Suwon

Suwon

수원

| |

|---|---|

| Korean transcription(s) | |

| • Hangul | 수원시 |

| • Hanja | 水原市 |

| • Revised Romanization | Suwon-si |

| • McCune–Reischauer | Suwŏn-si |

From top, left to right: view of Suwon from Paldalsan Mountain, Samsung Digital City (Samsung Electronics HQ), Suwon World Cup Stadium, Hwaseong Fortress, Gwanggyo Lake Park, Suwon Station | |

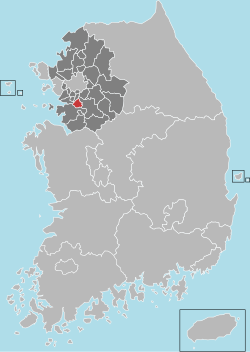

Location in South Korea | |

| Coordinates: 37°16′N 127°01′E / 37.267°N 127.017°E | |

| Country | |

| Area | Gyeonggi Province (Seoul Capital) |

| Administrative divisions | 4 gu, 43 dong |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Council |

| • Mayor | Lee Jae-jun (Democratic) |

| • Council | Suwon City Council |

| • Members of the Gyeonggi Provincial Council | List |

| • Members of the National Assembly | List |

| Area | |

• Total | 121.04 km2 (46.73 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 582 m (1,909 ft) |

| Population (september 2024[1]) | |

• Total | 1,195,045 |

| • Density | 9,900/km2 (26,000/sq mi) |

| • Dialect | Gyeonggi |

| Area code | +82-31-2xx |

| Flower | Azalea[2] |

| Tree | Pine[2] |

| Bird | Egret[2] |

| Website | Suwon City Council |

Suwon (Korean: 수원; Korean pronunciation: [su.wʌn]) is the largest city and capital of Gyeonggi Province, South Korea's most populous province. The city lies approximately 30 km (19 mi) south of the national capital, Seoul. With a population of 1.2 million,[4] Suwon has more inhabitants than Ulsan,[4][5] though it enjoys a lesser degree of self-governance as a 'special case city'.[6]

Traditionally known as the 'City of Filial Piety',[7] modern Suwon retains a variety of historical landmarks. As a walled city, it is a popular destination for day-trippers from Seoul,[8] with the wall itself—Hwaseong Fortress—receiving 1½ million visits in 2015.[9]

Suwon plays an important economic role as it is home to Samsung Electronics, Korea's largest and most profitable company.[10] The company's research and development centre is in Yeongtong District in eastern Suwon, where its headquarters have also been located since 2016.[11] Samsung's prominence in Suwon is clear: the company is partnered with Sungkyunkwan University,[12] which has a campus in the city; it also owns the professional football team Suwon Samsung Bluewings. This team has won the K League four times[13] and the Asian Super Cup twice.[14][15] The city is also home to the K League 1 team Suwon FC and the KBO League baseball team KT Wiz.

Suwon houses several well-known universities, most notably Sungkyunkwan University and Ajou University.[16] It is served by three expressways, the national railway network, and three lines on the Seoul Metropolitan Subway.

Name

[edit]Suwon means literally "water source".[17] The area has gone by different names since antiquity, but almost all of them have this meaning.[18][19] The name originally comes from the name of the statelet Mosuguk, from around the Proto–Three Kingdoms period.[18] Afterwards, the area and what is now Hwaseong were together called Maehol, Maetkol, or Mulgol (매홀; 맷골; 물골; 買忽).[20][18] In 757 CE, the name was changed to Susŏng-gun (수성군; 水城郡; lit. Susŏng County),[20][18] in order to disambiguate it from another territory with a similar-sounding name.[19] In 940, its name was changed to Su-ju (수주; 水州; lit. Su Province).[20][18] In the 11th century, it went by either Susŏng (different Hanja: 隋城) or Hannam (한남; 漢南; lit. south of Han).[18] In 1310, it received the name Suwon.[18]

In English, the name was formerly often spelt 'Sou-wen'.[21]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The area now corresponding to Suwon has been inhabited since at latest the early Bronze Age. Artifacts from that period to the early Iron Age have been found in the area, and include objects such as pottery, sculpture, and arrowheads.[18] One location these materials have been found is at Yeogisan, which is now a monument of Gyeonggi Province.[18]

During the Three Kingdoms of Korea period, the area was described as being of the territory of the statelet Mosuguk, part of the Mahan confederacy.[18][19] The area came under the influence of Goguryeo in the late 5th century CE, and then later became part of Unified Silla (668–935).[18][20]

It became part of Goryeo after a military campaign led by King Taejo.[18] In the 13th and 14th centuries, the area was promoted, demoted, merged, and made part of various administrative districts. The area then became a part of Joseon upon its founding, and in 1395 was made an administrative center of Gyeonggi Province.[18]

Until the late 18th century, Suwon's administrative centre was in modern-day Annyeong-dong at the foot of Hwasan (a hill in Hwasan-dong, Hwaseong).[22][18] In 1796, King Jeongjo relocated it to its current location at the foot of Paldalsan.[22][18] To protect this new city, he commanded the building of Hwaseong Fortress—a protective wall around the town.[23]

An 1899 administrative report had the population at 49,708 people in 12,579 households.[18]

Japanese colonial period

[edit]During the 1910–1945 Japanese colonial period, a number of prominent Korean independence activists came from or operated in Suwon. Kim Se-hwan and Yi Sŏn-gyŏng (이선경; 李善卿) were both arrested for their activities.[18]

Liberation to Korean War periods

[edit]On 15 August 1949, Suwon was promoted from a county to a city, with some of its former territory made into Hwaseong County.[18][24]

When the Korean War began, the United States Air Force 49th Fighter Wing, then stationed in Japan, was sent to Korea[25] with an initial mission of evacuating civilians from Suwon and Gimpo.[26] While on this mission, on 27 June 1950, US planes in Suwon were attacked by North Korean fighters. The ensuing Battle of Suwon Airfield became the first aerial combat of the war.[27] Suwon Airfield was attacked again two days later while General Douglas MacArthur was on site.[28] Though the US repelled both attacks, Suwon fell to the advancing North Koreans one week later, on 4 July 1950.[29] The following day saw the first land conflict between United States and North Korean forces, the Battle of Osan.

North Korean troops were not the only threat to life: in the early days of the war, southern authorities feared left-leaning civilians, and many were killed.[30] Suwon was a site of such killings: eyewitness account from US intelligence officer Donald Nichols places Suwon as the location of a massacre of approximately 1,800 in late June 1950.[31][32][33]

Suwon was retaken, fell again to the North, before being recaptured for the final time. In total, the city changed hands four times during the war.[34]

While under southern authority, Suwon hosted forces from several countries. For example, on 16 December 1950, the Greek Expeditionary Force relocated from Busan to Suwon, attached to the US 1st Cavalry Division.[35] The city also appeared strategically important, as in late 1951, the US Air Force's top fighter pilot Gabby Gabreski was placed in charge of Suwon Air Base.[26][36]

A memorial to French forces was erected in 1974 near the Yeongdong Expressway's North Suwon exit.[37] This was renovated in 2013.[38]

Recent history

[edit]In 1964, the headquarters of Gyeonggi Province began a process of relocation from Seoul to Suwon.[39][18] Seoul had left the province in 1949.[40] When the construction of the headquarters was completed on 23 June 1967, the date was set as a new annual holiday: Suwon Citizen's Day (수원시민의 날). The Hwahong Cultural Festival (now Hwaseong Cultural Festival) was established to celebrate the occasion.[18]

Suwon has experienced a number of administrative territory changes since the 1960s. In 1963, Suwon expanded greatly as 20 villages were incorporated from Hwaseong-gun.[41] In 1983, two more villages were acquired from Yongin.[42][18] In 1987, Suwon expanded westwards, acquiring another two villages from Hwaseong.[43][44][18] Gwonseon District and Paldal District were established in 1988.[18] It received more territory from Hwaseong and Yongin in 1994,[45][18] and again from Hwaseong in 1995.[18] It established Yeongtong District in 2003.[18]

In preparation for the construction of a new planned city Gwanggyo, there were two-way exchanges of land between Suwon and Yongin in 2007[46][47] and 2019.[48][49] Suwon's most recent land exchange occurred in 2020, when it swapped some land parcels with Hwaseong.[50]

Geography

[edit]Suwon lies in the north of the Gyeonggi plain, 30 km (19 mi) south of the national capital, Seoul. It is bordered by the cities of Uiwang to the north-west, Yongin to the east, Hwaseong to the south-west, and Ansan to the west.[51] Suwon is near the Yellow Sea coast: at its closest point, on the 239-metre (784 ft) Chilbosan ridge to the west, Suwon lies 18.2 km (11.3 mi) from Ueumdo[52] in Sihwa Lake, a coastal inlet cordoned off to drive the world's largest tidal power station.[53]

Geology and topography

[edit]Suwon is primarily composed of Precambrian metamorphic rock. It has amphibolites that intrude through these, and also granites from the Mesozoic Era.[54]

