Women's rights in Saudi Arabia

| General Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 12 (2015)[1] |

| Women in parliament | 19.9% (2016)[2] |

| Women over 25 with secondary education | 77.2% (2020)[3] |

| Women in labour force | 37.0% (2022)[4] |

| Gender Inequality Index[5] (2021) | |

| Value | 0.247 |

| Rank | 59th out of 191 |

| Global Gender Gap Index[6] (2022) | |

| Value | 0.636 |

| Rank | 127th out of 146 |

Women in Saudi Arabia experience widespread discrimination in Saudi politics, economy and society. They have benefited from some legal reforms since 2017,[7][8][9][10] after facing fundamentalist Sahwa dominance for decades.[11][12] According to Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, Saudi women are still discriminated against in terms to marriage, family, and divorce despite the reforms,[13][14] and the Saudi government continues to target and repress women's rights activists and movements.[15] Prominent feminist campaigns include the Women to Drive Movement[16] and the anti male-guardianship campaign,[17][18] which have led to significant advances in women's rights.[19]

Women's societal roles in Saudi Arabia are heavily affected by Islamic and local traditions of the Arabian Peninsula. Wahhabism, the Hanbali school of Sunni Islam, traditions of the Arabian Peninsula and national and local laws all impact women's rights in Saudi Arabia.[20]

Rankings

[edit]The World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap Report 2024 ranked Saudi Arabia as number 126 out of 146 countries, exceeding countries such as Turkey and Lebanon.[21] However, in the World Bank's 2021 Women, Business, and the Law index, Saudi Arabia scored 80 out of 100, an above-average global score.[22][23] The United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) elected Saudi Arabia to the U.N. Commission on the Status of Women for 2018 to 2022, a move that was widely criticized internationally.[24][25] According to the World Bank, Saudi Arabia has been making significant improvements to women's working conditions since 2017, addressing issues of mobility, sexual harassment, pensions, and workplace rights including employment discrimination protection.[26][27]

Timeline of female empowerment

[edit]- In 1955, Queen Iffat opened the first private school for girls in Jeddah.[28]

- In 1960, King Saud issued a royal decree that made state schools accessible for girls all around the country.[29]

- In 1970, the first higher education institution for women was founded.[30]

- In 1999, Saudi Arabia agreed to issue women national ID cards.[31]

- In 2005, Saudi Arabia banned forced marriages.[32]

- In 2009, the first Saudi female minister was appointed to the Cabinet.[33]

- In 2011, King Abdullah made provision for women to vote for the first time, in the 2015 local elections and to be appointed to the Consultative Assembly, the national legislature.[34]

- In 2012, Saudi women were allowed to compete in the Summer Olympics for the first time.[35]

- In 2013, women were permitted to ride motorbikes and bicycles in recreational areas.[36]

- Since 2013, the Consultative Assembly has required that women must hold at least 20% of seats.[37]

- In February 2017, Saudi Arabia appointed the first woman to chair the national stock exchange, the largest stock market in the Middle East.[38]

- In May 2017, King Salman ordered that women should be allowed access to government services, such as education and healthcare, without needing consent from a male guardian.[39]

- In September 2017, King Salman issued a decree allowing women to drive, lifting the decades-old ban on female drivers.[40]

- As of October 2017, women were allowed into sport stadiums.[41]

- In 2018, public statements by crown prince Mohammed bin Salman and legislation restricting the powers of the religious police led many Saudi women to abandon wearing hijab in public.[42][43]

- In November 2018, the Saudi government issued a resolution that prohibits wage discrimination for women who perform work similar to their male counterparts in the private sector.[44]

- In January 2019, the Saudi Supreme Court issued a law requiring courts to notify women of divorce via text. Previously, guardian laws allowed men to divorce their wives without notice,[45] a policy that left many women disorientated and homeless.

- As of 1 August 2019, women have the right to register for divorce and marriage, apply for passports and other official documents, and travel abroad without their guardian's permission.[46][47] The laws also extend employment discrimination protections to women, allow them to register as co-head of a household, live independently from their husband, and become eligible for the guardianship of minors.[48][49]

- In October 2019, the Saudi Ministry of Defense stated that women can join the senior ranks of the military.[50]

- In December 2019, the Saudi government banned marriage for under-18s of both sexes.[51][52]

- In August 2020, the Saudi Cabinet approved an amendment that deletes the articles which prohibited women from working at night and working in hazardous jobs and industries.[53][44]

- As of January 2021, women can now change their personal data, such as their family name, name of children, and their marital status, without a guardian's permission.[54]

- Beginning in June 2021, Saudi Arabia allowed single, divorced, or widowed women to live independently without permission from their male guardians.[55][56]

- As of July 2021, the Saudi Ministry of Hajj and Umrah has allowed women to register to perform the Hajj without being accompanied by a mahram.[57]

- In February 2022, the Saudi Arabia women's national football team competed in, and won, their first ever international match, a friendly against the Seychelles by the score of 2–0 in Malé, Maldives.[58]

- In March 2022, Muslim women over the age of 45 were allowed to perform the Umrah without a male guardian.[59] Shortly thereafter, a new decision was announced allowing Muslim women under 45 years old to travel without a male guardian to perform both the Hajj and Umrah rites.[60][61]

- In July 2022, the first woman deputy secretary-general of the Saudi Cabinet was appointed.[62]

- In September 2022, Saudi Arabia appointed the first woman to chair the Saudi Human Rights Commission.[63]

- On 22 September 2022, Saudi Arabia announced it would send its first woman into space in early 2023 as part of the Saudi Space Commission's new space program.[64][65]

- On 5 January 2023, FIFA appointed the first female Saudi international referee.[66][67]

- On 11 January 2023, King Salman approved an amendment of the Saudi nationality law that allows Saudi women married to foreign men to pass on Saudi citizenship to their children. This represents a major change to the kingdom's citizenship laws, and it has been debated since 2016.[68][69]

Background

[edit]Gender roles in Saudi society come from local culture and interpretations of Sharia law, or the divine will. Scholars of the Quran and hadith (sayings and accounts of Muhammad's life) derive its interpretations. In Saudi culture, the Sharia is interpreted according to a strict Sunni Islam form known as the way of the Salaf (righteous predecessors) or Wahhabism. The law is mostly unwritten, leaving judges with significant discretionary power, which they usually exercise in favor of tribal traditions.[70] Activists such as Wajeha al-Huwaider compared the condition of Saudi women in 2007 to slavery.[71]

Varying interpretations have led to controversy. For example, Sheikh Ahmed Qassim Al-Ghamdi, chief of the Mecca region's Islamic religious police, the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, also known as the mutaween, has said that Sharia does not prohibit ikhtilat (gender mixing).[72][73] Meanwhile, Abdul-Rahman al-Barrak, another prominent cleric, issued a fatwa stating that proponents of ikhtilat should be killed.[74]

According to the Encyclopedia of Human Rights, sex segregation is a key aspect of Islamic legal theory used to curtail women's rights. The Sharia legal notion of 'shielding from corruption' (dar al-fasaad) justifies this segregation.

Many Saudis do not see Islam itself as the main impediment to women's rights, and "It's the culture, not the religion" is a common Saudi saying.[75] According to the Library of Congress, customs of the Arabian peninsula also affect women's places in Saudi society. The peninsula is the ancestral home of patriarchal, nomadic tribes, in which separation of women and men, and namus (honour), are considered central.[citation needed] According to one female journalist, "If the Qu'ran does not address the subject, then the clerics will err on the side of caution and make it haram [forbidden]. The driving ban for women is the best example."[72] Sabria Jawhar has stated, "if all women were given the rights the Qu'ran guarantees us, and not be supplanted by tribal customs, then the issue of whether Saudi women have equal rights would be reduced."[76][77]

Saudis often invoke the life of Muhammad to prove that Islam allows for strong women. His first wife, Khadijah, was a powerful businesswoman who employed him and proposed marriage on her own.[78] His wife Aisha commanded an army at the Battle of Bassorah and is the source of many hadiths.[79][80]

The level of enforcement of various rules can vary by region: Jeddah is relatively permissive, while Riyadh and the surrounding Najd region, origin of the House of Saud, have stricter traditions.[81]

Enforcement of the Kingdom's strict moral code, including hijab and separation of the sexes, is often handled by the mutaween (also Hai'a)—a special committee of Saudi men sometimes called "religious police." Mutaween have some law enforcement powers. For example, mutaween have the power to detain Saudi citizens or resident foreigners for doing anything deemed immoral. While the anti-vice committee is active across the Kingdom, it is particularly active in Riyadh, Buraydah and Tabuk.

