International sanctions against Iran

| Part of a series on the |

| Nuclear program of Iran |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Facilities |

| Organizations |

| International agreements |

| Domestic laws |

| Individuals |

| Related |

There have been a number of international sanctions against Iran imposed by a number of countries, especially the United States, and international entities. Iran was the most sanctioned country in the world until it was surpassed by Russia, following Russia's invasion of neighboring Ukraine in February 2022.[1]

The first sanctions were imposed by the United States in November 1979,[2] after a group of radical students seized the American Embassy in Tehran and took hostages. These sanctions were lifted in January 1981 after the hostages were released, but they were reimposed by the United States in 1987 in response to Iran's actions from 1981 to 1987 against the U.S. and vessels of other countries in the Persian Gulf and US claims of Iranian support for terrorism.[3] The sanctions were expanded in 1995 to include firms dealing with the Iranian government.[4]

The third sanctions were imposed in December 2006 pursuant to United Nations Security Council Resolution 1737 after Iran refused to comply with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1696, which demanded that Iran halt its uranium enrichment program. Initially, U.S. sanctions targeted investments in oil, gas, and petrochemicals, exports of refined petroleum products, and business dealings with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). It encompassed banking and insurance transactions (including with the Central Bank of Iran), shipping, web-hosting services for commercial endeavors, and domain name registration services.[5] Subsequent UN Resolutions have expanded sanctions against Iran.

Over the years, sanctions have taken a serious toll on Iran's economy and people. Since 1979, the United States has led international efforts to use sanctions to influence Iran's policies,[6] including Iran's uranium enrichment program, which Western governments fear is intended for developing the capability to produce nuclear weapons. Iran counters that its nuclear program is for civilian purposes, including generating electricity and medical purposes.[7]

When nuclear talks between Iran and Western governments were stalled and seen as a failure, U.S. senators cited them as a reason to enforce stronger economic sanctions on Iran.[8] On 2 April 2015, the P5+1 and Iran, meeting in Lausanne, Switzerland, reached a provisional agreement on a framework that, once finalized and implemented, would lift most of the sanctions in exchange for limits on Iran's nuclear programs extending for at least ten years.[9][10][11][12] The final agreement, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, was adopted on 18 October 2015.[13] As a result, UN sanctions were lifted on 16 January 2016.[14] On 8 May 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump announced that the United States would withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal. Sanctions by the United States were reinstated in November 2018, and expanded in 2019 and 2020 to cover Iran's financial sector. Temporary waivers were granted to some countries to continue importing reduced amounts of oil from Iran until 2019.

On 21 February 2020, Iran was placed on the FATF blacklist.[15]

The UN arms embargo on Iran expired on 18 October 2020, as agreed in Iran's 2015 nuclear deal, allowing Iran to import foreign military equipment.

Sanctions of 1979

[edit]The United States sanctions against Iran were imposed in November 1979 after radical students seized the American Embassy in Tehran and took hostages. The sanctions were imposed by Executive Order 12170, which included freezing about $8.1 billion in Iranian assets, including bank deposits, gold and other properties, and a trade embargo. The sanctions were lifted in January 1981 as part of the Algiers Accords, which was a negotiated settlement of the hostages' release.[16]

US sanctions since 1984

[edit]While the Iran–Iraq War, which began in September 1980, was in progress, in 1984, United States sanctions prohibited weapon sales and all U.S. assistance to Iran. In September 1987, following the discovery of a possible minefield in the Strait of Hormuz, Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger called for a UN arms embargo against Iran,[17] but Weinberger's call was not realized at the time.[citation needed]

In 1995, in response to the Iranian nuclear program and Iranian support of terrorist organisations, including Hezbollah, Hamas, and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, U.S. President Bill Clinton issued several executive orders with respect to Iran. Executive Order 12957 of 15 March 1995, banned U.S. investment in Iran's energy sector, and Executive Order 12959 of 6 May 1995, banned U.S. trade with and investment in Iran.

The Iran and Libya Sanctions Act (ILSA) was signed on 5 August 1996 (H.R. 3107, P.L. 104–172).[18] (ILSA was renamed in 2006 the Iran Sanctions Act (ISA) when the sanctions against Libya were terminated.[18]) On 31 July 2013, members of the United States House of Representatives voted 400 to 20 in favor of toughened sanctions.[19]

On 8 May 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump announced that the United States would withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal.[20][21] Following the U.S. withdrawal, the EU enacted an updated blocking statute on 7 August 2018 to nullify US sanctions on countries trading with Iran.[22]

The fourth set of sanctions by the United States came into effect in November 2018; the White House said that the purpose of the sanctions was not regime change, but to make Iran to change its regional policies, stop its support for regional militant groups and end its ballistic missile programme.[23] In September 2019, a U.S. official stated that the United States will sanction whoever deals with Iran or purchases its oil.[24] Also in September 2019, in response to a suspected Iranian attack on key Saudi Arabian oil facilities, Trump said that he directed the Treasury Department to "substantially increase" sanctions on Iran. The new sanctions targeted the Iranian national bank.[citation needed] A senior Trump administration official said the new sanctions targeted the financial assets of the Supreme leader's inner circle.[25] However, according to the New York Times, Tehran has disclaimed playing any part in the attacks that affected the Saudi oil facilities.[26]

On 25 August 2020, the United Nations Security Council blocked the effort of the US to re-impose snapback sanctions on Iran. The President of the UN Security Council, Indonesia's ambassador Dian Triansyah Djani, stated he is "not in a position to take further action" on US's request, citing a lack of consensus in the Security Council on the US strategy as the main reason.[27]

On 20 September 2020, the US asserted that UN sanctions against Iran were back in place, a claim that was rejected by Iran and the other remaining parties to the JCPOA.[28][29] The next day, the United States imposed sanctions on Iranian defence officials, nuclear scientists, the Atomic Energy Agency of Iran and anyone who engaged in conventional arms deals with Iran.[30] On 8 October 2020, the US imposed further sanctions on Iran's financial sector, targeting 18 Iranian banks.[31]

In February 2023, Deutsche Welle, during a report on the increase in Iran's oil exports, claimed that pressuring Iran has diplomatic costs for Washington and will ultimately lead to an increase in oil prices.[32]

UK sanctions against Iran

[edit]In July 2023, British Foreign Secretary James Cleverly announced that his government had decided to create a new sanctions regime for Iran, which will expand the United Kingdom's powers to sanction decision-makers in Tehran to include those allegedly involved in weapons proliferation.[33] This decision could be motivated a number of different factors, such as Iran recently being accepted as a full member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).[34]

UN sanctions against Iran

[edit]The UN Security Council passed a number of resolutions imposing sanctions on Iran, following the report by the International Atomic Energy Agency Board of Governors regarding Iran's non-compliance with its safeguards agreement and the Board's finding that Iran's nuclear activities raised questions within the competency of the Security Council. Sanctions were first imposed when Iran rejected the Security Council's demand that Iran suspend all enrichment-related and reprocessing activities. Sanctions will be lifted when Iran meets those demands and fulfills the requirements of the IAEA Board of Governors. Most UN sanctions were lifted on 16 January 2016, following the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1696 – passed on 31 July 2006. Demanded that Iran suspend all enrichment-related and reprocessing activities and threatened sanctions.[35]

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1737 – passed on 23 December 2006 in response to the proliferation risks presented by the Iranian nuclear program and, in this context, by Iran's continuing failure to meet the requirements of the International Atomic Energy Agency Board of Governors and to comply with the provisions of Security Council resolution 1696 (2006).[36] Made mandatory for Iran to suspend enrichment-related and reprocessing activities and cooperate with the IAEA, imposed sanctions banning the supply of nuclear-related materials and technology, and froze the assets of key individuals and companies related to the program.

