Shanxi

Shanxi

山西 | |

|---|---|

| Province of Shanxi | |

| Name transcription(s) | |

| • Chinese | 山西省 (Shānxī shěng) |

| • Abbreviation | SX / 晋 (Jìn) |

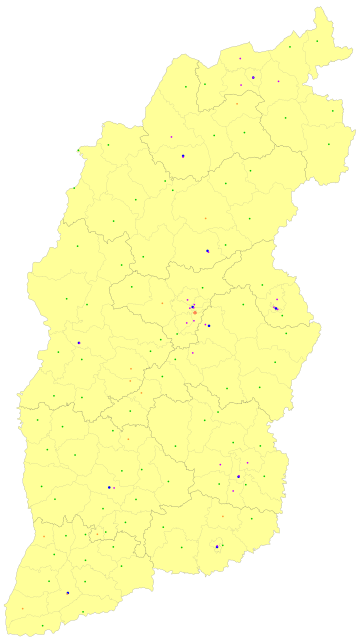

Location of Shanxi in China | |

| Coordinates: 37°42′N 112°24′E / 37.7°N 112.4°E | |

| Country | China |

| Named for | "west of the Taihang Mountains" |

| Capital (and largest city) | Taiyuan |

| Divisions | 11 prefectures, 119 counties, 1388 townships |

| Government | |

| • Type | Province |

| • Body | Shanxi Provincial People's Congress |

| • CCP Secretary | Tang Dengjie |

| • Congress chairman | Tang Dengjie |

| • Governor | Jin Xiangjun |

| • CPPCC chairman | Wu Cunrong |

| • National People's Congress Representation | 67 deputies |

| Area | |

• Total | 156,000 km2 (60,000 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 19th |

| Highest elevation | 3,058 m (10,033 ft) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

• Total | 34,915,616 |

| • Rank | 18th |

| • Density | 220/km2 (580/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 19th |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic composition | |

| • Languages and dialects | |

| GDP (2023)[3] | |

| • Total | CN¥2,570 billion (20th; US$365 billion) |

| • Per capita | CN¥73,984 (15th; US$10,499) |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-SX |

| HDI (2022) | 0.791[4] (13th) – high |

| Website | www |

| Shanxi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Shanxi" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 山西 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Shansi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "West of the (Taihang) Mountains" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Shanxi[a] is a province in North China. Its capital and largest city of the province is Taiyuan, while its next most populated prefecture-level cities are Changzhi and Datong. Its one-character abbreviation is 晋 (Jìn), after the state of Jin that existed there during the Spring and Autumn period (c. 770 – c. 481 BC).

The name Shanxi means 'west of the mountains', a reference to its location west of the Taihang Mountains.[6] Shanxi borders Hebei to the east, Henan to the south, Shaanxi to the west and Inner Mongolia to the north. Shanxi's terrain is characterised by a plateau bounded partly by mountain ranges. Shanxi's culture is largely dominated by the ethnic Han majority, who make up over 99% of its population.[citation needed] Jin Chinese is considered by some linguists to be a distinct language from Mandarin and its geographical range covers most of Shanxi. Both Jin and Mandarin are spoken in Shanxi.

Shanxi is a leading producer of coal in China, possessing roughly a third of China's total coal deposits. Nevertheless, Shanxi's GDP per capita remains below the national average. The province hosts the Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center.

The province is also known for having by far the largest number of historic buildings among all Chinese provinces, by possessing over 70% of China's surviving buildings built during or predating the Song dynasty.[7] Also notable are the Yungang Grottoes in Datong, which date back over 1500 years.

History

[edit]Pre-Imperial China

[edit]In the Spring and Autumn period (c. 770 – c. 481 BC), the state of Jin was located in what is now Shanxi. It underwent a three-way split into the states of Han, Zhao, and Wei in 403 BC, a traditional date sometimes taken as the start of the Warring States period (c. 473 – 221 BC). By 221 BC, all of these states had fallen to the state of Qin, which established the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC).[8]

Imperial China

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2013) |

The Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220) ruled Shanxi as the province of Bingzhou.

During the invasion of northern nomads in the Sixteen Kingdoms period (304–439), several regimes including the Later Zhao, Former Yan, Former Qin, and Later Yan continuously controlled Shanxi. They were followed by Northern Wei (386–534), a Xianbei kingdom, which had one of its earlier capitals at present-day Datong in northern Shanxi, and which went on to rule nearly all of northern China.

The Tang dynasty (618–907) originated in Taiyuan. During the Tang dynasty and after, present day Shanxi was called Hédōng (河東), or "east of the (Yellow) river". Empress Wu Zetian, one of China's only female rulers, was born in Shanxi in 624.

During the first part of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–960), Shanxi supplied rulers of three of the Five Dynasties. Among the Ten Kingdoms, it was the only one located in northern China. Shanxi was initially home to the jiedushi (commander) of Hedong, Li Cunxu, who overthrew the first of the Five Dynasties, Later Liang (907–923) to establish the second, Later Tang (923–936). Another jiedushi of Hedong, Shi Jingtang, overthrew Later Tang to establish the third of the Five Dynasties, Later Jin, and yet another jiedushi of Hedong, Liu Zhiyuan, established the fourth of the Five Dynasties (Later Han) after the Khitans destroyed Later Jin, the third. Finally, when the fifth of the Five Dynasties (Later Zhou) emerged, the jiedushi of Hedong at the time, Liu Chong, rebelled and established an independent state called Northern Han, one of the Ten Kingdoms, in what is now northern and central Shanxi.

Shi Jingtang, founder of the Later Jin, the third of the Five Dynasties, ceded a piece of northern China to the Khitans in return for military assistance. This territory, called the Sixteen Prefectures of Yanyun, included a part of northern Shanxi. The ceded territory became a major problem for the Song dynasty's defense against the Khitans for the next 100 years because it lay south of the Great Wall.

The later Zhou, the last dynasty of the Five Dynasties period was founded by Guo Wei, a Han Chinese, who served as the Assistant Military Commissioner at the court of the Later Han which was ruled by Shatuo Turks. He founded his dynasty by launching a military coup against the Turkic Later Han Emperor however, his newly established dynasty was short-lived and was conquered by the Song dynasty in 960.

In the early years of the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127), the sixteen ceded prefectures continued to be an area of contention between the Song dynasty and the Liao dynasty. Later the Southern Song dynasty abandoned all of North China, including Shanxi, to the Jurchen Jin dynasty (1115–1234) in 1127 after the Jingkang Incident of the Jin-Song wars.

The Mongol Yuan dynasty administered China into provinces but did not establish Shanxi as a province. Shanxi only gained its present name and approximate borders during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) which were of the same land area and borders as the previous Hedong Commandery of the Tang dynasty.

During the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Shanxi extended north beyond the Great Wall to include parts of Inner Mongolia, including what is now the city of Hohhot, and overlapped with the jurisdiction of the Eight Banners and the Guihua Tümed banner in that area.

For centuries, Shanxi served as a center for trade and banking. The "Shanxi merchants" were once synonymous with wealth.[9] The well-preserved city and UNESCO World Heritage Site Pingyao shows many signs of its economic importance during the Qing dynasty.

