Same-sex marriage

| Part of the LGBTQ rights series |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ topics |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

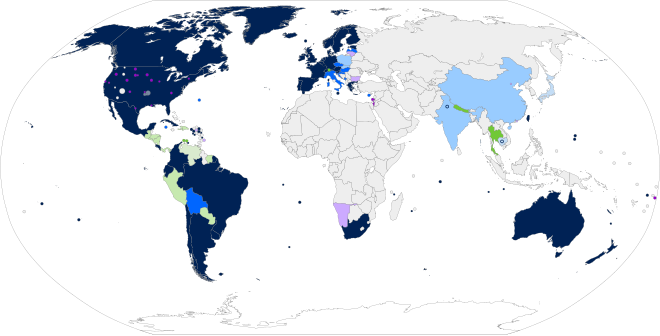

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same legal sex. As of 2025,[update] marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 37 countries, with a total population of 1.5 billion people (20% of the world's population). The most recent jurisdiction to legalize same-sex marriage is Liechtenstein. Thailand is set to begin performing same-sex marriages in January 2025.

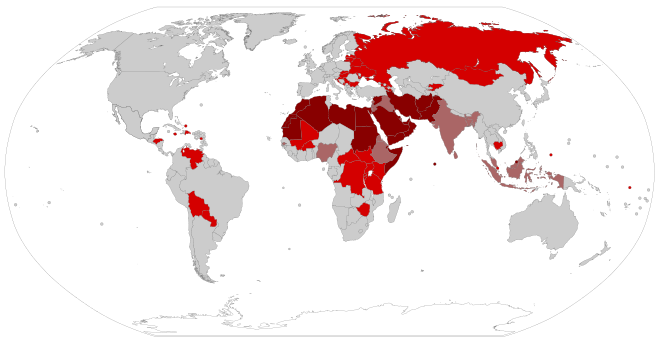

Same-sex marriage is legally recognized in a large majority of the world's developed countries; notable exceptions are Italy, Japan, South Korea and the Czech Republic. Adoption rights are not necessarily covered, though most states with same-sex marriage allow those couples to jointly adopt as other married couples can. Some countries, such as Nigeria and Russia, restrict advocacy for same-sex marriage.[1] A few of these are among the 35 countries (as of 2023) that constitutionally define marriage to prevent marriage between couples of the same sex, with most of those provisions enacted in recent decades as a preventative measure. Other countries have constitutionally mandated Islamic law, which is generally interpreted as prohibiting marriage between same-sex couples.[citation needed] In six of the former and most of the latter, homosexuality itself is criminalized.

There are records of marriage between men dating back to the first century.[2] Michael McConnell and Jack Baker[3][4] are the first same sex couple in modern recorded history[5] known to obtain a marriage license,[6] have their marriage solemnized, which occurred on September 3, 1971, in Minnesota,[7] and have it legally recognized by any form of government.[8][9] The first law providing for marriage equality between same-sex and opposite-sex couples was passed in the continental Netherlands in 2000 and took effect on 1 April 2001.[10] The application of marriage law equally to same-sex and opposite-sex couples has varied by jurisdiction, and has come about through legislative change to marriage law, court rulings based on constitutional guarantees of equality, recognition that marriage of same-sex couples is allowed by existing marriage law, and by direct popular vote, such as through referendums and initiatives.[11][12] The most prominent supporters of same-sex marriage are the world's major medical and scientific communities,[13][14][15] along with human rights and civil rights organizations,[16] while its most prominent opponents are religious fundamentalist groups.[17] Polls consistently show continually rising support for the recognition of same-sex marriage in all developed democracies and in many developing countries.

Scientific studies show that the financial, psychological, and physical well-being of gay people is enhanced by marriage, and that the children of same-sex parents benefit from being raised by married same-sex couples within a marital union that is recognized by law and supported by societal institutions. At the same time, no harm is done to the institution of marriage among heterosexuals.[18] Social science research indicates that the exclusion of same-sex couples from marriage stigmatizes and invites public discrimination against gay and lesbian people, with research repudiating the notion that either civilization or viable social orders depend upon restricting marriage to heterosexuals.[19][20][21] Same-sex marriage can provide those in committed same-sex relationships with relevant government services and make financial demands on them comparable to that required of those in opposite-sex marriages, and also gives them legal protections such as inheritance and hospital visitation rights.[22] Opposition is based on claims such as that homosexuality is unnatural and abnormal, that the recognition of same-sex unions will promote homosexuality in society, and that children are better off when raised by opposite-sex couples. These claims are refuted by scientific studies, which show that homosexuality is a natural and normal variation in human sexuality, that sexual orientation is not a choice, and that children of same-sex couples fare just as well as the children of opposite-sex couples.[13]

Terminology

Alternative terms

Some proponents of the legal recognition of same-sex marriage—such as Marriage Equality USA (founded in 1998), Freedom to Marry (founded in 2003), Canadians for Equal Marriage, and Marriage for All Japan - used the terms marriage equality and equal marriage to signal that their goal was for same-sex marriage to be recognized on equal ground with opposite-sex marriage.[23][24][25][26][27][28] The Associated Press recommends the use of same-sex marriage over gay marriage.[29] In deciding whether to use the term gay marriage, it may also be noted that not everyone in a same-sex marriage is gay – for example, some are bisexual – and therefore using the term gay marriage is sometimes considered erasure of such people.[30][31]

Use of the term marriage

Anthropologists have struggled to determine a definition of marriage that absorbs commonalities of the social construct across cultures around the world.[32][33] Many proposed definitions have been criticized for failing to recognize the existence of same-sex marriage in some cultures, including those of more than 30 African peoples, such as the Kikuyu and Nuer.[33][34][35]

With several countries revising their marriage laws to recognize same-sex couples in the 21st century, all major English dictionaries have revised their definition of the word marriage to either drop gender specifications or supplement them with secondary definitions to include gender-neutral language or explicit recognition of same-sex unions.[36][37] The Oxford English Dictionary has recognized same-sex marriage since 2000.[38]

Opponents of same-sex marriage who want marriage to be restricted to pairings of a man and a woman, such as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Catholic Church, and the Southern Baptist Convention, use the term traditional marriage to mean opposite-sex marriage.[17]

History

Ancient

A reference to marriage between same-sex couples appears in the Sifra, which was written in the 3rd century CE. The Book of Leviticus prohibited homosexual relations, and the Hebrews were warned not to "follow the acts of the land of Egypt or the acts of the land of Canaan" (Lev. 18:22, 20:13). The Sifra clarifies what these ambiguous "acts" were, and that they included marriage between same-sex couples: "A man would marry a man and a woman a woman, a man would marry a woman and her daughter, and a woman would be married to two men."[39]

A few scholars believe that in the early Roman Empire some male couples were celebrating traditional marriage rites in the presence of friends. Male–male weddings are reported by sources that mock them; the feelings of the participants are not recorded.[40] Various ancient sources state that the emperor Nero celebrated two public weddings with males, once taking the role of the bride (with a freedman Pythagoras), and once the groom (with Sporus); there may have been a third in which he was the bride.[41] In the early 3rd century AD, the emperor Elagabalus is reported to have been the bride in a wedding to his male partner. Other mature men at his court had husbands, or said they had husbands in imitation of the emperor.[42] Roman law did not recognize marriage between males, but one of the grounds for disapproval expressed in Juvenal's satire is that celebrating the rites would lead to expectations for such marriages to be registered officially.[43] As the empire was becoming Christianized in the 4th century, legal prohibitions against marriage between males began to appear.[43]

Contemporary

Michael McConnell and Jack Baker[3][4] are the first same sex couple in modern recorded history[5] known to obtain a marriage license,[6] have their marriage solemnized, which occurred on September 3, 1971, in Minnesota,[7] and have it legally recognized by any form of government.[8][9] Historians variously trace the beginning of the modern movement in support of same-sex marriage to anywhere from around the 1980s to the 1990s. During the 1980s in the United States, the AIDS epidemic led to increased attention on the legal aspects of same-sex relationships.[44] Andrew Sullivan made the first case for same sex marriage in a major American journal in 1989,[45] published in The New Republic.[46]

In 1989, Denmark became the first country to legally recognize a relationship for same-sex couples, establishing registered partnerships, which gave those in same-sex relationships "most rights of married heterosexuals, but not the right to adopt or obtain joint custody of a child".[47] In 2001, the continental Netherlands became the first country to broaden marriage laws to include same-sex couples.[10][48] Since then, same-sex marriage has been established by law in 34 other countries, including most of the Americas and Western Europe. Yet its spread has been uneven — South Africa is the only country in Africa to take the step; Taiwan and Thailand are the only ones in Asia.[49][50]

Timeline

The summary table below lists in chronological order the sovereign states (the United Nations member states and Taiwan) that have legalized same-sex marriage. As of 2025, 37 states have legalized in some capacity.[51]

Dates are when marriages between same-sex couples began to be officially certified, or when local laws were passed if marriages were already legal under higher authority.