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1747 – passed on 24 March 2007. Imposed an arms embargo and expanded the freeze on Iranian assets.

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1803 – passed on 3 March 2008. Extended the asset freezes and called upon states to monitor the activities of Iranian banks, inspect Iranian ships and aircraft, and to monitor the movement of individuals involved with the program through their territory.

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1835 – Passed in 2008.

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1929 – passed on 9 June 2010. Banned Iran from participating in any activities related to ballistic missiles, tightened the arms embargo, travel bans on individuals involved with the program, froze the funds and assets of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard and Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines, and recommended that states inspect Iranian cargo, prohibit the servicing of Iranian vessels involved in prohibited activities, prevent the provision of financial services used for sensitive nuclear activities, closely watch Iranian individuals and entities when dealing with them, prohibit the opening of Iranian banks on their territory and prevent Iranian banks from entering into a relationship with their banks if it might contribute to the nuclear program, and prevent financial institutions operating in their territory from opening offices and accounts in Iran.

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1984 – passed on 9 June 2011. This resolution extended the mandate of the panel of experts that supports the Iran Sanctions Committee for one year.

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 2049 – passed on 7 June 2012. Renewed the mandate of the Iran Sanctions Committee's Panel of Experts for 13 months.

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 2231 – passed on 20 July 2015. Sets out a schedule for suspending and eventually lifting UN sanctions, with provisions to reimpose UN sanctions in case of non-performance by Iran, in accordance with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.

The UN sanctions against Iran do not include oil exports from Iran.[37] As of 2019, an estimated one third of all oil traded at sea passes through the Strait of Hormuz. In August 2018, EU High Representative Mogherini, speaking at a briefing with New Zealand's Foreign Minister Winston Peters, challenged U.S. sanctions on Iran, stating that the EU are encouraging small and medium size enterprises in particular to increase business with and in Iran as part of something that is for the EU a "Security Priority".[38][39]

In September 2019, the US government announced, unilaterally, that it would begin to sanction certain Chinese entities that imported oil from Iran.[40]

On 14 August 2020, the United Nations Security Council rejected a resolution proposed by the United States to extend the global arms embargo on Iran, which was set to expire on 18 October 2020. The Dominican Republic joined the United States in voting for the resolution, short of the minimum nine "yes" votes required for adoption. Eleven members of the Security Council, including France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, abstained while Russia and China voted against the resolution.[41]

Speaking about the US desire to restore UN sanctions against Iran and extend an embargo to arms sales to the country in 2020, US Ambassador to the United Nations Kelly Craft said: "History is replete of tragedies of appeasing regimes such as this one, that for decades have kept its own people under its thumb. The Trump administration has no fear in standing in limited company on this matter, in light of the unmistakable truth guiding our actions. I only regret that other members of this [Security Council] have lost their way, and now find themselves standing in the company of terrorists."[42] She also wrote a September 20, 2020, letter to the President of the UN Security Council, pressing her point on sanctions.[43][44][45] Speaking at the US State Department in September 2020, she said: "As we have in the past, we will stand alone to protect peace and security at all times. We don't need a cheering section to validate our moral compass."[44]

Under the terms agreed in the Iran nuclear deal framework, the UN arms embargo expired on 18 October 2020, following which Iran was permitted to purchase foreign weapons and military equipment.[46] A U.S. attempt to extend UN sanctions against Iran under a JCPoA "snapback" provision was opposed by 13 Security Council members, who argued that the U.S. left the agreement with Iran in 2018.[47]

EU sanctions against Iran

[edit]EU–Iran relations have been strained in the early 2010s by the dispute over the Iranian nuclear program. The European Union along with United States have imposed sanctions against Iran over the controversies around Iranian nuclear program. These sanctions which have been described as the toughest EU sanctions imposed against any other country by European officials were last strengthened on 15 October 2012 within by the EU Council.[48][2]

On 23 January 2012, the Council of the European Union released a report in which it restated its concerns about the growth and nature of Iran's nuclear programme.[49] As a result, the council announced that it would levy an embargo on Iranian oil exports. Further, it stated that it would also freeze assets held by the Central Bank of Iran and forestall the trading of precious metals and petrochemicals to and from the country.[50] This replaces and updates the previous Council Regulation 423/2007 that was published on 27 July 2010. The new sanctions put restrictions on foreign trade, financial services, energy sectors and technologies and includes a ban on the provision of insurance and reinsurance by EU insurers to the State of Iran and Iranian owned companies.[51] Iran has since declared its intentions to close the Strait of Hormuz should the embargo be enacted.[52] At the time, the European Union accounted for 20% of Iran's oil exports, with the majority of the remaining being exported to Asian countries such as China, Japan, India, and South Korea.[53]

In response to the sanctions, Ramin Mehmanparast, representative for Iran's foreign ministry, stated that the embargo would not significantly affect Iranian oil revenues. He further said that "any country that deprives itself from Iran's energy market, will soon see that it has been replaced by others."[54]

In addition, Iran's parliament considered a law that would pre-empt the EU ban by cutting off shipments to Europe immediately, before European countries could arrange alternate supplies.[55]

On 12 April 2021, the European Union sanctioned eight Iranian militia commanders and security officials over human right abuses.[56]

In September 2023, it was announced that certain sanctions imposed by France, Germany and the UK on Iran would be retained. These sanctions were due to be lifted the following month under the JCPOA, but a decision was made to retain them in order to deter Tehran from selling drones and missiles to Russia.[57]

In May 2024, the European Union expanded the scope its sanctions regime against Iran, this time banning EU sales of components for missiles in addition to unmanned aerial vehicles, which were covered by a sanctions framework adopted in July 2023.[58]

SWIFT sanctions

[edit]On 17 March 2012, following agreement two days earlier between all 27 member states of the Council of the European Union, and the council's subsequent ruling, the SWIFT electronic banking network, the world hub of electronic financial transactions, disconnected all Iranian banks from its international network that had been identified as institutions in breach of current EU sanctions, and that further Iranian financial institutions could be disconnected from its network.[59]

Non-UN-mandated sanctions against Iran

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (January 2017) |

| Sectors | U.S. (1995– ) | E.U. (2007– ) | U.N. (2006–16) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missile/arms industry | Restricted | Restricted | Removed |

| Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps | Restricted | Restricted | Removed |

| Nuclear industry | Restricted | Restricted | Removed |

| Energy/petroleum industry | Restricted | Restricted | Removed |

| Banking | Restricted | Restricted | Removed |

| Central Bank of Iran | Restricted | Restricted | Removed |

| Shipping industry | Restricted | Restricted | Removed |

| International trade | Restricted | Restricted | Removed |

| Insurance | Restricted | Restricted | Removed |

| Foreign firms dealing with Iran | Restricted |

The European Union has imposed restrictions on cooperation with Iran in foreign trade, financial services, energy sectors and technologies, and banned the provision of insurance and reinsurance by insurers in member states to Iran and Iranian-owned companies.[51] On 23 January 2012, the EU agreed to an oil embargo on Iran, effective from July, and to freeze the assets of Iran's central bank.[61] The next month, Iran symbolically pre-empted the embargo by ceasing sales to Britain and France (both countries had already almost eliminated their reliance on Iranian oil, and Europe as a whole had nearly halved its Iranian imports), though some Iranian politicians called for an immediate sales halt to all EU states, so as to hurt countries like Greece, Spain and Italy who were yet to find alternative sources.[62][63]