History

[edit]Until the Islamic revivalism, which occurred in Saudi Arabia after the Grand Mosque seizure in 1979, there were no legal requirement for women's veiling or seclusion. In the King Faisal era (1964–1975), women's access to education, work and public visibility expanded, and in the 1970s, some Saudi women did not veil in public.[82][83]

The 1979 Iranian Revolution and subsequent Grand Mosque Seizure in Saudi Arabia caused the government to implement stricter enforcement of Sharia. Saudi women who were adults before 1979 recall driving, inviting unrelated men into their homes (with the door open), and being in public without an abaya or niqab.[72][84] 1979 was also a pivotal year for the emergence of women's roles in Saudi music, art, and culture.[85] The subsequent September 11th attacks against the World Trade Center in 2001, on the other hand, are often viewed as precipitating cultural change away from strict fundamentalism.[76][79][86]

The government under King Abdullah was considered reformist. It opened the country's first co-educational university, appointed the first female cabinet member, and passed laws against domestic violence. Women did not gain the right to vote until 2005, but the king supported women's right to drive and vote. Critics say the reforms were far too slow and often more symbolic than substantive.[86][87][88]

Public opinion

[edit]According to The Economist, a 2006 Saudi government poll found that 89% of Saudi women did not think women should drive, and 86% did not think women should work with men.[89] However, this was directly contradicted by a 2007 Gallup poll, which found that 66% of Saudi women and 55% of Saudi men agreed that women should be allowed to drive.[90] Moreover, that same poll found that more than 8 in 10 Saudi women (82%) and three-quarters of Saudi men (75%) agreed that women should be allowed to hold any job for which they are qualified.[90]

500 Saudi women attended a 2006 lecture in Riyadh that opposed loosening traditional gender roles and restrictions. Mashael al-Eissa, a writer, opposed reforms. She argued that Saudi Arabia is the closest thing to an ideal and pure Islamic nation, and that it is under threat from "imported Western values."[91]

In 2013, former lecturer Ahmed Abdel-Raheem polled female students at Al-Lith College for Girls at Umm al-Qura University in Mecca and found that 79% of the participants opposed lifting the driving ban for women. One of the students who took part in the poll commented, "In my point of view, female driving is not a necessity because in the country of the two holy mosques every woman is like a queen. There is [someone] who cares about her; and a woman needs nothing as long as there is a man who loves her and meets her needs; as for the current campaigns calling for women's driving, they are not reasonable. Female driving is a matter of fun and amusement, let us be reasonable and thank God so much for the welfare we live in."[92]

Abdel-Raheem conducted another poll of 8,402 Saudi women, which found that 90% of women supported the male guardianship system.[93] Another poll conducted by Saudi students found that 86% of Saudi women do not want the driving ban to be lifted.[92] A Gallup poll in 2006, conducted in eight predominantly Muslim countries, found that only in Saudi Arabia did the majority of women disagree that women should be allowed to hold political office.[94]

Some Saudi women, including educated ones, who have been supportive of traditional gender roles, have insisted that loosening the bans on women driving and working with men is part of an onslaught of Westernized ideas meant to weaken Islam.[91] Many have also taken the position that Saudi Arabia is uniquely in need of conservative values because it is the center of Islam.[91] Some Saudi female advocates of government reform reject foreign criticism of Saudi limitations upon rights for "failing to understand the uniqueness of Saudi society."[91][74][86]

Journalist Maha Akeel, a frequent critic of her government's restrictions on women, states that Western critics do not understand Saudi Arabia. "Look, we are not asking for... women's rights according to Western values or lifestyles... We want things according to what Islam says. Look at our history, our role models."[79] According to former Arab News managing editor John R. Bradley, Western pressure for broadened rights is counterproductive, particularly pressure from the United States, given the "intense anti-American sentiment in Saudi Arabia after September 11."[95]

Male guardianship

[edit]Under previous Saudi law, all females were required to have a male guardian (wali), typically a father, brother, husband, or uncle (mahram). In 2019, this law was partially amended to exclude women over 21 years old from the requirement of a male guardian.[46] The new amendment also granted women rights in relation to the guardianship of minor children.[46][47] Previously, girls and women were forbidden from traveling, conducting official business, or undergoing certain medical procedures without permission from their male guardians.[96] In 2019, Saudi Arabia allowed women to travel abroad, register for divorce or marriage, and apply for official documents without the permission of a male guardian.

Male guardians have duties to, and rights over, women in many aspects of civic life. A United Nations Special Rapporteur document states:

Legal guardianship of women by a male is practiced in varying degrees and encompasses major aspects of women's lives. The system is said to emanate from social conventions, including the importance of protecting women, and from religious precepts on travel and marriage, although these requirements were arguably confined to particular situations.[70]

The official law, if not the custom, requiring a guardian's permission for a woman to seek employment was repealed in 2008.[74][97][98][99][100]

In 2012, the Saudi government implemented a new policy to help enforce these traveling restrictions for women. Under it, Saudi Arabian men receive a text message on their mobile phones whenever a woman under their custody leaves the country, even if she is traveling with her guardian. Saudi Arabian feminist activist Manal al-Sharif commented that "[t]his is technology used to serve backwardness in order to keep women imprisoned."[101]

Every year more than 1,000 women try to flee Saudi Arabia. Text alerts sent by the Saudi authorities enable many guardians to catch them before they actually escape.[102] Bethany Vierra, a 31-year-old American woman, became the latest victim of the "male guardianship" system, as she was trapped in Saudi Arabia with her 4-year-old daughter, Zaina, despite having received a divorce from her Saudi husband.[103]

Some examples of that further highlight the ramifications of these restrictions include:

- In 2002, a fire at a girls' school in Mecca killed fifteen girls. Complaints were made that Saudi Arabia's "religious police," specifically the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, prevented them from leaving the burning building and hindered rescue workers because the students were not wearing modest clothing and, possibly, because they lacked male escorts.[104]

- In August 2005, a court in the northern part of Saudi Arabia ordered the divorce of Fatima Mansour, a 34-year-old mother of two, from her husband, even though they were happily married and her father (deceased) had approved the marriage. The divorce was initiated by her half-brother using his powers as her male guardian. He alleged that his half-sister's husband was from a tribe of a low status compared to the status of her tribe, and that the husband had failed to disclose this when he first asked for Fatima's hand. If sent back to her brother's home, Fatima feared domestic violence.[105][106] She spent four years in jail with her daughter before the Supreme Judicial Council overturned the decision.[107]

- In 2008, a wali married off his eight-year-old daughter to a 47-year-old man in order to have his debts forgiven.[108] The man's wife sought an annulment to the eight-year-old girl's marriage, but the Saudi judge refused to grant it.[109]

- In a 2009 case, a father vetoed several of his daughter's attempts to marry outside their tribe, and sent her to a mental institution as punishment.[110]

- In July 2013, doctors at King Fahd Hospital in Al Bahah postponed amputating a critically injured woman's hand because she had no male legal guardian to authorize the procedure. Her husband had died in the same car crash that injured her and her daughter.[96]

- In 2017, Manal al-Sharif reported meeting a woman in prison who had finished serving her criminal sentence, but because her male guardian refused to sign her release papers, she was being held indefinitely.[111]

