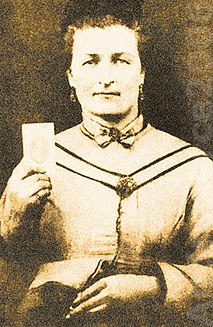

Malinda Blalock

Sarah Malinda Pritchard Blalock (March 10, 1839, or 1842 – March 9, 1901, or 1903) was a female soldier during the American Civil War. Despite originally being a sympathizer for the right of secession, she fought on both sides. She followed her husband, William Blalock, and joined the CSA's 26th North Carolina Regiment, disguising herself as a young man and calling herself Samuel Blalock. The couple eventually escaped by crossing Confederate lines and joining the Union partisans in the mountains of western North Carolina. During the last years of the war, she was a pro-Union marauder raiding the Appalachia region. Today she is one of the most remembered female combatants of the Civil War.

Early life and marriage

[edit]Malinda Pritchard was born March 10, 1839,[a] in Alexander County, North Carolina.[1]: 50 [b] Malinda was the daughter of John and Elizabeth Pritchard, and the sixth of nine children.[1]: 50 [2]: 14

When she was a child, Malinda Pritchard resided in Watauga County (also now Avery County) which was her main residence until her death. There, she attended a single-room schoolhouse.

She became a close friend of William McKesson Blalock, nicknamed "Keith" after a contemporary boxer, due to his skill at boxing.[2]: 11-12 Despite their families having been rivals for many years, she married William in 1861, aged 19.[1]: 50

Civil War

[edit]After the Civil War began, the western North Carolina communities in the Appalachian Mountains were divided over their political adherences. Neighbors and families argued with each other. Originally Malinda expressed her sympathy for the right of secession, but Keith and his stepfather Austin Coffey were ardent unionists, although Keith was opposed to President Lincoln, and they had planned to desert toward the Union someday. The Blalocks' opposing views did not affect their marriage.

When the Confederate 26th North Carolina Infantry, commanded by Colonel Zebulon Vance, showed up in the region to recruit, Keith began to plan an escape across the frontier from his local political enemies. He was hesitant about whether to flee directly toward Kentucky or enroll temporarily with the Confederate Army to desert across the enemy lines later.

Keith also considered the consequences of an untimely escape on Malinda, fearful that local distaste of his actions would cause her to be scapegoated in his absence. Spurred by the good pay in serving the "Greys", Keith trusted that he would receive a light military commission, possibly to northern Virginia for example, from where it would be easy to desert to the nearest "Yankee" regiment. He accompanied his neighbors to the recruitment office, signing up with the Confederate infantry.

Samuel Blalock

[edit]Fearing for Malinda, Keith had made sure that all local secessionists would see him leaving with the Confederates. However, when arriving at the enlistment gathering at the town's railroad depot, someone began to walk by his side, a mysterious recruit who was wearing a forage cap and had a particularly little physique and delicate features. Surprisingly, "He" turned out to be Malinda, his own wife.[1]: 51

Malinda was officially registered on March 20, 1862, at Lenoir, North Carolina, as "Samuel 'Sammy' Blalock", Keith's 20-year-old brother.[1]: 51 [3]: 132 This document and her discharge papers survive as one of the few existing records of a female soldier from North Carolina, from the many ones who may have actually served.

Confederate military life

[edit]Their plan to defect proved unworkable because, already before their arrival, the regiment had fought its biggest battle, which was the loss to the Union of the town of New Bern in eastern North Carolina. Instead of moving to Virginia's battlefront, they remained stationed far from the northern frontier at Kinston, North Carolina, on the Neuse River.

While maintaining her hidden identity, Malinda was a good soldier. One of their assistant surgeons, named Underwood, pointed out that "her disguise was never penetrated. She drilled and did the duties of a soldier as any other member of the Company, and was very adept at learning the manual and drill."[4]

Later Keith became a respected brevet sergeant, ordering Malinda then to "stay close to him". They fought in three battles together, but "Samuel"'s true identity remained still unknown.

