Satmar

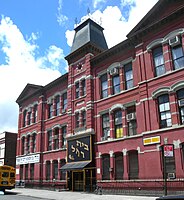

The main Satmar synagogue in Kiryas Joel, New York | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| around 26,000 households | |

| Founder | |

| Joel Teitelbaum | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States, Israel, United Kingdom, Canada, Romania, Australia, Argentina, Belgium, Austria | |

| Religions | |

| Hasidic Judaism | |

| Languages | |

| Yiddish |

Satmar (Yiddish: סאַטמאַר; Hebrew: סאטמר) is a group in Hasidic Judaism founded in 1905 by Grand Rebbe Joel Teitelbaum (1887–1979), in the city of Szatmárnémeti (also called Szatmár in the 1890s), Hungary (now Satu Mare in Romania). The group is a branch of the Sighet Hasidic dynasty. Following World War II, it was re-established in New York and has since grown to become one of the largest Hasidic dynasties in the world, comprising around 26,000 households.

Satmar is characterized by extreme conservatism, complete rejection of modern culture, and strong religious anti-Zionism. The community sponsors a comprehensive education and media network in Yiddish, which is also the primary language used by its members. Satmar also sponsors and leads the Central Rabbinical Congress, which serves as an umbrella organization for other highly conservative, anti-Zionist, and mostly Hungarian-descended ultra-Orthodox communities.

Following the death of Joel Teitelbaum in 1979, he was succeeded by his nephew, Moshe Teitelbaum. Since Moshe's death in 2006, the dynasty has been divided between his two sons, Aaron and Zalman Leib, each leading separate communities and institutions.

History

[edit]

Transylvania

[edit]Chananya Yom Tov Lipa Teitelbaum was the Grand Rebbe of the Sighet Hasidic dynasty. He died in 1904, and was succeeded by his oldest son, Chaim Tzvi Teitelbaum.

A few Sighet Hasidim preferred his second son, Joel, as their leader. Joel Teitelbaum left the town of Máramarossziget, and, on 8 September 1905, he settled in Szatmárnémeti (in Yiddish: Satmar). His Sighet supporters followed him, and he began to attract a following. Hungarian journalist Dezső Schön, who researched the Teitelbaum rabbis in the 1930s, wrote that Teitelbaum started referring to himself as the "Rebbe of Satmar" at that time.[1][2]

Teitelbaum's power base grew with the years. In 1911, he received his first rabbinical post as chief rabbi of Ilosva. In 1921, the northeastern regions of Hungary were ceded to Czechoslovakia and Romania, under the terms of the Treaty of Trianon. This area was densely populated with a segment of Orthodox Jewry known as Unterlander Jews. Many Sziget Hasidim, unable to regularly visit Chaim Tzvi's court, turned to Joel Teitelbaum instead.[3]

In 1925, Teitelbaum was appointed chief rabbi of Carei (Nagykároly). On 21 January 1926, Chaim Tzvi died unexpectedly, leaving his twelve-year-old son Yekusiel Yehuda to succeed him. Their mother emphasized Joel as successor, her grandson being too young for the position, and Joel returned to Sziget. However, Chaim Tzvi's followers would only accept Joel as a trustee-leader until Yekusiel became old enough. Although Teitelbaum was highly regarded, he was not well-liked there. Under these conditions, Teitelbaum would have become the dynasty's head in all but name,[4] which was nevertheless unacceptable for him and his mother, and they left Sziget again. In 1928, Teitelbaum was elected as chief rabbi of Szatmárnémeti itself. The appointment resulted in bitter strife within the Jewish community, and he only accepted the post in 1934.[1]: 320

Teitelbaum rose to become a prominent figure in Strictly-Orthodox circles, leading an uncompromisingly conservative line against modernization. Among other issues, he was a fierce opponent of Zionism and Agudath Israel.