On 17 March 2012, all Iranian banks identified as institutions in breach of EU sanctions were disconnected from the SWIFT, the world's hub of electronic financial transactions.[64] On 10 November 2018 Gottfried Leibbrandt, chief executive of SWIFT said in Belgium that some banks in Iran would be disconnected from this financial messaging service.[65]

One side effect of the sanctions is that the global shipping insurers based in London are unable to provide cover for items as far afield as Japanese shipments of Iranian liquefied petroleum gas to South Korea.[66]

- Beijing has tried to accommodate US concerns about Iran. It has not developed trade and investment positions there as rapidly as it might have, and has shifted some Iran-related transactional flows into Renminbi to help the Obama administration avoid sanctioning Chinese banks (similarly, India now pays for some Iranian oil imports in rupees).[67][68]

- Australia has imposed financial sanctions and travel bans on individuals and entities involved in Iran's nuclear and missile programs or assist Iran in violating sanctions, and an arms embargo.[69]

- Canada imposed a ban on dealing in the property of designated Iranian nationals, a complete arms embargo, oil-refining equipment, items that could contribute to the Iranian nuclear program, the establishment of an Iranian financial institution, branch, subsidiary, or office in Canada or a Canadian one in Iran, investment in the Iranian oil and gas sector, relationships with Iranian banks, purchasing debt from the Iranian government, or providing a ship or services to Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines, but allows the Foreign Minister to issue a permit to carry out a specified prohibited activity or transaction.[70]

- India enacted a ban on the export of all items, materials, equipment, goods, and technology that could contribute to Iran's nuclear program.[71] In 2012, the country said it was against expanding its sanctions.[72] India imports 12 percent of its oil from Iran and cannot do without it,[73] and the country planned to send a "huge delegation" to Iran in mid-March 2012 to further bilateral economic ties.[74][75] In July 2012, India has not approved the necessary insurance for Iranian ships hit by U.S. sanctions, effectively barring them from entering Indian waters.[76]

- Israel banned business with or unauthorized travel to Iran under a law banning ties with enemy states.[77] Israel has also enacted legislation that penalizes any companies that violate international sanctions.[78] Following reports of covert Israeli-Iranian trade and after the US sanctioned an Israeli company for ties with Iran, Israel imposed a series of administrative and regulatory measures to prevent Israeli companies from trading with Iran, and announced the establishment of a national directorate to implement the sanctions.[79]

- Japan imposed a ban on transactions with some Iranian banks, investments with the Iranian energy sector, and asset freezes against individuals and entities involved with Iran's nuclear program.[80] In January 2012, the second-biggest customer for Iranian oil announced it would take "concrete steps" to reduce its 10% oil dependency on Iran.[81]

- South Korea imposed sanctions on 126 Iranian individuals and companies.[82] Japan and South Korea together account for 26% of Iran's oil exports.[83]

- Switzerland banned the sale of arms and dual-use items to Iran, and of products that could be used in the Iranian oil and gas sector, financing this sector, and restrictions on financial services.[84]

- The United States has imposed an arms ban and an almost total economic embargo on Iran, which includes sanctions on companies doing business with Iran, a ban on all Iranian-origin imports, sanctions on Iranian financial institutions, and an almost total ban on selling aircraft or repair parts to Iranian aviation companies. A license from the Treasury Department is required to do business with Iran. In June 2011, the United States imposed sanctions against Iran Air and Tidewater Middle East Co. (which runs seven Iranian ports), stating that Iran Air had provided material support to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which is already subject to UN sanctions, that Tidewater Middle East is owned by the IRGC, and that both have been involved in activities including illegal weapons transportation.[85] The U.S. has also begun to designate a number of senior Iranian officials under the Iranian Human Rights Abuses Sanctions Regulations. On 14 December 2011, the U.S. Department of Treasury designated Hassan Firouzabadi and Abdollah Araqi under this sanctions program.[86] In February 2012 the US froze all property of the Central Bank of Iran and other Iranian financial institutions, as well as that of the Iranian government, within the United States.[87] The American view is that sanctions should target Iran's energy sector that provides about 80% of government revenues, and try to isolate Iran from the international financial system.[88] On 6 February 2013 the United States government blacklisted major Iranian electronics producers, Internet policing agencies, and the state broadcasting authority, in an effort to lessen restrictions of access to information for the general public. The sanctions were imposed to target the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting, which is responsible for broadcast policy in Iran and oversees the production of Iranian television and radio channels. Also targeted were the "Iranian Cyber Police" and the "Communications Regulatory Authority" which the Treasury Department describes as authorities created three years ago to filter Web sites and monitor Internet behavior while blocking Web sites deemed objectionable by the Iranian government. Currently, under American sanctions laws, any United States property held by blacklisted companies and individuals is impounded, and such companies are prohibited from engaging in any transactions with American citizens.[89] In January 2015, the U.S. Senate Banking Committee advanced "a bill that would toughen sanctions on Iran if international negotiators fail to reach an agreement on Tehran's nuclear program by the end of June."[90] On 5 November 2018, the United States government reinstated all sanctions against Iran. These sanctions had been previously lifted in accordance to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.[91] On 24 June 2019 the Trump administration announced further sanctions on Iran in response to a downing of a U.S. drone.[92]

- On 16 April 2019, a day after United States designated Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) as a Foreign Terrorist Organizations, the social media platform Instagram blocked the accounts of the IRGC, the Quds Force, its commander Qasem Soleimani, and three other IRGC commanders.[93]

- On 1 June 2023, the Biden administration imposed sanctions on Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Crops officials, who were convicted for plotting assassination abroad. The IRGC plans also targeted John Bolton and Mike Pompeo. The US sanctions targeted Mohammad Reza Ansari, an official with a unit of IRGC-Qods Force, and Hossein Hafez Amini, a dual Iranian and Turkish national, for assisting the IRGC-QF's covert operations.[94]

Reasons for sanctions

[edit]In 2012, the U.S. Department of State stated:

In response to Iran's continued illicit nuclear activities, the United States and other countries have imposed unprecedented sanctions to censure Iran and prevent its further progress in prohibited nuclear activities, as well as to persuade Tehran to address the international community's concerns about its nuclear program. Acting both through the United Nations Security Council and regional or national authorities, the United States, the member states of the European Union, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Canada, Australia, Norway, Switzerland, and others have put in place a strong, inter-locking matrix of sanctions measures relating to Iran's nuclear, missile, energy, shipping, transportation, and financial sectors. These measures are designed: (1) to block the transfer of weapons, components, technology, and dual-use items to Iran's prohibited nuclear and missile programs; (2) to target select sectors of the Iranian economy relevant to its proliferation activities; and (3) to induce Iran to engage constructively, through discussions with the United States, China, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Russia in the "E3+3 process," to fulfill its nonproliferation obligations. These nations have made clear that Iran's full compliance with its international nuclear obligations would open the door to its receiving treatment as a normal non-nuclear-weapon state under The Nonproliferation Treaty and sanctions being lifted.[95]

The website of the U.K. government states:

On 16 October 2012, the EU adopted a further set of restrictive measures against Iran as announced in Council Decision 2012/635/CFSP. These measures are targeted at Iran's nuclear and ballistic programmes and the revenues made from these programmes by the Iranian government.

In response to the deteriorating human rights situation in Iran, the EU has also adopted Council Regulation (EU) No 359/2011 of 12 April 2011. This regulation has been amended by Council Regulation (EU) No 264/2012, which includes the Annex III list of equipment that might be used for internal repression and related services (e.g. financial, technical, brokering) and internet monitoring and telecommunications equipment and related services.[96]

The BBC, in answering "Why are there sanctions?" wrote in 2015:

- Since Iran's nuclear programme became public in 2002, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has been unable to confirm Tehran's assertions that its nuclear activities are exclusively for peaceful purposes and that it has not sought to develop nuclear weapons....