Early Republic of China (1912–1937)

[edit]

With the collapse of the Qing dynasty, Shanxi became part of the newly established Republic of China. From 1911 to 1949, during the period of the Republic of China's period of rule over Mainland China, Shanxi was mostly dominated by the warlord Yan Xishan until the Chinese Communist Party took full control in 1949;[10] Communists had already set up secret bases in 1936, but did not completely overturn Yan and the Nationalist government until 1949.[11] Early in Yan's rule he decided that, unless he was able to modernize and revive the economy of his small, poor, remote province, he would be unable to protect Shanxi from rival warlords. Yan devoted himself to modernizing Shanxi and developing its resources during his reign over the province. He has been viewed by Western biographers as a transitional figure who advocated using Western technology to protect Chinese traditions, while at the same time reforming older political, social and economic conditions in a way that paved the way for the radical changes that would occur after his rule.[12]

In 1918 there was an outbreak of bubonic plague in northern Shanxi that lasted for two months and killed 2,664 people. Yan's interactions with the Western medical personnel he met with to discuss how to suppress the epidemic inspired him to modernize and improve Shanxi's medical infrastructure which he began by funding the Research Society for the Advancement of Chinese Medicine, based in Taiyuan, in 1921. Highly unusual in China at the time, the school had a four-year curriculum and included courses in both Chinese and Western Medicine. The main skills that Yan hoped physicians trained at the school would learn were: a standardized system of diagnosis; sanitary science, including bacteriology; surgical skills, including obstetrics; and, the use of diagnostic instruments. Yan hoped that his support of the school would eventually lead to increased revenues in the domestic and international trade of Chinese drugs, improved public health, and improved public education. Yan's promotion of a modern curriculum and infrastructure of Chinese medicine achieved limited success, but much of the teaching and publication that this school of medicine produced was limited to the area around Taiyuan: by 1949 three of the seven government-run hospitals were in the city. In 1934 the province produced a ten-year-plan that envisaged employing a hygiene worker in every village, but the Japanese invasion in 1937 and the subsequent civil war made it impossible to carry these plans out. Yan's generous support for the Research Association for the Improvement of Chinese Medicine generated a body of teaching and publication in modern Chinese medicine that became one of the foundations of the national institution of modern traditional Chinese medicine that was adopted in the 1950s.[13]

Yan invested in Shanxi's industrial infrastructure, and by 1949 the area around Taiyuan was a major national producer of coal, iron, chemicals, and munitions.[14] Yan was able to protect the province from his rivals for the period of his rule partially due to his building of an arsenal in Taiyuan that, for the entire period of his administration, remained the only center in China capable of producing field artillery. Yan's army was successful in eradicating banditry in Shanxi, allowing him to maintain a relatively high level of public order and security.[15]

Yan went to great lengths to eradicate social traditions which he considered antiquated. He insisted that all men in Shanxi abandon their Qing-era queues, giving police instructions to clip off the queues of anyone still wearing them. In one instance, Yan lured people into theatres in order to have his police systematically cut the hair of the audience.[15] He attempted to combat widespread female illiteracy by creating in each district at least one vocational school in which peasant girls could be given a primary-school education and taught domestic skills. After National Revolutionary Army military victories in the 1925 generated great interest in Shanxi for the Kuomintang's ideology, including women's rights, Yan allowed girls to enroll in middle school and college, where they promptly formed a women's association.[16]

Yan attempted to eradicate the custom of foot binding, threatening to sentence men who married women with bound feet, and mothers who bound their daughters' feet, to hard labor in state-run factories. He discouraged the use of the traditional lunar calendar and encouraged the development of local boy scout organizations. Like the Communists who later succeeded Yan, he punished habitual lawbreakers to "redemption through labour" in state-run factories.[15]

After the failed attempt by the Chinese Red Army to establish bases in southern Shanxi in early 1936 Yan became convinced that the Communists were lesser threats to his rule than either the Nationalists or the Japanese. He then negotiated a secret anti-Japanese "United Front" with the Communists in October 1936 and invited them to establish operations in Shanxi. Yan, under the slogan "resistance against the enemy and defense of the soil", attempted to recruit young, patriotic intellectuals to his government in order to organize a local resistance to the threat of Japanese invasion. By the end of 1936 Taiyuan had become a gathering point for anti-Japanese intellectuals from all over China.[17]

War with Japan and the Chinese Civil War (1937–1949)

[edit]The Marco Polo Bridge Incident in July 1937 led the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces to invade China, and Shanxi was one of the first areas the Japanese attacked. When it became clear to Yan that his forces might not be successful in repelling the Imperial Japanese Army, he invited Communist military forces to re-enter Shanxi. Zhu De became the commander of the Eighth Route Army active in Shanxi and was named the vice-commander of the Second War Zone, under Yan himself. Yan initially responded warmly to the re-entry of the arrival of Communist forces, and they were greeted with enthusiasm by Yan's officials and officers. Communist forces arrived in Shanxi just in time to help defeat a decisively more powerful Japanese force attempting to move through the strategic Pingxing Pass. The Battle of Pingxingguan was the largest battle won by the Communists against the Japanese.[18]

After the Japanese responded to this defeat by outflanking the defenders and moving towards Taiyuan, the Communists avoided decisive battles and mostly attempted to harass Japanese forces and sabotage Japanese lines of supply and communication. The Japanese suffered, but mostly ignored the Eighth Route Army and continued to advance towards Yan's capital. The lack of attention directed at their forces gave the Communists time to recruit and propagandize among the local peasant populations (who generally welcomed Communist forces enthusiastically) and to organize a network of militia units, local guerrilla bands and popular mass organizations.[18]

Genuine Communist efforts to resist the Japanese gave them the authority to carry out sweeping and radical social and economic reforms, mostly related to land and wealth redistribution, which they defended by labeling those who resisted as Hanjian. Communist efforts to resist the Japanese also won over Shanxi's small population of patriotic intellectuals, and conservative fears of resisting them effectively gave the Communists unlimited access to the rural population. Subsequent atrocities committed by the Japanese in the effort to rid Shanxi of Communist guerrillas aroused the hatred of millions in the Shanxi countryside, causing the rural population to turn to the Communists for leadership against the Japanese. All of these factors explain how, within a year of re-entering Shanxi, the Communists were able to take control of most of Shanxi not firmly held by the Japanese.[19]

During the Battle of Xinkou, the Chinese defenders resisted the efforts of Japan's elite Itakagi Division for over a month, despite Japanese advantages in artillery and air support. By the end of October 1937, Japan's losses were four times greater than those suffered at Pingxingguan, and the Itakagi Division was close to defeat. Contemporary Communist accounts called the battle "the most fierce in North China", while Japanese accounts called the battle a "stalemate". In an effort to save their forces at Xinkou, Japanese forces began an effort to occupy Shanxi from a second direction, in the east. After a week of fighting, Japanese forces captured the strategic Niangzi Pass, opening the way to capturing Taiyuan. Communist guerrilla tactics were ineffective in slowing down the Japanese advance. The defenders at Xinkou, realizing that they were in danger of being outflanked, withdrew southward, past Taiyuan, leaving a small force of 6,000 men to hold off the entire Japanese army. A representative of the Japanese Army, speaking of the final defense of Taiyuan, said that "nowhere in China have the Chinese fought so obstinately".[20]