Same-sex marriage around the world

Same-sex marriage is legally performed and recognized in 37 countries: Andorra, Argentina, Australia,[a] Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Denmark,[b] Ecuador,[c] Estonia, Finland, France,[d] Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico,[e] the Netherlands,[f] New Zealand,[g] Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, the United Kingdom,[h] the United States,[i] and Uruguay.[52] Same-sex marriage performed remotely or abroad is recognized with full marital rights by Israel.[53]

Same-sex marriage will begin to be performed by Thailand in January 2025, and is under consideration by the legislature or the courts in El Salvador,[54][55] Italy,[56][57] Japan,[58] Nepal,[j] and Venezuela.[62]

Civil unions are being considered in a number of countries, including Kosovo,[63] Peru,[64] and Poland.[65]

On 12 March 2015, the European Parliament passed a non-binding resolution encouraging EU institutions and member states to "[reflect] on the recognition of same-sex marriage or same-sex civil union as a political, social and human and civil rights issue".[66][67]

In response to the international spread of same-sex marriage, a number of countries have enacted preventative constitutional bans, with the most recent being Mali in 2023, and Gabon in 2024. In other countries, such restrictions and limitations are effected through legislation. Even before same-sex marriage was first legislated, some countries had constitutions that specified that marriage was between a man and a woman.

International court rulings

European Court of Human Rights

In 2010, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled in Schalk and Kopf v Austria, a case involving an Austrian same-sex couple who were denied the right to marry.[68] The court found, by a vote of 4 to 3, that their human rights had not been violated.[69] The court further stated that same-sex unions are not protected under art. 12 of ECHR ("Right to marry"), which exclusively protects the right to marry of opposite-sex couples (without regard if the sex of the partners is the result of birth or of sex change), but they are protected under art. 8 of ECHR ("Right to respect for private and family life") and art. 14 ("Prohibition of discrimination").[70]

Article 12 of the European Convention on Human Rights states that: "Men and women of marriageable age have the right to marry and to found a family, according to the national laws governing the exercise of this right",[71] not limiting marriage to those in a heterosexual relationship. However, the ECHR stated in Schalk and Kopf v Austria that this provision was intended to limit marriage to heterosexual relationships, as it used the term "men and women" instead of "everyone".[68] Nevertheless, the court accepted and is considering cases concerning same-sex marriage recognition, e.g. Andersen v Poland.[72] In 2021, the court ruled in Fedotova and Others v. Russia—followed by later judgements concerning other member states—that countries must provide some sort of legal recognition to same-sex couples, although not necessarily marriage.[73]

European Union

On 5 June 2018, the European Court of Justice ruled, in a case from Romania, that, under the specific conditions of the couple in question, married same-sex couples have the same residency rights as other married couples in an EU country, even if that country does not permit or recognize same-sex marriage.[74][75] However, the ruling was not implemented in Romania and on 14 September 2021 the European Parliament passed a resolution calling on the European Commission to ensure that the ruling is respected across the EU.[76][77]

Inter-American Court of Human Rights

On 8 January 2018, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) issued an advisory opinion that states party to the American Convention on Human Rights should grant same-sex couples accession to all existing domestic legal systems of family registration, including marriage, along with all rights that derive from marriage. The Court recommended that governments issue temporary decrees recognizing same-sex marriage until new legislation is brought in. They also said that it was inadmissible and discriminatory for a separate legal provision to be established (such as civil unions) instead of same-sex marriage.[78]

Other arrangements

Civil unions

Civil union, civil partnership, domestic partnership, registered partnership, unregistered partnership, and unregistered cohabitation statuses offer varying legal benefits of marriage. As of 12 January 2025, countries that have an alternative form of legal recognition other than marriage on a national level are: Bolivia, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Monaco, Montenegro and San Marino.[80][81] Same-sex marriage performed remotely or abroad is recognized with full marital rights by Israel. Poland offers more limited rights. Additionally, various cities and counties in Cambodia and Japan offer same-sex couples varying levels of benefits, which include hospital visitation rights and others.

Additionally, nineteen countries that have legally recognized same-sex marriage also have an alternative form of recognition for same-sex couples, usually available to heterosexual couples as well: Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, France, Greece, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, the United Kingdom and Uruguay.[82][83][84][85]

They are also available in parts of the United States (Arizona,[k] California, Colorado, Hawaii, Illinois, New Jersey, Nevada and Oregon) and Canada.[86][87]

Non-sexual same-sex marriage

Kenya

Female same-sex marriage is practiced among the Gikuyu, Nandi, Kamba, Kipsigis, and to a lesser extent neighboring peoples. About 5–10% of women are in such marriages. However, this is not seen as homosexual, but is instead a way for families without sons to keep their inheritance within the family.[88]

Nigeria

Among the Igbo people and probably other peoples in the south of the country, there are circumstances where a marriage between women is considered appropriate, such as when a woman has no child and her husband dies, and she takes a wife to perpetuate her inheritance and family lineage.[89]

Studies

The American Anthropological Association stated on 26 February 2004:

The results of more than a century of anthropological research on households, kinship relationships, and families, across cultures and through time, provide no support whatsoever for the view that either civilization or viable social orders depend upon marriage as an exclusively heterosexual institution. Rather, anthropological research supports the conclusion that a vast array of family types, including families built upon same-sex partnerships, can contribute to stable and humane societies.[21]

Research findings from 1998 to 2015 from the University of Virginia, Michigan State University, Florida State University, the University of Amsterdam, the New York State Psychiatric Institute, Stanford University, the University of California-San Francisco, the University of California-Los Angeles, Tufts University, Boston Medical Center, the Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, and independent researchers also support the findings of this study.[90][vague]

The overall socio-economic and health effects of legal access to same-sex marriage around the world have been summarized by Badgett and co-authors.[91] The review found that sexual minority individuals took-up legal marriage when it became available to them (but at lower rates than different-sex couples). There is instead no evidence that same-sex marriage legalization affected different-sex marriages. On the health side, same-sex marriage legalization increased health insurance coverage for individuals in same-sex couples (in the US), and it led to improvements in sexual health among men who have sex with men, while there is mixed evidence on mental health effects among sexual minorities. In addition, the study found mixed evidence on a range of downstream social outcomes such as attitudes toward LGBTQ+ people and employment choices of sexual minorities.