Most of Suwon is composed of biotite granite (Jbgr) from the Jurassic period. This granite is centred on Paldalsan. A form of Daebo granite, this rock is distributed through Homaesil-dong, Geumgok-dong, Dangsu-dong, Seryu-dong, Seodun-dong, Gwonseon-dong, and other areas. Its main constituent minerals are quartz, plagioclase, orthotic, biotite, and amphibole.[54]

Precambrian biotite gneiss (PCEbgn) is found in northern Suwon, specifically Pajang-dong, Gwanggyo-dong, Woncheon-dong, and Maetan-dong. Visible rocks here are composed of quartz, feldspar, biotite, amphibole, and muscovite; and are generally dark grey or dark green. Mesozoic biotite granite intrudes through these.[54]

Precambrian quartzo-feldspathic gneiss (PCEqgn) is distributed in some mountainous areas in Hagwanggyo-dong and Sanggwanggyo-dong in northern Suwon. This gneiss has primarily undergone silicification, and is mainly composed of quartz, feldspar, biotite, and muscovite. It is grey, grey-brown, and white.[54]

Suwon's single tectonic fault splits from the Singal Fault in Iui-dong, creating the Woncheonri Stream. The stream follows the fault through Ha-dong, Woncheon-dong, and Maetan-dong till it joins the Hwangguji Stream in Annyeong-dong, Hwaseong. This is a 20 km-long vertical fault running SSW, eventually to the Yellow Sea. In Suwon, biotite gneiss and biotite granite are brought into contact by the fault.[54]

While the low-lying fault sits in the south of Suwon, the north is hillier: the city's highest point is Gwanggyosan (582 m (1,909 ft)) on the border with Yongin.[55]

Streams and lakes

[edit]Most of Suwon's streams originate on Gwanggyosan or other nearby peaks. Since the city is bounded to the north by Gwanggyosan, to the west by Chilbosan, and to the east by other hills, the streams, chiefly the Hwanggujicheon, Suwoncheon, Seohocheon, and Woncheollicheon, flow southwards.[56] After merging, they eventually empty into the Yellow Sea at Asan Bay. The entirety of Suwon is drained in this manner.[57]

Several of Suwon's streams feature lakes. Since there are few natural lakes on the Korean mainland,[58] Suwon's lakes are in fact small reservoirs. These 11 reservoirs are Chungmanje, otherwise known as Seoho (서호) near Hwaseo Station;[59] Irwol Reservoir (일원 저수지) near Sungkyunkwan University; Bambat Reservoir (밤밭 저수지) near Sungkyunkwan University Station;[60] Manseokkeo, otherwise known as Irwang Reservoir (일왕 저수지) in Manseok Park;[61] Pajang Reservoir (파장 저수지) near the North Suwon exit of the Yeongdong Expressway; Gwanggyo Reservoir (광교 저수지) and Hagwanggyo Reservoir (하광교 소류지) at the foot of Gwanggyosan; Woncheon and Sindae Reservoirs (원천 저수지, 신대 저수지) in Gwanggyo Lake Park; and Geumgok Reservoir (금곡 저수지), a small lake at the foot of Chilbosan. Irwang Reservoir (Manseokkeo) has been designated a world heritage site for irrigation.[62] Wangsong Reservoir (왕송 저수지), on the border with Uiwang, used to be partly in Suwon, but after controversial boundary changes, it is now entirely in Uiwang.[63]

Climate

[edit]Suwon has both a humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfa), and a humid subtropical climate (Köppen: Cwa).[64]

The city is prone to occasional flooding: the 1998 flood caused the death of a US soldier,[65] and 145 mm (5.7 in) of rain fell in 24 hours in 2010.[66]

| Climate data for Suwon (1991–2020 normals, 1964–2023 extremes) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.3 (59.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

25.0 (77.0) |

30.5 (86.9) |

33.2 (91.8) |

34.0 (93.2) |

37.5 (99.5) |

39.3 (102.7) |

34.0 (93.2) |

29.0 (84.2) |

25.8 (78.4) |

17.8 (64.0) |

39.3 (102.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 2.8 (37.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

11.3 (52.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

23.6 (74.5) |

27.5 (81.5) |

29.3 (84.7) |

30.3 (86.5) |

26.4 (79.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

12.5 (54.5) |

4.9 (40.8) |

17.7 (63.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.1 (28.2) |

0.3 (32.5) |

5.7 (42.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

17.6 (63.7) |

22.2 (72.0) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

7.2 (45.0) |

0.1 (32.2) |

12.5 (54.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −6.6 (20.1) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

0.6 (33.1) |

6.4 (43.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

17.9 (64.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

17.1 (62.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −24.8 (−12.6) |

−25.8 (−14.4) |

−11.3 (11.7) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

2.3 (36.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

13.0 (55.4) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

−24.4 (−11.9) |

−25.8 (−14.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 18.1 (0.71) |

28.3 (1.11) |

40.7 (1.60) |

71.6 (2.82) |

95.0 (3.74) |

122.9 (4.84) |

385.1 (15.16) |

296.3 (11.67) |

133.5 (5.26) |

54.1 (2.13) |

48.9 (1.93) |

25.8 (1.02) |

1,320.3 (51.98) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 6.7 | 6.2 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 8.6 | 9.6 | 15.4 | 14.0 | 8.6 | 6.1 | 9.0 | 8.3 | 107.5 |

| Average snowy days | 6.9 | 5.3 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 6.8 | 23.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 63.0 | 61.9 | 62.2 | 62.1 | 66.1 | 71.4 | 79.9 | 77.6 | 73.2 | 69.8 | 67.9 | 64.4 | 68.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 174.3 | 178.7 | 205.7 | 214.5 | 229.7 | 195.0 | 138.2 | 168.7 | 184.6 | 208.9 | 162.5 | 166.2 | 2,227 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 54.0 | 56.2 | 53.4 | 54.6 | 50.4 | 42.8 | 30.5 | 39.5 | 48.8 | 57.4 | 51.6 | 53.4 | 48.6 |

| Source: Korea Meteorological Administration (percent sunshine 1981–2010)[67][68][69] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

[edit]

The city is composed of four gu (districts).[16] Jangan District (장안구) and Gwonseon District (권선구) were established on 1 July 1988. On 1 February 1993, parts of Jangan District and Gwonseon District became a new district, Paldal District (팔달구). The newest district is Yeongtong District (영통구), which separated from Paldal District on 24 November 2003. These districts are in turn divided into 42 dong.[70]

Suwon has several new 'towns', e.g., Homaesil[71] and Gwanggyo. The latter is perhaps the most notable of these: the first stage of its construction was completed in 2011.[72]

Demography

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 167,201 | — |

| 1980 | 310,476 | +85.7% |

| 1990 | 661,396 | +113.0% |

| 2000 | 946,704 | +43.1% |

| 2010 | 1,071,913 | +13.2% |

| 2020 | 1,210,150 | +12.9% |

| Source: [73] | ||

Suwon is 50.3% male (49.7% female), and 2.9% foreign. On average, there are 2.3 residents per household. Further details for each district are shown below (figures from 31 December 2023).[4]

| Total people | Korean males | Korean females | Korean (total) | Foreign males | Foreign females | Foreign (total) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suwon (total) | 1,233,424[4] | 602,346 | 594,911 | 1,197,257 | 17,837 | 18,330 | 36,167 |

| Gwonseon District | 375,574 | 184,970 | 181,197 | 366,167 | 4,558 | 4,849 | 9,407 |

| Jangan District | 277,645 | 136,145 | 134,704 | 270,849 | 3,312 | 3,484 | 6,796 |

| Paldal District | 208,791 | 99,290 | 97,923 | 197,213 | 5,917 | 5,661 | 11,578 |

| Yeongtong District | 371,414 | 181,941 | 181,017 | 363,028 | 4,050 | 4,336 | 8,386 |

Religion

[edit]The Catholic Diocese of Suwon was created in 1963 by Pope Paul VI.[74][75] The cathedral—St Joseph's—is at 39 Imok-ro, Jeongja-dong.

Suwon is the birthplace of the former president of the Baptist World Alliance, Kim Janghwan (Billy Kim).[76] Mr founded the Suwon Central Baptist Church,[77] though this is located in Yongin.

