SS Dronning Maud (1925)

68°41.917′N 017°26.367′E / 68.698617°N 17.439450°E

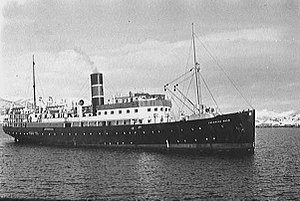

Dronning Maud in 1936

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Dronning Maud |

| Namesake | Queen Maud of Norway |

| Owner | Det Nordenfjeldske Dampskipsselskap[1] |

| Port of registry | Trondheim[1] |

| Route | Hurtigruten |

| Ordered | June 1924[2] |

| Builder | Fredrikstad Mekaniske Verksted[3] |

| Cost | 2,000,000 kr[2] |

| Yard number | 246[3] |

| Launched | 8 May 1925[3] |

| Christened | 30 June 1925[2] |

| Commissioned | 3 July 1925[2] |

| Maiden voyage | 30 June 1925[2] |

| In service | 13 July 1925[1] |

| Out of service | 1 May 1940[1] |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Sunk by German aircraft[1] |

| General characteristics | |

| Type |

|

| Tonnage | 1,489 gross register tons (GRT)[1] |

| Length | 235 ft (71.63 m)[2] |

| Beam | 11.5 ft (3.51 m)[3] |

| Propulsion | 1,500 hp triple expansion steam engine[2] |

| Speed |

|

| Capacity | 400 passengers (1925)[1] |

| Armament | |

SS Dronning Maud was a 1,489 ton steel-hulled steamship built in 1925 by the Norwegian shipyard Fredrikstad Mekaniske Verksted in Fredrikstad.[4] Dronning Maud was ordered by the Trondheim-based company Det Nordenfjeldske Dampskipsselskap for the passenger and freight service Hurtigruten along the coast of Norway. She served this route as the company flagship until she was sunk under controversial circumstances during the 1940 Norwegian Campaign.

Before the Second World War

Building and commissioning

Dronning Maud was ordered from Fredrikstad Mekaniske Verksted shortly after the loss of Det Nordenfjeldske Dampskipsselskap's Haakon Jarl.[2] Haakon Jarl had suffered a collision with fellow Nordenfjeldske ship Kong Harald in the Vestfjord on 17 June 1924, sinking with the loss of 12 passengers and seven crew members.[6] The building order of Dronning Maud made her the first new ship to join the Hurtigruten route since Finmarken in 1912.[2] After her 8 May 1925 launch she had her first test run in the Oslofjord on 30 June 1925 and was formally handed over to Nordenfjeldske on 3 July. Nordenfjeldske immediately sent her northwards to Trondheim from where she joined the northbound Hurtigruten service, sailing from Brattøra at 12:00 on 13 July.[2]

Characteristics

With the construction of Dronning Maud a new concept was introduced to the Hurtigruten ships, with the First Class section moved forward to amidships and the Second Class removed altogether in order to make room for a greatly improved Third Class in the aft section. The salons and cabins in the Third Class area on board Dronning Maud were described at the time as both "light and practical".[2] Her outer appearance was characterized by long, clean lines, a large superstructure and a long continuous promenade deck.[2] She was considered a very seaworthy vessel and in 1931 became the first Hurtigruten ship to be equipped with the new safety feature of wireless telegraphy.[2] By 1936 all the Hurtigruten ships had been equipped with the new technology.[7]

Hurtigruten service

After she entered service with Nordenfjeldske Dronning Maud sailed with passengers and freight along the coast of Norway. During her regular coastal service in the 1920s and 1930s the ship repeatedly had to come to the assistance of ships in difficulties. In 1926 she assisted the 556 ton steamer Pallas after the latter had run aground off Grønøy[8] and in 1927 she helped a British trawler after it had run aground in the sound Magerøysund in Finnmark.[1] Dronning Maud herself had an accident when she ran aground south of Florø in October 1929.[1]

Second World War

At the outbreak of the Second World War Norway declared herself neutral and the Hurtigruten service continued as normal in the first months of the war.

Johann Schulte

During this period Dronning Maud was involved in a dramatic incident when on 1 January 1940 the 5,334 ton[9] German merchantman Johann Schulte shipwrecked at Buholmråsa after losing her propeller. Coming to the iron ore-laden[10] Johann Schulte's rescue through a north-westerly gale and snow Captain Edward M. Grundt brought his vessel close enough to the German ship so that a line could be thrown on board and used to drag the shipwrecked people to safety. In all Dronning Maud and her crew saved all 36 German sailors and two Norwegian pilots from the sinking ship.[2][11][12] After everyone on board had been pulled to safety the German ship hit a reef near Bessaker and was crushed.[10] During the rescue operation, carried out at night in pitch black conditions, some 100 passengers and 45 crew were on board the Hurtigruten ship.[10] The rescued Germans were set ashore in Rørvik while the two pilots remained on board as Dronning Maud continued northwards.[11] Johann Schulte rescue has been described as one of the most incredible ever accomplished on the Norwegian coast,[13] and resulted in congratulatory telegrams to the ship when it reached Svolvær and later monetary gifts to the crew.[10] In the 1960s Captain Grundt received a gold medal from the German rescue society and a diploma from the Norwegian counterpart for his efforts.[10]