The Jewish population of Hungary was spared wholesale destruction by the Holocaust until 1944. On 19 March 1944, the German Army occupied the country, and deportations to the concentration camps ensued. Teitelbaum sought to re-assure the frightened people who, for the most part, weren't able to leave Hungary, saying that by the merit of their religiosity, they would be saved. However, when the Germans invaded, he was saved by his devoted followers, who paid a huge ransom to have him included in the passenger list of the Kastner train. Teitelbaum reached Switzerland on the night of 7–8 December 1944, and soon immigrated to Mandatory Palestine. Many of Satmar's Jews were murdered by the Nazis.[5]

In America

[edit]A year after his daughter's death in Jerusalem,[6] Teitelbaum chose to move to the United States, arriving in New York aboard the MS Vulcania on 26 September 1946.[7]

Teitelbaum settled in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, along with a small group of followers, and set out to re-establish his sect, which had been destroyed in the Holocaust. His arrival in America allowed him to fully implement his views: The separation of religion and state enabled the Satmar dynasty, as well as numerous other Jewish groups, to establish independent communities, unlike the state-regulated structures in Central Europe.[8]: 30 In April 1948, his adherents founded "Congregation Yetev Lev", which was registered as a religious corporation.[2]: 47 Teitelbaum appointed Leopold Friedman (1904–1972), a former bank director, as the congregation's president, while he was declared supreme spiritual authority. After Friedman's death, he was replaced by Leopold (Leibish) Lefkowitz (1920–1998).[8] Teitelbaum's policy was to maintain complete independence by refusing to affiliate with, or receive financial aid from, any other Jewish group;[9] his Hasidim established a network of businesses that provided an economic base for the community's own social institutions.[8]: 32–34

The Satmar group grew rapidly, attracting many new followers. A 1961 survey established that its Williamsburg community included 4,500 people. From the 860 household heads, about 40 percent had been neither Satmar nor Sighet Hasidim in the pre-war years.[2]: 47, 262 In 1968, Satmar was already New York's largest Hasidic group, with 1,300 households in the city. In addition, there are many Satmar Hasidim in other parts of the United States, and worldwide.[10]

As part of his vision of complete isolation from the outside world, Teitelbaum encouraged his followers to make Yiddish their primary language, though many had previously used German or Hungarian, being immigrants from former Greater Hungary. The sect has its own Yiddish-oriented education system and several publishing houses which provide extensive reading material. Teitelbaum's work in this matter made him, according to Bruce Mitchell, the "most influential figure" in the maintenance of the language in the post-war period.[11] The uniformity of Satmar in America made it easier to teach young people the language, unlike in Europe: George Kranzler noted already in 1961 that the children speak Yiddish much better than their parents.[12]

On 23 February 1968, Teitelbaum suffered a stroke, which left him barely able to function. His second wife, Alte Feiga, administered the sect for the remainder of Teitelbaum's life, with the assistance of several Satmar functionaries.[10]: 85

In 1974, the sect began constructing the housing project Kiryas Joel in Monroe, New York, for its members. It was accorded an independent municipal status in 1977.[10]: 207 On August 19, 1979, Teitelbaum died of a heart attack.

Succession

[edit]

Teitelbaum was not survived by any children – all three of his daughters died in his lifetime. After prolonged vacillations by the community board, his nephew Moshe, Chaim Tzvi's second son, was appointed as successor, despite Alte Feiga's severe objections. Moshe Teitelbaum was proclaimed Rebbe on 8 August 1980, the first anniversary of his uncle's death by the Hebrew calendar.[10]: 126–128 The great majority of Hasidim accepted the new leader, though a small fraction called Bnei Yoel, which was unofficially led by Feiga, opposed him. The tense relations between both led to several violent incidents in the 1980s.[12]: 229

In 1984, Moshe Teitelbaum appointed his oldest son, Aaron, as chief rabbi of Kiryas Joel. Both incurred opposition from elements within the sect. They were blamed for exercising a centralized leadership style, and for lack of sufficient zealotry.[10]: 209–211