Mireukdang (미륵당), a small shrine to Maitreya, is located in Pajang-dong. This has a religious basis fusing Buddhism and traditional local religions.[78][79]

Crime

[edit]Illegal dumping of household waste has been a problem in Suwon, and the city council has addressed this by increasing urban greenery. This approach appears to have reduced the scale of the problem.[80]

| Category | Crime | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Property crime | Theft | 4,202 |

| Possession of stolen property | 8 | |

| Fraud | 6,183 | |

| Embezzlement | 1,277 | |

| Breach of trust | 70 | |

| Destruction | 1,510 | |

| Violent crime (serious) | Murder | 16 |

| Robbery | 7 | |

| Arson | 28 | |

| Sexual assault | 934 | |

| Violent crime (lesser) | Violence | 2,988 |

| Injury | 429 | |

| Intimidation | 540 | |

| Extortion | 159 | |

| Kidnapping, abduction | 4 | |

| False arrest, confinement | 33 | |

| Violation of The Punishment of Violence, Etc. Act (e.g., burglary) | 29 | |

| Violation of The Punishment of Violences, Etc. Act (e g., Formation of illegal organizations, and such activities) | 0 | |

| Forgery | Currency | 7 |

| Valuable securities, revenue stamp, postage | 2 | |

| Documents | 228 | |

| Seal | 11 | |

| Public official crime | Abandonment of duties | 18 |

| Abuse of authority | 30 | |

| Receiving bribes | 2 | |

| Giving bribes | 0 | |

| Crime against morality | Gambling, lotteries | 1,342 |

| Deceased person | 1 | |

| Other obscene acts | 79 | |

| Negligence | Inflicting bodily injury or death through negligence | 52 |

| Inflicting bodily injury or death through occupational negligence | 47 | |

| Fire caused by negligence | 57 | |

| Misc. | Defamation | 759 |

| Obstruction of rights | 134 | |

| Credit business, auction | 438 | |

| Trespass | 439 | |

| Violation of secrecy | 4 | |

| Abandonment | 5 | |

| Traffic obstruction | 10 | |

| Obstruction of official duties | 186 | |

| Escape, harbouring criminals | 4 | |

| Perjury, destruction, and concealment of evidence | 83 | |

| False accusation | 108 | |

| Breach of the peace | 4 | |

| Insurrection | 0 | |

| Drinking water crimes | 0 | |

| Water use crimes | 0 |

Education

[edit]

There are several universities and colleges in Suwon. These include Sungkyunkwan University's Natural Sciences Campus, Kyonggi University, Ajou University, Dongnam Health University, Gukje Cyber University, Hapdong Theological Seminary, and Suwon Women's University. Despite their names, the University of Suwon and Suwon Science College are not actually in Suwon, but in neighbouring Hwaseong. Seoul National University's agriculture campus was located in Suwon until 2005; it is now in Seoul.[82]

Suwon has 44 high schools, 57 middle schools, 100 primary schools, and 180 kindergartens.[83] Three schools are dedicated to special education: Jahye School (47 Subong-ro, Tap-dong),[84] Suwon Seokwang School (517 Jangan-ro, Imok-dong),[85] and Areum School (32 Gwanggyo-ro, Iui-dong).[86] Special education is also provided in some regular schools, e.g., Suwonbuk Middle School (37 Gwanggyosan-ro, Yeonghwa-dong).[87] There is also a centre for lifelong learning at Kyemyung High School (88 Jangan-ro 496 beon-gil, Imok-dong),[88] and there are two international schools in the city: Gyeonggi Suwon International School[89] and Suwon Chinese International School (수원화교중정소학교; 水原華僑中正小學)[90]

| Gwonseon District | Jangan District | Paldal District | Yeongtong District | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kindergarten | Public (dedicated k'gtn) | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 11 |

| Public (in elem. sch.) | 32 | 19 | 11 | 23 | 85 | |

| Private | 29 | 21 | 10 | 24 | 84 | |

| Elementary school | Public | 33 | 22 | 15 | 28 | 98 |

| Private | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Middle School | Public | 13 | 13 | 5 | 20 | 51 |

| Private | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 6 | |

| High School | Public | 7 | 9 | 3 | 12 | 31 |

| Private | 2 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 13 |

Environment

[edit]Throughout South Korea, water management is a challenge.[91] Suwon is 11% self-sufficient in its use of water, and plans to increase this to 50% through rainwater harvesting, including building retention facilities; and by treating and reusing sewage.[92]

Air pollution in Suwon appears to be from a range of industrial and other sources, with origins of coarse particulate matter (PM10) shown in the pie chart.[93]

PM10 sources on the Suwon–Yongin border:

Industry

[edit]The largest employer in Suwon is Samsung Electronics, which was founded in the city in 1969.[94] Its headquarters remain in Suwon, located today with the company's large R&D complex in Maetan-dong. Samsung's presence in the city can be seen through its sponsorship of local sports teams such as Suwon Samsung Bluewings Football Club[95] and two of the oldest domestic basketball teams—Samsung Thunders and Samsung Life Blueminx—both of which have since left Suwon.[96][97][98][99] Other major companies in Suwon include SK Chemical,[100] Samsung SDI,[101] and Samsung Electro-Mechanics.[102]

- Samsung Electronics On September 1, 1973, Samsung Electronics moved its headquarters from Euljiro, Seoul to Suwon. This was to establish an electronic components facility process with Japan's SANYO Electric Co., Ltd. As a result, the status of Suwon City grew along with the growth of Samsung Electronics.

Landmarks

[edit]Hwaseong Fortress

[edit]Hwaseong Fortress, built under the orders of King Jeongjo in 1796, is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[23] The entire city used to be encircled by the fortress walls,[103] but Suwon has long since expanded far beyond this boundary. There are four main gates in the walls,[23] and Haenggung Palace lies in the centre of the fortress.[104]

Hwaseong was built under the guidance of philosopher Jeong Yak-yong.[23] Workers were paid for their labour for one of the first times in Korea's history, corvée labour having been common previously.[105] Construction details were meticulously recorded in the text Hwaseong Seongyeok Uigwe (화성 성역 의궤).[106] This document was invaluable after the Korean War: reconstruction efforts from 1964 to the present day have relied heavily on this.[23]

|

|

|

Hyanggyo

[edit]Suwon Hyanggyo (수원향교; 水原鄕校) was a government-run school and Confucian ceremonial centre during the Goryeo and Joseon periods. During the Joseon Dynasty, it was the largest and oldest state school in Gyeonggi Province.[107] The school was originally built in 1291 beside Hwasan in Wau-ri, Hwaseong-gun. It was moved to its current location at 107–9 Hyanggyo-ro, Gyo-dong around 1795, when Hwaseong Fortress was built.[108] The school houses memorial tablets to Confucius, Mencius, and 25 Korean figures noteworthy to Confucianism.[109] It is open to the public on weekdays from 9 a.m. till 5 p.m., but it is closed at weekends.[108]

|

|

|

Bugugwon

[edit]

Bugugwon (부국원), also known as Suwon Gu Bugugwon, built prior to 1923, is a cultural centre at 130 Hyanggyo-ro, Gyo-dong. There is no record of the 85.95 m2 building's construction, but exterior photographs were published in 1923.[110] Under Japanese rule, the building was the headquarters of Bugukwon Co., Ltd., which sold agricultural products such as fertilizers.[110] After liberation, from 1952 to 1956, it temporarily housed the Suwon Court and the Public Prosecutor's Office.[110] From 1957 to 1960, it was used as the Suwon City Education Support Office,[110] and in 1974 the Republican Party used it as their Gyeonggi Province base.[110] In 1979, the Suwon Arts Foundation was based here,[110] and in 1981 it became an internal medicine clinic.[110] Since 2018, it has been a public cultural space.[111]

Adams Memorial Hall

[edit]Adams Memorial Hall served as a focal point for the independence movement. The building was constructed in 1923 under Pastor William Noble with funding from various sources, including a church in the United States, Suwon Jongno Church, and local residents. Here, independence activists including Park Seon-tae and Lee Deuk-su met weekly to discuss their activities.[112]

Culture and contemporary life

[edit]Housing

[edit]As is typical of urban South Korea, Suwon has many apartment complexes. The city has been affected greatly by real estate price fluctuations.[113]

Food

[edit]Suwon is known for Suwon galbi, a variation on beef ribs enjoyed throughout Korea.[114]

Sport

[edit]Suwon World Cup Stadium was built for the 2002 FIFA World Cup.[115] Today, it is home to the K League 2 team Suwon Samsung Bluewings. Local rivals Suwon FC and Suwon FC Women play in K League 1 and WK League respectively. They both play home matches at Suwon Sports Complex.[116][117]

Since 2013, Suwon has been home to the professional baseball team KT Wiz. The team played at Sungkyunkwan University until Suwon Baseball Stadium remodelling was completed in time for their elevation to the KBO League in 2015.[118] The stadium was previously the home of the Hyundai Unicorns, who folded after the 2007 season.[119]

Two of the Korean Basketball League and Women's Korean Basketball League's oldest teams, Samsung Thunders and Samsung Life Blueminx respectively, used to be based in Suwon. Samsung Thunders relocated to Jamsil Arena in Seoul in 2001,[96][97] while four years later, Samsung Life moved to Yongin.[98][99] Top-flight men's basketball returned to Suwon in 2021, when KT Sonicboom relocated from Busan to the renamed Suwon KT Sonicboom Arena (formerly Seosuwon Chilbo Gymnasium).[120]

The 5,145-capacity Suwon Gymnasium is home to the men's and women's V-League volleyball teams Suwon KEPCO Vixtorm and Suwon Hyundai Engineering & Construction Hillstate respectively.[121] The gymnasium staged the handball events in the 1988 Summer Olympics.[122] It also hosted handball and table tennis at the 2014 Asian Games[123] and hosted the 2010 Judo World Cup.[124][125][126]

Museums

[edit]Suwon has two national museums. The National Map Museum of Korea houses a collection of 33,598 maps.[127] It is located at 92 Worldcup-ro, Woncheon-dong. Admission is free, and the museum opens daily from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.[127] Suwon's second national museum, the National Agricultural Museum of Korea, opened by Seoho Lake in December 2022.[128] It is located at 154 Suin-ro, Seodun-dong, admission is free, and it is open daily from 10 a.m. till 6 p.m.[129]