- The United Nations Security Council has adopted six resolutions since 2006 requiring Iran to stop enriching uranium — which can be used for civilian purposes, but also to build nuclear bombs — and co-operate with the IAEA. Four resolutions have included progressively expansive sanctions to persuade Tehran to comply. The US and EU have imposed additional sanctions on Iranian oil exports and banks since 2012.[97]

In November 2011 the IAEA reported "serious concerns regarding possible military dimensions to Iran's nuclear programme" and indications that "some activities may still be ongoing."[98]

The United States said the sanctions were not made to topple the Iranian government, but convince it to change several of its policies.[99]

Legal challenges to the sanctions

[edit]The European Union's General Court overturned EU sanctions against two of Iran's biggest banks, Bank Saderat and Bank Mellat. The two banks had filed suit with the European court to challenge those sanctions.[citation needed]

Effects

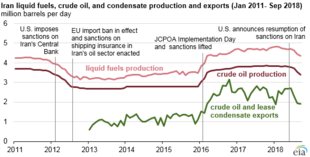

[edit]U.S. and EU leaders are trying to tighten restrictions on business with Iran, which produced 3.55 million barrels of crude a day in January, 11 percent of OPEC's total, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.[100]

The sanctions bring difficulties to Iran's $483 billion, oil-dominated economy.[61] Data published by the Iranian Central Bank show a declining trend in the share of Iranian exports from oil-products (2006–2007: 84.9%, 2007–2008: 86.5%, 2008–2009: 85.5%, 2009–2010: 79.8%, 2010–2011 (first three quarters): 78.9%).[101] The sanctions have had a substantial adverse effect on the Iranian nuclear program by making it harder to acquire specialized materials and equipment needed for the program. The social and economic effects of sanctions have also been severe,[102][103] with even those who doubt their efficacy, such as John Bolton, describing the EU sanctions, in particular, as "tough, even brutal."[104] Iranian foreign minister Ali Akhbar Salehi conceded that the sanctions are having an impact.[105] China has become Iran's largest remaining trading partner.[80]

Sanctions have reduced Iran's access to products needed for the oil and energy sectors, have prompted many oil companies to withdraw from Iran, and have also caused a decline in oil production due to reduced access to technologies needed to improve their efficiency.[citation needed]According to Undersecretary of State William J. Burns, Iran may be annually losing as much as $60 billion in energy investment.[106] Many international companies have also been reluctant to do business with Iran for fear of losing access to larger Western markets. [Naseem, M(2017) International Energy Law].As well as restricting export markets, the sanctions have reduced Iran's oil income by increasing the costs of repatriating revenues in complicated ways that sidestep the sanctions; Iranian analysts estimate the budget deficit for the 2011–2012 fiscal year, which in Iran ends in late March, at between $30bn to $50bn.[107] The effects of U.S. sanctions include expensive basic goods for Iranian citizens, and an aging and increasingly unsafe civil aircraft fleet. According to the Arms Control Association, the international arms embargo against Iran is slowly reducing Iran's military capabilities, largely due to its dependence on Russian and Chinese military assistance. The only substitute is to find compensatory measures requiring more time and money, and which are less effective.[108][109] According to at least one analyst (Fareed Zakaria), the market for imports in Iran is dominated by state enterprises and state-friendly enterprises, because the way to get around the sanctions is smuggling, and smuggling requires strong connections with the government. This has weakened Iranian civil society and strengthened the state.[citation needed]

The value of the Iranian rial has plunged since autumn 2011, it is reported to have devalued up to 80%, falling 10% immediately after the imposition of the EU oil embargo[110] since early October 2012,[111] causing widespread panic among the Iranian public.[107] In January 2012, the country raised the interest rate on bank deposits by up to 6 percentage points in order to curtail the rial's depreciation. The rate increase was a setback for Ahmadinejad, who had been using below-inflation rates to provide cheap loans to the poor, though naturally Iranian bankers were delighted by the increase.[107] Not long after, and just a few days after Iran's economic minister declared that "there was no economic justification" for devaluing the currency because Iran's foreign exchange reserves were "not only good, but the extra oil revenues are unprecedented,"[107] the country announced its intention to devalue by about 8.5 percent against the U.S. dollar, set a new exchange rate and vowed to reduce the black market's influence (presumably booming because of the lack of confidence in the rial).[112] The Iranian Central Bank desperately tried to keep the value of the rial afloat in the midst of the late 2012 decline by pumping petrodollars into the system to allow the rial to compete against the US dollar.[113] Efforts to control inflation rates were set forth by the government through a three-tiered-multiple-exchange-rate;[114] this effect has failed to prevent the rise in cost of basic goods, simultaneously adding to the public's reliance on the Iranian black-market exchange rate network.[113] Government officials attempted to stifle the black-market by offering rates 2% below the alleged black-market rates, but demand seems to be outweighing their efforts.[115][116]

Sanctions tightened further when major supertanker companies said they would stop loading Iranian cargo. Prior attempts to reduce Iran's oil income failed because many vessels are often managed by companies outside the United States and the EU; however, EU actions in January extended the ban to ship insurance. This insurance ban will affect 95 percent of the tanker fleet because their insurance falls under rules governed by European law. "It's the insurance that's completed the ban on trading with Iran," commented one veteran shipbroker.[117] This completion of the trading ban left Iran struggling to find a buyer for nearly a quarter of its annual oil exports.[62]

Another effect of the sanctions, in the form of Iran's retaliatory threat to close the Strait of Hormuz, has led to Iraqi plans to open export routes for its crude via Syria, though Iraq's deputy prime minister for energy affairs doubted Iran would ever attempt a closure.[117]

After Iranian banks blacklisted by the EU were disconnected from the SWIFT banking network, then Israeli Finance Minister Yuval Steinitz stated that Iran would now find it more difficult to export oil and import products. According to Steinitz, Iran would be forced to accept only cash or gold, which is impossible when dealing with billions of dollars. Steinitz told the Israeli cabinet that Iran's economy might collapse as a result.[118][119]

The effects of the sanctions are usually denied in the Iranian press.[120][121] Iran has also taken measures to circumvent sanctions, notably by using front countries or companies and by using barter trade.[122] At other times the Iranian government has advocated a "resistance economy" in response to sanctions, such as using more oil internally as export markets dry up and import substitution industrialization of Iran.[123][124] However, based on research, the sanctions resulted in welfare losses across all income groups in Iran, with wealthier groups suffering greater losses compared to poorer groups.[125][126] Additionally, income concentration and share within top income groups declined post-sanctions.[127]

In October 2012, Iran began struggling to halt a decline in oil exports which could plummet further due to international sanctions, and the International Energy Agency estimated that Iranian exports fell to a record of 860,000 bpd in September 2012 from 2.2 million bpd at the end of 2011. The results of this fall led to a drop in revenues and clashes on the streets of Tehran when the local currency, the rial, collapsed. The output in September 2012 was Iran's lowest since 1988.[128]

Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman Ramin Mehmanparast has said that the sanctions were not just aimed at Iran's nuclear program and would continue even if the nuclear dispute was resolved.[129]

In 2018, as a response to US visa restrictions for those who have visited Iran after 2011, Iran ceased affixing visas in passports and stamping passports on entry of foreigners from most countries.[130][131][132]

"Resistance economy"