Guardianship requirements are not written law, but instead are applied according to the customs and understanding of particular officials and institutions (hospitals, police stations, banks, etc.). When women initiate official transactions and grievances, the transactions are often abandoned because officers, or the women themselves, believe they need guardian authorization. Officials may demand the presence of a guardian if a woman cannot show an ID card, or if she is fully covered. These conditions make complaints against the guardians themselves extremely difficult.[70]

In 2008, Rowdha Yousef and other Saudi women launched a petition, "My Guardian Knows What's Best for Me," which gathered over 5,000 signatures. The petition defended the status quo and requested punishment for activists who demand "equality between men and women, [and] mingling between men and women in mixed environments."[74]

In 2016, Saudis filed the first petition to end male guardianship, signed by over 14,500 people. Women's rights supporter Aziza Al-Yousef delivered it in person to the Saudi royal court.[112]

Liberal activists reject guardianship and find it demeaning to women. They object to being treated like "subordinates" and "children".[76][79] They point to women whose guardians ended their careers, and those who lost their children because they lacked custody rights. The courts recognize obedience to the father as law, even in cases involving adult daughters.[113] Saudi activist Wajeha al-Huwaider agrees that most Saudi men are caring, but "it's the same kind of feeling they have for handicapped people or for animals. The kindness comes from pity, from lack of respect."[74] She compares male guardianship to slavery:[71]

The ownership of a woman is passed from one man to another. Ownership of the woman is passed from the father or the brother to another man, the husband. The woman is merely a piece of merchandise, which is passed over to someone else—her guardian. Ultimately, I think women are greatly feared. When I compare the Saudi man with other Arab men, I can say that the Saudi is the only man who could not compete with the woman. He could not compete, so what did he do with her? The woman has capabilities. When women study, they compete with the men for jobs. All jobs are open to men. 90% of them are open to men. You do not feel any competition. If you do not face competition from the Saudi woman, you have the entire scene for yourself. All positions and jobs are reserved for you. Therefore, you are a spoiled and self-indulged man.

The absurdity of the guardianship system, according to Huwaider, is shown by what would happen if she tried to remarry: "I would have to get the permission of my son."[79]

The Saudi government has approved international and domestic declarations regarding women's rights, and insists that there is no law of male guardianship. Officially, it maintains that international agreements are applied in the courts. International organizations and NGOs, on the other hand, are skeptical: "The Saudi government is saying one thing to the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva but doing another thing inside the Kingdom," said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East director at Human Rights Watch.[114] Saudi interlocutors told a UN investigator that international agreements carry little to no weight in Saudi courts.[70]

In 2017, when the Kingdom was elected to the UN women's rights commission, several human rights organizations disapproved of the decision. UN Watch director Hillel Neuer called the decision "absurd" and compared it to "making an arsonist into the town fire chief".[115] Swedish foreign minister Margot Wallström said that Saudi Arabia "ought to be [there] to learn something about women".[116]

In May 2017, the King passed an order allowing women to obtain government services such as education and health care without the permission of a guardian.[39]

In 2019, Saudi Arabia adopted new measures allowing women to travel abroad without needing permission.[117] In August 2019, a royal decree was published in the Saudi official gazette Umm al-Qura that would allow Saudi women over 21 to travel abroad without permission from a male guardian. Several other liberalizing measures were also included in the decree; however, it is unclear whether these measures have officially come into force.[118][119]

In April 2020, HRW reported that a number of Saudi women using pseudonyms on Twitter had stated demands for the abolition of the male guardianship system and sexual harassment. The rights organization quoted the women as stating that any attempt to flee abuse was not possible. Women fleeing abuse can still be arrested and forcibly returned to family members.[120]

On 16 August 2022, a female Saudi Arabian university student was sentenced to 34 years in prison for following and retweeting dissident and activists on Twitter.[121]

On 31 August 2022, a viral online footage from an orphanage in Khamis Mushait showed Saudi security forces, including some wearing civilian clothes, chasing and attacking women with tasers, belts, and sticks. The footage sparked a national and global outcry, prompting the Saudi Public Prosecution to open an investigation into the incident.[122] Research by the European Saudi Organisation for Human Rights has found that protests at similar facilities have led to harsh prison sentences for those involved.[123]

Absher app

[edit]The Saudi government's smartphone application Absher allows men to control whether women under their guardianship travel outside the kingdom. It also sends alerts to the man if a woman under his guardianship uses her passport at the border. In 2019, Absher came under global criticism. Many international communities and human rights organizations demanded its removal from Google and Apple web stores. Some critics include US Rep. Katherine Clark and Rep. Carolyn Maloney, who called the app a "patriarchal weapon".[124] US Senator Ron Wyden demanded the app's immediate removal. He called the Kingdom's control over women "abhorrent."[125] Apple and Google agreed to investigate the app.[126][127] However, following a thorough investigation, Google refused to remove the app from its web store, citing that the app does not violate the company's terms and conditions.[128] Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch accused Apple and Google of helping "enforce gender apartheid" by hosting the app.[129]

Some Saudi women say that the Absher app has made their lives easier as everything can be processed online, allowing, for instance, travel approval from a guardian in another city. Human rights critics see the app as a way of normalizing patriarchal control and tracking women's movements.[130]

Namus

[edit]Male guardianship is closely related to namus (or sharaf in a Bedouin context), roughly translated as "honor." It also carries connotations of modesty and respectability. The namus of a male includes the protection of the females in his family. He provides for them, and in turn, the women's honor (sometimes called ird) reflects on him. Namus is a common feature of many different patriarchal societies.

Since the namus of a male guardian is affected by that of the women under his care, he is expected to control their behavior. If their honor is lost, especially in the eyes of the community, he has lost control of them. Threats to chastity, in particular, are threats to the namus of the male guardian.[131] Namus can be associated with honor killing.[132]

In 2007, a young woman was murdered by her father for chatting with a man on Facebook. The case attracted widespread media attention. Conservatives called for the government to ban Facebook, on the basis that it incites lust and encourages gender mingling.[133]

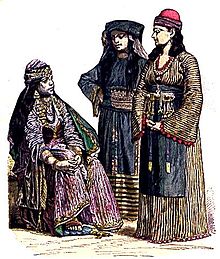

Hijab and dress code

[edit]

The hijab arises from the traditional Islamic norm whereby women are expected "to draw their outer garments around them (when they go out or are among men)" and dress in a modest manner.[134] Previously, the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, sometimes known as the religious police, has been known to patrol public places with volunteers focused on enforcing strict rules of hijab. With the 2016 reforms of Mohammed bin Salman,[135][136] the power of the CPVPV was drastically reduced, and it was banned "from pursuing, questioning, asking for identification, arresting and detaining anyone suspected of a crime."[137]

Among non-mahram men, women must cover the parts of the body that are considered intimate parts (awrah). In much of Islam, a woman's face is not considered awrah; however, in Saudi Arabia, and some other Arab states, all of the body is considered awrah except for the hands and eyes. Accordingly, most women are expected to wear the head-covering called the hijab, a full black cloak called an abaya, and a face-veil called niqab. Many historians and Islamic scholars hold that the custom, if not requirement, of the veil predates Islam in parts of the region. They argue that the Quran was interpreted to require the veil as part of adapting it to tribal traditions.[138]

The strictness of the dress code varies by region. In Jeddah, for example, many women go out with their faces and hair uncovered. Riyadh is more conservative by comparison. Some shops sell designer abayat that have elements such as flared sleeves or a tighter form. Fashionable abayat come in colors other than black and may be decorated with patterns and glitter. According to one designer, abayat are "no longer just abayas. Today, they reflect a woman's taste and personality."[79][139][140]

Although the dress code is often regarded in the West as a highly visible symbol of oppression, Saudi women place the dress code low on the list of priorities for reform, and some leave it off entirely.[141] Journalist Sabria Jawhar complains in The Huffington Post that Western readers of her blog are obsessed with her veil. She calls the niqab "trivial":[76][77]

[People] lose sight of the bigger issues like jobs and education. That's the issue of women's rights, not the meaningless things like passing legislation in France or Quebec to ban the burqa ... Non-Saudis presume to know what's best for Saudis, like Saudis should modernize and join the 21st century or that Saudi women need to be free of the veil and abaya ... And by freeing Saudi women, the West really means they want us to be just like them, running around in short skirts, nightclubbing and abandoning our religion and culture.