Health

As of 2006[update], the data of current psychological and other social science studies on same-sex marriage in comparison to mixed-sex marriage indicate that same-sex and mixed-sex relationships do not differ in their essential psychosocial dimensions; that a parent's sexual orientation is unrelated to their ability to provide a healthy and nurturing family environment; and that marriage bestows substantial psychological, social, and health benefits. Same-sex parents and carers and their children are likely to benefit in numerous ways from legal recognition of their families, and providing such recognition through marriage will bestow greater benefit than civil unions or domestic partnerships.[92][93][needs update] Studies in the United States have correlated legalization of same-sex marriage to lower rates of HIV infection,[94][95] psychiatric disorders,[96][97] and suicide rate in the LGBT population.[98][99]

Issues

While few societies have recognized same-sex unions as marriages,[needs update] the historical and anthropological record reveals a large range of attitudes towards same-sex unions ranging from praise, through full acceptance and integration, sympathetic toleration, indifference, prohibition and discrimination, to persecution and physical annihilation.[citation needed] Opponents of same-sex marriages have argued that same-sex marriage, while doing good for the couples that participate in them and the children they are raising,[100] undermines a right of children to be raised by their biological mother and father.[101] Some supporters of same-sex marriages take the view that the government should have no role in regulating personal relationships,[102] while others argue that same-sex marriages would provide social benefits to same-sex couples.[l] The debate regarding same-sex marriages includes debate based upon social viewpoints as well as debate based on majority rules, religious convictions, economic arguments, health-related concerns, and a variety of other issues.[citation needed]

Parenting

Scientific literature indicates that parents' financial, psychological and physical well-being is enhanced by marriage and that children benefit from being raised by two parents within a legally recognized union (either a mixed-sex or same-sex union). As a result, professional scientific associations have argued for same-sex marriage to be legally recognized as it will be beneficial to the children of same-sex parents or carers.[14][15][103][104][105]

Scientific research has been generally consistent in showing that lesbian and gay parents are as fit and capable as heterosexual parents, and their children are as psychologically healthy and well-adjusted as children reared by heterosexual parents.[15][105][106][107] According to scientific literature reviews, there is no evidence to the contrary.[92][108][109][110][needs update]

Compared to heterosexual couples, same-sex couples have a greater need for adoption or assisted reproductive technology to become parents. Lesbian couples often use artificial insemination to achieve pregnancy, and reciprocal in vitro fertilization (where one woman provides the egg and the other gestates the child) is becoming more popular in the 2020s, although many couples cannot afford it. Surrogacy is an option for wealthier gay male couples, but the cost is prohibitive. Other same-sex couples adopt children or raise the children from earlier opposite-sex relationships.[111][112]

Adoption

All states that allow same-sex marriage also allow the joint adoption of children by those couples with the exception of Ecuador and a third of states in Mexico, though such restrictions have been ruled unconstitutional in Mexico. In addition, Bolivia, Croatia, Israel and Liechtenstein, which do not recognize same-sex marriage, nonetheless permit joint adoption by same-sex couples. Some additional states do not recognize same-sex marriage but allow stepchild adoption by couples in civil unions, namely the Czech Republic and San Marino.[citation needed]

Transgender and intersex people

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material that does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (May 2017) |

The legal status of same-sex marriage may have implications for the marriages of couples in which one or both parties are transgender, depending on how sex is defined within a jurisdiction. Transgender and intersex individuals may be prohibited from marrying partners of the "opposite" sex or permitted to marry partners of the "same" sex due to legal distinctions.[citation needed] In any legal jurisdiction where marriages are defined without distinction of a requirement of a male and female, these complications do not occur. In addition, some legal jurisdictions recognize a legal and official change of gender, which would allow a transgender male or female to be legally married in accordance with an adopted gender identity.[113]

In the United Kingdom, the Gender Recognition Act 2004 allows a person who has lived in their chosen gender for at least two years to receive a gender recognition certificate officially recognizing their new gender. Because in the United Kingdom marriages were until recently only for mixed-sex couples and civil partnerships are only for same-sex couples, a person had to dissolve their civil partnership before obtaining a gender recognition certificate[citation needed], and the same was formerly true for marriages in England and Wales, and still is in other territories. Such people are then free to enter or re-enter civil partnerships or marriages in accordance with their newly recognized gender identity. In Austria, a similar provision requiring transsexual people to divorce before having their legal sex marker corrected was found to be unconstitutional in 2006.[114] In Quebec, prior to the legalization of same-sex marriage, only unmarried people could apply for legal change of gender. With the advent of same-sex marriage, this restriction was dropped. A similar provision including sterilization also existed in Sweden, but was phased out in 2013.[115] In the United States, transgender and intersex marriages was subject to legal complications.[116] As definitions and enforcement of marriage are defined by the states, these complications vary from state to state,[117] as some of them prohibit legal changes of gender.[118]

Divorce

In the United States before the case of Obergefell v. Hodges, couples in same-sex marriages could only obtain a divorce in jurisdictions that recognized same-sex marriages, with some exceptions.[119]

Judicial and legislative

There are differing positions regarding the manner in which same-sex marriage has been introduced into democratic jurisdictions. A "majority rules" position holds that same-sex marriage is valid, or void and illegal, based upon whether it has been accepted by a simple majority of voters or of their elected representatives.[120]

In contrast, a civil rights view holds that the institution can be validly created through the ruling of an impartial judiciary carefully examining the questioning and finding that the right to marry regardless of the gender of the participants is guaranteed under the civil rights laws of the jurisdiction.[16]

Public opinion

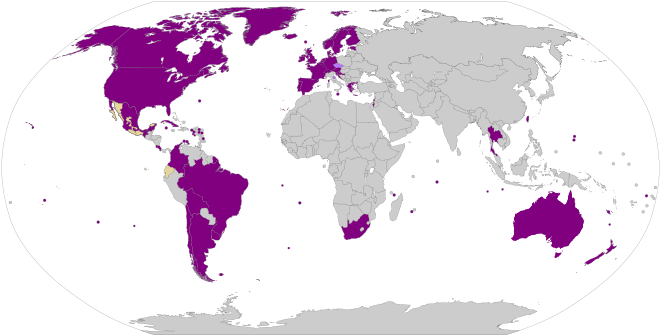

| 5⁄6+ 2⁄3+ | 1⁄2+ 1⁄3+ | 1⁄6+ <1⁄6 | no polls |

Numerous polls and studies on the issue have been conducted. A trend of increasing support for same-sex marriage has been revealed across many countries of the world, often driven in large part by a generational difference in support. Polling that was conducted in developed democracies in this century shows a majority of people in support of same-sex marriage. Support for same-sex marriage has increased across every age group, political ideology, religion, gender, race and region of various developed countries in the world.[122][123][124][125][126][needs update]

Various detailed polls and studies on same-sex marriage that were conducted in several countries show that support for same-sex marriage significantly increases with higher levels of education and is also significantly stronger among younger generations, with a clear trend of continually increasing support.[127]

- Greater support with youth

Pew Research polling results from 32 countries found 21 with statistically higher support for same-sex marriage among those under 35 than among those over 35 in 2022–2023. Countries with the greatest absolute difference are placed to the left in the following chart. Countries without a significant generational difference are placed to the right.[127]

- over 35

- additional support from those under 35

A 2016 survey by the Varkey Foundation found similarly high support of same-sex marriage (63%) among 18–21-year-olds in an online survey of 18 countries around the world.[128][129][130]

(The sampling error is approx. 4% for Nigeria and 3% for the other countries. Because of legal constraints, the question on same-sex marriage was not asked in the survey countries of Russia and Indonesia.)