[edit]In the face of increased economic pressure from the United States and Europe and a marked decrease of oil exports,[2] Iran has sought to manage the impact of international sanctions and limit capital outflows by seeking to build a "resistance economy,"[133][134] replacing imports with domestic goods and banning luxury imports such as computers and mobile phones.[135] This is predicted to lead to an increase in smuggling, as "people will find a way to smuggle in what the Iranian consumer wants."[136] In 2012, Iran attempted to sell more crude to Chinese and Indian refiners, but China—the single-largest buyer of Iranian crude—has been curtailing its oil imports from Iran down to half their former level.[62]

On 20 October 2018 Association of German Banks stated that exports from Germany to Iran dropped 4% to 1.8 billion Euros since January.[137]

Iran has intensified industrial cooperation with the Russian Federation to support its petrochemical industry, despite sanctions. Iran increased the import of Russian natural gas through Azerbaijan, and is expanding the pipeline to Pakistan and Oman. In July 2022, Iran and Gazprom signed a memorandum of understanding worth US$40bn, supporting the development of the Kish Gas Field, and the North Pars Gas Field.[138]

In September 2022, after re-negotiations of the JCPOA were stalling, Iran increased its oil exports to China with favorable prices, circumventing economic sanctions.[139] Later that month, the U.S. imposed secondary sanctions on two Chinese entities, and an Indian petrochemical company that traded with Iranian oil.[140]

Since the U.S. and European countries reinstated or increased sanctions against Iran, the country has greatly increased its self-sufficiency particularly in the agricultural, food and pharmaceutical sectors. It is now a main exporter of dairy products to the UAE and Azerbaijan. In the pharmaceutical sector, Iran continues to rely on India and China for starting materials, but produced 97% of all used drugs domestically. Many chemical ingredients are derived from petrochemicals, and are easily obtained by its domestic economy.[141]

The comprehensive economic sanctions in place against Iran had a major effect on the consolidation of certain industries. Because longterm sanctions are difficult to remove, they no longer motivate the Iranian leadership to change direction. Furthermore, the sanctions have led to a consolidation of power, as smaller independent companies find it more difficult to evade sanctions. Due to the expansion of government-owned companies in Iran, more money has flowed to government and military coffers.[142]

Political effects

[edit]In 2012, 94 Iranian Parliamentarians signed a formal request to have Ahmadinejad appear before the Majles (parliament) to answer questions about the currency crisis. The Supreme Leader terminated the parliament's request in order to unify the government in the face of international pressure.[143] Nonetheless, Ahmadinejad has been called to questioning by parliament on a number of occasions, to justify his position on issues concerning domestic politics. His ideologies seem to have alienated a large portion of the parliament, and stand in contrast to the standpoint of the Supreme Leader.[dubious – discuss][144][145]

A report by Dr. Kenneth Katzman, for the Congressional Research Service, listed the following factors as major examples of economic mismanagement on the part of the Iranian government:

- The EU oil embargo and the restrictions on transactions with Iran's Central Bank have dramatically reduced Iran's oil sales – a fact acknowledged by Oil Minister Rostam Qasemi to the Majles on 7 January 2013. He indicated sales had fallen 40% from the average of 2.5 million barrels per day (mbd) in 2011 (see chart above on Iran oil buyers). This is close to the estimates of energy analysts, which put Iran's sales at the end of 2012 in a range of 1 mbd to 1.5 mbd. Reducing Iran's sales further might depend on whether U.S. officials are able to persuade China, in particular, to further cut buys from Iran—and to sustain those cuts.

- Iran has been storing some unsold oil on tankers in the Persian Gulf, and it is building new storage tanks onshore. Iran has stored excess oil (21 million barrels, according to Citigroup Global Markets) to try to keep production levels up—shutting down wells risks harming them and it is costly and time-consuming to resume production at a well that has been shut. However, since July 2012, Iran reportedly has been forced to shut down some wells, and overall oil production has fallen to about 2.6 million barrels per day from the level of nearly 4.0 mbd at the end of 2011.

- The oil sales losses Iran is experiencing are likely to produce over $50 billion in hard currency revenue losses in a one-year period at current oil prices. The IMF estimated Iran's hard currency reserves to be $106 billion as of the end of 2011, and some economists say that figure may have fallen to about $80 billion as of November 2012. Analysts at one outside group, the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, believe Iran's hard currency reserves might be exhausted entirely by July 2014 at current rates of depletion. Compounding the loss of oil sales by volume is that many of its oil transactions reportedly are now conducted on a barter basis—or in exchange for gold, which is hard currency but harder to use than cash is. In addition, the 6 February 2013, the imposition of sanctions on Iran's ability to repatriate hard currency could cause the depletion rate to increase.

- On 15 October 2012, Iran said that to try to stretch its hard currency reserve, it would not supply hard currency for purchases of luxury goods such as cars or cellphones (the last 2 of the government's 10 categories of imports, ranked by their importance). The government is still supplying hard currency for essential and other key imports. Importers for essential goods can obtain dollars at the official rate of 12,260 to the dollar, and importers of other key categories of goods can obtain dollars at a new rate of 28,500 to the dollar. The government has also threatened to arrest the unofficial currency traders who sell dollars at less than the rate of about 28,500 to the dollar. The few unofficial traders that remain active are said to be trading at approximately that rate so as not to risk arrest.

- Some Iranians and outside economists worry that hyperinflation might result. The Iranian Central Bank estimated on 9 January 2013 that the inflation rate is about 27%—the highest rate ever acknowledged by the bank—but many economists believe the actual rate is between 50% and 70%.[citation needed] This has caused Iranian merchants to withhold goods or shut down entirely because they are unable to set accurate prices. Almost all Iranian factories depend on imports and the currency collapse has made it difficult for Iranian manufacturing to operate.

- Beyond the issue of the cost of imported goods, the Treasury Department's designations of affiliates and ships belong to Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL) reportedly are harming Iran's ability to ship goods at all, and have further raised the prices of goods to Iranian import-export dealers. Some ships have been impounded by various countries for nonpayment of debts due on them.

- Suggesting Iran's operating budget is already struggling; some reports say the government has fallen behind in its payments to military personnel and other government workers. Others say the government has begun "means testing" in order to reduce social spending payments to some of the less needy families. In late 2012, it also postponed phase two of an effort to wean the population off subsidies, in exchange for cash payments of about $40 per month to 60 million Iranians. Phase one of that program began in December 2010 after several years of debate and delay, and was praised for rationalizing gasoline prices.[clarification needed] Gasoline prices now run on a tiered system in which a small increment is available at the subsidized price of about $1.60 per gallon, but amounts above that threshold are available only at a price of about $2.60 per gallon, close to the world price. Before the subsidy phase-out, gasoline was sold for about 40 cents per gallon.

- Press reports indicate that sanctions have caused Iran's production of automobiles to fall by about 40% from 2011 levels. Iran produces cars for the domestic market, such as the Khodro, based on licenses from European automakers such as Renault and Peugeot. The currency collapse has largely overtaken the findings of an IMF forecast, released in October 2012, which Iran would return to economic growth in 2013, after a small decline in 2012. An Economist Intelligence Unit assessment published in late 2012 indicates Iran's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) likely contracted about 3% in 2012 and will contract an additional 1.2% in 2013. ("Oil Sanctions on Iran: Cracking Under Pressure.")