Some women say they want to wear a veil. They cite Islamic piety, pride in family traditions, and less sexual harassment from male colleagues. For many women, the dress code is a part of the right to modesty that Islam guarantees women. Some also perceive attempts at reform as anti-Islamic intrusion by Westerners. Faiza al-Obaidi, a Saudi biology professor, said: "They fear Islam, and we are the world's foremost Islamic nation."[91]

In 2002, multiple schoolgirls burned to death because religious policemen, who saw that they were not veiled, prohibited them from fleeing.

In 2014, a female anchor became the first to appear on Saudi state television without a headscarf.[142] She was reporting as a news anchor from London for the Al Ekhbariya channel.[142]

In 2017, a woman was arrested for appearing in a viral video dressed in a short skirt and halter top while walking around an ancient fort in Ushayqir. She was released following international outcry.[143] A few months earlier, a Saudi woman was detained for a short while after she appeared in public without a hijab. Although she did not wear a crop top or short skirt like the previous case, she was still arrested.[144]

As of late 2019, hijab and abaya are no longer required for women in public.[145][146][147]

Economic rights

[edit]Business and property

[edit]There are certain limitations on businesswomen in Saudi Arabia. Although now able to drive motor vehicles, a woman still cannot swear for herself in a court of law; a man has to swear for her. However, as part of the Saudi 2030 Vision, women have recently been encouraged to buy and own houses, either with partners or independently. This is part of Saudi Arabia's plan to increase Saudi ownership of houses to 70% by 2030.[148] According to a World Bank study titled "Women, Business and the Law 2020," which tracks how laws affect women in 190 economies, Saudi Arabia's economy scored 70.6 points out of 100, a dramatic increase from its previous score of 31.8 points. "2019 was a year of 'groundbreaking' reforms that allowed women greater economic opportunity in Saudi Arabia, according to the study's findings," said an Al Arabiya article on the report.[149]

Women's entrepreneurship on the rise

[edit]Vision 2030 is introducing women to new levels of leadership and economic empowerment. In Saudi Arabia, women entrepreneurs are now managing more small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The number of female entrepreneurs has increased more than 35% over the last decade in 2017.

Alhanoof Alzahrani, the co‑founder of Saudi Arabia's first crowdfunding company, "Scopeer," expressed her excitement and optimism about greater opportunities for Saudi women in business. She said: “Amid the economic diversification and push for women's empowerment, opportunities are everywhere. You just must be creative and willing to take risks.” Alhanoof added that the technology sector in Saudi Arabia will offer pockets of opportunity for local and foreign investors: “The country's push for digitalization is expected to generate demand for technology talents, as well as service providers in supporting technology development. We are more than happy to establish collaboration with Hong Kong, which is known to be a technology and innovation hub in Asia.”[150]

Several initiatives and programs have been launched in the country to promote and support entrepreneurship among young Saudi women. The General Authority of Small and Medium Enterprises (Monshaat), has introduced a loan guarantee program and regulation to reduce the administrative burden on SMEs. Workshops and training programs are also offered under the Badir Technology Incubators and Accelerators Program to promote an entrepreneurial culture among women university students.

Employment

[edit]According to the Saudi General Authority for Statistics, Saudi women constitute 33.2% of the native workforce as of 2020.[151] The rate of participation has grown from 14% in 1990 to 33.2% in 2020.[152] Between 2018 and 2020, the proportion of women in the native workforce increased from 20.2% to 33.2%.[153] In February 2019, a report was released indicating that 48% of Saudi nationals working in the retail sector were women.[154]

Some critics complain that women's skills are not being effectively used, since women make up 70% of students in Saudi institutes of higher education.[155] Some jobs taken by women in almost every other country are reserved for men in Saudi Arabia. For example, the Saudi delegation to the United Nations International Women's Year conference in Mexico City in 1975 and the Decade for Women conference in Nairobi in 1985 were made up entirely of men. Geraldine Brooks wrote, "Even jobs directly concerned with women's affairs were held by men."[156]

Historically, women's employment has been restricted under Saudi law and culture. In 2006, the Labor Minister Dr. Ghazi Al-Qusaibi said:

The [Labor] Ministry is not acting to [promote] women's employment since the best place for a woman to serve is in her own home ... therefore no woman will be employed without the explicit consent of her guardian. We will also make sure that the [woman's] job will not interfere with her work at home with her family, or with her eternal duty of raising her children ...[155]

Furthermore, women's work must also have been deemed suitable for the female physique and mentality. Women have been allowed to work only in capacities in which they can exclusively serve other women; there must have been no contact or interaction with the opposite gender.[157] A woman's work should not cause her to travel without a close male relative. This has presented considerable problems, as women were not allowed to drive motor vehicles until 2018, and little to no public transportation exists in the Kingdom. Before women were allowed to drive, most working women traveled to work without a male relative out of necessity.[97][98][99]

Consequently, until 2005, women only worked as doctors, nurses, teachers, women's bankers, and in a few other special roles in which they only had contact with women. Almost all of them had college and graduate degrees and were employed either in schools—where men were not permitted to teach girls—or in hospitals, because conservative families prefer that female doctors and nurses treat their wives, sisters, and daughters.[158] Positions of high public office such as judge were prohibited for women.[97][98][99]

Women's banks, which first opened in 1980, gave women places to put their money without having any contact with men. These banks employ women exclusively for every position, except for the guards posted at the door to see that no men enter by mistake. Author Geraldine Brooks again wrote, "Usually a guard was married to one of the women employees inside, so that if documents had to be delivered, he could deal with his wife rather than risking even the slight contact taking place between unmarried members of the opposite sex."[159] According to Mona al-Munajjed, a senior advisor with Booz & Company's Ideation Center, the number of Saudi women working in banking grew from 972 in 2000 to 3,700 in 2008.[160]

While the Labor Minister Al-Qusaibi stressed the need for women to stay at home, he also stated that "there is no option but to start [finding] jobs for the millions of women" in Saudi Arabia.[155] Previously, the Labor Ministry banned the employment of men or non-Saudi women in lingerie shops and other stores where women's garments and perfumes were sold.[clarification needed][161] This policy started in 2005 when the Ministry announced they would be staffing lingerie shops with women.[158] Since the shops served female customers, employing women would prevent the mixing of sexes in public (ikhtilat). Many Saudi women also disliked discussing the subject of their undergarments with male shop clerks.

This move was met with opposition from within the ministry and from conservative Saudis,[155] who argued the presence of women outside the home encouraged ikhtilat (mixing of sexes) and that, according to their interpretation of Sharia, a woman's work outside the house is against her fitrah (natural state). The few shops that employed women were "quickly closed by the religious police."[155][158] Women responded by boycotting lingerie shops, and in June 2011, King Abdullah issued another decree giving lingerie shops one year to replace male workers with women.[158] This was followed by similar decrees for shops and shop departments specializing in other products for women such as cosmetics, abayat and wedding dresses. The decrees came at "the height of the Arab Spring" and were "widely interpreted" by activists as an attempt to preempt "pro-democracy protests."[158] The policy has led to further clashes. Conservatives and religious police officers are on one side of the clash; the Ministry and female customers and employees of female-staffed stores are on the other. In 2013, the Ministry and the religious police leadership met to negotiate new terms. In November 2013, 200 religious police signed a letter stating that female employment was causing such a drastic increase in instances of ikhtilat that "their job was becoming impossible."[158]

When women find jobs that are also held by men, they often find it difficult to break into full-time work with employee benefits including allowances, health insurance and social security. According to a report in the Saudi Gazette, an employer told a female reporter that her health insurance coverage did not include care for childbirth, but a male employee was given such coverage for his wife.[162]