There are also a number of smaller museums in Suwon. For example, Suwon Hwaseong Museum, at 21 Changnyong-daero, Maehyang-dong, features exhibits contextualising and explaining the construction of Hwaseong.[130] Another smaller museum, Haewoojae, has gathered some international attention.[131] Built privately in 2007 at 463 Jangan-ro, Imok-dong, this museum is dedicated to the history of toilets.[131] Ownership of Haewoojae was transferred to the city council in 2009.[132]

Libraries

[edit]Suwon Central Library opened in 1980 at 318 Paldalsan-ro, Gyo-dong.[133][134] Today, the city has 27 public libraries: seven in Gwonseon District, five in Jangan District, six in Paldal District, and nine in Yeongtong District.[133] The council also plans to build another in Imok-dong.[135]

Parks and gardens

[edit]Suwon has two municipal arboreta: Irwol Arboretum (일월 수목원) and Yeongheung Arboretum (영흥 수목원). These opened simultaneously on 19 May 2023 beside Irwol Reservoir and Yeongheung Park respectively.[136][137] The 10.15-hectare (25.1-acre) Irwol Arboretum features 429,000 plants of 52,000 species, while Yeongheung Arboretum hosts 118,000 plants of 42,000 species over 14.6 hectares (36 acres).[137] There are also 338 parks scattered through the city.[138] Some of these, e.g., Gwanggyo Lake Park, Seoho Park, Irwol Park, and Manseok Park, contain sizeable lakes.[139]

|

Street art

[edit]Haenggung-dong and Ji-dong in central Suwon are known for their murals,[140] while Haenggung-dong streets have a variety of other artistic features such as optical illusions.[141]

Media

[edit]Newspapers based in Suwon include the Kyeonggi Ilbo (경기일보) in Jangan District, and the Kyeongin Ilbo (경인일보) and Suwon Daily (수원일보) in Paldal District.[142]

National broadcaster KBS has a drama studio and art hall in Ingye-dong, Yeongtong District. These are open to visits by appointment.[143]

Cinemas

[edit]Suwon has several multiplex cinemas: three branches of CGV (in Ha-dong,[144] Ingye-dong,[144] and Jowon-dong[144]); four branches of Lotte Cinema (in Cheoncheon-dong,[145] Geumgok-dong,[145] Iui-dong,[145] and Seodun-dong[145]); and six branches of Megabox (in Gwonseon-dong,[146] Haenggung-dong,[146] Homaesil-dong,[146] Ingye-dong,[146] Jeongja-dong,[146] and Maesan-dong[146]). Other smaller cinemas, which may show fewer foreign films, include Cinema Town,[147] Taehan Theater,[147] Piccadilly Theater,[147] Jungang Theater,[147] Royal Theater,[147] Dano Theater,[147] and Dano Art Hall.[147]

Retail

[edit]

There are several major shopping centres across Suwon, e.g., AK Plaza and Lotte Mall at Suwon Station, and Avenue France[148] and Alleyway in Gwanggyo.[149] Another large centre, Starfield—incorporating its own library and a Megabox cinema—opened beside Hwaseo Station in January 2024.[150] This mall targets a younger customer base, and incorporates pop-up stores.[151] The first pop-up for the popular game 'Brawl Stars' was held here.[152] The warehouse-style discount store 'Traders' is located in the basement.[153]

|

Public toilets

[edit]In the early 2000s, Suwon City Council strove to improve the condition of its public lavatories, and afterwards ran guided tours of the municipal facilities.[154][155] Suwon has hosted several international conferences on toilet management,[156] and the World Toilet Association is based in the city.[157]

Transport

[edit]

Suwon Station is served by KTX and other trains on the Gyeongbu Line connecting Seoul to Busan.[158] From 1930 till 1972, the Suryeo Line also connected Suwon to Yeoju,[159] and from 1937 to 1996, the Suin Line ran from Suwon to Incheon.[159] The Suin Line has since been reconstructed as part of the Seoul Metro.[159][160] Today, three Seoul Metro lines (14 stations) serve Suwon,[161] and there are plans for network expansion. Construction of an extension of the Sinbundang Line to Homaesil is scheduled to begin in 2024.[162] Another planned line—the Dongtan–Indeogwon Line—should create several new stations in Suwon, but this has been delayed, prompting affected cities to call for urgent action.[163]

| Line | Station |

|---|---|

| Line 1 | Sungkyunkwan University (성균관대)[161] |

| Hwaseo (화서)[161] | |

| Suwon (수원)[161] | |

| Seryu (세류)[161] | |

| Shinbundang Line | Gwanggyo Jungang (광교중앙)[161] |

| Gwanggyo (광교)[161] | |

| Suin-Bundang Line | Cheongmyeong (청명)[161] |

| Yeongtong (영통)[161] | |

| Mangpo (망포)[161] | |

| Maetan-Gwonseon (매탄권성)[161] | |

| Suwon Hall]] (수원시청)[161] | |

| Maegyo (매교)[161] | |

| Suwon (수원)[161] | |

| Gosaek (고색)[161] | |

| Omokcheon (오목천)[161] |

Suwon is also served by two inter-city bus terminals with nationwide connections: Suwon Bus Terminal near Seryu Station,[164] and West Suwon Bus Terminal in Guun-dong.[165] Nevertheless, bus terminal passenger numbers are decreasing.[166] Suwon is also connected to Seoul and other nearby cities by city and express buses with departure points across the city.[167] In 2017, a new bank of bus stops opened at Suwon Station Transfer Center. This was built to alleviate pressure on existing bus and taxi stands across the tracks.[168] Another transfer centre is incorporated into Gwanggyo Jungang Station; this is underground, and bus stands feature screen doors.[169] Suwon has invested heavily in electric buses—in 2019, it built the country's largest bus charging station at 46 Gyeongsu-daero 1220beon-gil, Pajang-dong.[170]

Suwon is served by several expressways. The Yeongdong Expressway (50) passes through the city, with two exits within the city limits: North Suwon and East Suwon.[171] The Gwanggyo Sanghyeon exit on the Yongin–Seoul Expressway (171) is on Suwon's border with Yongin,[172] and the Pyeongtaek–Paju Expressway (17) also has an exit in Suwon (Geumgok).[173] The Suwon exit of the Gyeongbu Expressway (1) was renamed Suwon Singal in 2014 to reflect its actual location in Singal in neighbouring Yongin.[174]

Suwon has invested in ecological transport.[175] The city was the first place in Korea to introduce dockless public bicycles.[176] Traversing Suwon by bicycle is facilitated by numerous cycle paths beside the streams that cut through the city. In 2013, Suwon hosted the EcoMobility World Festival. For one month, streets in Haenggung-dong were closed to cars as a car-free experiment. Residents used non-motorized vehicles provided by the festival organizers.[177] The experiment was not unopposed.[178]

Military

[edit]Suwon Air Base in Jangji-dong, Gwonseon District was used by the United States Air Force during the Korean War, when it was the scene of the conflict's first aerial combat.[27] Today the base is under Republic of Korea Air Force jurisdiction, though it is still managed and maintained by the US military.[179] The US military also maintains Madison Site—a small signals unit with nearby helipad on Gwanggyosan.[180]

Fauna

[edit]While much of Suwon's wildlife can be expected to be similar to that in the surrounding province, two species are worth noting specifically in regard to the city. Firstly, an undisclosed location in Suwon appears to be Korea's first recorded breeding site of the white-breasted waterhen.[181] Secondly, the Suwon tree frog—one of three tree frogs to inhabit the Korean peninsula—[182][183] was discovered in Suwon around 1980, but due to urban sprawl it is no longer found in the city. It has, however, been found recently in Paju, Ansan, and Pyeongtaek (Gyeonggi Province); Eumseong (Chungcheongbuk-do); Gangwon-do; and North Korea.[184] The species is considered endangered.[185][182][183]

Notable people

[edit]Suwon was the birthplace of Choi Ru-baek (?–1205), famed for his filial piety,[186][187] and of his noble wife Yŏm Kyŏng-ae (염경애; 廉瓊愛, 1100–1146).[188] Also in ancient times, it was the home of Yi Ko (1341–1420), a Goryeo subject opposed to Joseon.[186] More recently, the eminent Silhak scholar and agricultural pioneer Woo Ha-yŏng (1741–1812) was born in the city[186]

Suwon was the birthplace of many independence activists during the Japanese colonial period. These include Im Myŏnsu (임면수; 林勉洙, 13 June 1874–29 November 1930),[186] Ch'a Injae (차인재; 車仁載, 1895–1971),[189][190] Kim Sehwan (1889–1945)[186] Kim Hyanghwa (1897–?),[191][186] Pak Sŏnt'ae (박선태; 朴善泰, 1901–1938),[186] Yi Sŏn'gyŏng (이선경; 李善卿, 1902–1921),[186] Ch'oe Munsun (최문순; 崔文順, 1903–?),[192] Kim Changsŏng (김장성; 金長星, 7 February 1913–9 March 1932),[186] and Hong Jong-cheol (홍종철; 洪鐘哲, 26 March 1920–22 July 1989).[186]