In 1994, the U.S. Supreme Court held, in the case of Board of Education of Kiryas Joel Village School District v. Grumet, that a school district whose boundaries had been drawn to include only Satmar children violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Until the late 1990s, Moshe Teitelbaum's heir apparent was his oldest son, Aaron. In 1999, his third son, Zalman, was recalled from his post as Satmar chief rabbi in Jerusalem and received the parallel post in the sect's largest enclave, Williamsburg. He was later proclaimed successor, and a struggle between the two brothers ensued. Aaron resided in Kiryas Joel, where he was considered the local authority, while Zalman held sway in Williamsburg.[13]

Schism

[edit]Following Moshe Teitelbaum's death in 2006, both groups of followers announced that their candidate was named successor in his will, and they were both declared Rebbes. Zalman and Aaron were engaged in prolonged judicial disputes as to who should control the Congregation's assets in Brooklyn. The sect has effectively split into two independent ones.

At the time of Moshe Teitelbaum's death, sources within the sect estimated it had 119,000 members worldwide, making it the world's largest Hasidic group.[14] A similar figure of 120,000 was cited by sociologist Samuel Heilman.[15] However, anthropologist Jacques Gutwirth estimated in 2004 that Satmar numbered about 50,000.[16] As of 2006, the dynasty controlled assets worth $1 billion in the United States.[14]

The two largest Satmar communities are in Williamsburg and Kiryas Joel. There are also significant Satmar communities in Borough Park, Brooklyn, and in Monsey and Bloomingburg, New York. Smaller concentrations can be found elsewhere. In North America, there are institutions in Los Angeles; Lakewood, New Jersey; and Montreal. Elsewhere, cities such as Antwerp, London, and Manchester; and in Argentina and Australia have Satmar groups, and there are many spread throughout Israel. Aaron Teitelbaum has stated that he wants to establish a community in Romania too.[17]

In addition to the Grand Rabbis' two main congregations, Chaim Yehoshua Halberstam, chief rabbi of the Satmar community in Monsey, became its local leader. Unlike the two brothers, Halberstam does not lay claim to the entire sect, though he conducts himself in the manner of a Hasidic Rebbe, accepting kvitel and holding tish. Another son, Lipa Teitelbaum, established his own congregation and calls himself Zenter Rav, in homage to the town of Senta, Serbia, where his father served as rabbi before World War II.

Guatemala Satmar Hasidim

[edit]There is a small community of Satmar gerim living in Guatemala, having rejected the Lev Tahor cult which initially converted the group before being expelled from the country.

The community of about 40 families has the full backing of the Satmar community in Williamsburg.[18]

Ideology

[edit]The principles of Satmar reflect Joel Teitelbaum's adherence to the Hungarian ultra-Orthodox school of thought, a particularly extreme variety,[19] founded by Hillel Lichtenstein and his son-in-law Akiva Yosef Schlesinger in the 1860s, on the eve of the Schism in Hungarian Jewry. Faced with rapid acculturation and a decline in religious observance, Lichtenstein preached utter rejection of modernity, widely applying the words of his teacher, Moses Sofer: "All that is new is forbidden by the Torah." Schlesinger accorded Yiddish and traditional Jewish garb a religious status, idealizing them as a means of separation from the outside world.

To reinforce his opposition to secular studies and the use of a vernacular, Schlesinger ventured outside the realm of strict halakha (Jewish law) and based his rulings on the non-legalistic Aggadah. The ultra-Orthodox believed that the main threat did not come from liberal Jewish Neologs, who advocated religious reform, but from the moderate traditionalists; they directed their attacks chiefly against the modern Orthodox Azriel Hildesheimer. Their power base lay among the Unterlander Jews of northeastern Hungary – roughly present-day eastern Slovakia, Zakarpattia Oblast, and Northern Transylvania – where modernity made little headway, and the local Galician-descended Jews were poor, unacculturated, and strongly influenced by Hasidism. Sighet, as well as most other Hungarian Hasidic dynasties, originated from these regions.[20]