Saudi women are now developing professional careers as doctors, teachers and even business leaders, albeit in a process described in 2007 by ABC News as "painfully slow."[163] One such female professional is Dr. Selwa Al-Hazzaa, head of the ophthalmology department at King Faisal Specialist Hospital in Riyadh,[164] and in Lubna Olayan, named by Forbes and Time magazines as one of the Arab world's most influential businesswomen.[165]

Some "firsts" in Saudi women's employment occurred in 2013, when the Kingdom registered its first female trainee lawyer, Arwa al-Hujaili; its first female lawyer to be granted an official license from its Ministry of Justice, Bayan Mahmoud Al-Zahran; and the first female Saudi police officer, Ayat Bakhreeba.[166][167] Bakhreeba earned her master's degree in public law from the Dubai Police Academy, and is the first woman to obtain a degree from that academy.[168] Furthermore, her thesis on "children's rights in the Saudi system" was chosen as the best research paper by the police academy.[168] Additionally, in 2019, Yasmeen Al Maimani was the first Saudi woman to be a commercial pilot.[169]

A World Bank report found that, since 2017, Saudi Arabia has made "the biggest improvement globally" in issues of women's mobility, sexual harassment, retirement age and economic activity. The Kingdom fixed a woman's retirement age at 60, the same as men, thus stretching their earnings and contributions. According to Al Arabiya, "Amendments were adopted to protect women from discrimination in employment, to prohibit employers from dismissing a woman during her pregnancy and maternity leave, and to prohibit gender-based discrimination in accessing financial services."[149]

Current Saudi law ensures equal pay for women and men in both the private and public sectors.[170][171]

Military

[edit]Saudi Arabia opened non-combat military jobs to women in February 2018.[172] This followed a series of reforms enacted by Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman to advance the rights of women in Saudi Arabia.[173]

In January 2020, the chief of staff of the Saudi Arabian Armed Forces, General Fayyadh Al-Ruwaili, inaugurated the first women's military wing, allowing women to join combat military positions in all branches of the armed forces.[174][175]

Education

[edit]

In 2021, female literacy was estimated at 93%, not far behind that of men.[176] The 2021 data stands in stark contrast to that of 1970, when only 2% of women and 15% of men were literate.[177] More women receive secondary and tertiary education than men; 56% of all university graduates in Saudi Arabia were women as of 2019, and in 2008, 50% of working women had a college education, compared to 16% of working men.[178][179][180] As of 2019, Saudi women make up 34.4% of the native work force of Saudi Arabia.[181] The proportion of Saudi women graduating from universities is higher than in Western countries.[182]

One of Saudi Arabia's official educational policies is to promote "belief in the one God, Islam as the way of life, and Muhammad as God's Messenger." Official policy particularly emphasizes religion in the education of girls: "The purpose of educating a girl is to bring her up in a proper Islamic way so as to perform her duty in life, be an ideal and successful housewife and a good mother, ready to do things which suit her nature such as teaching, nursing and medical treatment." The policy also specifies "women's right[s] to obtain suitable education on equal footing with men in light of Islamic laws."[177]

Saudi women often specify education as the most important area for women's rights reform.[76][77][141]

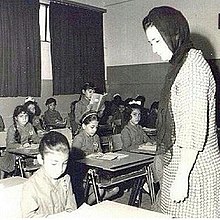

Elementary education

[edit]Public education in Saudi Arabia is sex-segregated at all levels, and in general, females and males do not attend the same school. Moreover, men are forbidden from teaching or working at girls' schools, and women were not allowed to teach at boys' schools until 2019.[183][184]

Higher education

[edit]Saudi Arabia is the home of Princess Nourah Bint Abdul Rahman University, the world's largest women-only university. Religious beliefs about gender roles and the perception that education is more relevant for men has resulted in fewer educational opportunities for women. The tradition of sex segregation in professional life is used to justify restricting women's fields of study. Traditionally, women have been excluded from fields such as engineering, pharmacy, architecture, and law.[184][185]

This has changed slightly in recent years; in 2021, nearly 60% of all Saudi university students were female.[186] Some fields, such as law and pharmacy, are beginning to open up for women. Though Saudi women can also study any subject they wish while abroad, the customs of male guardianship and purdah curtail this. In 1992, three times as many men studied abroad on government scholarships, although the ratio had been near 50% in the early 1980s.[177][187]

Women are encouraged to study to work in service industries, or to pursue fields in the social sciences. Education, medicine, public administration, natural sciences, social sciences, and Islamic studies are all deemed appropriate for women. Of all female university graduates in 2007, 93% had degrees in education or the social sciences.[184][185]

The King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, which opened in September 2009, is Saudi Arabia's first coeducational campus where men and women study alongside each other. Women attend classes with men, drive on campus, and are not required to veil themselves. In its inaugural year, 15% of the students were female, all of whom had studied at foreign universities. Classes are taught in English.[188]

The opening of the university sparked public debate. Sheikh Ahmed Qassim Al-Ghamdi, the controversial ex-chief of the Makkah region's mutaween, claimed that gender segregation has no basis in Sharia, or Islamic law, and that it has been incorrectly applied in the Saudi judicial system. Al-Ghamdi said that hadith, the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad, makes no references to gender segregation; he argues that therefore mixing is permitted under Sharia. After this statement, there were many calls for (and rumors of) his dismissal.[72][73]

Technology has played a central role in opening higher education to women. Many women's colleges use distance education to compensate for their generally poor access to transportation.[131] Male lecturers are not allowed to lecture at women's classes, and since there are few female lecturers, some universities use videoconferencing to allow male professors teach female students without face-to-face contact.[184]

Child marriage is another factor that hinders women's education. A child wife's responsibilities, such as housework and childbearing, are typically too burdensome for her to continue school. The dropout rate of girls increases around puberty, as they leave school upon marriage. Roughly 25% of college-aged young women do not attend college, and from 2005 to 2006, women had a 60% dropout rate.[clarification needed][185]

In 2009, the King appointed Norah al-Faiz as deputy minister for women's education; she was the first female cabinet-level official.[81]

In 2019, a new diploma in criminal law was made available to women.[189]

In July 2020, Saudi Minister of Education, Hamad bin Mohammed Al Al-Sheikh, appointed Lilac AlSafadi as president of the Saudi Electronic University. She is the first female president of a co-ed Saudi university.[190]

Sports

[edit]

Saudi Arabia was one of the few countries in the 2008 Olympics without a female delegation, although it does have female athletes.[191]

In June 2012, the Saudi Arabian Embassy in London announced that female athletes would compete in the Olympics in 2012 in London, England, for the first time.[192] Saudi blogger Eman al-Nafjan commented that as of 2012, Saudi girls are prevented from sports education at school, and that Saudi women have very little access to sports facilities. She also said that the two Saudi women who participated in the 2012 Olympics, runner Sarah Attar (who grew up in the United States) and judoka Wojdan Shaherkani, attracted both criticism and support on Twitter; and that Jasmine Alkhaldi, a Filipino swimmer born to a Saudi father, was widely supported by the online Saudi community.[193]

In 2013, the Saudi government sanctioned sports for girls in private schools for the first time.[194]

In their article "Saudi Arabia to let women into sports stadiums," Emanuella Grinberg and Jonny Hallam explain that conservative Saudis adhere to the strictest interpretation of Sunni Islam in the world. Under their guardianship system, women cannot travel or play sports without permission from male guardians. Some of these strict rules in Saudi Arabia have started to change. Mohammed bin Salman declared that by 2018, women would be allowed into sports stadiums. In September 2017, women were allowed to enter King Fahd Stadium for the first time for a celebration commemorating the Kingdom's 87th anniversary. They were seated in a specific section for families. Though welcomed by many, the move drew backlash from conservatives holding on to the country's strict gender segregation rules.[195]