The influential feminist, painter, writer, poet, sculptor, and journalist Na Hye-sok (1896–1948) was also born in Suwon[193][186]

Artists from Suwon include Yoon Han-hŭm (윤한흠; 尹漢欽, 1923–22 August 2016).[194][195][196] and Kim Sung-bae (김성배; 金成培, 1954–).[197]

Sports players from Suwon include *Chung Hyeon (1996–, tennis),[198][199] Dong Hyun Kim (1981–, MMA)[200][201] Oh Kyo-moon (1972–, archery),[202] and Park Ji-sung (1981–, football). Park was born in Seoul but raised in Suwon, and in 2005, a city street was renamed after him.[203]

Classical musicians from Suwon include Han-na Chang (1982–, conductor, cellist),[204][205] Stella Hanbyul Jeung (정한별, opera singer),[206] and Seol Yoeun (설요은, 2012–, violinist).[207]

Suwon is also the birthplace of many popular musicians, e.g., Im Chang-kyun (stage name I.M, 1996–) Jeon Ji-yoon (1990–),[208] Jo Kwon (1989–), Kim Myung-jun (stage name MJ, 1994–), Kim Yu-gwon (stage name U-Kwon, 1992–),[209] Lee Chang-sub (1991–), Lee Dong-hun (이동훈, 28 February 1993–), Lee Jin-ki (stage name Onew, 1989–),[210] Lee Ju-eun (1995–), Shin Dong-hee (stage name Shindong, 1985–),[211] Yoo Jeongyeon (1996–),[212] Yoo Ji-min (stage name Karina, 2000–),[213][214] and Yoon Bo-mi (1993–).[215][216]

Actors from Suwon include Lee Jong-suk (1989–)[217] Park Hae-soo (1981–),[218][219] Ryu Jun-yeol (1986–),[220][221] Song Kang (1994–),[222] and Yoo Hyun Young (1976–).

Pastor Kim Jang Hwan (known as Billy Kim, 1934–) is also from Suwon. He is a former president of the Baptist World Alliance, and president of the Far East Broadcasting Company[76]

The presenter and columnist Sam Oh (1980–) was also born in the city.[223]

Sister cities

[edit]Suwon is twinned internationally with:[224]

Asahikawa, Japan (1989)

Asahikawa, Japan (1989) Jinan, China (1993)[224]

Jinan, China (1993)[224] Townsville, Australia (1997)[224]

Townsville, Australia (1997)[224] Bandung, Indonesia (1997)[224]

Bandung, Indonesia (1997)[224] Yalova, Turkey (1999)[224]

Yalova, Turkey (1999)[224] Cluj-Napoca, Romania (1999)[224]

Cluj-Napoca, Romania (1999)[224] Toluca, Mexico (1999)[224]

Toluca, Mexico (1999)[224] Fez, Morocco (2003)[224]

Fez, Morocco (2003)[224] Hải Dương Province, Vietnam (2004),[224]

Hải Dương Province, Vietnam (2004),[224] Siem Reap Province, Cambodia (2004)[224]

Siem Reap Province, Cambodia (2004)[224] Nizhny Novgorod, Russia (2005)[224]

Nizhny Novgorod, Russia (2005)[224] Curitiba, Brazil (2006)[224] and

Curitiba, Brazil (2006)[224] and Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany (2015)[224]

Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany (2015)[224] Phoenix, United States (2021)[224]

Phoenix, United States (2021)[224] Toury, France (2023)[224]

Toury, France (2023)[224] Mississauga, Canada (2023)[224]

Mississauga, Canada (2023)[224]

Suwon also twinned internationally with Jeju (1997),[225] Pohang (2009),[225] Jeonju (2016),[225] and Nonsan (2021).[225]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Population statistics". Korea Ministry of the Interior and Safety. 2024.

- ^ a b c 나무·꽃·새·주 상징종 [Trees, Flowers, Birds, and City Symbols] (in Korean). Suwon City Council. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ 우편번호 개요 [Postal code overview] (in Korean). Korea Post. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d 월별인구현황 [Population Status by Month] (in Korean). Suwon City Council. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ "Administrative District & Population". Ulsan Metropolitan City Council. 28 February 2023. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ "PM: 4 Cities to be Given New Autonomous Status Hold Greater Responsibility". KBS World. 3 January 2022. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Suwon invites visitors to city of heritage, festivities". The Korea Herald. 1 May 2016. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Park, Hyemi (11 March 2016). "Suwon celebrates its past while looking ahead". Korea JoongAng Daily. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Suwon Hwaseong fortress celebrates 220th year". Korea JoongAng Daily. 21 February 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ "Samsung Electronics stays atop S. Korea's top 500 firms' list". Yonhap News Agency. 10 May 2023. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ Song, Sung-hoon (22 February 2016). "Samsung Electronics leaves Seoul headquarters". Maeil Business News. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ Stek, Pieter (2017). "The Strategic Alliance Between Sungkyunkwan University and the Samsung Group: South Korean Exceptionalism or New Global Model?". Triple Helix Association. Archived from the original on 29 April 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Club: Suwon Samsung Bluewings". Goalzz. Kooora. Archived from the original on 8 June 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ Stokkermans, Karel (16 October 2014). "Asian Club Competitions 2000/01". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ "Blue Wings flying high". BBC Sport. 24 July 2002. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ a b 수원시통계 [Suwon City Statistics] (in Korean). Archived from the original on 30 January 2011.

- ^ "Suwon Tour: Hwaryeongjeon, Haeng-gung and Suwon Fortress". Korea.net. 31 March 2010. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z 최, 운식; 이, 도남. 수원시 (水原市) [Suwon City]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ a b c 김, 선주. 모수국 [Mosukuk]. 디지털양주문화대전. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d Lee, Ki-Moon; Ramsey, S. Robert (2011). A History of the Korean Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 9781139494489.

- ^ Webster, Hugh A. (1877). "Corea". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Vol. 6 (9 ed.). p. 390. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ a b Noh, Hyeonkyun; Park, Woo; Seo, Boram (2021). "A Fortress Made in Heaven (Namhansanseong of Gwangju) and the City of a King's Dreams (Hwaseong Fortress of Suwon)". The Review of Korean Studies. 24 (2): 299–331. Archived from the original on 27 June 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Hwaseong Fortress". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ 화성시 연혁 [History of Hwaseong City]. Hwaseong City Council (in Korean). Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ "49th Wing history". US Air Force. Archived from the original on 18 June 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ a b Frace, Robert R. (21 June 2013). "Suwon history goes far beyond Korean War". United States Army. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Korean Air Battles". Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Y'Blood, William T. "The Korean Air War". US 7th Air Force. Archived from the original on 21 June 2023. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ "Suwon captured by invaders". The West Australian. Perth, WA. 5 July 1950. p. 1. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ McDonald, Hamish (15 November 2008). "South Korea owns up to brutal past". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, NSW. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Nichols, Donald (1981). How many Times Can I Die: The life Story of a Special Intelligence Agent. Pensacola, FL: Brownsville Printing. p. 128.

- ^ Kim, Dong-Choon (2007). "Chapter 4: The war against the "enemy within": Hidden massacres in the early stages of the Korean War". In Shin, Gi-Wook; Park, Soon-Won; Yang, Daqing (eds.). Rethinking Historical Injustice and Reconciliation in Northeast Asia: The Korean experience. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 75–93. ISBN 978-0-415-77093-4.

- ^ Hanley, Charles J.; Chang, Jae-Soon (5 July 2008). "AP: U.S. Allowed Korean Massacre In 1950". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ "Knocked out T-34 at Suwon". Manchester Regiment. 5 May 2005. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Thomas, Nigel; Abbott, Peter; Chappell, Mike (27 March 1986). The Korean War 1950–53. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 9780850456851.

- ^ Yenne, Bill (2020). Aces: True stories of victory and valor in the skies of World War II. Book Sales. p. 40. ISBN 9780160359583.