The Japanese suffered 30,000 dead and an equal number wounded in their effort to take northern Shanxi. A Japanese study found that the battles of Pingxingguan, Xinkou, and Taiyuan were responsible for over half of all the casualties suffered by the Japanese army in North China. Yan himself was forced to withdraw after having 90% of his army destroyed, including a large force of reinforcements sent into Shanxi by the central government. Throughout 1937, numerous high-ranking Communist leaders, including Mao Zedong, lavished praise on Yan for waging an uncompromising campaign of resistance against the Japanese. Possibly because of the severity of his losses in northern Shanxi, Yan abandoned a plan of defense based on positional warfare, and began to reform his army as a force capable of waging guerrilla warfare. After 1938 most of Yan's followers came to refer to his regime as a "guerrilla administration".[21]

After the surrender of Japan and the end of the Second World War, Yan Xishan was notable for his ability to recruit thousands of Japanese soldiers stationed in northwest Shanxi in 1945, including their commanding officers, into his army. By recruiting the Japanese into his service in the manner that he did, he retained both the extensive industrial complex around Taiyuan and virtually all of the managerial and technical personnel employed by the Japanese to run it. Yan was so successful in convincing surrendered Japanese to work for him that, as word spread to other areas of north China, Japanese soldiers from those areas began to converge on Taiyuan to serve his government and army. At its greatest strength the Japanese "special forces" under Yan totaled 15,000 troops, plus an officer corps that was distributed throughout Yan's army. These numbers were reduced to 10,000 after serious American efforts to repatriate the Japanese were partially successful. Yan's Japanese army was instrumental in helping him to retain control of most of northern Shanxi during much of the subsequent Chinese Civil War, but by 1949 casualties had reduced the number of Japanese soldiers under Yan's command to 3,000. The leader of the Japanese under Yan's command, Hosaku Imamura, committed suicide on the day that Taiyuan fell to Communist forces.[22]

Yan Xishan himself (along with most of the provincial treasury) was airlifted out of Taiyuan in March 1949. Shortly afterwards Republic of China Air Force planes stopped dropping food and supplies for the defenders due to fears of being shot down by the advancing Communists.[23] The People's Liberation Army, depending largely on their reinforcements of artillery, launched a major assault on April 20, 1949, and succeeded in taking all positions surrounding Taiyuan by April 22. A subsequent appeal to the defenders to surrender was refused. On the morning of April 22, 1949, the PLA bombarded Taiyuan with 1,300 pieces of artillery and breached the city's walls, initiating bloody street-to-street fighting for control of the city. At 10:00 am, April 22, the Taiyuan Campaign ended with the Communists in complete control of Shanxi. Total Nationalist casualties amounted to all 145,000 defenders, many of whom were taken as POWs. The Communists lost 45,000 men and an unknown number of civilian laborers they had drafted, all of whom were either killed or injured.[24]

The fall of Taiyuan was one of the few examples in the Chinese Civil War in which Nationalist forces echoed the defeated Ming loyalists who had, in the 17th century, brought entire cities to ruins resisting the invading Manchus. Many Nationalist officers were reported to have committed suicide when the city fell. The dead included Yan's nephew-in-law, who was serving as governor, and his cousin, who ran his household. Liang Huazhi, the head of Yan's "Patriotic Sacrifice League", had fought for years against the Communists in Shanxi until he was finally trapped in the massively fortified city of Taiyuan. For six months Liang put up a fierce resistance, leading both Yan's remaining Republic of China Army forces and his thousands of Japanese mercenaries. When Communist troops finally broke into the city and began to occupy large sections of it, Liang barricaded himself inside a large, fortified prison complex filled with Communist prisoners. In a final act of desperation, Liang set fire to the prison and committed suicide as the entire compound burned to the ground.[24]

People's Republic of China (1949–present)

[edit]Soon after the Chinese Communist Revolution, Mao Zedong assigned Kang Sheng to carry out land reform in Shanxi. Kang encouraged the populace to have numerous farmers from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds denounced as "landlords," beaten, arrested, and executed. In some areas of the province as many as one in five residents were denounced as landlords, and his program was copied throughout the rest of the new People's Republic of China.[25] Shanxi became the site of Mao's "model brigade" of Dazhai: a utopian communist scheme in Xiyang County that was supposed to be the model for all other peasants in China to emulate. If the people of Dazhai were especially suited for such an experiment, it is possible that decades of Yan's socialist indoctrination may have prepared the people of Shanxi for Communist rule. After the death of Mao, the experiment was discontinued, and most peasants reverted to private farming under post-Maoist economic reforms.[26]

Geography

[edit]Shanxi is located on a plateau made up of higher ground to the east (Taihang Mountains) and the west (Lüliang Mountains) and a series of valleys in the center through which the Fen River runs. The highest peak is Mount Wutai (Wutai Shan) in northeastern Shanxi with an altitude of 3,058 m. The Great Wall of China forms most of the northern border with Inner Mongolia. The Zhongtiao Mountains run along part of the southern border and separate Shanxi from the east–west part of the Yellow River. Mount Hua is to the southwest.

The Yellow River forms the western border of Shanxi with Shaanxi. The Fen and Qin rivers, tributaries of the Yellow River, run north-to-south through the province, and drain much of its area. The north of the province is drained by tributaries of the Hai River, such as Sanggan and Hutuo rivers. The largest natural lake in Shanxi is Xiechi Lake, a salt lake near Yuncheng in southwestern Shanxi.

Shanxi has a continental monsoon climate, and is rather arid. Average January temperatures are below 0 °C, while average July temperatures are around 21–26 °C. Winters are long, dry, and cold, while summer is warm and humid. Spring is extremely dry and prone to dust storms. Shanxi is one of the sunniest parts of China; early summer heat waves are common. Annual precipitation averages around 350 to 700 millimetres (14 to 28 in), with 60% of it concentrated between June and August.[27]

Major cities:

The outline of Shanxi's territory is a parallelogram that runs from southwest to northeast. It is a typical mountain plateau widely covered by loess. The terrain is high in the northeast and low in the southwest. The interior of the plateau is undulating, the valleys are vertical and horizontal, and the types of landforms are complex and diverse. There are mountains, hills, terraces, plains, and rivers. The area of mountains and hills accounts for 80.1% of the total area of the province, and the area of Pingchuan and river valleys accounts for 19.9% of the total area. Most of the province's altitude is above 1,500 meters, and the highest point is the Yedoufeng, the main peak of Wutai Mountain, with an altitude of 3061.1 meters, which is the highest peak in northern China.[27]

Climate

[edit]Shanxi is located in the inland of the mid-latitude zone and belongs to the temperate continental monsoon climate in terms of climate type. Due to the influence of solar radiation, monsoon circulation and geographical factors, Shanxi's climate has four distinct seasons, synchronous rain and heat, sufficient sunshine, significant climate difference between north and south, wide temperature difference between winter and summer, and large temperature difference between day and night. The annual average temperature in Shanxi Province is between 4.2 and 14.2 °C. The overall distribution trend is from north to south and from basin to high mountain. The annual precipitation in the whole province is between 358 and 621 mm, and the seasonal distribution is uneven. In June–August, the precipitation is relatively concentrated, accounting for about 60% of the annual precipitation, and the precipitation distribution in the province is greatly affected by the terrain.[27]