Lichtenstein's successors were no less rigid; the leading authority of Hungarian extremists in the Interwar period, Chaim Elazar Spira of Mukačevo, regarded the Polish/German ultra-Orthodox Agudath Israel as a demonic force, as much as both the religious and secular streams of Zionism. He demanded complete political passivity, stating that any action to the contrary was akin to disbelief in divine providence. While Agudah opposed Zionism for seeing it as anti-religious, Spira viewed their plan for establishing an independent state before the arrival of the Messiah as "forcing the end", trying to bring Redemption before God prescribed it. In addition, he was an avowed anti-modernist: He sharply denounced Avraham Mordechai Alter, Rebbe of Ger, for introducing secular studies and allowing girls to attend school, and criticized modern medicine, believing the treatments recorded in the Talmud to be superior.[21] Though personal relations between Spira and Joel Teitelbaum were tense, his ideological stance had a strong influence over the younger rabbi. Aviezer Ravitzky believed it remained unacknowledged in the latter's writings due to the personal animosity between both.[22]

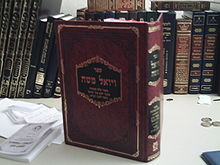

Already firmly anti-Agudist and anti-Zionist in the interwar period, Teitelbaum had to contend with the issues which baffled world Jewry in the aftermath of World War II: the Holocaust and the establishment of the State of Israel. In 1959, he enunciated his theological response in the book Vayoel Moshe (Hebrew: וַיּוֹאֶל מֹשֶׁה, romanized: va-yo'el moshe, lit. 'and Moses was content'; the title is from Exodus 2:21). The book contained three segments; the first was devoted to Teitelbaum's interpretation of an Aggadatic text from the Ketubot in the Talmud, the Midrash of the Three Oaths. It discusses the meaning of a phrase quoted three times in the Song of Songs (2:7, 3:5, 8:4): "I adjure you [...] that ye awaken not, nor stir up love until it please." The passage explains it as a reference to three oaths forced by God; two on the Children of Israel – that they "shall not go up" (migrate en masse) to their land before redemption, and neither rebel against the Gentile nations among which they are exiled – and the third upon all nations, "that they shall not oppress Israel too much".

Teitelbaum argued that the first two are binding and eternal, and that their intent was to keep the people in divinely decreed exile until they would all fully repent their sins and earn a solely miraculous salvation, without human interference. He sought to demonstrate that Rabbinic sages of the past all treated the Oaths as legally binding, and even those who did not mention them, like Maimonides, did so because this was common knowledge. His thesis was also meant to refute contrary pro-Zionist religious arguments, whether that the aggadic source of the Oaths made them non-binding, or that they were no longer valid, especially after the Gentiles "oppressed Israel too much" in the Holocaust. The Oaths were never utilized as a central argument beforehand, and his interpretation of the matter is Teitelbaum's most notable contribution to rabbinic literature. Based on his arguments, Teitelbaum stated that Zionism was a severe heresy and a rebellion against God, and that its pursuit brought about the Holocaust as a divine punishment; the continued existence of Israel was a major sin in itself, and would unavoidably lead to further retribution, as well as to the delaying of redemption. Vayoel Moshe crystallized the Rabbi's uncompromisingly hostile stance toward the state. The link between Zionism and the Holocaust became a hallmark of his religious worldview.[22]: 63–66 [19]: 168–180 [23]

Teitelbaum's rabbinic authority and wealthy supporters in the United States made him the leader of the radical, anti-Zionist flank of the ultra-Orthodox Jewish world. He adopted a policy of utter non-recognition towards the State of Israel, banning his adherents residing there from voting in the elections or from affiliating in any way with the state's institutions. When he visited the country in 1959, a separate train was organized for him, with no Israeli markings. The Israeli educational networks of Satmar and Edah HaChareidis, the latter also led by the Grand Rebbe, are fully independent and receive funding from abroad. Satmar and allied elements refuse to receive social benefits or any other monetary aid from the Israeli state and criticize those non-Zionist Haredim who do. Teitelbaum and his successors routinely condemned the Agudah and its supporters for taking part in Israeli politics. As to Religious Zionism, the Satmar Rebbe described its chief theologian, Abraham Isaac Kook, as "a wicked adversary and enemy of our Holy Faith".