- Mitigating some of the effects are that some private funds are going into the Tehran Stock Exchange and hard assets, such as property. However, this trend generally benefits the urban elite.[146]

In late September 2022, when violent unrest erupted in major Iranian cities due to the death of a 22-year-old Kurdish woman in police custody, Iranians had reported of harsh economic conditions due to sanctions, which in part were blamed for the public discontent.[147] Subsequent to the deadly crack-down by Iranian authorities, America and Europe had announced additional sanctions, while partly lifting limitations on communication technologies with Iran. But according to an analysis by Iranian exiles, Trump's "maximum pressure sanctions" had only exacerbated constraints on civil liberties in Iran, and likely contributed to the election of the "hardliner" Ebrahim Raisi. The International Crisis Group warned that efforts to "deepen Iran's domestic fault lines" were likely to cause the political élite in Iran to "close ranks and bring down the iron fist." Some Western analysts also point out that a weaker Iranian currency makes it harder for struggling citizens to purchase imported goods, disproportionally affecting women and ethnic minorities.[148]

In September 2022, the IMF also concluded in a working paper, "coupled with low economic growth and high unemployment, rising inflation has fueled widespread protests in the country amid a significant erosion in purchasing power." According to an estimate by Iran's Ministry of Labour and Social Services, the web of sanctions has pushed one-third of Iranians into poverty. Conservative Iranian analyst Abdolreza Davari confirmed that economic despair is one of the major factors uniting those who are opposed to the Ebrahim Raisi-led government. The protests themselves were seen as a possible stumbling block to revive re-negotiations for the JCPOA, as more sanctions were imposed on Iranian officials.[149]

Effect on oil price

[edit]According to the U.S., Iran could reduce the world price of crude petroleum by 10%, saving the United States annually $76 billion (at the proximate 2008 world oil price of $100/bbl). Opening Iran's market place to foreign investment could also be a boon to competitive U.S. multinational firms operating in a variety of manufacturing and service sectors.[150]

In September 2018, Iranian oil minister Bijan Zanganeh warned U.S. President Donald Trump to stop interfering in the Middle East if he wants the oil prices to stop increasing. Zanganeh said, "If he (Trump) wants the price of oil not to go up and the market not to get destabilized, he should stop unwarranted and disruptive interference in the Middle East and not be an obstacle to the production and export of Iran's oil."[151]

In October 2021, Iranian oil minister Javad Owji said if U.S.-led sanctions on Iran's oil and gas industry are lifted, Iran will have every capability to tackle the 2021 global energy crisis.[152]

With economic sanctions in place against Iran, energy analysts expect a tight petroleum market well into 2023. In contrast to the United States, European countries would like to see a return of Iran (and Venezuela) to the global oil market to ease inflationary pressures worldwide.[153]

Impact on regional economies

[edit]Iran relies on regional economies for conducting private as well as state-sponsored business. In 2018, after the U.S. re-imposed secondary sanctions, the trade relations with neighboring countries, such as Afghanistan and Iraq, which had increased significantly prior to 2016, took a significant hit.[154] In November 2019, when financial sanctions were further tightened by the Trump administration and the Rial devaluation continued, a subsequent increase in energy prices caused widespread protests and violent confrontations in Tehran and other major cities. The economies of border regions with urban areas, such as Zahedan, felt the most drastic impact as traders had to pay more for imports, e.g. electronic appliances, while at the same time, the export value for manufactured goods, such as Persian rugs, decreased.[155] Iraq's economy was also seriously affected by the continued financial sanctions since Iran is a major exporter of wheat to Iraq, and food prices increased in Iraq after 2016.[156]

In early May 2020, with the parliamentary election of a new Iraqi prime minister, the U.S. extended Iraq's sanction waiver for the import of refined Iranian fuels and electricity from 30 days to 4 months in order to increase the political and economic stability in the region.[157]

According to the United Nations Special Rapporteur Idriss Jazairy, the reimposition of economic sanctions after the unilateral US withdrawal in 2018 "is destroying the economy and currency of Iran, driving millions of people into poverty and making imported goods unaffordable." He appealed to the United States and the European Union to ensure that Iranian financial institutions are able to perform payments for essential goods, including foods, medicines and industrial imports. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights stressed that "sanctions must not harm the human rights of ordinary citizens."[158]

Humanitarian impact

[edit]Pharmaceuticals and medical equipment do not fall under international sanctions, but Iran is facing shortages of drugs for the treatment of 30 illnesses—including cancer, heart and breathing problems, thalassemia and multiple sclerosis (MS)—because it is not allowed to use international payment systems.[159] A teenage boy died from haemophilia because of a shortage of medicine caused by the sanctions.[160] Deliveries of some agricultural products to Iran have also been affected for the same reasons.[161]

Drug imports to Iran from the U.S. and Europe decreased by approximately 30 percent in 2012, according to a report by the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.[162] In 2013, The Guardian reported that some 85,000 cancer patients required forms of chemotherapy and radiotherapy that had become scarce. Western governments had built waivers into the sanctions regime to ensure that essential medicines could get through, but those waivers conflicted with blanket restrictions on banking, as well as bans on "dual-use" chemicals that might have a military as well as a medical application. An estimated 40,000 haemophiliacs could not get blood-clotting medicines, and operations on haemophiliacs were virtually suspended because of the risks created by the shortages. An estimated 23,000 Iranians with HIV/AIDS had severely restricted access to the drugs they need. The society representing the 8,000 Iranians suffering from thalassemia, an inherited blood disorder, said its members were beginning to die because of a lack of an essential drug, deferoxamine, used to control the iron content in the blood. Further, Iran could no longer buy medical equipment such as autoclaves, essential for the production of many drugs, because some of the biggest Western pharmaceutical companies refused to do business with the country.[163]

Journalists reported on the development of a black market for medicine.[164] Though vital drugs were not affected directly by the sanctions, the amount of hard currency available to the ministry of health was severely limited. Marzieh Vahid-Dastjerdi, Iran's first female government minister since the Iranian Revolution, was dismissed in December 2012 for speaking out against the lack of support from the government in times of economic hardship.[165] Furthermore, Iranian patients were at risk of amplified side effects and reduced effectiveness because Iran was forced to import medicines, and chemical building blocks for other medicines, from India and China, as opposed to obtaining higher-quality products from Western manufacturers. Because of patent protections, substitutions for advanced medicines were often unattainable, particularly when it came to diseases such as cancer and multiple sclerosis.[166]

China, the UK, the Group of 77 and experts are pressing the US to ease sanctions on Iran to help it fight the growing coronavirus outbreak.[167] "There is no doubt that Iran's capacity to respond to the novel coronavirus has been hampered by the Trump administration's economic sanctions, and the death toll is likely much higher than it would have been as a result," Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) Co-director Mark Weisbrot said. "There can also be no question that the sanctions have affected Iran's ability to contain the outbreak, leading in turn to more infections, and possibly to the virus's spread beyond Iran's borders."[168]

On 6 April 2020, Human Rights Watch released a report urging the United States to ease sanctions on Iran "to ensure Iran access to essential humanitarian resources during the [coronavirus] pandemic."[169] The impact of sanctions on Iran made the COVID-19 management a difficult issue in Iran. While enduring crippling sanctions, the healthcare system fought COVID-19 with a low budget and inadequately equipped facilities. [170][171]

In October 2020, Bloomberg reported that US sanctions had halted a flu vaccine shipment of 2 million doses. Iran's Red Crescent Society indicated how the drastic financial sanctions rendered the community Shahr Bank insolvent, which halted the crucial shipment.[172]

Civil movement against sanctions

[edit]The "Civil Movement" was initiated by two prominent Iranian economists—Dr. Mousa Ghaninejad, of Tehran's Petroleum University of Technology, and Dr. Mohammad Mehdi Behkish, of Tehran's Allameh Tabatabaei University—on 14 July 2013. They described the sanctions as an "unfair" and "illogical" tool, arguing that a freer economy would lead to less political enmity and encourage amicable relationships between countries. They also noted that sanctions against one country punish not only the people of that country, but also the people of its trade partners.[173]