When WWE began holding Saudi Arabia in 2018, the company initially announced that female wrestlers would not be allowed to participate.[196][197] On October 30, 2019, the promotion announced that Lacey Evans and Natalya would take part in the country's first professional wrestling match involving women at that year's edition of WWE Crown Jewel.[198] However, both wrestlers had to substitute their usual revealing attire for bodysuits that covered their arms and legs.[199]

In January 2020, Saudi Arabia hosted the Spanish Super Cup for the first time. The tournament hosted Barcelona, Valencia, Atlético Madrid and Real Madrid as the four participants. During the first match of the competition between Real Madrid and Valencia on January 8, Amnesty International workers gathered in front of the Saudi Embassy in Madrid and called for the release of Saudi women rights activist Loujain al-Hathloul and ten other activists. The rights group also informed the public that the match day marked Loujain's 600th day in detention.[200] In January 2020, Human Rights Watch, along with 12 other international human rights organizations, wrote a joint letter to the Amaury Sport Organisation ahead of the Saudi Dakar Rally. In their statement, the rights group urged ASO to use their decision to denounce the suppression of women's rights. The HRW's statement read, "The Amaury Sport Organisation and race drivers at the Dakar Rally should speak out about the Saudi government's mistreatment of women's rights activists for advocating for the right to drive."[201]

On September 29, 2020, Amnesty International raised concerns about the women's rights situation in Saudi Arabia, where a Ladies European Tour event was going to take place in November. The organization also urged those who were participating to show solidarity with the activists jailed in Saudi Arabia.[202]

Women's football in Saudi Arabia made great strides in 2022, with the women's national team competing in, and winning, their first international match by the score of 2–0 against Seychelles.[58] Later that year in December, Saudi Arabia made a bid to host the 2026 AFC Women's Asian Cup. Monika Staab, the manager of the Saudi Arabian women's national team, said: "This is an opportunity to bring the tournament to life, inspire a generation, and turbo-charge the continued growth of women's football."[203]

Mobility

[edit]In 2019, following suggestions made in 2017, Saudi women were given the ability to travel abroad freely without permission from male guardians.[204] As of August 2019, women over 21 can travel abroad without male permission.[205]

Many of the laws controlling women also apply to citizens of other countries who are relatives of Saudi men. For example, the following groups require a male guardian's permission to leave the country: foreign women married to Saudi men, adult foreign women who are the unmarried daughters of Saudi fathers, and foreign boys under the age of 21 with a Saudi father.[206]

In 2013, Saudi women were allowed to ride bicycles for the first time, although only in parks and other "recreational areas."[207] Female cyclists must be dressed in full body coverings and be accompanied by a male relative.[207] A 2012 film named Wadjda highlighted this issue.

Driving

[edit]Until June 2018, women were not allowed to drive in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia was the only country in the world at the time with such a restriction.[208] On 26 September 2017 King Salman decreed that women would be allowed to obtain driver's licenses in the Kingdom, which would effectively grant women the right to drive, within the next year.[209] Salman's decision was backed by a majority of the Council of Senior Religious Scholars. Salman's orders gave responsible departments 30 days to prepare reports for implementation, with the goal of removing the ban on women's driver's licenses by June 2018.[208] Newspaper editorials in support of the decree claimed that women were allowed to ride camels in the time of Muhammad.[210] The ban was lifted on 24 June 2018, and more than 120,000 women applied for driver's licenses that day.[211]

The UN Human Rights Office said, "The decision to allow women in Saudi Arabia to drive is a first major step towards women's autonomy and independence, but much remains to be done to deliver gender equality in the Kingdom."[212] Human rights expert Philip Alston and the UN Working Group on discrimination of women encouraged the Saudi regime to demonstrate further reform by repealing other discriminatory laws.[212]

Saudi Arabia technically had no written ban on women driving prior to 2018, but Saudi law requires citizens to use a locally issued licenses while in the country. Such licenses had not been issued to women, making it effectively illegal for women to drive.[213] Until 2017, most Saudi scholars and religious authorities declared women driving haram (forbidden).[214] Commonly given reasons for the prohibition on women driving included:[215]

- Driving a car may lead women to interact with non-mahram males; for example, in the event of traffic accidents.

- Driving would be the first step in an erosion of traditional values, for example gender segregation.

During the ban on female drivers, many women in rural areas still drove.[87] According to one Saudi native, rural women drove "because their families' survival depends on it," and because the mutaween "can't effectively patrol" remote areas. However, in 2010, mutaween were clamping down on this freedom.[216]

Critics of the ban argued that it violated gender segregation customs by needlessly forcing women to take taxis with male drivers, or ride with male chauffeurs. It also placed an inordinate financial burden on families, causing the average woman to spend half her income on taxis. Further, it impeded the education and employment of women, because students and workers generally need to commute. Male drivers have also been a frequent cause of complaints of sexual harassment. Finally, the public transport system is widely regarded as unreliable and dangerous.[217][218][219]

On 6 November 1990, 47 Saudi women who had valid licenses issued by other countries drove through the streets of Riyadh to protest the ban on Saudi women drivers.[220] The women were eventually surrounded by curious onlookers, then stopped by traffic police, who took them into custody. They were released after their male guardians signed statements that they would not drive again, but thousands of leaflets with their names and their husbands' names – with the words "whores" and "pimps" scrawled next to them – circulated around the city. These women were suspended from jobs, had their passports confiscated, and were told not to speak to the press. About a year after the protest, they returned to work and recovered their passports, but they were kept under surveillance and passed over for promotions.[221]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In 2008, women to drive advocates in Saudi Arabia collected about 1,000 signatures, hoping to persuade King Abdullah to lift the ban, but they were unsuccessful. He said that he thought women would drive when the society was ready for it:[87]

I believe strongly in the rights of women. My mother is a woman. My sister is a woman. My daughter is a woman. My wife is a woman. I believe the day will come when women will drive. In fact if you look at the areas of Saudi Arabia, the desert, and in the rural areas, you will find that women do drive. The issue will require patience. In time I believe that it will be possible. I believe that patience is a virtue.

On International Women's Day 2008, the Saudi feminist activist Wajeha al-Huwaider posted a YouTube video of herself driving in a rural area, where female drivers were tolerated, and requesting a universal right for women to drive. She commented: "I would like to congratulate every group of women that has been successful in gaining rights. And I hope that every woman that remains fighting for her rights receives them soon."[222][better source needed] Another women's driving campaign started during the 2011 Saudi Arabian protests when Al-Huwaider filmed Manal al-Sharif driving in Khobar and published the video on YouTube and Facebook.[223]

Many skeptics believed that allowing women the right to drive could lead to Western-style openness and an erosion of traditional values.[224]

In September 2011, a woman from Jeddah was sentenced to ten lashes by whip for driving a car.[225] In contrast to this punishment, Maha al-Qahtani, the first woman in Saudi Arabia to receive a traffic ticket, was only fined for the violation itself.[226] The whipping was the first time a woman was punished under the law for driving. Previously, when women were found driving they would normally be questioned and let go after they signed a pledge not to drive again.[227] The whipping sentence followed months of protests by female activists, and just two days after, King Abdullah announced greater political participation for women in the future.[226][225][228] King Abdullah overturned the woman's sentence.[229]

In 2014, another prominent activist, Loujain Al Hathloul, was arrested by Saudi police after crossing the UAE–Saudi border in her car. Although she had a valid UAE license, she was still detained.[230] After being badly treated and facing more than a year's delay in the start of her legal process, she, along with other women's rights activists, attended a hearing with the Saudi court on 12 February 2020. Al-Hathloul was also reportedly tortured by the prison authorities while in solitary confinement.[231][232] By May 15, 2020, al-Hathloul had been detained for two years. Her trial date was pushed back ‘indefinitely’ due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and her family has also been barred from seeing her amid the outbreak.[233]

In August 2020 al-Hathloul went on a hunger strike for six days, demanding that her parents be allowed to see her at the Al-Ha'ir prison. In October of that same year she started a second hunger strike, demanding the right to contact her family members.[234] She was released in February 2021. However, al-Hathloul is barred from leaving the country.[235][236][237]