Area

[edit]The province has a length of 682 km (424 mi) and a width of 385 km (239 mi) from east to west, with a total area of 156,700 km2 (60,500 sq mi), accounting for 1.6% of the country's total area.[27]

Administrative divisions

[edit]Shanxi is divided into eleven prefecture-level divisions: all prefecture-level cities:

| Administrative divisions of Shanxi | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division code[28] | Division | Area in km2[29] | Population 2010[30] | Seat | Divisions[31] | |||

| Districts | Counties | CL cities | ||||||

| 140000 | Shanxi Province | 156,000.00 | 35,712,111 | Taiyuan city | 26 | 80 | 11 | |

| 140100 | Taiyuan city | 6,909.96 | 4,201,591 | Xinghualing District | 6 | 3 | 1 | |

| 140200 | Datong city | 14,102.01 | 3,318,057 | Pingcheng District | 4 | 6 | ||

| 140300 | Yangquan city | 4,569.91 | 1,368,502 | Cheng District | 3 | 2 | ||

| 140400 | Changzhi city | 13,957.84 | 3,334,564 | Luzhou District | 4 | 8 | ||

| 140500 | Jincheng city | 9,420.43 | 2,279,151 | Cheng District | 1 | 4 | 1 | |

| 140600 | Shuozhou city | 10,624.35 | 1,714,857 | Shuocheng District | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| 140700 | Jinzhong city | 16,386.34 | 3,249,425 | Yuci District | 2 | 8 | 1 | |

| 140800 | Yuncheng city | 14,106.66 | 5,134,794 | Yanhu District | 1 | 10 | 2 | |

| 140900 | Xinzhou city | 25,150.69 | 3,067,501 | Xinfu District | 1 | 12 | 1 | |

| 141000 | Linfen city | 20,589.11 | 4,316,612 | Yaodu District | 1 | 14 | 2 | |

| 141100 | Lvliang city | 21,143.71 | 3,727,057 | Lishi District | 1 | 10 | 2 | |

| Administrative divisions in Chinese and varieties of romanizations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Chinese | Pinyin | Jin Romanization | |

| Shanxi Province | 山西省 | Shānxī Shěng | sä̃1 śi1 sǝŋ2 | |

| Taiyuan city | 太原市 | Tàiyuán Shì | thai3 yɛ1 si3 | |

| Datong city | 大同市 | Dàtóng Shì | ta3 thuŋ1 si3 | |

| Yangquan city | 阳泉市 | Yángquán Shì | iã1 ćhyɛ1 si3 | |

| Changzhi city | 长治市 | Chángzhì Shì | cã2 ci3 si3 | |

| Jincheng city | 晋城市 | Jìnchéng Shì | tieŋ4 chǝŋ1 si3 | |

| Shuozhou city | 朔州市 | Shuòzhōu Shì | ? cou1 si3 | |

| Jinzhong city | 晋中市 | Jìnzhōng Shì | tieŋ4 cuŋ1 si3 | |

| Yuncheng city | 运城市 | Yùnchéng Shì | yŋ3 chǝŋ1 si3 | |

| Xinzhou city | 忻州市 | Xīnzhōu Shì | ? cou1 si3 | |

| Linfen city | 临汾市 | Línfén Shì | ? ? si3 | |

| Lüliang city | 吕梁市 | Lǚliáng Shì | ly2 ? si3 | |

The 11 prefecture-level cities of Shanxi are subdivided into 118 county-level divisions (23 districts, 11 county-level cities, and 84 counties). Those are in turn divided into 1388 township-level divisions (561 towns, 634 townships, and 193 subdistricts). At the end of 2017, the total population of Shanxi is 37.02 million.[32]

Urban areas

[edit]| Population by urban areas of prefecture & county cities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Cities | 2020 Urban area[33] | 2010 Urban area[34] | 2020 City proper |

| 1 | Taiyuan | 4,071,075 | 3,154,157 | 5,304,061 |

| 2 | Datong | 1,792,696 | 1,362,314[b] | 3,105,591 |

| 3 | Changzhi | 1,168,042 | 653,125[c] | 3,180,884 |

| 4 | Jinzhong | 900,569 | 444,002[d] | 3,379,498 |

| 5 | Linfen | 696,393 | 571,237 | 3,976,481 |

| 6 | Yuncheng | 692,003 | 432,554 | 4,774,508 |

| 7 | Yangquan | 647,272 | 623,671 | 1,318,505 |

| 8 | Jincheng | 574,665 | 476,945 | 2,194,545 |

| 9 | Shuozhou | 420,829 | 381,566 | 1,593,444 |

| 10 | Xinzhou | 384,424 | 279,875 | 2,689,668 |

| 11 | Xiaoyi | 337,489 | 268,253 | see Lüliang |

| 12 | Lüliang | 335,285 | 250,080 | 3,398,431 |

| 13 | Jiexiu | 291,393 | 232,269 | see Jinzhong |

| 14 | Huairen | 247,612 | [e] | see Shuozhou |

| 15 | Gaoping | 243,544 | 213,460 | see Jincheng |

| 16 | Yuanping | 227,046 | 202,562 | see Xinzhou |

| 17 | Hejin | 225,809 | 175,824 | see Yuncheng |

| 18 | Fenyang | 207,473 | 149,222 | see Lüliang |

| 19 | Huozhou | 183,575 | 156,853 | see Linfen |

| 20 | Yongji | 182,248 | 179,028 | see Yuncheng |

| 21 | Houma | 175,373 | 137,020 | see Linfen |

| 22 | Gujiao | 159,593 | 146,161 | see Taiyuan |

| — | Lucheng | see Changzhi | 106,077[c] | see Changzhi |

- ^ /ʃænˈʃiː/;[5] Chinese: ; formerly romanised as Shansi

- ^ New district established after 2010 census: Yunzhou (Datong County). The new district not included in the urban area count of the pre-expanded city.

- ^ a b New districts established after 2010 census: Lucheng (Lucheng CLC), Shangdang (Changzhi County), Tunliu (Tunliu County). These new districts not included in the urban area count of the pre-expanded city.

- ^ New district established after 2010 census: Taigu (Taigu County). The new district not included in the urban area count of the pre-expanded city.

- ^ Huairen County is currently known as Huairen CLC after 2010 census.