The movement was supported by a large group of intellectuals, academics, civil society activists, human rights activists and artists.[173][174][175] In September 2013, the International Chamber of Commerce-Iran posted an open letter by 157 Iranian economists, lawyers and journalists criticizing the humanitarian consequences of sanctions and calling on their colleagues across the world to pressure their governments to take steps to resolve the underlying conflict.[176]

In April 2021, more than 40 grassroots organisations have called on US President Joe Biden's administration to lift restrictions that "have obstructed the flow of critical vaccines, medicine and humanitarian goods into Iran". Iran had struggled to acquire Western vaccines due to sanctions, and was one of the worst hit countries by the Covid-19 pandemic.[177]

Frozen assets

[edit]After the Iranian Revolution in 1979, the United States ended its economic and diplomatic ties with Iran, banned Iranian oil imports and froze approximately 11 billion 1980-US dollars of its assets.[178]

In the years of 2008 to 2013, billions of dollars of Iranian assets abroad were seized or frozen, including a building in New York City,[179] and bank accounts in Great Britain, Luxembourg,[180] Japan[181] and Canada.[182]

In 2012, Iran reported that the assets of Guard-linked companies in several countries were frozen but in some cases the assets were returned.[183]

The chairman of the Majlis Planning and Budget Committee says $100 billion of Iran's money was frozen in foreign banks because of the sanctions imposed on the country.[184] In 2013, only $30 billion to $50 billion of its foreign exchange reserves (i.e. roughly 50% of total) was accessible because of sanctions.[185]

Sanctions relief

[edit]When the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action between Iran and the P5+1 was implemented in early 2016, sanctions relief affected the economy of Iran in four principal ways:[186]

- Release of Iran's frozen funds abroad, estimated at $29 billion, representing approximately one third of Iran's foreign held reserves.[187]

- The removal of sanctions against exports of Iranian oil.

- Allow foreign firms to invest in Iran's oil and gas, automobiles, hotels and other sectors.

- Allow Iran to trade with the rest of the world and use the global banking system such as SWIFT.

According to the Central Bank of Iran, Iran would use funds unfrozen by its nuclear deal mainly to finance domestic investments, keeping the money abroad until it was needed.[188]

According to the Washington Institute in 2015: "The pre-deal asset freeze did not have as great an impact on the Iranian government as some statements from Washington suggested. And going forward, the post-deal relaxation of restrictions will not have as great an impact as some critics of the deal suggest."[189]

On 16 January 2016, the International Atomic Energy Agency said that Iran had adequately restricted its nuclear program, resulting in the United Nations lifting some of the sanctions.[190][191][192]

In February 2019, France, Germany and the United Kingdom announced that they have created a payment channel named INSTEX to bypass the newly reimposed sanctions by the United States, following the unilateral withdrawal from the JCPOA by the Trump administration.[193] The Trump administration warned that countries engaging in financial transactions with Iran could face secondary U.S. sanctions.[194]

In late January 2020, the Swiss Humanitarian Trade Arrangement (SHTA) with Iran was implemented, assuring export guarantees through Swiss financial institutions for shipments of food and medical products to the Islamic republic. Geneva-based bank BCP and a large Swiss drugmaker were participating in the initial pilot shipment of essential medicines worth 2.3 million euros ($2.55 million).[195]

According to one independent study in 2022, Iran could see a windfall of one trillion US dollars over 10 years if a new agreement is signed with the P5+1.[196]

See also

[edit]- Foreign relations of Iran

- Iran–Contra affair

- Nuclear program of Iran

- List of parties to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

- Resistance economy

- United States embargoes

- International sanctions during the Venezuelan crisis

- International sanctions during apartheid

- Sanctions against Iraq

- Sanctions against Japan

- Sanctions against North Korea

- International sanctions during the Russo-Ukrainian War

- List of people and organizations sanctioned in relation to human rights violations in Belarus

References

[edit]- ^ "Russia is Now the World's Most-Sanctioned Nation". Bloomberg.com. 7 March 2022. Archived from the original on 30 August 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Haidar, J.I., 2017."Sanctions and Exports Deflection: Evidence from Iran Archived 28 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine," Economic Policy (Oxford University Press), April 2017, Vol. 32(90), pp. 319-355.

- ^ Levs, Josh (23 January 2012). "A summary of sanctions against Iran". CNN. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Zirulnick, Ariel (24 February 2011). "Sanction Qaddafi? How 5 nations have reacted to sanctions: Iran". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "31 CFR 560.540 – Exportation of certain services and software incident to Internet-based communications". Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School. United States Statutes at Large. 10 March 2010. Archived from the original on 6 May 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ Younis, Mohamed (7 February 2013). "Iranians Feel Bite of Sanctions, Blame U.S., Not Own Leaders". Gallup World. Gallup. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ Nichols, Michelle & Charbonneau, Louis (5 October 2012). "U.N. chief says sanctions on Iran affecting its people". Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ Lakshmanan, Indira A.R. (9 April 2013). "U.S. Senators Seeking Tougher Economic Sanctions on Iran". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 30 August 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ "Iranian nuclear deal: Mixed reaction greets tentative agreement". CBC. 3 April 2015. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ Charbonneau, Louis & Nebehay, Stephanie (2 April 2015). "Iran, world powers reach initial deal on reining in Tehran's nuclear program". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ "Iran nuclear talks: 'Framework' deal agreed". BBC News. 3 April 2015. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ Labott, Elise; Castillo, Mariano; Shoichet, Catherine E. (2 April 2015). "Iran nuclear deal framework announced". CNN. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ "EU officially announces October 18 adoption day of JCPOA". Islamic Republic News Agency. 18 October 2015. Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ "UN chief welcomes implementation day under JCPOA". Islamic Republic News Agency. 17 January 2016. Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ "Iran blacklisted by 200 member nations of Financial Action Task Force". The Jerusalem Post. 22 February 2020. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ Charles Nelson Brower, Jason D. Brueschke, The Iran-United States Claims Tribunal (1998) p. 7 online Archived 25 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1987/09/29/possible-new-minefield-found-in-persian-gulf/75e2b674-3652-423a-9ece-2ec107c49a88/.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Katzman, Kenneth (13 June 2013). "Iran Sanctions" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ "Tehran is changing, pity about DC". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 9 August 2013. Archived from the original on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ^ Landler, Mark (8 May 2018). "Trump Announces U.S. Will Withdraw From Iran Nuclear Deal". MSN. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ Landler, Mark (8 May 2018). "Trump Withdraws U.S. From 'One-Sided' Iran Nuclear Deal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ "Updated Blocking Statute in support of Iran nuclear deal enters into force". Europa.eu. European Commission Press Release Database. 6 August 2018. Archived from the original on 7 August 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ "US targets arms program with strongest sanctions since scrapping Iran deal". ABC News. 3 November 2018. Archived from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ "U.S. will sanction whoever purchases Iran's oil: official". Reuters. 8 September 2019. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ^ "US puts new sanctions on Iranian supreme leader's inner circle". Archived from the original on 19 November 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- ^ Sullivan, Eileen (20 September 2019). "Trump Announces New Sanctions on Iran". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- ^ hermesauto (26 August 2020). "UN blocks US bid to trigger 'snapback' sanctions on Iran". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 17 December 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Motamedi, Maziar. "US claims UN sanctions on Iran reinstated. The world disagrees". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Jennifer Hansler (20 September 2020). "US has reimposed UN sanctions on Iran, Pompeo says". CNN. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick. "US announces new Iran sanctions and claims it is enforcing UN arms embargo". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 February 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "US hits Iran's financial sector with fresh round of sanctions". 8 October 2020. Archived from the original on 17 December 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ "How Iran is boosting oil exports despite US sanctions". Deutsche Welle. 1 February 2023. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ "Britain to target Iranian decision makers with new sanctions regime". Reuters. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ "Iran joins Shanghai Cooperation Organisation". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 11 August 2023. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ "Security Council demands Iran suspend uranium enrichment by 31 August, or face possible economic, diplomatic sanctions". United Nations. 31 July 2006. Archived from the original on 16 August 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ "UN Sanctions". Department of foreign affairs and Trade. Australia. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ Leigh, Karen (29 May 2019). "Hong Kong Rejects U.S. Warning on Ship Breaching Iran Sanctions". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "Council of EU - Newsroom". newsroom.consilium.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ Mitnick, Joshua (19 June 2014). "U.S. Treasury Secretary Reassures Israel on Iran Sanctions". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "U.S. to sanction Chinese entities over Iranian oil: Pompeo". Reuters. Reuters. 25 September 2019. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ "'Bullying will fail': US loses bid to extend Iran arms embargo". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ Gladstone, Rick (25 August 2020). "Security Council Leader Rejects U.S. Demand for U.N. Sanctions on Iran; The setback elicited an angry reaction from the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, who accused her counterparts of standing with terrorists". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Barada, Ali [@BaradaAli] (21 September 2020). "#BreakingNews @USUN @USAmbUN letter to #UN Security President @Niger_ONU demanding "all Member States" to "implement the re-imposed measures" on #Iran, including nuclear, ballistic missile related, arms embargo & other targeted sanctions on individuals & entities... https://t.co/oBTcYl1gev" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ a b Jakes, Lara; Sanger, David E.; Fassihi, Farnaz (21 September 2020). "Trying to Hammer Iran With U.N. Sanctions, U.S. Issues More of Its Own". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Schwirtz, Michael (14 August 2020). "U.N. Security Council Rejects U.S. Proposal to Extend Arms Embargo on Iran". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Iran says UN arms embargo lifted, allowing it to buy weapons". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "Iran sanctions: nearly all UN security council unites against 'unpleasant' US". The Guardian. 21 August 2020.