Public and private transportation

[edit]Women have limited access to bus and train services. Where they have such access, they must use separate entrances and sit in back sections reserved for women.[184] In early 2010, the government considered a proposal to create a nationwide women-only bus system. Activists are divided on the proposal. Some say it will reduce sexual harassment and transportation expenses while helping to facilitate women entering the workforce. Others criticize it as an escape from the real issue of recognizing women's right to drive.[217][219]

The Dubai-based carsharing app service Careem started business in Saudi Arabia in 2013, and Uber arrived in 2014. Women account for 80% of their passengers. The Saudi government has also supported these initiatives as a means of reducing unemployment and, in its Saudi Vision 2030 initiative, has invested equity in both companies. Vehicle for Hire has improved mobility for women, and also promoted employment participation with its improved transport flexibility.[238]

To support working women, the Saudi government has launched the Wusool program, which provides transportation services to them.[239]

Legal issues

[edit]Political life

[edit]Saudi Arabia is an absolute monarchy with a Consultative Assembly (shura) of lawmakers appointed by the king. Prior to a September 2011 announcement by King Abdullah, only men 30 years of age and older could serve as lawmakers. As of 2011, women can be appointed to the Consultative Assembly.[34] Women first joined the Consultative Assembly in January 2013, occupying thirty seats.[240][241]

In 2013, three women were named as deputy chairpersons of three committees: Thoraya Obaid was named deputy chairwoman of the Human Rights and Petitions Committee, Zainab Abu Talib was named deputy chairwoman of the Information and Cultural Committee;,and Lubna Al-Ansari was named deputy chairwoman of the Health Affairs and Environment Committee.[240] Another major appointment occurred in April 2012, when Muneera bint Hamdan Al Osaimi was appointed assistant undersecretary in the medical services affairs department at the Ministry of Health.[242]

Women could neither vote nor run for office in the country's first municipal elections in 2005, or in the 2011 election cycle. They campaigned for the right to vote in the 2011 municipal elections, attempting unsuccessfully to register as voters.[243] In September 2011, King Abdullah announced that women would be allowed to vote and run for office in the 2015 municipal elections.[34][70][244][245] Although King Abdullah was no longer alive at the time of the 2015 municipal elections, women were allowed to vote and stand as candidates for the first time in the country's history.[246] Salma bint Hizab al-Oteibi was the first female elected official in the country.[247][248] According to unofficial results released to The Associated Press, a total of 20 female candidates were elected to the approximately 2,100 municipal council seats being contested, which made them the first women elected to municipal councils in the country's history.[249]

Women are allowed to hold position on boards of chambers of commerce. In 2008, two women were elected to the board of the Jeddah Chamber of Commerce and Industry. There are no women on the High Court or the Supreme Judicial Council. There is one woman in a cabinet-level position as deputy minister for women's education; she was appointed in February 2009.[81] In 2010, the government announced female lawyers would be allowed to represent women in family cases.[250] In 2013, Saudi Arabia registered its first female trainee lawyer, Arwa al-Hujaili.[166]

In court, the testimony of one man equals that of two women. In court proceedings, women generally must deputize male relatives to speak on their behalf.[251]

In February 2019, Princess Reema bint Bandar Al Saud was appointed as the Saudi ambassador to the US. She became the first female envoy in the history of the Kingdom.[252] As of 2021, there are three female diplomats who are serving as Saudi ambassadors.[253]

Identity cards

[edit]At age 15, male Saudis receive identity cards that they are required to carry at all times. Before the 21st century, women were not issued cards, but instead were named as dependents on their mahram's (usually their father's or husband's) ID card, so that, "strictly speaking," they were not allowed in public without their mahram.[254]

At the time, it was difficult for women to prove their identity in court. In addition to lacking ID cards, women could not own passports or driver's licenses. Instead, they had to produce two male relations to confirm their identity. If a man denied that the woman in court was his relative, "the man's word would normally be taken," wrote author Harvey North. This system made women vulnerable to false claims on their property and to violations of inheritance rights.[254]

The Ulema, Saudi's religious authorities, opposed the idea of issuing separate identity cards for women since non-mahrams would see women's faces. Many other conservative Saudi citizens argue that cards, which must show a woman's unveiled face, violate purdah and Saudi custom.[255] However, women were eventually issued ID cards.

In 2001, a small number of ID cards were issued for women who had the permission of their mahram.[256] By 2006, women no longer needed male permission to obtain an ID card, and by 2013, ID cards became compulsory for women.[257]

In 2008, women were allowed to enter hotels and furnished apartments without their mahram if they had their national identification cards.[258] In April 2010, a new, optional ID card for women was issued which allows them to travel in countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council. Women did not need male permission to apply for the card, but in 2010, they still needed male permission to travel abroad.[259] As of 2019, Saudi women over 21 no longer need male permission to travel.[205]

Family code

[edit]Marriage

[edit]In 2005, the country's religious authority officially banned the practice of forced marriage. Despite this, Saudi Arabia maintained that a marriage contract is officially between the husband-to-be and the father of the bride-to-be. As of 2005, the bride's consent is needed in a marriage. No Saudi citizen can marry a non-Saudi citizen without official permission.[260] In 2016, justice minister Walid al-Samaani announced that clerics who register marriage contracts would have to provide a copy to the bride "to ensure her awareness of her rights and the terms of the contract."[261]

Polygyny is legal in Saudi Arabia, though it is on the decline due to demographic and economic reasons.[262] Polyandry is forbidden.[263]

The Kingdom prevents Saudi women from marrying male expatriates who test positive for drugs (including alcohol), incurable STDs, or genetic diseases, but does not stop Saudi men from marrying female expatriates with such problems.[264]

Domestic violence

[edit]In 2004, a popular television presenter, Rania al-Baz, was severely beaten by her husband. Photographs of her "bruised and swollen face" were published in the press. Her case brought light to domestic violence in Saudi Arabia.[265][266] According to Al-Baz, her husband beat her after she answered the phone without his permission, and he said he intended to kill her.[267]

State data, published in 2012, estimated that between 16 and 50% of married Saudi women suffer intimate partner violence. Domestic violence against women and children was not seen as a crime in Saudi Arabia until 2013.[268] In 2008, the Prime Minister ordered that "social protection units," the Kingdom's version of women's shelters, be expanded. That year, the Prime Minister also ordered the government to draft a national strategy to deal with domestic violence.[269] Some Saudi royal foundations, such as the King Abdulaziz Center for National Dialogue and the King Khalid Foundation, have also led education and awareness efforts against domestic violence.[269] Five years later, Saudi Arabia launched its first major effort against domestic violence: the "No More Abuse" ad campaign.[269]

In August 2013, following a Twitter campaign, the Saudi cabinet approved a law that made domestic violence a criminal offense for the first time. The law calls for a punishment of up to a year in prison and a fine of up to 50,000 riyals (US$13,000), with doubled maximum punishments for repeat offenders.[268] The law criminalizes psychological and sexual abuse, as well as physical abuse. It also includes a provision obliging employees to report instances of abuse in the workplace to their employer.[270] Saudi women's rights activist Suad Abu Dayyeh welcomed the new laws, although she believed law enforcement would need training on domestic abuse. She also said that, given the tradition of male guardianship, the law would be difficult to enforce.[268]

Children

[edit]

In 2019, Saudi Arabia officially banned child marriages and set the minimum age for marriage as 18 years for both women and men.[271] In 2013, the average age at first marriage for Saudi women was 25.[272][273][274]

Senior clergy originally opposed the push to ban child marriage. They argued that a girl reaches adulthood at puberty. Most Saudi religious authorities have defended the marriage of girls as young as nine and boys as young as fifteen.[275] However, they also believe that a father can marry off his prepubescent daughter so long as consummation is delayed until puberty.[276] A 2009 think-tank report on women's education concluded "Early marriage (before 16 years)... negatively influences a woman's chance of employment and the economic status of the family. It also negatively affects her health as they are at greater risk of dying from causes related to pregnancy and childbirth."[185] A 2004 United Nations report found that 16% of Saudi female teens were or had been married.[260]