Most populous cities in Shanxi

Source: China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbook 2018 Urban Population and Urban Temporary Population[35] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Pop. | Rank | Pop. | ||||||

Taiyuan  Datong |

1 | Taiyuan | 3,979,700 | 11 | Xiaoyi | 295,900 |  Changzhi  Yangquan | ||

| 2 | Datong | 1,272,800 | 12 | Lüliang | 279,000 | ||||

| 3 | Changzhi | 754,800 | 13 | Jiexiu | 222,300 | ||||

| 4 | Yangquan | 638,800 | 14 | Hejin | 220,000 | ||||

| 5 | Linfen | 617,000 | 15 | Yuanping | 188,600 | ||||

| 6 | Yuncheng | 570,000 | 16 | Yongji | 171,000 | ||||

| 7 | Jinzhong | 562,800 | 17 | Gujiao | 163,000 | ||||

| 8 | Jincheng | 498,000 | 18 | Houma | 159,800 | ||||

| 9 | Shuozhou | 434,100 | 19 | Huozhou | 150,100 | ||||

| 10 | Xinzhou | 310,000 | 20 | Gaoping | 132,000 | ||||

Politics

[edit]The Governor of Shanxi is the highest-ranking official in the People's Government of Shanxi. However, in the province's dual party-government governing system, the Governor is subordinate to the provincial Communist Party Committee Secretary (中共山西省委书记), colloquially termed the "Shanxi Party Committee Secretary". As is the case in almost all Chinese provinces, the provincial party secretary and Governor are not natives of Shanxi; rather, they are outsiders who are, in practice, appointed by the central party and government authorities.

The province went through significant political instability since 2004, due largely to the number of scandals that have hit the province on labour safety, the environment, and the interconnected nature between the provincial political establishment and big coal companies. Yu Youjun was sent by the central government in 2005 to become Governor but resigned in the wake of the Shanxi slave labour scandal in 2007. He was succeeded by Meng Xuenong, who had been previously sacked as Mayor of Beijing in the aftermath of the SARS outbreak. Meng himself was removed from office in 2008 after only a few months on the job due to the political fallout from the 2008 Shanxi mudslide. In 2008, provincial Political Consultative Conference Chair, one of the highest-ranked provincial officials, Jin Yinhuan, died in a car accident.

Since Xi Jinping's ascendancy to General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party at the 18th Party Congress, numerous highly ranked officials in Shanxi have been placed under investigation for corruption-related offenses, including four incumbent members Bai Yun, Chen Chuanping, Du Shanxue, and Nie Chunyu of the provincial Communist Party Standing Committee. They were all removed from office around August 2014. The following were also removed from office:

- Ling Zhengce, the provincial Political Consultative Conference vice-chair and the older brother of Ling Jihua;

- Ling Jihua, the province's Vice Governor Ren Runhou;

- Shen Weichen, former Taiyuan party secretary;

- Liu Suiji, Taiyuan police secretary;

- Jin Daoming, vice-chair of the provincial People's Congress;

- Wang Maoshe, Yuncheng party secretary; and

- Feng Lixiang, Datong party secretary

Thousands of Shanxi officials were disciplined during the anti-corruption campaign under Xi Jinping.[36]: 4 This necessitated a scramble to find find suitable personnel for many vacated offices.[36]: 4 In the aftermath of the 'political earthquake', party secretary Yuan Chunqing was removed from his post in September 2014, with Wang Rulin 'helicoptered' into the provincial Party Secretary office.

Economy

[edit]The GDP per capita of Shanxi is below the national average. Compared to the provinces in east China, Shanxi is less developed for many reasons. Its geographic location limits its participation in international trade, which involves mostly eastern coastal provinces. Important crops in Shanxi include wheat, maize, millet, legumes, and potatoes. The local climate and dwindling water resources limit agriculture in Shanxi.[37]

Mining-related industries are a major part of Shanxi's economy.[36]: 23 Shanxi possesses 260 billion metric tons of known coal deposits, about a third of China's total. As a result, Shanxi is a leading producer of coal in China and has more coal companies than any other province,[38] with an annual production exceeding 300 million metric tonnes. The Datong (大同), Ningwu (宁武), Xishan (西山), Hedong (河东), Qinshui (沁水), and Huoxi (霍西) coalfields are some of the most important in Shanxi. Shanxi also contains about 500 million tonnes of bauxite deposits, about a third of total Chinese bauxite reserves.[39] Industry in Shanxi is centered around heavy industries such as coal and chemical production, power generation, and metal refining.[citation needed]

As part of an effort to promote diversification in non-resource industries, since 2004, some local governments in Shanxi province have required that coal mining companies set aside funds for investing in non-coal business like agriculture and produce processing.[36]: 54 In 2006, the provincial government established a policy of "subsidizing peasants by coal" which made this diversification a provincewide requirement and encouraged local governments to develop policies like subsidies and favorable tax treatment to further encourage mining companies to invest in non-coal business.[36]: 186–187

There are countless military-related industries in Shanxi due to its geographic location and history as the former base of the Chinese Communist Party and the People's Liberation Army. Taiyuan Satellite Launch Centre, one of China's three satellite launch centers, is located in the middle of Shanxi with China's largest stockpile of nuclear missiles.

Many private corporations, in joint ventures with the state-owned mining corporations, have invested billions of dollars in the mining industry of Shanxi . Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka-shing made one of his largest investments ever in China in exploiting coal gas in Shanxi. Foreign investors include mining companies from Canada, the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, Germany and Italy.[citation needed]

The mining-related companies include Daqin Railway Co. Ltd., which runs one of the busiest and most technologically advanced railways in China, connecting Datong and Qinhuangdao exclusively for coal shipping.[citation needed] The revenue of Daqin Railway Co. Ltd. is among the highest among Shanxi companies due to its export of coal to Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia.

Shanxi's nominal GDP in 2011 was 1110.0 billion yuan (US$176.2 billion), ranked 21st in China. Its per-capita GDP was 21,544 yuan (US$3,154).[40]

Shanxi is affected by cases of bad working conditions in coal mining and other heavy industries. Thousands of workers have died every year in those industries. Cases of child labour abuse were discovered in 2011.[41][42] The central government has responded by increasing oversight, including the suspension of four coal mines in August 2021, as well as ongoing investigations in Shanxi and neighboring Shaanxi.[43]

Industrial zones

[edit]Taiyuan Economic and Technology Development Zone

[edit]Taiyuan Economic and Technology Development Zone is a state-level development zone approved by the State Council in 2001, with a planned area of 9.6 km2 (3.7 sq mi). It is only 2 km (1.2 mi) from Taiyuan Airport and 3 km (1.9 mi) from the railway station. National Highways 208 and 307 pass through the zone. So far, it has formed a "four industrial base, a professional industry park" development pattern.[44]

Taiyuan Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone

[edit]Established in 1991, Taiyuan Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone is the only state-level high-tech development zone in Shanxi, with total area of 24 km2 (9.3 sq mi). It is close to Taiyuan Wusu Airport and Highway G208. The nearest port is Tianjin.[45]

Transportation

[edit]The transport infrastructure in Shanxi is highly developed. There are many important national highways and railways that connect the province with neighboring provinces.[46]

Road

[edit]Shanxi's road hub is in the capital, Taiyuan. The major highways in province form a road network connecting all the counties. Examples of major highways are:

- Datong–Yuncheng Expressway

- Taiyuan-Jiuguan Expressway

- Beijing–Hong Kong and Macau Expressway

- Beijing–Tianjin–Tanggu Expressway

Rail

[edit]Shanxi has extensive rail infrastructure to neighboring provinces. The rail network connects to major cities Taiyuan, Shijiazhuang, Beijing, Yuanping, Baotou, Datong, Menyuan and Jiaozuo. The province also have extensive rail network to coastal cities such as Qinhuangdao, Qingdao, Yantai and Lianyungang.[46]