In 1967, when the Western Wall and other holy places fell under Israel's control after the Six-Day War, Teitelbaum reinforced his views in the 1968 pamphlet Concerning Redeeming and Concerning Changing (Hebrew: עַל-הַגְּאֻלָּה וְעַל-הַתְּמוּרָה, romanized: a'l ha-ge'ulah v-a'l ha-tmurah; Ruth 4:7), arguing the war was no miracle, as opposed to statements by Menachem Mendel Schneerson of Chabad and others, whom he condemned severely, and forbade prayer at the Wall or at the other occupied holy sites, as he believed it would grant legitimacy to Israel's rule.[10]: 36–40 While providing some support for the otherwise unrelated Neturei Karta, Satmar has not always condoned its actions. Teitelbaum denounced them in 1967, when they co-operated with Arabs, and in 2006, the rabbinic court of Zalman Leib Teitelbaum's group placed an anathema upon those who visited the International Conference to Review the Global Vision of the Holocaust.[24] Satmar issued a further condemnation of Neturei Karta activities following the 2023 Hamas-led attack on Israel.[25]

Women's role

[edit]Satmar women are required to cover their necklines fully, and to wear long sleeves, long, conservative skirts, and full stockings. Whereas married Orthodox Jewish women do not show their hair in public, in Satmar, this is taken a step further: Satmar women shave their heads after their weddings, and wear a wig or other covering over their heads, while some cover the wig with a small hat or scarf.[26] The Grand Rebbe also insisted that the stockings of women and girls be fully opaque, a norm accepted by other Hungarian Hasidic groups which revered him.[8]: 30

Joel Teitelbaum opened Satmar's "Bais Ruchel" school network only because he feared that if he did not, many parents would send their daughters to Bais Yaakov.[12]: 57

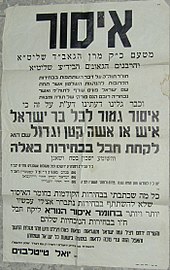

In 2016, the sect issued a decree warning that university education for women is "dangerous". Written in Yiddish, the decree warns:

It has lately become the new trend that girls and married women are pursuing degrees in special education [...] And so we'd like to let their parents know that it is against the Torah.[27]

Institutions

[edit]The sect operates numerous community foundations. Bikur Cholim ("Visiting the sick"), established in 1957 by Teitelbaum's wife Alte Feiga, concerns itself with helping hospitalized Jews, regardless of affiliation. Rav Tuv, founded in the 1950s to help Jews in the Soviet Union, aids Jewish refugees. Today, the organization mostly helps Jews from Iran and Yemen. Keren Hatzolah is a charitable fund to support yeshivas and the poor in Israel, providing for those who shun government benefits.

Teitelbaum founded a network of large educational institutions, both yeshivas and girls' schools. If its schools in New York were a public school system, it would be the fourth-largest system in the state, after those of New York City, Buffalo, and Rochester.[28] In most places, the girls' schools are called Beis Rochel, and the yeshivas Torah VeYirah. In 1953, Teitelbaum founded the Central Rabbinical Congress of the United States and Canada, which provides various services, including kashrut supervision.

Senior yeshivas include the United Talmudical Seminary and Yeshivas Maharit D'Satmar. [29] Satmar also operates its own rabbinical courts, which settle various issues within the community by the principles of Jewish Law.