The desertion

[edit]In April 1862, Keith's squad received the order to range the Neuse River's region by fording it during the night, to detect any enemy guarding-posts. Their ultimate objective was to track down the location of a particular Union regiment commanded by US General Ambrose Burnside.

At one point of the mission, a hard skirmish began. Most of Keith's squad retreated to safety, crossing back over the Neuse River. However, after regrouping, it was found that "Samuel" was missing. Keith promptly returned to the battlefield. He found Malinda clinging to a pine and bleeding profusely, with a bullet lodged in her left shoulder.[1]: 51-52

As quickly as he could, Keith carried Malinda back to the 26th's camp.[2]: 36 He brought her to the infirmary tent where she was attended by its surgeon, Dr. Thomas J. Boykin. The bullet was successfully removed, but the truth about "Samuel" was discovered during the medical examination.

After obtaining a promise from Boykin that he would spare them some time before reporting, Keith went to a nearby field of poison ivy. He stripped his clothes and flailed through the underbrush for about half an hour.

The next morning, he suffered a persistent fever while his affected skin was inflamed and covered by blisters. Keith told the doctors that he had a serious recurrent illness which was highly contagious, adding the ailment of a hernia also. Fearing an outbreak of smallpox, the doctors discharged Keith expeditiously from the regiment and confined him to his tent.

Malinda would remain stranded in the camp because her recent wound didn't yet merit a discharge. She decided to confront Colonel Vance once and for all. She offered herself as a volunteer to aid the sick Sergeant Keith on his return to Watauga. Vance's response was a clear "no", communicating to "Samuel" that instead "he" would be his new personal orderly.

At that point Malinda decided to tell Vance the truth. Vance's first reaction was of disbelief while calling the surgeon and commenting to him: "Oh Surgeon, have I a case for you!" However, the physician corroborated Malinda's statement. Immediately, Vance discharged "Samuel" and demanded the restitution of "his" original enlisting reward of 50 dollars.

Marauders

[edit]Malinda and her husband could return to Watauga then. Once there, though, Keith was soon required by the local Confederate forces, which demanded that he enlist again—after noting his healthy status—and return to the front. Otherwise, he would be judged by the new Confederate laws of military draft.

Therefore, Malinda and Keith fled again, toward Grandfather Mountain. There, they found more local deserters in the same condition. They stayed with them until the Confederate Army intercepted the group, injuring Keith in his arm.

Malinda and Keith moved then to Tennessee, where they joined the Union 10th Michigan Cavalry of Colonel George Washington Kirk, who was later succeeded by General George Stoneman. For some time, Keith accomplished some administrative chores as a recruitment agent.

However, the couple decided to enter in action again, this time for the Union, by joining Colonel Kirk's voluntary guerrilla squadrons, the 3rd North Carolina Mounted Infantry, on scouting and raiding missions throughout the Appalachia region of North Carolina.

With Malinda next to him, Keith began in Blowing Rock, North Carolina, as one of the leaders of the guides for the Watauga Underground Railroad. This was a way of escape from the Confederate jail at Salisbury, North Carolina, which was the largest facility of the state. Keith had to guide the escaped Union soldiers to safety in Tennessee. However, from 1863 on, the skirmishes against the patrolling enemy forces in the region were increasingly tougher.

Keith's pro-union guerrilla forces began to raid Watauga County. Because once they had been harshly humbled by the southern loyalists, the outlaws pitilessly raided their farms, stole and killed. Marauding throughout North Carolina's Appalachia region, they were soon feared by the entire state.