The province has a rail network called the Shuozhou-Huanghua Railway. It will service Shenchi county in Shanxi with Huanghua port in Hebei. It will become the second largest railway for coal transport from west to east in China.[47]

Aviation

[edit]Shanxi's main aviation transport hub is Taiyuan Wusu Airport (IATA: TYN). The airport has routes connecting Shanxi to 28 domestic cities including Beijing, Xi'an, Chengdu and Chongqing. There are international routes to Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan and Russia. There is also another airport in Datong, which has domestic routes to other mainland cities.[46][48]

Demographics

[edit]The population is mostly Han Chinese with minorities of Mongol, Manchu, and the Hui.

| Ethnic group | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Han Chinese | 32,368,083 | 99.68% |

| Hui | 61,690 | 0.19% |

| Manchu | 13,665 | 0.042% |

| Mongol | 9,446 | 0.029% |

In 2004, the birth rate was 12.36 births/1,000 population, while the death rate was 6.11 deaths/1,000 population. The sex ratio was 105.5 males/100 females.[50]

Religion

[edit]Religion in Shanxi[51][note 1]

The predominant religions in Shanxi are Chinese folk religions, Taoist traditions and Chinese Buddhism. According to surveys conducted in 2007 and 2009, 15.61% of the population believes and is involved in cults of ancestors, while 2.17% of the population identifies as Christian.[51] The reports didn't give figures for other types of religion; 82.22% of the population may be either irreligious or involved in worship of nature deities, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, folk religious sects, and small minorities of Muslims.

Military police demolished a large Christian church known as Jindengtai ("Golden Lampstand") in Linfen, Shanxi, in early January 2018.[52]

As of 2010, there were 59,709 Muslims in Shanxi.[53]

-

Chenghuangshen (City God) Temple of Pingyao.

Health

[edit]In the 2000s, the province was considered to be one of the most polluted areas in China.[38] The pollution, caused in part by heavy coal mining, has caused significant public health challenges.[54]

Culture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2013) |

Language

[edit]The dialects spoken in Shanxi have traditionally been included in the Northern or Mandarin group. Since 1985, some linguists have argued that the dialects spoken in most of the province should be treated as a top-level division called Jin, based on its preservation of the Middle Chinese entering tone (stop-final) category, unlike other dialects in northern China. These dialects are also noted for extremely complex tone sandhi systems. The dialects spoken in some areas in southwestern Shanxi near the borders with Henan and Shaanxi are classified in the Zhongyuan Mandarin subdivision of the Mandarin group.

Cuisine

[edit]Shanxi cuisine is most well known for its extensive use of vinegar as a condiment, as well as for a huge variety of noodle dishes, particularly knife-cut noodles or daoxiao mian (刀削面), which are served with a range of sauces. A dish originating from Taiyuan, the provincial capital, is Taiyuan Tounao (Chinese: 太原头脑; lit. 'Taiyuan Head'). It is a breakfast dish; a porridge-like stew made with mutton, Chinese yam (山药), lotus roots, astragalus membranaceus (黄芪; 'membranous milk vetch'), tuber onions, and yellow cooking wine for additional aroma. It can be enjoyed by dipping pieces of unleavened flatbread into the soup, and is reputed to have medicinal properties. Pingyao is famous for its unique salt beef, while the areas around Wutai Shan are known for wild mushrooms. The most popular local spirit is fenjiu, a "light fragrance" variety of baijiu that is generally sweeter than other northern Chinese spirits.

Music

[edit]Shanxi Opera (晋剧 Jinju) is the local form of Chinese opera. It was popularized during the late Qing dynasty, with the help of the then-ubiquitous Shanxi merchants who were active across parts of China. Also called Zhonglu Bangzi (中路梆子), it is a type of bangzi opera (梆子), a group of operas generally distinguished by their use of wooden clappers for rhythm and by a more energetic singing style; Shanxi opera is also complemented by quzi (曲子), a blanket term for more melodic styles from further south. Puzhou Opera (蒲剧 Puju), from southern Shanxi, is a more ancient type of bangzi that makes use of very wide linear intervals.

Ancient commerce

[edit]Shanxi merchants (晉商 Jinshang) constituted a historical phenomenon that lasted for centuries from the Song to the Qing dynasty. Shanxi merchants ranged far and wide from Central Asia to the coast of eastern China; by the Qing dynasty they were conducting trade across both sides of the Great Wall. During the late Qing dynasty, a new development occurred: the creation of piaohao (票號), which were essentially banks that provided services like money transfers and transactions, deposits, and loans. After the establishment of the first piaohao in Pingyao, the bankers in Shanxi dominated China's financial market for centuries until the collapse of Qing dynasty and the coming of British banks.

Tourism

[edit]

Shanxi is known for its abundance of heritage sites. There are 3 World Cultural Heritage sites in the province, namely Pingyao, Yungang Grottoes and Mount Wutai, 6 places "National Key Scenic Spots" (国家重点风景名胜区), 6 "National historic and cultural cities" (国家历史文化名城), 7 "National historic and cultural towns" (国家历史文化名镇) and 23 "National historic and cultural villages" (国家历史文化名村). It also possesses 531 Major Historical and Cultural Sites Protected at the National Level,and more than 53,800 immovable cultural relics, a number that is by far the greatest among all Chinese provinces. Some of the more notable sites are listed below.

- Jinci, a royal temple in Taiyuan, dating back to the Zhou dynasty, noted for its temples, Song dynasty paintings and architecture.

- The Ancient City of Pingyao is a county town noted for its noted for its state of preservation; It boasts a variety of Ming and Qing dynasties.

- The Yungang Grottoes, its literal translation being the Cloud Ridge Caves, is a World Heritage Site near Datong. The site consists of 252 shallow caves containing over 50,000 carved statues and reliefs of Buddhas and Boddhisatvas, dating from the 5th and 6th centuries, and ranging from 4 centimeters to 7 meters tall.

- Mount Wutai (Wutai Shan) is the highest point in the province. It is known as the residence of the bodhisattva Manjusri, and as a result is also a major Buddhist pilgrimage destination, with many temples and natural sights. Points of interest include Tang dynasty (618–907) era timber halls located at Nanchan Temple and Foguang Temple, as well as a giant white stupa at Tayuan Temple built during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

- Mount Hengshan (Heng Shan), in Hunyuan County, is one of the "Five Great Peaks" of China, and is also a major Taoist site. Not far from Hengshan, the Hanging Temple is located on the side of a cliff and has survived for 1,400 years despite earthquakes in the area.

- Pagoda of Fogong Temple, in Ying County, is a pagoda built in 1056 during the Liao dynasty. It is octagonal with nine levels (five are visible from outside), and at 67 m (220 ft) in height, it is currently the tallest wooden pagoda in the world. It is also the oldest fully wooden pagoda in China, although many no-longer-existing wooden pagodas have preceded it, and many existing stone and brick pagodas predate it by centuries.

- Yongle Gong, a Song dynasty Taoist temple complex noted for the wall paintings inside its three main halls.

- Hukou Waterfall is located in the Yellow River on the Shanxi-Shaanxi border. At 50 meters, it is the second highest waterfall in China.