The sect has a Yiddish newspaper called Der Yid, now privatized, and various other Yiddish publications. It is currently identified with Zalman's Hasidim; whereas Der Blatt, established in 2000, is owned and run by a follower of Aaron's.

-

Entrance of the Satmar Yeshiva in Brooklyn, New York

-

Beis Rochel, Brooklyn

In media

[edit]The Satmar community of Williamsburg was portrayed in the Netflix miniseries Unorthodox in 2020,[30] with consultation from Eli Rosen, a former Hasidic community member.[31] A majority of the show's dialogue is in Yiddish.

Notable people

[edit]

- Yossi Green (born 1955), American composer[32]

- Chaim Yehoshua Halberstam, Satmar rabbi in Monsey, New York

- Louis Kestenbaum (born 1952), American real estate developer[33]

- Meilech Kohn (born 1969), American singer[34]

- Aaron Teitelbaum (born 1947), rebbe of Satmar in Kiryas Yoel, New York

- Joel Teitelbaum (1887–1979), founding rebbe of Satmar

- Moshe Teitelbaum (1914–2006), rebbe

- Zalman Teitelbaum (born 1951), rebbe of Satmar in Williamsburg, Brooklyn

- Shmueli Ungar, singer

- Frieda Vizel (born 1985), American Youtuber

- Moshe Aryeh Freund, chief rabbi of the Edah HaChareidis

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Dezső Schön. Istenkeresők a Kárpátok alatt: a haszidizmus regénye. Múlt és Jövő Lapés Könyvk, 1997 (first edition in 1935). ISBN 9789638569776. pp. 286–287.

- ^ a b c Israel Rubin. Satmar: Two Generations of an Urban Island. P. Lang, 1997. ISBN 9780820407593. p. 42.

- ^ Yitsḥaḳ Yosef Kohen. Ḥakhme Ṭransilṿanyah, 490–704. Jerusalem Institute for the Legacy of Hungarian Jewry, 1988. OCLC 657948593. pp. 73–74.

- ^ Yehudah Shṿarts. Ḥasidut Ṭransilvanyah be-Yiśraʼel. Transylavanian Jewry Memorial Foundation, 1982. OCLC 559235849. p. 10.

- ^ Tamás Csíki. "Satu Mare". The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe.

- ^ David N. Myers. "'Commanded War': Three Chapters in the 'Military' History of Satmar Hasidism". Oxford University Press, 2013. pp. 25–26.

- ^ Retrieved on ancestry.com.

- ^ a b c d Jerome R Mintz. Hasidic People: A Place in the New World. Harvard University Press, 1992. ISBN 9780674041097. p. 31

- ^ George Kranzler. Hasidic Williamsburg: A Contemporary American Hasidic Community. Jason Aronson, 1995. ISBN 9781461734543. p. 112-113.

- ^ a b c d e f Jerome R. Mintz. Legends of the Hasidim. Jason Aronson, 1995. ISBN 9781568215303. p. 42.

- ^ Bruce Mitchell. Language Politics And Language Survival: Yiddish Among the Haredim in Post-War Britain. Peeters Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-9042917842. pp. 54–56.

- ^ a b c George Kranzler. Williamsburg: A Jewish Community in Transition. P. Feldheim (1961). OCLC 560689691. p. 208.

- ^ "Chasidic Split Colors Satmar Endorsement" (Archived 2006-05-10 at the Wayback Machine) from The Forward (07/27/2001).

- ^ a b Michael Powell. Succession Unclear After Grand Rebbe's Death. Washington Post, 26 April 2006.

- ^ Associated Press. "Moses Teitelbaum, 91; Rabbi Was Spiritual Leader of Orthodox Sect". Los Angeles Times, 25 April 2006.

- ^ Jacques Gutwirth. La renaissance du hassidisme: De 1945 à nos jours. Odile Jacob, 2004. ISBN 9782738114983. p. 69.

- ^ "Sighet – Marele rabin Aron Teitelbaum a venit special din Brooklyn, pentru a pune bazele unei băi rituale [VIDEO] - Salut Sighet".