- Opinion polls for same-sex marriage by country

| Country | Pollster | Year | For[m] | Against[m] | Neither[n] | Margin of error |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPSOS | 2023 | 26% |

73% (74%) |

1% | [131] | ||

| Institut d'Estudis Andorrans | 2013 | 70% (79%) |

19% (21%) |

11% | [132] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 12% | – | – | [133] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 69% (81%) |

16% [9% support some rights] (19%) |

15% not sure | ±5% | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 67% (72%) |

26% (28%) |

7% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2015 | 3% (3%) |

96% (97%) |

1% | ±3% | [136] [137] | |

| 2021 | 46% |

[138] | |||||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 64% (73%) |

25% [13% support some rights] (28%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 75% (77%) |

23% | 2% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 65% (68%) |

30% (32%) |

5% | [139] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2015 | 11% | – | – | [140] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2015 | 16% (16%) |

81% (84%) |

3% | ±4% | [136] [137] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 69% (78%) |

19% [9% support some rights] (22%) |

12% not sure | ±5% | [134] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 79% | 19% | 2% not sure | [139] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 8% | – | – | [140] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 35% | 65% | – | ±1.0% | [133] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 26% (27%) |

71% (73%) |

3% | [131] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 51% (62%) |

31% [17% support some rights] (38%) |

18% not sure | ±3.5% [o] | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 52% (57%) |

40% (43%) |

8% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 17% (18%) |

75% (82%) |

8% | [139] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 57% (58%) |

42% | 1% | [135] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 65% (75%) |

22% [10% support some rights] (25%) |

13% not sure | ±3.5% | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 79% (84%) |

15% (16%) |

6% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Cadem | 2024 | 77% (82%) |

22% (18%) |

2% | ±3.6% | [141] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2021 | 43% (52%) |

39% [20% support some rights] (48%) |

18% not sure | ±3.5% [o] | [142] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 46% (58%) |

33% [19% support some rights] (42%) |

21% | ±5% [o] | [134] | |

| CIEP | 2018 | 35% | 64% | 1% | [143] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 42% (45%) |

51% (55%) |

7% | [139] | ||

| Apretaste | 2019 | 63% | 37% | – | [144] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 50% (53%) |

44% (47%) |

6% | [139] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 60% | 34% | 6% | [139] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 93% | 5% | 2% | [139] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 10% | 90% | – | ±1.1% | [133] | |

| CDN 37 | 2018 | 45% | 55% | - | [145] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2019 | 23% (31%) |

51% (69%) |

26% | [146] | ||

| Universidad Francisco Gavidia | 2021 | 82.5% | – | [147] | |||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 41% (45%) |

51% (55%) |

8% | [139] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 76% (81%) |

18% (19%) |

6% | [139] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 62% (70%) |

26% [16% support some rights] (30%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 82% (85%) |

14% (15%) |

4% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 79% (85%) |

14 (%) (15%) |

7% | [139] | ||

| Women's Initiatives Supporting Group | 2021 | 10% (12%) |

75% (88%) |

15% | [148] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 73% (83%) |

18% [10% support some rights] (20%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 80% (82%) |

18% | 2% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 84% (87%) |

13%< | 3% | [139] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 48% (49%) |

49% (51%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 57% (59%) |

40% (41%) |

3% | [139] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 12% | 88% | – | ±1.4%c | [133] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 23% | 77% | – | ±1.1% | [133] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 21% | 79% | – | ±1.3% | [140] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 5% | 95% | – | ±0.3% | [133] | |

| CID Gallup | 2018 | 17% (18%) |

75% (82%) |

8% | [149] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 58% (59%) |

40% (41%) |

2% | [135] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 44% (56%) |

35% [18% support some rights] (44%) |

21% not sure | ±5% | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 31% (33%) |

64% (67%) |

5% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 42% (45%) |

52% (55%) |

6% | [139] | ||

| Gallup | 2006 | 89% | 11% | – | [150] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 53% (55%) |

43% (45%) |

4% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 5% | 92% (95%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 68% (76%) |

21% [8% support some rights] (23%) |

10% | ±5%[o] | [134] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 86% (91%) |

9% | 5% | [139] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 36% (39%) |

56% (61%) |

8% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 58% (66%) |

29% [19% support some rights] (33%) |

12% not sure | ±3.5% | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 73% (75%) |

25% | 2% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 69% (72%) |

27% (28%) |

4% | [139] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 16% | 84% | – | ±1.0% | [133] | |

| Kyodo News | 2023 | 64% (72%) |

25% (28%) |

11% | [151] | ||

| Asahi Shimbun | 2023 | 72% (80%) |

18% (20%) |

10% | [152] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 42% (54%) |

31% [25% support some rights] (40%) |

22% not sure | ±3.5% | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 68% (72%) |

26% (28%) |

6% | ±2.75% | [135] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2016 | 7% (7%) |

89% (93%) |

4% | [136] [137] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 9% | 90% (91%) |

1% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 20% (21%) |

77% (79%) |

3% | [131] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 36% | 59% | 5% | [139] | ||

| Liechtenstein Institut | 2021 | 72% | 28% | 0% | [153] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 39% | 55% | 6% | [139] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 84% | 13% | 3% | [139] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 17% | 82% (83%) |

1% | [135] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 74% | 24% | 2% | [139] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 55% | 29% [16% support some rights] | 17% not sure | ±3.5%[o] | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 63% (66%) |

32% (34%) |

5% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Europa Libera Moldova | 2022 | 14% | 86% | [154] | |||

| IPSOS | 2023 | 36% (37%) |

61% (63%) |

3% | [131] | ||

| Lambda | 2017 | 28% (32%) |

60% (68%) |

12% | [155] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 77% | 15% [8% support some rights] | 8% not sure | ±5% | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 89% (90%) |

10% | 1% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 94% | 5% | 2% | [139] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 70% (78%) |

20% [11% support some rights] (22%) |

9% | ±3.5% | [156] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 25% | 75% | – | ±1.0% | [133] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 2% | 97% (98%) |

1% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 20% (21%) |

78% (80%) |

2% | [131] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2017 | 72% (79%) |

19% (21%) |

9% | [136] [137] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 22% | 78% | – | ±1.1% | [133] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 26% | 74% | – | ±0.9% | [133] | |

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 36% |

44% [30% support some rights] | 20% | ±5% [o] | [134] | |

| SWS | 2018 | 22% (26%) |

61% (73%) |

16% | [157] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 51% (54%) |

43% (46%) |

6% | [158] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 41% (43%) |

54% (57%) |

5% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| United Surveys by IBRiS | 2024 | 50% (55%) |

41% (45%) |

9% | [159] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 50% | 45% | 5% | [139] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 80% (84%) |

15% [11% support some rights] (16%) |

5% | [156] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 81% | 14% | 5% | [139] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 25% (30%) |

59% [26% support some rights] (70%) |

17% | ±3.5% | [156] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 25% | 69% | 6% | [139] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2021 | 17% (21%) |

64% [12% support some rights] (79%) |

20% not sure | ±4.8% [o] | [142] | |

| FOM | 2019 | 7% (8%) |

85% (92%) |

8% | ±3.6% | [160] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 9% | 91% | – | ±1.0% | [133] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 11% | 89% | – | ±0.9% | [133] | |

| AmericasBarometer | 2017 | 4% | 96% | – | ±0.6% | [133] | |

| IPSOS | 2023 | 24% (25%) |

73% (75%) |

3% | [131] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 33% | 46% [21% support some rights] | 21% | ±5% [o] | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 45% (47%) |

51% (53%) |

4% | [135] | ||

| Focus | 2024 | 36% (38%) |

60% (62%) |

4% | [161] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 37% | 56% | 7% | [139] | ||

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 62% (64%) |

37% (36%) |

2% | [139] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 53% | 32% [14% support some rights] | 13% | ±5% [o] | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 38% (39%) |

59% (61%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 36% | 37% [16% support some rights] | 27% not sure | ±5% | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 41% (42%) |

56% (58%) |

3% | [135] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 73% (80%) |

19% [13% support some rights] (21%) |

9% not sure | ±3.5% | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 87% (90%) |

10% | 3% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 88% (91%) |

9% (10%) |

3% | [139] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 23% (25%) |

69% (75%) |

8% | [135] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 18% | – | – | [140] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 78% (84%) |

15% [8% support some rights] (16%) |

7% not sure | ±5% | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 92% (94%) |

6% | 2% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Eurobarometer | 2023 | 94% | 5% | 1% | [139] | ||

| Ipsos | 2023 | 54% (61%) |

34% [16% support some rights] (39%) |

13% not sure | ±3.5% | [156] | |

| CNA | 2023 | 63% | 37% | [162] | |||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 45% (51%) |

43% (49%) |

12% | [135] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 58% | 29% [20% support some rights] | 12% not sure | ±5%[o] | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 60% (65%) |

32% (35%) |

8% | [135] | ||

| AmericasBarometer | 2014 | 16% | – | – | [140] | ||

| Ipsos (more urban/educated than representative) | 2024 | 18% (26%) |

52% [19% support some rights] (74%) |

30% not sure | ±5% [o] | [134] | |

| Rating | 2023 | 37% (47%) |

42% (53%) |

22% | ±1.5% | [163] | |

| YouGov | 2023 | 77% (84%) |

15% (16%) |

8% | [164] | ||

| Ipsos | 2024 | 66% (73%) |

24% [11% support some rights] (27%) |

10% not sure | ±3.5% | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 74% (77%) |

22% (23%) |

4% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| Ipsos | 2024 | 51% (62%) |

32% [14% support some rights] (39%) |

18% not sure | ±3.5% | [134] | |

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 63% (65%) |

34% (35%) |

3% | ±3.6% | [135] | |

| LatinoBarómetro | 2023 | 78% (80%) |

20% | 2% | [165] | ||

| Equilibrium Cende | 2023 | 55% (63%) |

32% (37%) |

13% | [166] | ||

| Pew Research Center | 2023 | 65% (68%) |

30% (32%) |

5% | [156] |

See also

- LGBT rights by country or territory

- List of same-sex married couples

- Religion and sexuality

- Legal status of same-sex marriage

- Societal attitudes toward homosexuality

Notes

- ^ Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized by law in continental Australia and in the non-self-governing possessions of Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and the Cocos Islands, which follow Australian law.