- ^ "South Korea–France–Suwon". Korean War Memorials. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "French military graves in South Korea". French Ministry of Armed Forces (Ministère des Armées). Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "South Korea–France–Suwon". Suwon City Council (in Korean). Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ 대통령령 제159호: 시·도의관할구역및구·군의명칭·위치·관할구역변경의건 [Presidential Decree 159: Change in the Name, Location, and Jurisdiction of Cities/Provinces and Districts/Counties]. Office of the President, Republic of Korea (in Korean). Ministry of Government Legislation, Republic of Korea. 13 August 1949. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ 법률 제1175호: 시·군관할구역변경및면의폐치에관한법률 [Law No. 1175: Act on Change of Districts and Abolition of Municipalities]. National Legal Information Centre (in Korean). Ministry of Government Legislation. 21 November 1962. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ 대통령령 제11027호: 시·군·구·읍·면의관할구역변경및면설치등에관한규정 [Presidential Decree No. 11027: Regulations on Change of Jurisdiction of Si/Gun/Gu/Eup/Myeon and Establishment of Myeon]. National Legal Information Centre (in Korean). Ministry of Government Legislation. 10 January 1983. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ 대통령령 제12007호: 시·군·구·읍·면의관할구역변경및면의명칭변경에관한규정 [Presidential Decree No. 12007: Regulations on Change of Jurisdiction of Si/Gun/Gu/Eup/Myeon and Change of Name of Myeon]. National Legal Information Centre (in Korean). Ministry of Government Legislation. 3 December 1986. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ 이씨들이 논을 많이 경작했다 해 '이성벌' [The Lees Cultivated a Lot of Rice at Lee Seongbeol]. The Suwon Daily (in Korean). 13 June 2020. Archived from the original on 14 May 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ 대통령령 제14434호: 시·군·자치구의관할구역변경에관한규정 [Presidential Decree No. 14434: Regulations on Change of Jurisdiction of Si/Gun/Autonomous Gu]. National Legal Information Centre (in Korean). Ministry of Government Legislation. 22 December 1994. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ 대통령령 제19875호: 전라남도 나주시 등 4개 시·군의 관할구역 변경에 관한 규정 [Presidential Decree No. 19875: Regulations on Change of Jurisdiction of 4 Si and Gun including Naju, Jeollanam-do]. National Legal Information Centre (in Korean). Ministry of Government Legislation. 8 February 2007. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ Roh, Hogeun (19 April 2007). 수원.용인 경계일부-어정동 분동 등 관할구역 변화 [Part of the Border Between Suwon and Yongin, and Changes in Jurisdictions such as Eojeong-dong and Bun-dong]. Newsis (in Korean). Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ 대통령령 제30036호: 경기도 수원시와 용인시의 관할구역 변경에 관한 규정 [Presidential Decree No. 30036: Regulations on Change of Jurisdiction between Suwon and Yongin, Gyeonggi-do]. National Legal Information Centre (in Korean). Ministry of Government Legislation. 13 August 2019. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ Lee, Jaesang (6 August 2019). 부산·수원·용인 등 관할구역 변경…불합리한 행정구역 조정 [Changes in Jurisdictions such as Busan, Suwon, and Yongin: Unreasonable Administrative District Adjustment]. News1 (in Korean). Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ 대통령령 제30794호: 경기도 수원시와 화성시의 관할구역 변경에 관한 규정 [Presidential Decree No. 30794: Regulations on Change of Jurisdiction between Suwon and Hwaseong, Gyeonggi-do]. National Legal Information Centre (in Korean). Ministry of Government Legislation. 23 June 2020. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "31 City/County Map". Gyeonggi-do Provincial Council. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "Measure distance on a map". Free Map Tools. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ 사사동의 칠부산 [Sasa-dong's Chilbosan]. Banwol Newspaper (in Korean). Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Oh, Inseop (1972). 水原 地質圖幅說明書 (수원 지질도폭설명서) [Suwon Geological Map Manual] (in Korean). Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ^ 광교산 (光橋山) [Gwanggyosan]. Korean Mountaineering Association (in Korean). 1999. Archived from the original on 6 September 2007. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Kim, Jinsun; Lee, Jimin; Park, Minji; Min, Joong-Hyuk; Lee, Jong Mun; Jang, Heeseon; Na, Eun Hye (2024). "The Impact of Non-Point Source (NPS) Management on Non-Point Source Reduction and Water Cycle Improvement in an Urban Area". Sustainability. 16 (3): 1248. doi:10.3390/su16031248.

- ^ Choi, Hyeonmi; Cho, Yong-Chul; Kim, Sang-Hun; Yu, Soon-Ju; Kim, Young-Seuk; Im, Jong-Kwon (2021). "Water Quality Assessment and Potential Source Contribution Using Multivariate Statistical Techniques in Jinwi River Watershed, South Korea". Water. 13 (21): 2976. doi:10.3390/w13212976.

- ^ Seo, Anna; Lee, Kyungeun; Kim, Bomchul; Choung, Yeonsook (2014). "Classifying plant species indicators of eutrophication in Korean lakes". Paddy and Water Environment. 12 (Suppl1): 29–40. Bibcode:2014PWEnv..12S..29S. doi:10.1007/s10333-014-0437-z. S2CID 254162717. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ 축만제 (祝萬堤) [Chungmanje]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ Park, Su-cheol (21 December 2010). 밤밭저수지 주변 '생태공원' 만든다 ['Ecology Park' to be created around Bambat Reservoir] (in Korean). Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ 만석거 (萬石渠) [Manseokkeo]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ "2 Korean reservoirs registered as world heritage irrigation sites". Yonhap News Agency. 11 October 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ 의왕시, 지역 경계조정은 레일바이크 추진 꼼수 [Uiwang Regional Boundary Adjustment is a Trick to Promote Rail Bikes]. Incheon Ilbo (in Korean). 12 March 2012. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "Climate: Gyeonggi-do". Climate Data. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "South Korea steps up flood rescue". BBC News. 9 August 1998. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Torrential rains kill many, cause widespread damage". Al Jazeera. 6 August 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Climatological Normals of Korea (1991–2020)" (PDF) (in Korean). Korea Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ 순위값 - 구역별조회 [Ranks by District] (in Korean). Korea Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ "Climatological Normals of Korea" (PDF). Korea Meteorological Administration. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ 수원시 행정구역 [Suwon Administrative Divisions] (in Korean). Suwon Council. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ "Gov't to Tackle Traffic Congestion in 37 New Town Areas". Korean Broadcasting System. 12 October 2022. Archived from the original on 14 May 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ "MVRDV architects wins Gwanggyo power centre competition in South Korea". Design Boom. 4 December 2008. Archived from the original on 14 May 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ "Population Census". Statistics Korea.

- ^ Acta Apostolicae Sedis [Proceedings of the Apostolic See] (PDF) (HI, v. - N 11) (in Latin). Holy See. 31 August 1964. p. 661–662. Retrieved 29 May 2023. Archived 15 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cheney, David M. "Diocese of Suwon". Catholic Hierarchy. Archived from the original on 11 August 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Billy Kim". Christian Post. 22 November 2002. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ Mallory, Tammi (5 February 2002). "Billy Kim: from 'lowly houseboy' to Baptist World Alliance president". Archived from the original on 20 June 2023. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ 미륵당 [Mireukdang]. Suwon City Council Council (in Korean). Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Jeong, Heunggyo (4 March 2015). 파장동만이 아니라 수원전체의 평안을 위한 조상의 마음이 엿보이는 [A Glimpse of Our Ancestors' Desire for Peace, Not Only in Pajang-dong, but Throughout Suwon]. Suwon Internet News (in Korean). Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Joo, Youngha; Kwon, Youngsang (2015). "Urban street greenery as a prevention against illegal dumping of household garbage—A case in Suwon, South Korea". Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 14 (4): 1088–1094. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2015.10.001. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- ^ "Number of Crime Occurrence by Crime Type and Crime Place (1994~)". Statistics Korea. 20 December 2022. Archived from the original on 8 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ "Interview of the Outgoing Dean Lee Suk-ha". Seoul National University. 20 July 2021. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ 관내학교(지역구별) [Local Schools (by Region)]. Gyeonggi-do Suwon Office of Education (in Korean). Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ Kim, Mi-Kyung; Kim, Eun-Jin (2022). "A Study on the Development of Art Therapy Program for Children with Disabilities in Special Schools—Focusing on Jahye School in Gyeonggi-do". Art Culture Research (in Korean). 22: 101–133. doi:10.18707/jacs.2022.04.22.101. S2CID 249321419. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ "Samsung Smart School Greets the World at the 2018 APEC Future Education Forum". Samsung Newsroom. 14 December 2018. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ Park, Mina (27 June 2019). 고교 졸업 앞둔 장애학생 '새로운 내일' 응원 [Supporting Imminent High School Graduates with Disabilities for a 'New Tomorrow']. Kyunggi News (in Korean). Archived from the original on 9 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ 특수학급연혁 [Special Education History]. Suwonbuk Middle School (in Korean). Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Kim, Hyesuk (24 July 2023). 계명고 정규졸업장 받는 '성인반' 운영 중 [Adult High School Diploma Classes Running at Kyemyung High School]. Kyunggi Nambu News (in Korean). Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "Gyeonggi Suwon International School". International Schools in Korea. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "Suwon Chinese International School". International School Information, Korean Government. Archived from the original on 30 March 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ "Water management in Korea: From goals to action". OECD. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ Park, Hyunju; Han, Mooyoung; Kim, Tschung-il (2022). "Urban Water Management Using Water Self-sufficiency". Journal of the Korean Society for Environmental Technology. 23 (5): 251–257. doi:10.26511/JKSET.23.5.1. S2CID 256288864. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ Lee, Hyung-Woo; Lee, Tae-Jung; Yang, Sung-Su; Kim, Dong-Sool (2008). "Identification of atmospheric PM10 sources and estimating their contributions to the Yongin–Suwon bordering area by using PMF". Journal of the Korean Society for Atmospheric Environment (in Korean). 24 (4): 439–454. doi:10.5572/KOSAE.2008.24.4.439. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ Is the grass really greener? Investigating the industrial eco strategies of South Korea (PDF) (Report). Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge. 2012. p. 40. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "History of Bluewings". Suwon Samsung Bluewings. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ a b Lee, Changho (3 May 2001). 삼성 연고지 서울 이전 [Relocating to Samsung's Seoul Home]. The Chosun Daily (in Korean). Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ a b Hwang, Seonhak (2 June 2001). 프로농구 삼성-SK 서울에 공동 연고지 [Professional Basketball Teams Samsung and SK to Move to Joint Location in Seoul]. Kyeonggi Daily (in Korean). Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ a b Kang, Hocheol (22 June 2005). 여자농구 '틈새 공략' [Women's Basketball in 'Niche Attack']. Chosun Daily (in Korean). Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ a b Woo, Seung-o (22 June 2005). 여 프로농구 삼성생명 "이젠 용인시민 위해 뛰어요" [Female Professional Basketball Samsung Life: "Now I'm Running for the People of Yongin"]. The Kyeonggi Daily (in Korean). Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "SKC Co. Ltd". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ Choi, Jasmine (31 January 2014). "Samsung SDI Begins Full-scale Shipment of 'Dream Battery' Solid-state Batteries". Business Korea. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "Samsung Electro-Mechanics". Forbes. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "Adventure in Suwon Hwaseong Fortress". Korean Cultural and Information Service. 23 August 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ "Hwaseong Haenggung: Introduction". Suwon Cultural Foundation. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Lovins, Christopher (2014). Testing the limits: King Chŏngjo and royal power in late Chosŏn (PhD). University of British Columbia. p. 146. doi:10.14288/1.0103420. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ Pölking, Florian (2017). "The Status of the Hwaseong seongyeon uigwe in the History of Architectural Knowledge: Documentation, Innovation, Tradition". The Korean Journal for the History of Science. 39 (2): 257–291. doi:10.36092/KJHS.2017.39.2.257. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ "Asian Historical Architecture: Suwon, Korea, South". Oriental Architecture. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Suwonhyanggyo Confucian School". Korea Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ "Suwonhyanggyo Confucian School". Trippose. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g 수원 구 부국원 (水原 舊 富國園) [Suwon Gu Bugugwon] (in Korean). Korea National Heritage Online. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ 자취수원의 근현대사가 응축된 건물 - 수원 구 부국원 [Suwon Gu Bugugwon: A Building Where the Past and Present Collide] (in Korean). The Federation of Korean Cultural Centers. Archived from the original on 25 June 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ "Adams Memorial Hall". Cultural Heritage Administration. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ 1년 만에 아파트값 6억 뚝 떨어져…수원 집주인 '비명' [Apartment Prices Fell by 600 Million Won in Just One Year... Suwon Landlords Are 'Screaming']. Korea Economy {The Korea Economic Daily. 26 November 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "Suwon Wang Galbi Street". Gyeonggi Grand Tour. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Haruo, Nogawa; Toshio, Mamiya (25 April 2002). "Chapter 11: Building mega-events—Critical reflections on the 2002 World Cup infrastructure". In Horne, John; Manzenreiter, Wolfram (eds.). Japan, Korea and the 2002 World Cup. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780203603376.