- Zuoquan County, known for its Chinese Communist Party battlefield sites.

- Dazhai is a village in Xiyang County. Situated in hilly, difficult terrain, it was revered during the Cultural Revolution as exemplary of the hardiness of the proletariat, especially peasants.

- Niangziguan Township is located in northeast Pingding County which is at the junction of Shanxi and Heibei Province. It is an old village noted for the Niangzi Pass.

- Susan Prison is an ancient prison located in Hongtong, the middle of Shanxi. The prison is built during the Ming dynasty (1369) and is the only well-preserved ancient prison in China.[55]

Notable individuals

[edit]- Boyi and Shuqi (just after 1046 BCE), starved themselves in self-imposed exile

- King Wuling of Zhao (325 BCE-299 BCE), ruler of State of Zhao during the Warring States period

- Wei Qing (?–106 BC), military general of the Western Han dynasty whose campaigns against the Xiongnu earned him great acclaim

- Huo Qubing (140 BC–117 BC), military general of the Western Han dynasty during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han

- Huo Guang (?–106 BC), powerful official of the Western Han dynasty

- Guan Yu (?-220), general serving under Liu Bei during the late Eastern Han dynasty who was known for his superior martial prowess on the battlefield

- Zhang Liao (169–222), general serving under Cao Cao in the late Eastern Han dynasty who was known for his superior martial prowess on the battlefield

- Xu Huang (?–227), general serving under Cao Cao in the late Eastern Han dynasty

- Hao Zhao (220–229), general of the state of Cao Wei during the Three Kingdoms period of China

- Guo Huai (?–255), general of the state of Cao Wei during the Three Kingdoms period of China

- Guanqiu Jian (?–255), general of the state of Cao Wei during the Three Kingdoms period of China

- Qin Lang (227–238), general of the state of Cao Wei during the Three Kingdoms period of China

- Jia Chong (217–282), official who lived during the late Three Kingdoms period and early Jin dynasty of China

- Liu Yuan (?–310), the founding emperor of the Xiongnu state Han-Zhao in 308

- Liu Cong (?–318), emperor of the Xiongnu state Han-Zhao

- Liu Yao (?–329), the final emperor of the Xiongnu state Han-Zhao

- Shi Le (274–333), the founding emperor of the Jie state Later Zhao

- Shi Hu (295–349), emperor of the Jie state Later Zhao, he was the founding emperor Shi Le's distant nephew

- Murong Yong (?–394), the last emperor of the Xianbei state Western Yan

- Wang Sengbian (?–394), general of the Liang dynasty

- Tuoba Gui (371–409), founding emperor of the Xianbei state Northern Wei

- Tuoba Tao (408–452), an emperor of Xianbei state Northern Wei

- Erzhu Rong (493–530), general of the Chinese/Xianbei dynasty Northern Wei, He was of Xiongnu ancestry

- Erzhu Zhao (493–530), general of the Northern Wei, He was ethnically Xiongnu and a nephew of the paramount general Erzhu Rong

- Hulü Guang (515–572), general of the Chinese dynasty Northern Qi

- Dugu Xin (503–557), a paramount general of the state Western Wei

- Yuchi Jiong (?–580), a paramount general of the states Western Wei and Northern Zhou

- Yuchi Jingde (585–658), general who lived in the early Tang dynasty and is worshipped as door god in Chinese folk religion

- Wang Tong (587–618), Confucian philosopher and writer

- Xue Ju (?–618), the founding emperor of a short-lived state of Qin at the end of the Chinese dynasty Sui dynasty

- Pei Xingyan (?–619), general in Sui dynasty who was known for his superior fighting skills on the battlefield

- Xue Rengui (614–683), general in Tang dynasty who was known for his superior martial prowess on the battlefield

- Pei Xingjian (619–682), a Tang dynasty general who was best known for his victory over the Khan of Western Turkic Khaganate Ashina Duzhi

- Xue Ne (649–720), a general and official of the Tang dynasty

- Feng Changqing (?-756), a general of the Tang dynasty

- Xue Song (?-773), grandson of Xue Rengui, a general of the rebel state Yan

- Li Keyong (856–908), a Shatuo military governor (Jiedushi) during the late Tang dynasty

- Li Cunxiao (?-894), an adoptive son of Li Keyong and considered one of the strongest warriors in ancient China history

- Li Cunxu (885-926), the Prince of Jin (908–923) and later became Emperor of Later Tang (923–926)

- Li Siyuan (867–933), the second emperor of imperial China's short-lived Later Tang during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period

- Shi Jingtang (892–942), the founding emperor of imperial China's short-lived Later Jin during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period

- Huyan Zan (?-1000), a military general in the early years of imperial China's Song dynasty

- Di Qing (1008–1057), a military general of the Northern Song dynasty

Education

[edit]Major tertiary educational institutions in Shanxi include:

- North University of China (中北大学)

- Communication University of Shanxi (山西传媒大学)

- Changzhi Medical College (长治医学院)

- Datong University (山西大同大学)

- Jinzhong College (晋中学院)

- Lüliang Higher College

- Shanxi Agricultural University (山西农业大学)

- Shanxi College of Traditional Chinese Medicine (山西中医学院)

- Shanxi Medical University (山西医科大学)

- Shanxi Normal University (山西师范大学)

- Shanxi University (山西大学)

- Shanxi University of Finance and Economics (山西财经大学)

- Changzhi College (长治学院)

- Taiyuan Normal University (太原师范学院)

- Taiyuan University of Science and Technology (太原科技大学)

- Taiyuan University of Technology (太原理工大学)

- Xinzhou Teachers University (忻州师范学院)

- Yuncheng University (运城学院)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The data was collected by the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) of 2009 and by the Chinese Spiritual Life Survey (CSLS) of 2007, reported and assembled by Xiuhua Wang (2015)[51] in order to confront the proportion of people identifying with two similar social structures: ① Christian churches, and ② the traditional Chinese religion of the lineage (i. e. people believing and worshipping ancestral deities often organised into lineage "churches" and ancestral shrines). Data for other religions with a significant presence in China (deity cults, Buddhism, Taoism, folk religious sects, Islam, et al.) was not reported by Wang.

- ^ This may include:

- Buddhists;

- Confucians;

- Deity worshippers;

- Taoists;

- Members of folk religious sects;

- Small minorities of Muslims;

- And people not bounded to, nor practicing any, institutional or diffuse religion.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Geography". Shanxi Tourism Bureau. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ "Communiqué of the Seventh National Population Census (No. 3)". National Bureau of Statistics of China. 11 May 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "National Data". China NBS. March 2024. Retrieved June 22, 2024. see also "zh: 2023年山西省国民经济和社会发展统计公报". shanxi.gov.cn. March 30, 2024. Retrieved June 22, 2024. The average exchange rate of 2023 was CNY 7.0467 to 1 USD dollar "Statistical communiqué of the People's Republic of China on the 2023 national economic and social development" (Press release). China NBS. February 29, 2024. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ "Human Development Indices (8.0)- China". Global Data Lab. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "Shanxi". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021.

- ^ Wilkinson (2012), p. 234.

- ^ 地上文物看山西,太原纯阳宫"变身"山西古建筑博物馆 (in Chinese). 13 April 2020.