- ^ Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized by law in continental Denmark, the Faroe Islands and Greenland, which together make up the Realm of Denmark.

- ^ Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized throughout Ecuador, but such couples are not considered married for purposes of adoption and may not adopt children.

- ^ Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized by law in metropolitan France and in all French overseas regions and possessions, which follow a single legal code.

- ^ Same-sex marriage is available in all jurisdictions, though the process is not everywhere as straightforward as it is for opposite-sex marriage and does not always include adoption rights.

- ^ Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized by law in the continental Netherlands, the Caribbean municipalities of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba, and the constituent countries of Aruba and Curaçao, but not yet in Sint Maarten.

- ^ Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized by law in New Zealand proper, but not in its possession of Tokelau, nor in the Cook Islands and Niue, which make up the Realm of New Zealand.

- ^ Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized by law in all parts of the United Kingdom and in its non-Caribbean possessions, but not in its Caribbean possessions, namely Anguilla, Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, Montserrat and the Turks and Caicos Islands.

- ^ Same-sex marriage is performed and recognized by law in all fifty states of the US and in the District of Columbia, in all overseas territories except American Samoa (recognition only), and in all tribal nations that do not have their own marriage laws, as well as in most nations that do. The largest of the dozen or so known exceptions among the federal reservations are Navajo and Gila River, and the largest among the shared-sovereignty Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Areas are the Creek and Citizen Potawatomi. These polities ban same-sex marriage and do not recognize marriages from other jurisdictions, though members may still marry under state law and be accorded all the rights of marriage under state and federal law.

- ^ Nepal is waiting for a final decision by its supreme court, but meanwhile all local governments are ordered to temporarily register same-sex marriages in a separate record. In April 2024 the National ID and Civil Registration Department issued a circular to all local governments that they register such marriages. However, simply being registered does not grant same-sex couples the legal rights of marriage, and registered same-sex couples cannot inherit property, get tax subsidies, make spousal medical decisions, adopt children etc.[59][60][61]

- ^ Legally available in the Arizona municipalities of Bisbee, Clarkdale, Cottonwood, Jerome, Sedona and Tucson.

- ^ Dale Carpenter is a prominent spokesman for this view. For a better understanding of this view, see Carpenter's writings at "Dale Carpenter". Independent Gay Forum. Archived from the original on 17 November 2006. Retrieved 31 October 2006.

- ^ a b Because some polls do not report 'neither', those that do are listed with simple yes/no percentages in parentheses, so their figures can be compared.

- ^ Comprises: Neutral; Don't know; No answer; Other; Refused.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k [+ more urban/educated than representative]

References

- ^ VERPOEST, LIEN (2017). "The End of Rhetorics: LGBT policies in Russia and the European Union". Studia Diplomatica. 68 (4): 3–20. ISSN 0770-2965. JSTOR 26531664.

- ^ Williams, CA., Roman Homosexuality: Second Edition, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 280, p. 284.

- ^ a b Padnani, Amisha; Fang, Celina (26 June 2015). "Same-Sex Marriage: Landmark Decisions and Precedents". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Baume, Matt (1 March 2019). "Meet the Gay Men Whose 1971 Marriage Was Finally Recognized". The Advocate.

- ^ a b StoryCorps Archive (September 12, 2017). "Michael McConnell, Jack Baker, and Lisa Vecoli".

- Michael McConnell (75) and husband Jack Baker (75) talk with friend Lisa Vecoli (55) about having the first same-sex marriage legally recognized by a U.S. civil government in 1971, why they chose to get married, and what the response to their marriage was like.

- JB describes the decades-long (46-year) process from the denial of their marriage license in 1971 until a second request that same year in Blue Earth County, Minnesota, was "declared to be in all respects valid" by Order of Gregory J. Anderson, Judge of District Court.

- ^ a b Newsletter, "Hidden Treasures from the Stacks", The National Archives at Kansas City, p. 6 (September 2013).

- ^ a b Source: Blue Earth County

- Certificate 434960: Minnesota Official Marriage System

- Applicants: James Michael McConnell and Pat Lyn McConnell

- Date of Marriage: September 3, 1971

- Certified Copy: Marriage Certificate

- ^ a b "The September 3, 1971 marriage of James Michael McConnell and Pat Lyn McConnell, a/k/a Richard John Baker, has never been dissolved or annulled by judicial decree and no grounds currently exist on which to invalidate the marriage."

- Sources: CONCLUSIONS OF LAW by Assistant Chief Judge Gregory Anderson, Fifth Judicial District, (page 4);

- Copy: Minnesota Judicial Branch, File Number 07-CV-16-4559, "Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Order for Partial Summary Judgment" from Blue Earth County District Court in re James Michael McConnell et al. v. Blue Earth County et al. (September 18, 2018);

- Available online from U of M Libraries;

- McConnell Files, "America’s First Gay Marriage" (binder #4), Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries.

- ^ a b Michael McConnell, with Jack Baker, as told to Gail Langer Karwoski, "The Wedding Heard Heard 'Round the World: America's First Gay Marriage Archived August 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine". University of Minnesota Press (2016). Reprint, "With A New Epilogue" (2020).

- ^ a b Winter, Caroline (4 December 2014). "In 14 years, same-sex marriage has spread round the world". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "Same-sex Oklahoma couple marries legally under tribal law". KOCO. 26 September 2013. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ "Clela Rorex, former Boulder County Clerk who issued first same-sex marriage license in 1975 dies at 78". 19 June 2022.

- ^ a b Multiple sources:

- Coghlan, Andy (16 June 2008). "Gay brains structured like those of the opposite sex". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Lamanna, Mary Ann; Riedmann, Agnes; Stewart, Susan D. (2014). Marriages, Families, and Relationships: Making Choices in a Diverse Society. Cengage Learning. p. 82. ISBN 978-1305176898. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

[T]he APA says that sexual orientation is not a choice [...]. (American Psychological Association, 2010).

- Pawelski, J. G.; Perrin, E. C.; Foy, J. M.; Allen, C. E.; Crawford, J. E.; Del Monte, M.; Kaufman, M.; Klein, J. D.; Smith, K.; Springer, S.; Tanner, J. L.; Vickers, D. L. (2006). "The Effects of Marriage, Civil Union, and Domestic Partnership Laws on the Health and Well-being of Children". Pediatrics. 118 (1): 349–364. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1279. PMID 16818585. S2CID 219194821. Archived from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- American Medical Association; American Academy of Pediatrics; American Psychological Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy; National Association of Social Workers; American Psychoanalytic Association; American Academy of Family Physicians; et al. "Brief of [medical organizations] as Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners" (PDF). supremecourt.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Bever, Lindsey (7 July 2014). "Children of same-sex couples are happier and healthier than peers, research shows". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- Pawelski, James G.; Perrin, Ellen C.; Foy, Jane M.; Allen, Carole E.; Crawford, James E.; Del Monte, Mark; Kaufman, Miriam; Klein, Jonathan D.; Smith, Karen; Springer, Sarah; Tanner, J. Lane; Vickers, Dennis L. (July 2006). "The Effects of Marriage, Civil Union, and Domestic Partnership Laws on the Health and Well-being of Children". Pediatrics. 118 (1). American Academy of Pediatrics: 349–64. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1279. PMID 16818585. S2CID 219194821. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

In fact, growing up with parents who are lesbian or gay may confer some advantages to children.

