of the Rikken Dōshikai political party after the Taishō political crisis in 1912. Following Katsura's death, he allied with Yamagata Aritomo and became Home Minister in 1916, and Foreign Minister in the Terauchi administration in 1918.[14]

A strong believer in Pan-Asianism, Gotō pushed for an aggressive and expansionist Japanese foreign policy during World War I, and strongly endorsed the Japanese intervention in Siberia.[14]

In April 1919, after the March First Movement protests in Korea, Gotō gave a speech in which he defended the violent suppression of the protests and Japan's colonization of Korea. He argued that Korea was uncivilized and that Japan was on a noble civilizing mission.[15]

Gotō served as Mayor of Tokyo City in 1920, and again as Home Minister in 1923, contributing to the reconstruction of Tokyo following the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake.[14]

In 1924, Citizen Watch's forerunner, the Shokosha Watch Research Watch Institute, produced its first pocket watch, and presented it to mayor Gotō. Gotō named the watch "Citizen" with the hope that the watch, then a luxury item, would one day become widely available to ordinary citizens.[citation needed]

In December 1924, Tokyo police reported that Goto had gone mad at the age of 68.[16]

Gotō died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1929 while on a visit to Okayama.[17] His papers are preserved at the Gotō Shinpei Memorial Museum, which is situated in his birthplace, Mizusawa City, in Iwate Prefecture.

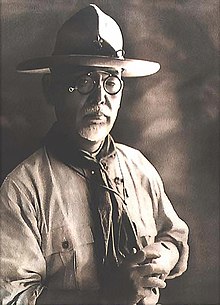

Scouting

[edit]

Gotō was made the first Chief Scout of Japan and tasked with reforming the newly federated organization in the early 1920s. As Minister of Railways, Count Gotō traveled around the country, and was able to promote Scouting all over Japan in his spare time. In 1956 he posthumously received the highest distinction of the Scout Association of Japan, the Golden Pheasant Award.[18]

Honors

[edit]From the corresponding Japanese Wikipedia article

Peerages

[edit]- Baron (11 April 1906)

- Viscount (25 September 1922)

- Count (10 November 1928)

Decorations

[edit]- Order of the Sacred Treasure, 3rd Class (27 June 1901)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers (7 September 1920; Grand Cordon: 13 November 1906; Second Class: 4 December 1902; Sixth Class: 30 November 1895)

Political offices

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 310.

- ^ Kitaoka (2021), p. 21-22.

- ^ Kitaoka (2021), p. 23.

- ^ Kitaoka (2021), p. 24-25.

- ^ Kitaoka (2021), p. 25-26.

- ^ a b Frédéric (2002), p. 264.

- ^ Sewell, Bill (2004). "Reconsidering the Modern in Japanese History: Modernity in the Service of the Prewar Japanese Empire". Japan Railway & Transport Review. 16. Japan Review: 213–258.

- ^ Tsai (2005), pp. 12–14.

- ^ Kublin, Hyman (1959). "The Evolution of Japanese Colonialism". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 2 (1): 67–84. ISSN 0010-4175.

- ^ Tsai (2005), pp. 12–4.

- ^ Jennings (1997), pp. 21–25.

- ^ Rubinstein (2007), pp. 209–211.

- ^ a b Crook, Steven. "Highways and Byways: Handcuffed to the past". www.taipeitimes.com. Taipei Times. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Tucker (2002), pp. 798–799.

- ^ Palmer, Brandon (December 2020). "The March First Movement in America: The Campaign to Win American Support". Korea Journal. 60 (4): 209. ISSN 0023-3900 – via DBpia.

- ^ The Daily Worker (13 December 1924). "Capitalist Solon Crazy". Chronicling America. The Daily Worker. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ Perez (2002), p. 99.

- ^ 䝪䞊䜲䝇䜹䜴䝖日本連盟 きじ章受章者 [Recipient of the Golden Pheasant Award of the Scout Association of Japan] (PDF). Reinanzaka Scout Club (in Japanese). 23 May 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Jennings, John (1997). The Opium Empire: Japanese Imperialism and Drug Trafficking in Asia, 1895-1945. Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 0275957594.

- Frédéric, Louis (2002). Japan Encyclopedia. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674017536.

- Kitaoka, Shinichi (2021). Gotō Shinpei, Statesman of Vision: Research, Public Health, and Development (First English ed.). Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture. ISBN 9784866581835.

- Perez, Louis G (2002). Japan at War: An Encyclopedia. ABC CLIO. ISBN 1851098798.

- Rubinstein, Murray A (2007). Taiwan: A New History. M E Sharpe. ISBN 978-0765614940.

- Tsai, Henry (2005). Lee Teng-Hui and Taiwan's Quest for Identity. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1403977178.

- Tucker, Spencer (2002). World War I: A Student Encyclopedia. ABC CLIO. ISBN 1851098798.

External links

[edit] Media related to Gotō Shinpei at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gotō Shinpei at Wikimedia Commons- Goto Shimpei no Kai

- Goto, Shinpei | Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures (National Diet Library)

- Newspaper clippings about Gotō Shinpei in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Film Address "Ethicization of Politics" by Shinpei Goto, 1926 (National Film Archive of Japan)

- 1857 births

- 1929 deaths

- Japanese healthcare managers

- Government ministers of Japan

- Ministers for foreign affairs of Japan

- Ministers of home affairs of Japan

- Scouting in Japan

- Kazoku

- Taiwan under Japanese rule

- Mayors of Tokyo

- Scouting pioneers

- Politicians from Iwate Prefecture

- People of Meiji-period Japan

- Rikken Dōshikai politicians

- 20th-century Japanese politicians

- 20th-century mayors of places in Japan

- Japanese people in rail transport

- Citizen Watch

- Pan-Asianists

- Japanese military doctors