Norwegian Campaign

Troopship duties

When the Germans invaded Norway on 9 April 1940 Dronning Maud was northbound off Sandnessjøen in Nordland and continued northwards to her end port of Kirkenes in Finnmark. After arriving in Kirkenes she was requisitioned by the Norwegian government as a troopship.[2][14]

Dronning Maud's first troopship assignment was to take part in the transport of Battalion I of Infantry Regiment 12 (I/IR12) from Sør-Varanger to the Tromsø-Narvik area. Escorted by the British heavy cruiser Berwick and the destroyer Inglefield, Dronning Maud and two smaller vessels from Vesteraalens Dampskibsselskab (the 874 ton[15] SS Kong Haakon and Hestmanden) disembarked most of the Norwegian infantry battalion at Sjøvegan in Troms on 16 April 1940. The remainder of the battalion was transported on the fellow Nordenfjeldske Dampskibsselskab steamer Prins Olav a few days later.[16][17][18] The next day, 17 April, Dronning Maud and Kong Haakon were escorted northwards to Sagfjorden by the Norwegian the off-shore patrol vessel Heimdal.[18]

The second troopship mission Dronning Maud carried out was the transport of one infantry company, the battalion's staff, the communications platoon and one heavy machine gun platoon of the Alta Battalion from Alta in Finnmark to areas closer to the front line in Troms.[19] The rest of the battalion was transported on the Kong Haakon and the 858 ton[20] cargo ship Senja.[5] The three troopships were originally meant to be escorted by the off-shore patrol vessel Fridtjof Nansen but this order was changed and the ships were instead to sail without escort.[19] The three ships set off from Alta singly; Kong Haakon at 21:00 on 19 April, Dronning Maud at 22:00 the same day, and Senja at 04:00 on 20 April. Each of the three ships carried a heavy machine gun platoon for anti-aircraft defence, Senja had two platoons as she was transporting the battalion's horses.[5] Dronning Maud and Kong Haakon arrived almost simultaneous at Tromsø at 09:00 on 20 April, then continuing southwards after a short conference with the naval authorities in Tromsø. Dronning Maud that time sailed at 10:00, while Kong Haakon followed at 11:00, both ships still without escort. As Dronning Maud reached the island of Dyrøy she was stopped by the patrol boat Thorodd and told to wait for Kong Haakon. When Kong Haakon reached Dyrøy the two Hurtigruten ship continued to Sjøvegan under escort by Thorodd, arriving at 17:30 on 20 April and disembarking the troops.[5]

After the completion of her troop transporting missions the Norwegian authorities decided to use Dronning Maud to transport the 6th Landvern Medical Company (Template:Lang-no) from Sørreisa to Foldvik in Gratangen.[18] The company she was tasked with transporting consisted of 119 medics, along with eight horses and three trucks.[13] In preparation for the voyage to Foldvik Dronning Maud had one 3-metre by 3-metre (9.8 ft by 9.8 ft) Red Cross flag stretched out over her bridge deck and flew two more Red Cross flags in her masts.[18]

Final voyage

Dronning Maud set off from Sørreisa at around 11:30 on 1 May 1940, arriving at Foldvik three to four hours later in calm seas and sunshine. As the ship was about to dock with the small wharf on her port side two[18] or three[2] aircraft of the German Lehrgeschwader 1[21] made a low-level attack with bombs and machine gun fire[2] on the Norwegian steamer. Seven bombs were dropped from the aircraft, with two being direct hits, one between the funnel and the bridge, the other just aft of the fore cargo hatch. The first bomb entered the engine room and blew out the ship's sides and the second exploded in the bottom of the hull. The first bomb killed everyone in the refrigeration room, four men and three women.[18] As the crew and passengers tried to abandon ship only one or two boats could be lowered into the water due to the fire that had broken out on board. The fire also threatened to destroy the wooden wharf at Foldvik, until a local fishing boat managed to pull the burning ship some distance away from shore.[18] Dronning Maud drifted a short distance, then ran aground, burned and sank listing to port.[14]

Following their attack on Dronning Maud the German aircraft proceeded to bomb nearby Gratangen, destroying several houses and killing two civilians.[22]

After the attack the wounded survivors were given first aid by the crew of the 378 ton[23] hospital ship MS Elieser. In the evening the British destroyer HMS Cossack brought the most severely wounded to hospital in Harstad while Elieser transported those less critically wounded to Salangsverket.[18]