- ^ a b "Brief of the American Psychological Association, The California Psychological Association, the American Psychiatric Association, and the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy as amici curiae in support of plaintiff-appellees – Appeal from United States District Court for the Northern District of California Civil Case No. 09-CV-2292 VRW (Honorable Vaughn R. Walker)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ a b c "Marriage of Same-Sex Couples – 2006 Position Statement Canadian Psychological Association" (PDF). 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2009.

- ^ a b Mirchandani, Rajesh (12 November 2008). "Divisions persist over gay marriage ban". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ a b "The Divine Institution of Marriage". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 13 August 2008. Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ Molly Ball, 2024 May 13, Wall Street Journal, How 20 Years of Same-Sex Marriage Changed America

- ^ Multiple sources:

- "Resolution on Sexual Orientation and Marriage" (PDF). American Psychological Association. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- "Brief of the American Psychological Association, The California Psychological Association, the American Psychiatric Association, and the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy as amici curiae in support of plaintiff-appellees – Appeal from United States District Court for the Northern District of California Civil Case No. 09-CV-2292 VRW (Honorable Vaughn R. Walker)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- "Marriage of Same-Sex Couples – 2006 Position Statement" (PDF). Canadian Psychological Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- Pawelski JG, Perrin EC, Foy JM, et al. (July 2006). "The effects of marriage, civil union, and domestic partnership laws on the health and well-being of children". Pediatrics. 118 (1): 349–64. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1279. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 16818585. S2CID 219194821.

- Pawelski, J. G.; Perrin, E. C.; Foy, J. M.; Allen, C. E.; Crawford, J. E.; Del Monte, M.; Kaufman, M.; Klein, J. D.; Smith, K.; Springer, S.; Tanner, J. L.; Vickers, D. L. (2006). "The Effects of Marriage, Civil Union, and Domestic Partnership Laws on the Health and Well-being of Children". Pediatrics. 118 (1): 349–364. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1279. PMID 16818585. S2CID 219194821. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ "Brief of Amici Curiae American Anthropological Association et al., supporting plaintiffs-appellees and urging affirmance – Appeal from United States District Court for the Northern District of California Civil Case No. 09-CV-2292 VRW (Honorable Vaughn R. Walker)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ a b American Anthropological Association (2004). "Statement on Marriage and the Family". Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ Handbook of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Administration and Policy — Page 13, Wallace Swan – 2004

- ^ "Marriage Equality". Garden State Equality. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ "Marriage 101". Freedom to Marry. Archived from the original on 16 February 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ Pratt, Patricia (29 May 2012). "Albany area real estate and the Marriage Equality Act". Albany Examiner. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

On July 24, 2011 the Marriage Equality Act became a law in New York State forever changing the state's legal view of what a married couple is.

- ^ "Vote on Illinois marriage equality bill coming in January: sponsors". Chicago Phoenix. 13 December 2012. Archived from the original on 26 December 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ Mulholland, Helene (27 September 2012). "Ed Miliband calls for gay marriage equality". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ Ring, Trudy (20 December 2012). "Newt Gingrich: Marriage Equality Inevitable, OK". The Advocate. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

He [Newt Gingrich] noted to HuffPo that he not only has a lesbian half-sister, LGBT rights activist Candace Gingrich, but has gay friends who've gotten married in Iowa, where their unions are legal. Public opinion has shifted in favor of marriage equality, he said, and the Republican Party could end up on the wrong side of history if it continues to go against the tide.

- ^ APStylebook [@APStylebook] (12 February 2019). "The term same-sex marriage is preferred over gay marriage. In places where it's legal, same-sex marriage is no different from other marriages, so the term should be used only when germane and needed to distinguish from marriages between heterosexual couples. #APStyleChat" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 19 October 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ "One in 10 LGBT Americans Married to Same-Sex Spouse". Gallup. 24 February 2021.

- ^ Yin, Karen (8 March 2016). "When Bisexual People Marry". Conscious Style Guide.

- ^ Fedorak, Shirley A. (2008). Anthropology matters!. [Toronto], Ont.: University of Toronto Press. pp. Ch. 11, p. 174. ISBN 978-1442601086.

- ^ a b Gough, Kathleen E. (January–June 1959). "The Nayars and the Definition of Marriage". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 89 (1): 23–34. doi:10.2307/2844434. JSTOR 2844434.

- ^ Murray, Stephen O.; Roscoe, Will (2001). Boy-wives and female husbands : studies of African homosexualities (1st pbk. ed.). New York: St. Martin's. ISBN 978-0312238292. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Njambi, Wairimu; O'Brien, William (Spring 2001). "Revisiting "Woman-Woman Marriage": Notes on Gikuyu Women". NWSA Journal. 12 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1353/nwsa.2000.0015. S2CID 144520611. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ "Dictionaries take lead in redefining modern marriage". The Washington Times. 24 May 2004. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ "Webster Makes It Official: Definition of Marriage Has Changed". American Bar Association. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ Redman, Daniel (7 April 2009). "Noah Webster Gives His Blessing: Dictionaries recognize same-sex marriage—who knew?". Slate. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ Rabbi Joel Roth. Homosexuality Archived 24 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine rabbinicalassembly.org 1992.

- ^ Martial 1.24 and 12.42; Juvenal 2.117–42. Williams, Roman Homosexuality, pp. 28, 280; Karen K. Hersh, The Roman Wedding: Ritual and Meaning in Antiquity (Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 36; Caroline Vout, Power and Eroticism in Imperial Rome (Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 151ff.

- ^ Suetonius, Tacitus, Dio Cassius, and Aurelius Victor are the sources cited by Williams, Roman Homosexuality, p. 279.

- ^ Williams, Roman Homosexuality, pp. 278–279, citing Dio Cassius and Aelius Lampridius.

- ^ a b Williams, Roman Homosexuality, p. 280.

- ^ "How Same-Sex Marriage Came to Be". Harvard Magazine. March–April 2013. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ Hari, Johann (Spring 2009). "Andrew Sullivan: Thinking. Out. Loud". Intelligent Life. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (9 November 2012). "Here Comes the Groom". Slate. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^ Rule, Sheila (2 October 1989). "Rights for Gay Couples in Denmark". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ "Same-sex marriage around the world". CBC News. Toronto. 26 May 2009. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ "The Dutch went first in 2001; who has same-sex marriage now?". Associated Press. 28 April 2021. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ Sangwongwanich, Pathom (18 June 2024). "Thai Same-Sex Marriage Bill Clears Final Hurdle With Senate Nod". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ Theil, Michele (16 February 2024). "This map shows you where same-sex marriage is legal around the world – and there's a long way to go". PinkNews. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "Marriage Equality Around the World". Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ "Information for couples marrying outside the Rabbinate" (PDF). Rackman Center. 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "Sala de lo Constitucional resolvería demanda sobre matrimonio igualitario en los primeros tres messes de 2020". elsalvador.com (in Spanish). 6 January 2020.

- ^ "Bukele busca que se apruebe el aborto terapéutico y la unión homosexual". El Observador (in Spanish). 18 August 2021.

- ^ "Diritti: matrimonio "egualitario". Opinioni a confronto: Scalfarotto vs Bonaldi vs Centinaio". 9 March 2023. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "Da Zaia a Centinaio: la Lega ora cambia sui diritti lgbt (e c'entra "l'effetto Francesca")". 10 March 2023. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "Japan opposition party submits bill for same-sex marriage". Kyodo News. 6 March 2023. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ Raut, Swechhya (10 July 2024). "Nepal: Same-sex couples face hurdles on road to recognition". DW.