- ^ Farrell, Andrew (14 March 2023). "Groundhopper's guide to..... Suwon Sports Complex". K League United. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Kim, Gaeul (21 December 2023). 수원월드컵경기장, 수원FC-수원 삼성 '한 지붕 두 가족' 공존할까 [Suwon World Cup Stadium: Will Suwon FC and Suwon Samsung Coexist as 'Two Families Under One Roof'?]. Chosun Daily (in Korean). Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Jeong, Jingu (10 April 2014). KT 위즈, 화장실이 필요해 [KT Wiz Needs a Lavatory]. SBS News (in Korean). Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Kim, Tong-hyung (7 October 2007). "Unicorns play last game". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ 부산 KT 프로농구단은 없습니다, 앞으로는 수원 KT입니다 [Professional Basketball Team Busan KT Ceases to Exist: Now Known as Suwon KT]. JoongAng Ilbo (in Korean). 8 June 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "Suwon Gymnasium". Volleybox. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ 1988 Summer Olympics official report, Volume 1, Part 1 (PDF) (Report). Seoul Olympic Organizing Committee. 30 September 1989. p. 195. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "FACTBOX-Factbox on sports at the 2014 Asian Games in Incheon". Reuters. 8 September 2014. Archived from the original on 29 April 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ "World Cup Suwon 2010". International Judo Federation. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Silver for Briton Gemma Howell at Korea World Cup". BBC Sport. 3 December 2010. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ 왕기춘, 월드컵 우승 '런던 가자!' [World Cup Winner Wang Ki-Chun, Let's Go to London!]. KBS News (in Korean). 3 December 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ a b "The National Map Museum of Korea". National Geographic Information Institute. Archived from the original on 28 July 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "Nat'l Agriculture Museum opens". Yonhap News Agency. 15 December 2022. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ 관람안내 [Viewing Guide]. Agricultural Museum of Korea (in Korean). Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "Exhibition on royal procession". The Korea Times. 6 October 2015. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ a b "'World's first toilet theme park' opens in South Korea". BBC News. 9 November 2012. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "Haewoojae Museum (Mr. Toilet House) (해우재)". Korea Tourist Organization. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ a b 수원시 도서관 사업소 [Suwon Library Office]. Suwon Library Office (in Korean). Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ 중앙도서관 [Central Library]. Suwon Library Office (in Korean). Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ 이목지구 근린공원 52 내 도서관 조성사업 설계공모 [Library Design Competition in Park 52]. Masilwide (in Korean). 4 May 2021. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ 수원 '일월수목원'·'영흥수목원' 개원 [Suwon Irwol and Yeongheung Arboreta Open]. KBS News (in Korean). 19 May 2023. Archived from the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ a b Bae, Taesik (23 May 2023). 자연과 더 가깝게…수원(일월·영흥)수목원 '활짝' [Closer to Nature: A Stroll in Suwon's Irwol and Yeongheung Arboreta]. Seoul Daily (in Korean). Archived from the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ 수원시 공원현황 [Suwon Park Status]. Suwon City Council. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Koh, Seongjae (20 August 2002). 수원市 11개 저수지 수질개선 나서 [Water Quality in 11 Suwon Reservoirs Improve]. Chosun Daily (in Korean). Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Holden, Trent (28 August 2015). "A guide to South Korea's most charming mural villages". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ "Haenggungg [sic] Street". Suwon Cultural Foundation. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ "Top newspapers in Korea". 4 International Media and Newspapers. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ KBS 수원센터 [KBS Suwon Centre]. Korean Broadcasting System (in Korean). Archived from the original on 5 July 2023. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ a b c 극장 [Theatres]. CGV (in Korean). Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d 영화관 [Cinemas]. Lotte Cinema (in Korean). Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f 전체극장 [All Cinemas]. Megabox (in Korean). Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The 5 Best Suwon Movie Theaters (with Photos)". Tripadvisor. Archived from the original on 5 May 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ Park, Haesik (27 April 2020). 광교 아브뉴프랑, 오픈 5주년 감사 이벤트 [Five-Year Anniversary Event at Avenue France, Gwanggyo]. The Dong-A Ilbo (in Korean). Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ Park, Seonggyu (1 May 2019). '앨리웨이 광교' 그랜드 오픈 [Grand Opening of Alleyway, Gwanggyo]. Seoul Economic (in Korean). Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ Seo, Ji-eun (24 January 2024). "From a sky-high library to luxury fitness, Starfield Suwon beckons youthful explorers". Korea JoongAng Daily. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ Lee, CHae Hyun (31 March 2024). "Suwon Starfield targets Gen MZ". HoyeongLee.

- ^ Lee, Chae Hyun (31 March 2024), "Pop-up store in Suwon Starfield", 스타필드 수원, 전면에 게임 '브롤스타즈' 내세웠다, Seongnam: Lee Du Hyeon

- ^ Lee, Chae Hyun (31 March 2024). "Traders in Suwon Starfield". Yoon Uyeol.

- ^ "Lavish Latrines, Pretty Potties". Los Angeles Times. 6 June 2002. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ Schuman, Michael; Choi, Hae Won (26 November 1999). "Suwon's Restrooms, Once the Pits, Are Now Flush With Tourists". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ "General Assembly/International Toilet Culture Conference". World Toilet Association. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "History". World Toilet Association. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ "Suwon to Busan High-Speed Train". Korea Trains. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ a b c Choi, Ho-jin. "Suwon: The past and present of Suwon Station (1)". Gyeonggi Culture. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ Burroughs, David (15 September 2020). "Final phase of Korea's Suin Line complete". International Railway Journal. Simmons-Boardman Publishing. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p 철도네트워크 [Railway Network]. Suwon City Council. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Kang, Gapsaeng (28 December 2021). 신분당선 광교~호매실 연장선 기본계획 확정...2024년초 착공 [Shinbundang Line Gwanggyo–Homaesil Extension Finalised: Construction to Start in Early 2024]. Korea JoongAng Daily (in Korean). Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ Park, Seonsik (1 March 2023). 동탄인덕원 복선전철 건설사업 조기 착공해야 [Dongtan–Indeokwon Double-Track Subway Construction Must Begin Promptly]. Jeonguk Mail Sinmun (in Korean). Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ "Suwon Bus Terminal". Buspia (in Korean). Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "SeoSuwon Bus Terminal". Seosuwon Terminal (in Korean). Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Kim, Gyeongtae (6 May 2023). 경기도 버스터미널 이용객 '반토막'…노선도 172개 사라졌다 [Gyeonggi-do Bus Terminal Users 'Halve': 172 Routes Disappear]. Yonhap News Agency (in Korean).