Nine medics lost their lives during the attack, while a tenth later died in a hospital near Harstad. Of the ship's crew eight died and all the materiel on board was lost when Dronning Maud went down.[18][24] Thirty-one medics and crew members were injured in the sinking of the ship,[25] two of them severely.[22]

The wreck of Dronning Maud remains where she sank, a short distance off the wharf at Foldvik in Gratangen. The ship is still upright at around 26 to 35 metres (85 to 115 ft) depth, at coordinates 68°41.917′N 017°26.367′E / 68.698617°N 17.439450°E.[4]

Reactions to the sinking

The sinking of Dronning Maud, an unarmed ship flying Red Cross flags and carrying medical personnel, brought a great amount of anger and criticism directed against the Germans. From the Norwegian perspective Dronning Maud had been a hospital ship and under the protection of the Geneva Conventions. The Germans retorted by pointing out that Dronning Maud had not been fully marked as a hospital ship, as she had retained her black hull instead of it being painted white with a horizontal green stripe.[18]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lawson, Siri Holm. "D/S Dronning Maud". Warsailors.com. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Bakka 1993: 52

- ^ a b c d "Dronning Maud (5606285)". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ a b c Andresen, Dag-Jostein (2 April 2004). "D/S Dronning Maud". Vrakdykking i Nord- og Midt-Norge (in Norwegian). p. 5. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d Ramberg 1996: 102

- ^ Bakka 1993: 45–46

- ^ Fauske, Henrik. "Skipstrafikk". Svolvær Historical Society (in Norwegian). Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ Lawson, Siri Holm. "D/S Pallas". Warsailors.com. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ "Johann Schulte (1150573)". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Andresen, Dag-Jostein (2 April 2004). "D/S Dronning Maud". Vrakdykking i Nord- og Midt-Norge (in Norwegian). p. 3. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ a b Andresen, Dag-Jostein (2 April 2004). "D/S Dronning Maud". Vrakdykking i Nord- og Midt-Norge (in Norwegian). p. 2. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ "World War: Conquering Heroes". Time. 15 January 1940. p. 1. Archived from the original on 14 October 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ^ a b "Dronning Maud". Sjømennenes minnehall i Stavern (in Norwegian). Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ a b Abelsen 1986: 299

- ^ Lawson, Siri Holm. "D/S Kong Haakon". Warsailors.com. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ Berg 1991: 43–44

- ^ Kindell, Don. "Naval Events, April 1940, Part 2 of 4 Monday 8th – Sunday 14th". Naval-History.net. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Andresen, Dag-Jostein (2 April 2004). "D/S Dronning Maud". Vrakdykking i Nord- og Midt-Norge (in Norwegian). p. 4. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ a b Ramberg 1996: 101

- ^ Lawson, Siri Holm. "M/S Senja". Warsailors.com. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ de Zeng 2007: 359

- ^ a b Hafsten 1991: 43

- ^ Lawson, Siri Holm. "M/S Elieser". Warsailors.com. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ Steen 1958, p. 233

- ^ Voksø 1994: 36

Bibliography

- Abelsen, Frank (1986). Norwegian naval ships 1939–1945 (in Norwegian and English). Oslo: Sem & Stenersen AS. ISBN 82-7046-050-8.

- Bakka, Dag Jr. (1993). Skipene som bandt kysten sammen – Hurtigruten gjennom 100 år (in Norwegian). Bergen: Rhema Forlag.

- Berg, Johan Helge; Olav Vollan (1991). I Trønderbataljonens fotspor – 50 år etter: Gratangen 1940 (in Norwegian) (2nd ed.). Trondheim: Lyngs Bokhandel A/s. ISBN 82-992129-0-1.

- de Zeng, Henry L.; Douglas G. Stanket; Eddie J. Creek (2007). Bomber Units of the Luftwaffe 1933–1945; A Reference Source, Volume 2. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-1-903223-87-1.

- Hafsten, Bjørn; Ulf Larsstuvold; Bjørn Olsen; Sten Stenersen (1991). Flyalarm – luftkrigen over Norge 1939–1945 (in Norwegian) (1st ed.). Oslo: Sem og Stenersen AS. ISBN 82-7046-058-3.

- Ramberg, S. E. L.; Trygve Andersen; Arvid Petterson (1996). Alta bataljons historie 1898–1995 (in Norwegian). Alta: Alta Battalion. ISBN 82-90579-14-4.

- Steen, Erik Anker (1958). Norge sjøkrig 1940–1945 – Sjøforsvarets kamper og virke i Nord-Norge 1940 (in Norwegian). Vol. 4. Oslo: Forsvarets Krigshistoriske Avdeling/Gyldendal Norsk Forlag.

- Voksø, Per (1994). Krigens Dagbok – Norge 1940–1945 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Forlaget Det Beste. ISBN 82-7010-245-8.