- ^ Ghimire, Binod (3 December 2023). "How court laid the ground for same-sex marriage in Nepal". The Kathmandu Post.

- ^ Dhakal, Manisha. "The Long Road to Lasting Marriage Equality in Nepal". APCOM.

- ^ "Diputada plantea iniciativa para el matrimonio civil igualitario en la Asamblea Nacional". El Acarigueño (in Spanish). 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Alice; Alipour, Nick (26 April 2024). "Kosovo promises to introduce same-sex unions in May". www.euractiv.com.

- ^ "Presentan proyecto de ley sobre el matrimonio igualitario entre personas del mismo sexo". El Comercio. elcomercio.pe. 23 October 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Duffy, Nick (13 March 2015). "UKIP and Tories abstain on EU motion to recognise same-sex marriage". PinkNews. Archived from the original on 9 August 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ "Texts adopted – Thursday, 12 March 2015 – Annual report on human rights and democracy in the world 2013 and the EU policy on the matter". European Parliament. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ a b "HUDOC – European Court of Human Rights". Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ Buyse, Antoine (24 June 2010). "Strasbourg court rules that states are not obliged to allow gay marriage". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ Avram, Marieta (2016). Drept civil Familia [Civil law Family] (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Hamangiu. ISBN 978-606-27-0609-8.

- ^ "European Convention on Human Rights" (PDF). ECHR.coe.int. European Court of Human Rights. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ "HUDOC - European Court of Human Rights". ECHR. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ Palazzo, Nausica (April 2023). "Fedotova and Others v. Russia : Dawn of a new era for European LGBTQ families?". Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law. 30 (2): 216–228. doi:10.1177/1023263X231195455. S2CID 261655476.

- ^ "EU court backs residency rights for gay couple in Romania". Associated Press. 5 June 2018. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "Same-sex spouses have EU residence rights, top court rules – BBC". BBC News. 5 June 2018. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "Texts adopted – LGBTIQ rights in the EU – Tuesday, 14 September 2021". European Parliament. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ "MEPs condemn failure to respect rights of same-sex partners in EU". The Guardian. 14 September 2021. Archived from the original on 14 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ "Major Advance for Marriage Equality and Gender Identity Rights in Latin America". San Francisco Bay Times. Sfbaytimes.com. 25 January 2018. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Towle, Andy (13 November 2008). "NYC Protest and Civil Rights March Opposing Proposition 8". Towleroad. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ Pearson, Mary. "Where is Gay Marriage Legal?". christiangays.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ Williams, Steve. "Which Countries Have Legalized Gay Marriage?". Care2.com (news.bbc.co.uk as source). Archived from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Loi du 9 juillet 2004 relative aux effets légaux de certains partenariats. – Legilux". Eli.legilux.public.lu. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ "Loi n° 99-944 du 15 novembre 1999 relative au pacte civil de solidarité". Legifrance.gouv.fr (in French). 12 March 2007. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ "WETTEN, DECRETEN, ORDONNANTIES EN VERORDENINGEN LOIS, DECRETS, ORDONNANCES ET REGLEMENTS" (PDF). Ejustice.jkust.fgov.be. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ "Civil Partnership Act 2004". Legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ "Same-Sex Marriage, Civil Unions and Domestic Partnerships". National Conference of State Legislatures. Archived from the original on 10 June 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ Ramstack, Tom (11 January 2010). "Congress Considers Outcome of D.C. Gay Marriage Legislation". AHN. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010.

- ^ Gender and Language in Sub-Saharan Africa, 2013:35

- ^ Igwe, Leo (19 June 2009). "Tradition of same gender marriage in Igboland". Nigerian Tribune. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010.

- ^ "Same-sex marriage and children's well-being: Research roundup". Journalist's Resource. 26 June 2015. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ Badgett, M.V. Lee; Carpenter, Christopher S.; Lee, Maxine J.; Sansone, Dario (2024). "A review of the effects of legal access to same-sex marriage". Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. doi:10.1002/pam.22587. hdl:10871/135707.

- ^ a b Pawelski, J.G.; Perrin, E.C.; Foy, J.M.; Allen, C.E.; Crawford, J.E.; Del Monte, M.; Kaufman, M.; Klein, J.D.; Smith, K.; Springer, S.; Tanner, J.L.; Vickers, D.L. (2006). "The Effects of Marriage, Civil Union, and Domestic Partnership Laws on the Health and Well-being of Children". Pediatrics. 118 (1): 349–64. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1279. PMID 16818585. S2CID 219194821.

- ^ Herek, Gregory M. "Legal recognition of same-sex relationships in the United States: A social science perspective." American Psychologist, Vol 61(6), September 2006, pp. 607–21.

- ^ Elaine Justice. "Study Links Gay Marriage Bans to Rise in HIV infections". Emory University. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Peng, Handie. "The Effect of Same-Sex Marriage Laws on Public Health and Welfare". Userwww.service.emory.edu. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ Hasin, Deborah. "Lesbian, gay, bisexual individuals risk psychiatric disorders from discriminatory policies". Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ Mustanski, Brian (22 March 2010). "New study suggests bans on gay marriage hurt mental health of LGB people". Psychology Today. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ^ Raifman, Julia; Moscoe, Ellen; Austin, S. Bryn; McConnell, Margaret (2017). "Difference-in-Differences Analysis of the Association Between State Same-Sex Marriage Policies and Adolescent Suicide Attempts". JAMA Pediatrics. 171 (4): 350–356. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4529. PMC 5848493. PMID 28241285.

- ^ "Same-Sex Marriage Legalization Linked to Reduction in Suicide Attempts Among High School Students". Johns Hopkins University. 20 February 2017. Archived from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Laurie, Timothy (3 June 2015). "Bigotry or biology: the hard choice for an opponent of marriage equality". The Drum. Archived from the original on 4 June 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ Blankenhorn, David (19 September 2008). "Protecting marriage to protect children". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ "See discussion of prenuptial and postmarital agreements at Findlaw". Family.findlaw.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Pawelski JG, Perrin EC, Foy JM, et al. (July 2006). "The effects of marriage, civil union, and domestic partnership laws on the health and well-being of children". Pediatrics. 118 (1): 349–64. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1279. PMID 16818585. S2CID 219194821.

- ^ Lamb, Michael. "Expert Affidavit for U.S. District Court (D. Mass. 2009)" (PDF). Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Pediatricians: Gay Marriage Good for Kids' Health". news.discovery.com. 22 March 2013. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ "Elizabeth Short, Damien W. Riggs, Amaryll Perlesz, Rhonda Brown, Graeme Kane: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Parented Families – A Literature Review prepared for The Australian Psychological Society" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ "Brief of the American Psychological Association, The California Psychological Association, The American Psychiatric Association, and The American Association of Marriage and Family Therapy as Amici Curiae in Support of Plaintiff-Appellees" (PDF). United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ Herek, GM (September 2006). "Legal recognition of same-sex relationships in the United States: a social science perspective" (PDF). The American Psychologist. 61 (6): 607–21. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.61.6.607. PMID 16953748. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2010.

- ^ Biblarz, Timothy J.; Stacey, Judith (February 2010). "How Does the Gender of Parents Matter?" (PDF). Journal of Marriage and Family. 72 (1): 3–22. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.593.4963. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00678.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2013.

- ^ "Brief presented to the Legislative House of Commons Committee on Bill C38 by the Canadian Psychological Association – 2 June 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ Goldberg, Abbie E. (February 2023). "LGBTQ-parent families: Diversity, intersectionality, and social context". Current Opinion in Psychology. 49: 101517. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101517. PMID 36502588. S2CID 253665001.

- ^ Leal, Daniela; Gato, Jorge; Coimbra, Susana; Freitas, Daniela; Tasker, Fiona (December 2021). "Social Support in the Transition to Parenthood Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Persons: A Systematic Review". Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 18 (4): 1165–1179. doi:10.1007/s13178-020-00517-y. hdl:10216/132451.