The government's Saudi Human Rights Commission condemned child marriage in 2009, calling it "a clear violation against children and their psychological, moral and physical rights." It recommended that marriage officials adhere to a minimum age of 17 for females and 18 for males.[185][277] A 2010 news report documented the case of Shareefa, an abandoned child-bride. Shareefa was married to an 80-year-old man when she was 10. The deal was arranged by the girl's father in exchange for money, and against the wishes of her mother. Her husband divorced her a few months after the marriage without her knowledge and abandoned her at the age of 21. The mother then attempted legal action, arguing that "Shareefa is now 21, she has lost more than 10 years of her life, her chance for an education, a decent marriage and normal life. Who is going to take responsibility for what she has gone through?"[278]

In 2013, the Directorate General of Passports allowed Saudi women married to foreigners to sponsor their children so that the children can have residency permits (iqamas) with their mothers named as the sponsors.[279] Iqamas also grant children the right to work in the private sector in Saudi Arabia while on the sponsorship of their mothers. They also allow mothers to bring their children living abroad back to Saudi Arabia if they have no criminal records. Foreign men married to Saudi women were also granted the right to work in the private sector while on the sponsorship of their wives on condition that the title on their iqamas should be written as "husband of a Saudi wife," and that they should have valid passports enabling them to return to their homes at any time.[280]

Parental authority

[edit]Legally, children belong to their father, who has sole guardianship. If a divorce takes place, women may be granted custody of their young children until they reach the age of seven (for girls) and nine (for boys), although sometimes women gain custody of older children. Older children are often awarded to the father or the paternal grandparents. Saudi women cannot confer citizenship to children born to a foreign father.[260]

Inheritance issues

[edit]The Quran states that daughters inherit half as much as sons.[Quran 4:11][281] In some rural areas, some women may not receive inheritance, as they are considered to be dependents of their fathers or husbands. Marrying outside the tribe is also grounds for limiting women's inheritance in rural areas.[260][282]

Sexual violence and trafficking

[edit]Under Sharia law, rape is punishable with any sentence from jail to execution. As there is no penal code in Saudi Arabia, there is no written law which specifically criminalizes rape or prescribes its punishment. The rape victim is often punished as well if she had first entered the rapist's company in violation of purdah. There is no prohibition against spousal or statutory rape. In April 2020, the Saudi Supreme Court abolished the flogging punishment from its court system, replacing it with jail time, fines, or both.[283]

Migrant women, often working as domestic helpers, represent a particularly vulnerable group. Their living conditions are sometimes slave-like; they may experience physical violence and rape. In 2006, U.S. ambassador John Miller, Director of the Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, said the forced labor of foreign female domestic workers was the most common kind of slavery in Saudi Arabia. Miller claimed human trafficking is a problem everywhere, but the number of foreign domestic workers in Saudi Arabia, coupled with loopholes in the system, cause many foreign workers to fall victim to abuse and torture.[284]

Women, like men, may be subject to harassment by the country's religious police, the mutaween, in some cases including arbitrary arrest and detention, and physical punishments.[285] A UN report cites a case in which two mutaween were charged with molesting a woman; the charges were dismissed on the grounds that mutaween are immune from prosecution.[70]

In some cases, victims of sexual assault are punished for khalwa, or being alone with an unrelated male, prior to the assault. In the 2006 Qatif rape case, an 18-year-old victim of kidnapping and gang rape was sentenced by a Saudi court to six months in prison and 90 lashes. The judge ruled she violated laws on segregation of the sexes, as she was in an unrelated man's car at the time of the attack. She was also punished for trying to influence the court through the media.[286] The Ministry of Justice defended the sentence, saying she committed adultery and "provoked the attack" because she was "indecently dressed."[287] Her attackers were found guilty of kidnapping and were sentenced for prison terms ranging from two to ten years along with up to a thousand lashes.[288]

According to Human Rights Watch, one of the rapists filmed the assault with his mobile phone, but the judges refused to allow it as evidence.[289][290] The victim told ABC News that her brother tried to kill her after the attack.[291] The case attracted international attention: the United Nations criticized social attitudes and the system of male guardianship, both of which deter women from reporting crimes. The UN report argued that women are prevented from escaping abusive environments because of their lack of legal and economic independence. They are further oppressed, according to the UN, by practices surrounding divorce and child custody, the absence of laws criminalizing violence against women, and inconsistencies in the application of laws and procedures.[292] The case prompted Egyptian-American journalist Mona Eltahawy to comment, "What kind of God would punish a woman for rape? That is a question that Muslims must ask of Saudi Arabia because unless we challenge the determinedly anti-women teachings of Islam in Saudi Arabia, that Kingdom will always get a free pass."[290] In December 2007, King Abdullah pardoned the victim, but he did not agree that the judge had erred.[70][287]

In 2009, the Saudi Gazette reported that a 23-year-old unmarried woman was sentenced to one year in prison and 100 lashes for adultery for taking a ride from a male stranger. She said she had been gang-raped, became pregnant, and tried unsuccessfully to abort the fetus. The flogging was postponed until after the delivery.[293]

Many Saudi women's rights activists were arrested during a crackdown on May 15, 2018, and have been subjected to sexual violence and torture in prison. Currently, 13 women's rights activists are on trial, and five of them are still in detention for defending women's rights.[294]

Progress and change

[edit]Changes in the enforcement of Islamic code have influenced women's rights in Saudi Arabia. The Iranian Revolution in 1979 and the September 11 attacks in 2001 against the United States had significant influence on Saudi cultural history and women's rights.

In 1979, the revolution in Iran led to a fundamentalist resurgence in many parts of the Islamic world. Fundamentalists tried to repel Westernization, and governments defended themselves against revolution. In Saudi Arabia, fundamentalists occupied the Grand Mosque (Masjid al-Haram) and demanded a more conservative state, including "an end of education of women."[295] The government responded with stricter interpretations and enforcement of Islamic laws. Newspapers were discouraged from publishing images of women, and the Interior Ministry discouraged women, including expatriates, from employment. Scholarships for women to study abroad were declined, and wearing the abaya in public became mandatory.[72][84][140][141]

In contrast, the September 11th, 2001 attacks against the United States precipitated a reaction against ultra-conservative Islamic sentiment; fifteen of the nineteen hijackers in the September 11 attacks came from Saudi Arabia. Since then, the mutaween have become less active, and reformists have been appointed to key government posts. The government says it has withdrawn support from schools deemed extremist and moderated school textbooks.[76][86][87]

The government under King Abdullah was regarded as moderately progressive. It opened the country's first co-educational university, appointed the first female cabinet member, and prohibited domestic violence. Gender segregation was relaxed but remained the norm. Critics described the reform as far too slow, and often more symbolic than substantive. Conservative clerics successfully rebuffed attempts to outlaw child marriage. Women were not allowed to vote in the country's first municipal elections, although Abdullah supported a woman's right to drive and vote. The few female government officials have had minimal power. Norah Al-Faiz, the first female cabinet member, could not be seen without her veil, appear on television, or talk to male colleagues except by videoconferencing. She opposes girls' school sports as premature.[86][87][88][296][297][298]

The government has made international commitments to women's rights. It ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, with the proviso that the convention could not override Islamic law. However, government officials told the United Nations that there is no contradiction with Islam, and the degree of compliance between government commitments and practice is disputed. A 2009 report by the UN questioned whether any international law ratified by the government has ever been applied inside Saudi Arabia.[70]

Dr. Maha Almuneef said, "There are small steps now. There are giant steps coming. But most Saudis have been taught the traditional ways. You can't just change the social order all at once."[86]

Local and international women's groups have pushed Saudi governments for reform, taking advantage of the fact that some rulers are eager to project a more progressive image to the West. The presence of powerful businesswomen in some of these groups helped to increase women's representation in Saudi Arabian government and society, although they are still rare.[86][286]