- ^ "Gyeonggi Bus Information". Gyeonggi Bus. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Tebay, Andy (26 June 2017). "Transfer hub opens at Suwon Station including new bus interchange". Archived from the original on 8 May 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ Nikola (19 February 2016). "Underground Bus Station, Future of Bus Transit?". Archived from the original on 8 May 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ Hong, Yongdeok (10 December 2019). "Suwon builds S. Korea's largest electric bus charging station". The Hankyoreh. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ 영동고속도로 북수원IC~동수원IC부가차로설치공사 도로구역결정 고시 [Announcement of Additional Lane Construction for Yeongdong Expressway Between North Suwon IC and East Suwon IC]. Ministry of Transport. 16 October 2009. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ 도로이용안내 / IC 이용안내 [Road and IC Usage Information]. Suwon Ring Road Corporation. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ 하행 금곡IC 전 차로 차단 및 노면 긴급 보수 공사 안내(당수동 LH 굴착공사) [Information on Blocking All Lanes of Southbound Geumgok IC and Emergency Roadworks (Dangsu-dong LH excavation work)]. Kyunggi South Road Co. Ltd. 30 May 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Kwon, Hyeokjun (22 April 2015). 수원신갈IC 시설물 교체공사 완료 [Suwon Singal IC Facility Replacement Work Completed]. Kyeonggi Ilbo (in Korean). Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ Bak, Se-hwan (1 February 2018). "Suwon seeks to become Korea's 'eco-capital': Environmental activist-turned-mayor sets new examples of how green policies revitalize cities". The Korea Herald. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Kim, Sukhee; Oh, Sei-Chang; Choi, Keechoo (30 April 2019). "Bilantravel pattern analysis for station bike sharing system in Suwon". Journal of Korean Society of Transportation (in Korean). 37 (2): 110–123. doi:10.7470/jkst.2019.37.2.110. S2CID 210784252. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Strother, Jason (30 September 2013). "Locals applaud car-free month in Korean city". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ Kim, Suk-Hui; Lee, Seung-Gyu (2014). "An Analysis of Residential Satisfaction at The Ecomobility World Festival 2013 Suwon". Transportation Technology and Policy (in Korean). 11 (4): 64–72. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ "Suwon Air Base". Global Security. Archived from the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ Satkowski, Stephen (15 October 2014). "District engineers ensure water keeps flowing at Madison Site". US Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ "Birds Korea's Bird News August 2008". Birds Korea. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ a b Borzée, Amaël; Kosch, Tiffany A.; Kim, Miyeon; Jang, Yikweon (2017). "Introduced bullfrogs are associated with increased Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis prevalence and reduced occurrence of Korean treefrogs". PLOS ONE. 12 (5): e0177860. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1277860B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177860. PMC 5451047. PMID 28562628.

- ^ a b 토종 양서류 '수원청개구리' 북한에도 산다…충남·전북에선 신종 발견 [The Native Amphibian 'Suwon Tree Frog' Also Lives in North Korea… New Species Discovered in Chungnam and Jeonbuk]. Donga Science (in Korean). 26 June 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ "Protection of endangered species". Korean Broadcasting System. 19 June 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ Park, Il-Kook; Park, Daesik; Borzée, Amaël (2021). "Defining conservation requirements for the Suweon Treefrog (Dryophytes suweonensis) using species distribution models". Diversity. 13 (2): 69. doi:10.3390/d13020069.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k 수원의 인물 [People from Suwon]. Suwon City Council (in Korean). Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ 고려 전기에, 기거사인, 한림학사 등을 역임한 문신. [Civil Servant Who Served as Gigeosain and Hallimhaksa During the Early Goryeo Period]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). National Institute of Korean History. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ 염경애 묘지 [Tomb of Yeom Gyeongae]. History Net (in Korean). National Institute of Korean History. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ 차인재 여성 독립유공자 외손녀를 만나다 [Meeting the Granddaughter of Female Independence Activist Cha Injae]. Korean National Association Memorial Foundation (in Korean). Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Yang, Hundo (7 November 2022). '사진 신부'를 선택한 독립운동가 차인재 [Cha In-jae, an Independence Activist Who Chose to Be a 'Photo Bride']. Incheon Daily (in Korean). Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Gisaeng took to streets against Japan". Korea JoongAng Daily. 26 February 2009. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ Jeong, Changgyu (27 June 2022). 수원 출신 여성독립운동가를 만나다…수원박물관·경기도여성비전센터, 온라인 교류전 개최 [Meet a Female Independence Activist from Suwon: Suwon Museum and Gyeonggi Women's Vision Center Hold Online Exchange Exhibition]. Kyeonggi News (in Korean). Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ Kiaer, Jieun; Yates-Lu, Anna; Mandersloot, Mattho (15 September 2021). On Translating Modern Korean Poetry. Taylor & Francis. p. 157. ISBN 9781000438765.

- ^ "Suwon Hwaseong Museum Planned Exhibitions". Suwon Hwaseong Museum. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ Kim, Chungyeong (5 April 2021). 화성복원사업 밑그림 된 윤한흠 선생의 수원 옛 그림 [Old Picture of Suwon by Yun Hanheum, Who Documented the Hwaseong Restoration Project] (in Korean). Archived from the original on 5 July 2023. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ Kim, Uyeong (25 August 2016). 모교에 세워진 고 윤한흠 선생 동상 [Statue of the Late Yun Hanheum Erected in Alma Mater]. Suwon City Council (in Korean). Archived from the original on 5 July 2023. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ "Upcoming exhibitions". Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ "Hyeon Chung". ATP Tour. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ Lee, Minji (25 January 2018). "Chung Hyeon: The Korean tennis star making history". BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ "Kim Dong-hyun". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on 14 June 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ Gerbasi, Thomas (26 November 2015). "Dong Hyun Kim: The long road to Seoul". Archived from the original on 14 June 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ Choi, Jongsik (23 September 2000). 양궁 오교문선수집 감격의 눈물바다 [Archer Oh Kyo-moon's House: A Sea of Tears]. Kyeonggi Daily (in Korean). Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ Yu, Sinjae (12 June 2005). 수원시 '박지성길' 만든다 [Suwon City Constructs 'Park Ji-Sung Road']. The Hankyoreh (in Korean). Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "Han-Na Chang Official Biography". Han-na Chang Music. 2021. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ Lee, Hyo-won (1 November 2009). "Chang Han-na Finds Brahms Through Looking-Glass". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ "Stella Hanbyul Jeung". 2023. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ "The 18th Emirates International Peace Music Festival". Embassy of the Republic of Korea to the United Arab Emirates. 21 October 2022. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ "Ji-Yoon Jeon". Internet Movie Database (IMDB). Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ "U-Kwon profile". K-pop Music. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ Shin, Min-hee (13 April 2022). "Onew is back with another solo debut after three years". Korea JoongAng Daily. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Koh, Lydia (27 June 2020). "Super Junior's Shindong shares why his wedding engagement did not work out". The Independent Singapore. Archived from the original on 14 June 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ Jin, Byeonghun (9 September 2022). 트와이스 정연 살·건강 근황 걱정? "이 재미난 얼굴 보세요" [Twice's Jeongyeon Worried about Her Current Life and Health? "Look at This Funny Face."]. NBN TV (in Korean). Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ 카리나 (에스파) [Karina (Aespa)]. Marie Claire (in Korean). Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ Jeong, Aram (8 July 2021). 카리나(aespa) [Karina (Aespa)]. Hanryu Times (in Korean). Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ 수원시 영상홍보대사에 '토박이' 에이핑크 윤보미 [Suwon's Video Ambassador 'Native' Yoon Bo-mi of Apink]. KBS Radio Korean (in Korean). 21 March 2017. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Lee, Kwanju (21 March 2017). 에이핑크 윤보미, 수원시 영상홍보대사 위촉 [Apink's Yoon Bomi Appointed Video Ambassador for Suwon]. Kyeonggi Daily (in Korean). Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ 이종석 [Lee Jong-suk]. KBS Star Box (in Korean). Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ Lee, Jae-lim (18 April 2022). "Park Hae-soo continues to thrive on Netflix". Korea JoongAng Daily. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ "Park Hae-soo". Television Academy. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ "Ryu Jun-Yeol". Internet Movie Database (IMDB). Archived from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ "Suwon's son Ryu, the leading actor in 'Please Respond, 1988'". Suwon Center for International Cooperation. 14 April 2016. Archived from the original on 13 June 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ Lee, Jae-lim (14 March 2022). "Song Kang continues to flaunt his good looks on the small screen". Korea JoongAng Daily. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Santos, Marielle C. (6 October 2006). "Oh! It's Sam". Philippine Star. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p 국제자매·우호도시 [International Sister/Friendship Cities]. Suwon Center for International Cooperation (in Korean). Archived from the original on 26 November 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d 국내자매도시 [Domestic Sister Cities]. Suwon City Council (in Korean). Retrieved 18 January 2024.

External links

[edit]- Suwon City Council (in Korean)

- Suwon F.C (in Korean)

- Suwon Samsung Bluewings (in Korean)

- KT Wiz (in Korean)

- 신광교클라우드시티 Scheduled for August 2029

- 용인시청 (yongin city hall)