- ^ 《晉國史綱要》第163頁 (Jin State Compendium, page 163)

- ^ Shanxi Provincial Academy of Social Sciences, ed., Shanxi piaohao shiliao (山西票号史料) (Taiyuan: Shanxi jingji chubanshe, 1992), pp. 36–39.

- ^ Gillin The Journal of Asian Studies

- ^ Gillin Warlord 220-221

- ^ Gillin, Donald G. "Portrait of a Warlord: Yen Hsi-shan in Shansi Province, 1911–1930." The Journal of Asian Studies. Vol. 19, No. 3, May, 1960. Retrieved February 23, 2011. p.289

- ^ Harrison, Henrietta. "The Experience of Illness in Early Twentieth-Century Shanxi.". East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine. No.42. pp.39–72. 2015. pp.61–63.

- ^ Goodman, David S. G. "Structuring Local Identity: Nation, Province and County in Shanxi During the 1990s". The China Quarterly. Vol.172, December 2002. pp.837–862. Retrieved April 17, 2019. p.840

- ^ a b c Gillin, Donald G. "Portrait of a Warlord: Yen Hsi-shan in Shansi Province, 1911–1930." The Journal of Asian Studies. Vol. 19, No. 3, May, 1960. Retrieved February 23, 2011. p.295

- ^ Gillin, Donald G. Warlord: Yen Hsi-shan in Shansi Province 1911–1949. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 1967. p.24"

- ^ Feng Chongyi and Goodman, David S. G., eds. North China at War: The Social Ecology of Revolution, 1937–1945. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield. 2000. ISBN 0-8476-9938-2. Retrieved June 3, 2012. p.157-158.

- ^ a b Gillin, Donald G. Warlord: Yen Hsi-shan in Shansi Province 1911–1949. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 1967. pp. 263–264

- ^ Gillin, Donald G. Warlord: Yen Hsi-shan in Shansi Province 1911–1949. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 1967. p.271

- ^ Gillin, Donald G. Warlord: Yen Hsi-shan in Shansi Province 1911–1949. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 1967. p. 272-273

- ^ Gillin, Donald G. Warlord: Yen Hsi-shan in Shansi Province 1911–1949. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 1967. pp.273–275, 279

- ^ Gillin, Donald G. and Etter, Charles. "Staying On: Japanese Soldiers and Civilians in China, 1945–1949." The Journal of Asian Studies. Vol. 42, No. 3, May, 1983. Retrieved February 23, 2011. pp.506–508

- ^ Gillin, Donald G. Warlord: Yen Hsi-shan in Shansi Province 1911–1949. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 1967. p.288.

- ^ a b Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China, W.W. Norton and Company. 1999. p.488

- ^ Dikötter, Frank (2013). The Tragedy of Liberation: A History of the Chinese Revolution, 1945-1957 (1 ed.). London: Bloomsbury Press. pp. 72–74. ISBN 978-1-62040-347-1.

- ^ Bonavia, David. China's Warlords. New York: Oxford University Press. 1995. p.138.

- ^ a b c d 省情概貌. Shanxi People's Government. 2016-07-13.

- ^ 中华人民共和国县以上行政区划代码 (in Simplified Chinese). Ministry of Civil Affairs.

- ^ Shenzhen Statistical Bureau. 《深圳统计年鉴2014》 (in Simplified Chinese). China Statistics Print. Archived from the original on 2015-05-12. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

- ^ Census Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China; Population and Employment Statistics Division of the National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China (2012). 中国2010人口普查分乡、镇、街道资料 (1 ed.). Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-6660-2.

- ^ Ministry of Civil Affairs (August 2014). 《中国民政统计年鉴2014》 (in Simplified Chinese). China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-7130-9.

- ^ 中国统计年鉴—2018. National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China. 2018.

- ^ 国务院人口普查办公室、国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司编 (2022). 中国2020年人口普查分县资料. Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-9772-9.

- ^ 国务院人口普查办公室、国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司编 (2012). 中国2010年人口普查分县资料. Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-6659-6.

- ^ Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People's Republic of China(MOHURD) (2019). 中国城市建设统计年鉴2018 [China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbook 2018] (in Chinese). Beijing: China Statistic Publishing House.

- ^ a b c d e Zhan, Jing Vivian (2022). China's Contained Resource Curse: How Minerals Shape State-Capital-Labor Relations. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-04898-9.

- ^ Infos on Shanxi official website Archived February 20, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Shanxi Province @ The China Perspective". thechinaperspective.com. June 2, 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-06-02.

- ^ 3.9.1 Resources-China Mining Archived 2009-01-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 山西省统计局:山西省人均GDP 已达至3154美元. chinanews.com Shanxi (in Simplified Chinese). 2010-03-16.

- ^ "Chinese mine blast toll doubles". BBC News. 2009-11-22. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ "23 miners died and 53 sickened in Shanxi state-owned coal mine | China Labour Bulletin". Archived from the original on July 16, 2011.

- ^ "China's Shanxi province suspends four coal mines | Argus Media". 28 April 2021.

- ^ "RightSite.asia | Taiyuan Economic & Technology Development Zone".

- ^ "RightSite.asia | Taiyuan Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone".

- ^ a b c "Shanxi Province". www.accci.com.au.

- ^ Brief Introduction of Shuozhou Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Datong Transportation: by Air, Train, Bus and Taxi". www.travelchinaguide.com.

- ^ National Bureau of Statistics; State Ethnic Affairs Commission, eds. (2003). 《2000年人口普查中国民族人口资料》 [Tabulation on Nationalities of 2000 Population Census of China] (in Chinese (China)). Beijing: Publishing House of Minority Nationalities. ISBN 7-105-05425-5.

- ^ 山西(2004年). Archived from the original on February 21, 2006. Retrieved February 19, 2006.

- ^ a b c China General Social Survey 2009, Chinese Spiritual Life Survey (CSLS) 2007. Report by: Xiuhua Wang (2015, p. 15) Archived 2015-09-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ AFP (14 January 2018). "China demolishes Christian megachurch with explosives as religious groups decry 'Taliban-style persecution'". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

The huge evangelical Jindengtai ("Golden Lampstand") Church, painted grey and surmounted by turrets and a large red cross, was located in Linfen, Shanxi province. Its demolition began on Tuesday under "a city-wide campaign to remove illegal buildings", the Global Times newspaper reported, quoting a local government official who wished to remain anonymous.

- ^ "Muslim in China, Muslim Population & Distribution & Minority in China". www.topchinatravel.com. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ Disabilities in China's polluted Shanxi, 2009

- ^ 原化周. (1996). 一座完整的明代监狱——苏三监狱. 上海集邮 / Shanghai Philately, 6, 11.http://lib.cqvip.com/qk/80553X/199606/4001179067.html

Sources

[edit]- Wilkinson, Endymion (2012). Chinese History: A New Manual. Harvard–Yenching Institute Monograph Series. Vol. 84. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-06715-8.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in Chinese)

- Economic profile for Shanxi at HKTDC

- Shanxi Community of Canada website (in Chinese)

- "Geographic Surveys by Imperial Order", from 1707 to 1708, is considered one of the first atlases of the Qing dynasty to document the Shanxi area.