- ^ Scarr, Cindy (2021-10-05). "Gut Shabbos, Guatemala - Mishpacha Magazine". Retrieved 2024-11-13.

- ^ a b Zvi Jonathan Kaplan. "Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum, Zionism, and Hungarian Ultra-Orthodoxy". Modern Judaism, Vol. 24, No. 2 (May 2004). p. 165. JSTOR 1396525.

- ^ Michael K. Silber. "The Emergence of Ultra-Orthodoxy: The Invention of Tradition". Originally published in: Jack Wertheimer, ed. The Uses of Tradition: Jewish Continuity Since Emancipation (New York-Jerusalem: JTS distributed by Harvard U. Press, 1992), pp. 23–84.

- ^ Allan L. Nadler. "The War on Modernity of R. Hayyim Elazar Shapira of Munkacz". Modern Judaism, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Oct. 1994), pp. 233–264. JSTOR 1396352.

- ^ a b Aviezer Ravitzky. Messianism, Zionism, and Jewish Religious Radicalism. University of Chicago Press (1996). ISBN 978-9651308505. p. 45.

- ^ Ketubot 111A.

- ^ Alan T. Levenson. The Wiley-Blackwell History of Jews and Judaism. John Wiley & Sons (2012). ISBN 9781118232934. p. 283.

- ^ "'Terrible desecration of God's name:' Satmar rebbe slams anti-Israel protesters". Jerusalem Post.

- ^ Goldberger, Frimet (November 7, 2013) "Ex-Hasidic Woman Marks Five Years Since She Shaved Her Head", Forward. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ Fenton, Siobhan; Rickman, Dina (August 22, 2016). "Ultra-Orthodox Jewish Sect Bans Women from Going to University in Case They Get 'Dangerous' Secular Knowledge". The Independent. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ Newman, Andy (April 25, 2006). "Rabbi Moses Teitelbaum Is Dead at 91". The New York Times.

- ^ "Yeshivas Maharit D'Satmar". yeshivasmaharit.org.

- ^ "The Making Of Unorthodox | Netflix". YouTube. 10 April 2020.

- ^ "Netflix's 'Unorthodox' went to remarkable lengths to get Hasidic Jewish customs right". Los Angeles Times. 2020-04-07. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ^ Winkler, Joseph (November 5, 2012). "Yossi Green Weathers Storm in Seagate". Tablet. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

Yossi Green—the Satmar-raised musician and composer profiled in today's Tablet—lives in the Seagate neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, along with many other prominent Jews.

- ^ Kusisto, Laura (June 16, 2014) "Familiar Face Emerges in LICH Saga", The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ Leibovitz, Liel (October 20, 2017). "Straight Outta Satmar: Hear the Biggest Hasidic Hit of Right Now". Tablet. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Feldman, Deborah (2012). Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-8701-2.

- Roberts, Sam, "Embracing a Race and Rejecting a Sect". Bookshelf. The New York Times, February 12, 2012.

- The New York Times "Bestseller: Non-fiction", October 21, 2012.

- Weisshaus, Yechezkel Yossef (2008). The Rebbe: A Glimpse into the Daily Life of the Satmar Rebbe Rabbeinu Yoel Teitelbaum. Translated by Mechon Lev Avos from Sefer Eidis B'Yosef by Rabbi Yechezkel Yosef Weisshaus. Machon Lev Avos. Lakewood, New Jersey: Distributed by Israel Book Shop. ISBN 978-1-60091-063-0.

External links

[edit]- "Satmar Dispute Over Many Millions To Be Decided by a Secular Court", New York Sun (March 22, 2006). Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- "One Rebbe or Two?", The Forward (05/05/06).

- Satmar Hasidic Williamsburg, newyorkerlife.com. Accessed December 18, 2022.

- "Hats On, Gloves Off" from New York magazine (05/08/06). Accessed December 18, 2022.