In 1863 Malinda realized she was pregnant, so she travelled to Tennessee to stay with another of the marauder's wives. Giving birth to a son on 8 April 1864, she spent some time with relatives in the area before leaving her young son with them and returning to military activities.[5]

Confederate vigilantes then murdered Keith's stepfather, Austin Coffey, and one of Austin's four brothers (William), while the other two survived the attack. The Coffeys had been betrayed by some local folks who were found and killed by Keith after the war.[6]

During the war, some of the most ill-fated actions of Malinda and Keith were their two pillaging incursions to the Moore family's farm in Caldwell County, late in 1863. One of Moore's sons, James Daniel, was the 26th's officer who recruited them originally. In the first incursion, Malinda was injured in her shoulder. During the second one, Moore's son was at home, recovering after the Battle of Gettysburg, while Keith got a shot in his eye and lost it.

During the war, Keith lost the use of a hand. He also murdered one of his uncles who had turned to the Confederacy.[clarification needed]

Later life

[edit]After the war, Malinda and Keith returned to Watauga, to live the rest of their lives as farmers, with their four children. For some time, they had troubles getting Keith's government pension. Afterward, they joined the Republican Party where, in 1870, Keith ran unsuccessfully for a place in the Congress of the United States.

Sarah Malinda Pritchard Blalock died in 1903 due to natural causes while she was sleeping.[1] She was buried in the Montezuma Cemetery of Avery County. Very affected, Keith moved to Hickory, North Carolina, taking his son Columbus with him.

On April 11, 1913, Keith died in a railroad accident. He lost control of his handcar on a curve, and was crushed to death.[1] Some versions attribute his death to a local payback for his past years with Malinda. He was buried beside her at Montezuma Cemetery. His stone badge reads: "Keith Blalock, Soldier, 26th N.C Inf., CSA."

See also

[edit]- List of female American Civil War soldiers

- List of wartime cross-dressers

- Deborah Sampson, impersonated a man to fight during the American War of Independence

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Eggleston, Larry G. (14 March 2003). "9. Sarah Malinda Pritchard Blalock: Woman Soldier and Guerrilla Raider". Women in the Civil War: Extraordinary Stories of Soldiers, Spies, Nurses, Doctors, Crusaders, and Others. McFarland & Company. pp. 50–54. ISBN 978-0786414932. LCCN 2003001313. OCLC 51580671. OL 3671828M. Retrieved 8 December 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d Stevens, Peter F. (2000). "1. A Young Giant". Rebels in Blue: The Story of Keith and Malinda Blalock. Taylor Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0878331666. LCCN 99056772. OCLC 42861670. OL 51365M. Retrieved 8 December 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Mays, Gwen Thomas (3 December 2007). "Blalock, Malinda [Sam Blalock] (ca. 1840-1901)". In Frank, Lisa Tendrich (ed.). Women in the American Civil War. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 132. ISBN 978-1851096008. LCCN 2007025822. OCLC 152580687. OL 11949332M. Retrieved 8 December 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Keith and Malinda Blaylock (Blaylock)". Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ Harper, Judith E. (2004). Women During the Civil War: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 36–40. ISBN 9780415937238 – via Google Books.

- ^ Baker Jr., Richard D. (2003). "Malinda Blaylock {Blalock}". Yahoo! GeoCities. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- "Troops: Female Soldiers". The Civil War Book of Lists: Over 300 Lists, from the Sublime ... to the Ridiculous. Combined Books. 1993. pp. 179–182. ISBN 978-0785817024. LCCN 92029823. OCLC 55804876. OL 8103528M. Retrieved 8 December 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Blanton, DeAnne, and Lauren M. Cook. They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8071-2806-6 OCLC 49415925

- Harper, Judith E. Women During the Civil War: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0-415-93723-X OCLC 51942662

- Simkins, Francis Butler and James Welch Patton. The Women of the Confederacy. Richmond: Garrett and Massie, Incorporated, 1936. ISBN 0-403-01212-0 OCLC 326632

External links

[edit]- Sarah Malinda Pritchard Blalock at Find a Grave

- "What part am I to act in this great drama?

- DeAnne Blanton – Women soldiers of the Civil War.

- K.G. Schneider – Women soldiers of the Civil War.

- Women in the Ranks: Concealed Identities in Civil War Era North Carolina. Archived 2014-06-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Keith and Malinda Blalock.