- ^ Bockting, Walter, Autumn Benner, and Eli Coleman. "Gay and Bisexual Identity Development Among Female-to-Male Transsexuals in North America: Emergence of a Transgender Sexuality." Archives of Sexual Behavior 38.5 (October 2009): 688–701. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. 29 September 2009

- ^ "Austria gets first same-sex marriage". 365gay.com. 5 July 2006. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- ^ "Sweden ends forced sterilization of trans". gaystarnews.com. 11 January 2013. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ Deborah, Anthony (Spring 2012). "CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE: TRANSSEXUAL MARRIAGE AND THE DISCONNECT BETWEEN SEX AND LEGAL SEX". Texas Journal of Women & the Law. 21 (2).

- ^ Schwartz, John (18 September 2009). "U.S. Defends Marriage Law". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ^ "Movement Advancement Project | Equality Maps". www.lgbtmap.org. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ Matthew S. Coleman (16 September 2015). "Obergefell v. Hodges". Einhorn Harris. Archived from the original on 24 December 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ Leff, Lisa (4 December 2008). "Poll: Calif. gay marriage ban driven by religion". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. archived here.

- ^ For ease of comparison, only 'yes' and 'no' responses are counted. For old polling data, support figures have been adjusted upward @1%/year.

- ^ Newport, Frank (20 May 2011). "For First Time, Majority of Americans Favor Legal Gay Marriage". Gallup. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ "Public Opinion: Nationally". australianmarriageequality.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ "Gay Life in Estonia". globalgayz.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ Jowit, Juliette (12 June 2012). "Gay marriage gets ministerial approval". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ "Most Irish people support gay marriage, poll says". PinkNews. 24 February 2011. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ a b "How people in 24 countries view same-sex marriage". Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ "What the world's young people think and feel" (PDF).

- ^ "Who supports equal rights for same-sex couples?". Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- ^ "Age is decisive factor when it comes to supporting same-sex marriage: LAPOP". Vanderbilt University. 2 June 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Attitudes towards LGBTIQ+ people in the Western Balkans" (PDF). ERA – LGBTI Equal Rights Association for the Western Balkans and Turke. June 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2024.

- ^ "Un 70% d'andorrans aprova el matrimoni homosexual". Diari d'Andorra (in Catalan). 7 July 2013. Archived from the original on 27 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Cultura polítical de la democracia en la República Dominicana y en las Américas, 2016/17" (PDF). Vanderbilt University (in Spanish). 13 November 2017. p. 132. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x LGBT+ PRIDE 2024 (PDF). Ipsos. 1 May 2024. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Gubbala, Sneha; Poushter, Jacob; Huang, Christine (27 November 2023). "How people in 24 countries view same-sex marriage". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 13 December 2024. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe" (PDF). Pew. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Religious belief and national belonging in Central and Eastern Europe - Appendix A: Methodology". Pew Research Center. 10 May 2017. Archived from the original on 28 November 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ "Bevolking Aruba pro geregistreerd partnerschap zelfde geslacht". Antiliaans Dagblad (in Dutch). 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 10 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "Discrimination in the European Union". TNS. European Commission. Archived from the original on 3 December 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2024. The question was whether same-sex marriage should be allowed throughout Europe.

- ^ a b c d e "Barómetro de las Américas: Actualidad – 2 de junio de 2015" (PDF). Vanderbilt University. 2 July 2015.

- ^ "63% está de acuerdo con la creación de una AFP Estatal que compita con las actuales AFPs privadas" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 10 June 2024. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ a b LGBT+ PRIDE 2021 GLOBAL SURVEY (PDF). Ipsos. 16 June 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2024. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Unknown[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Encuesta: Un 63,1% de los cubanos quiere matrimonio igualitario en la Isla". Diario de Cuba (in Spanish). 18 July 2019. Archived from the original on 21 July 2019.

- ^ Guzman, Samuel (5 February 2018). "Encuesta de CDN sobre matrimonio homosexual en RD recibe más de 300 mil votos - CDN - El Canal de Noticias de los Dominicanos" [CDN survey on homosexual marriage in DR receives more than 300 thousand votes] (in Spanish).

- ^ America's Barometer Topical Brief #034, Disapproval of Same-Sex Marriage in Ecuador: A Clash of Generations?, 23 July 2019. Counting ratings 1–3 as 'disapprove', 8–10 as 'approve', and 4–7 as neither.

- ^ "Partido de Bukele se "consolida" en preferencias electorales en El Salvador". 21 January 2021.

- ^ "წინარწმენიდან თანასწორობამდე (From Prejudice to Equality), part 2" (PDF). WISG. 2022.

- ^ "Más del 70% de los hondureños rechaza el matrimonio homosexual". Diario La Prensa (in Spanish). 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Litlar breytingar á viðhorfi til giftinga samkynhneigðra" (PDF) (in Icelandic). Gallup. September 2006.

- ^ Staff (13 February 2023). "64% favor recognizing same-sex marriage in Japan: Kyodo poll". Kyodo News. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ Isoda, Kazuaki (21 February 2023). "Survey: 72% of voters in favor of legalizing gay marriages". The Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Vogt, Desiree (March 2021). "Rückhalt für gleichgeschlechtliche Paare". Liechtensteiner Vaterland (in German).

- ^ "Sondaj: chișinăuienii au devenit mai toleranți față de comunitatea LGBT". Radio Europa Liberă Moldova (in Romanian). 18 May 2022.

- ^ "Most Mozambicans against homosexual violence, study finds". MambaOnline - Gay South Africa online. 4 June 2018., (full report)

- ^ a b c d e LGBT+ PRIDE 2023 GLOBAL SURVEY (PDF). Ipsos. 1 June 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 November 2024. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ "First Quarter 2018 Social Weather Survey: 61% of Pinoys oppose, and 22% support, a law that will allow the civil union of two men or two women". 29 June 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ "(Nie)dzielące związki: Polki i Polacy o prawach par jednopłciowych". More in Common. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ Mikołajczyk, Marek (24 April 2024). "Tak dla związków partnerskich, nie dla adopcji [SONDAŻ DGP]". Dziennik Gazeta Prawna. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ "Отношение к сексменьшинствам" (in Russian). ФОМ. June 2019.

- ^ "Polovici slovenských občanov neprekážajú registrované partnerstvá pre páry rovnakého pohlavia". 27 March 2024.

- ^ Strong, Matthew (19 May 2023). "Support for gay marriage surges in Taiwan 4 years after legalization". Taiwan News. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ "Соціологічне дослідження до Дня Незалежності: УЯВЛЕННЯ ПРО ПАТРІОТИЗМ ТА МАЙБУТНЄ УКРАЇНИ (16-20 серпня 2023) Назад до списку" (in Ukrainian). 24 August 2023. Archived from the original on 13 December 2024.

- ^ Simons, Ned (4 February 2023). "It's Ten Years Since MPs Voted For Gay Marriage, But Is There A 'Backlash'?". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 13 December 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Opinión sobre el matrimonio igualitario" [Opinion on equal marriage]. LatinoBarómetro. 10 June 2024.

- ^ Antolínez, Héctor (2 March 2023). "Encuesta refleja que mayoría de venezolanos apoya igualdad de derechos para la población LGBTIQ". Crónica Uno (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 December 2024. Retrieved 13 December 2024.

Bibliography

- Boswell, John (1995). The Marriage of Likeness: Same-sex Unions in Pre-modern Europe. New York: Simon Harper and Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-255508-1.

- Boswell, John (1994). Same-sex Unions in Premodern Europe. New York: Villard Books. ISBN 978-0-679-43228-9.

- Brownson, James V. (2013). Bible, Gender, Sexuality: Reforming the Church's Debate on Same-Sex Relationships. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-6863-3.

- Calò, Emanuele (2009). Matrimonio à la carte — Matrimoni, convivenze registrate e divorzi dopo l'intervento comunitario. Milano: Giuffrè.

- Caramagno, Thomas C. (2002). Irreconcilable Differences? Intellectual Stalemate in the Gay Rights Debate. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-97721-4.

- Cere, Daniel (2004). Divorcing Marriage: Unveiling the Dangers in Canada's New Social Experiment. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2895-6.