- ^ "EU imposes new sanctions on Iran". BBC. 15 October 2012. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "Council conclusions on Iran" (PDF). Council of the European Union. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ "New European Union sanctions target Iran nuclear program". CNN. 23 January 2012. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ a b Akbar E. Torbat, EU Embargoes Iran over the Nuke Issue, 8 July 2012, http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/article31795.htm Archived 12 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Iran Raises Stakes in U.S. Showdown With Threat to Close Hormuz". Bloomberg.com. 22 April 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ Marcus, Jonathan (23 January 2012). "What will be the impact of the EU ban on Iranian oil?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "Iran defiant as EU imposes oil embargo". Al Jazeera. 24 January 2012. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "Germany urges restraint after Iran oil stop threat". Times of Oman. Agence France-Presse. 29 January 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ^ "EU sanctions Iran over human rights abuses for first time since 2013". Yahoo. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "UK, France and Germany to keep nuclear sanctions on Iran". BBC News. 15 September 2023. Archived from the original on 15 September 2023. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- ^ "Iran: Council broadens EU restrictive measures in view of Iran military support of Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine and armed groups in the Middle East and Red Sea region". Council of the European Union. 14 May 2024. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "SWIFT News & Events". SWIFT - The global provider of secure financial messaging services. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Solomon, Jay (26 June 2015). "Shift Clouds Iran Nuclear Deal". Wall Street Journal: A9.

- ^ a b Nasseri, Ladane (12 February 2012). "Iran Won't Yield to Pressure, Foreign Minister Says; Nuclear News Awaited". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ a b c Blas, Javier; Bozorgmehr, Najmeh (20 February 2012). "Iran struggles to find new oil customers". The Financial times. Archived from the original on 21 February 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ "Iran stops oil sales to British, French companies". Reuters. 19 February 2012. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

Iran's top oil buyers in Europe were making substantial cuts in supply months in advance of European Union sanctions, reducing flows to the continent . . . by more than a third—or over 300,000 barrels daily. . . . Iran was supplying more than 700,000 barrels per day to the EU plus Turkey in 2011, industry sources said.

- ^ "Iranian banks reconnected to SWIFT network after four-year hiatus". Reuters. 17 February 2016. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ "SWIFT system to disconnect some Iranian banks this weekend". Arab News. 9 November 2018. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ "EU sanctions bring Iran's LPG exports to near halt". Reuters. 31 October 2012. Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ "New sanctions on Iran constrict trade flows to Asia". Reuters. 7 February 2012. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ "Iran And China Macgyver A Way Around US Sanctions". The American Interest. 9 May 2012. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ^ Government of Australia, Australia's autonomous sanctions: Iran Archived 30 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 29 July 2010

- ^ Government of Canada, Sanctions against Iran Archived 16 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 26 July 2010

- ^ "India imposes more sanctions on Iran". The Hindu. 1 April 2011. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Dikshit, Sandeep (11 February 2012). "India against more sanctions on Iran". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "India won't cut Iranian oil imports despite US, EU sanctions: Pranab Mukherjee". The Times of India. Reuters. 30 January 2012. Archived from the original on 2 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "Govt wants more exports to Iran". The Times of India. TNN. 10 February 2012. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "Payment issue with Iran resolved: FIEO". The Economic Times. 2 March 2012. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ Mehdudia, Sujay (27 July 2012). "India bans U.S.-sanctioned Iranian ships from its waters". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Somfalvi, Attila (30 May 2011). "PM clarifies: Ties with Iran forbidden". Yedioth Ahronoth. Archived from the original on 2 June 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ France 24, "Israel to 'finally' impose sanctions on Iran", 3 March 2011

- ^ Keinon, Herb (26 June 2011). "Gov't expands economic sanctions against Iran". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 1 July 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Japan imposes new Iran sanctions over nuclear programme". BBC News. 3 September 2010. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "Q&A: Iran sanctions". BBC News. 6 February 2012. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Sang-Hun, Choe (8 September 2010). "South Korea Aims Sanctions at Iran". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 June 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ "Japan 'to reduce Iran oil imports'". BBC News. 12 January 2012. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Reid, Katie (19 January 2011). "Switzerland brings Iran sanctions in line with EU". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ Dombey, Daniel (24 June 2011). "US widens scope of Iran sanctions". The Financial Times. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ OFAC Targets Two Iranians for SDN Designations, Sanction Law, 14 December 2011

- ^ Calmes, Jackie; Gladstone, Rick (6 February 2012). "Obama Imposes Freeze on Iran Property in U.S." The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Katzman, Kenneth (3 February 2011). "Summary" (PDF). Iran Sanctions. Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Gladstone, Rick (6 February 2013). "United States Announces New Iran Sanctions". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ Zengerle, Patricia. "Senate panel advances Iran sanctions bill." Archived 31 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine Jewish Journal. 29 January 2015. 29 January 2015.

- ^ Borak, Donna; Gaouette, Nicole (5 November 2018). "US officially reimposes all sanctions lifted under 2015 Iran nuclear deal". CNN. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ "Trump's new Iran sanctions may have modest effect". Los Angeles Times. 24 June 2019. Archived from the original on 25 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ "Instagram Blocks Guards', Soleimani's Pages". RFE/RL. 16 April 2019. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ Hansler, Jennifer (1 June 2023). "US sanctions Iranian officials accused of plotting assassinations abroad including against Bolton and Pompeo". CNN. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ "Iran Sanctions". Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "Embargoes and sanctions on Iran". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ "What are the sanctions on Iran?". BBC News. 30 March 2015. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.